Plutino

In astronomy, the plutinos are a dynamical group of trans-Neptunian objects that orbit in 2:3 mean-motion resonance with Neptune. This means that for every two orbits a plutino makes, Neptune orbits three times. The dwarf planet Pluto is the largest member as well as the namesake of this group. Plutinos are named after mythological creatures associated with the underworld.

|

Plutinos form the inner part of the Kuiper belt and represent about a quarter of the known Kuiper belt objects. They are also the most populous known class of resonant trans-Neptunian objects (also see adjunct box with hierarchical listing). Aside from Pluto itself, the first plutino, (385185) 1993 RO, was discovered on September 16, 1993.

Orbits

Origin

It is thought that the objects that are currently in mean orbital resonances with Neptune initially followed a variety of independent heliocentric paths. As Neptune migrated outward early in the Solar System's history (see origins of the Kuiper belt), the bodies it approached would have been scattered; during this process, some of them would have been captured into resonances.[1] The 3:2 resonance is a low-order resonance and is thus the strongest and most stable among all resonances.[2] This is the primary reason it has a larger population than the other Neptunian resonances encountered in the Kuiper Belt. The cloud of low-inclination bodies beyond 40 AU is the cubewano family, while bodies with higher eccentricities (0.05 to 0.34) and semimajor axes close to the 3:2 Neptune resonance are primarily plutinos.[3]

Orbital characteristics

While the majority of plutinos have relatively low orbital inclinations, a significant fraction of these objects follow orbits similar to that of Pluto, with inclinations in the 10–25° range and eccentricities around 0.2–0.25; such orbits result in many of these objects having perihelia close to or even inside Neptune's orbit, while simultaneously having aphelia that bring them close to the main Kuiper belt's outer edge (where objects in a 1:2 resonance with Neptune, the Twotinos, are found).

The orbital periods of plutinos cluster around 247.3 years (1.5 × Neptune's orbital period), varying by at most a few years from this value.

Unusual plutinos include:

- 2005 TV189, which follows the most highly inclined orbit (34.5°)

- (15875) 1996 TP66, which has the most elliptical orbit (its eccentricity is 0.33), with the perihelion halfway between Uranus and Neptune

- (470308) 2007 JH43 following a quasi-circular orbit

- 2002 VX130 lying almost perfectly on the ecliptic (inclination less than 1.5°)

See also the comparison with the distribution of the cubewanos.

Long-term stability

Pluto's influence on the other plutinos has historically been neglected due to its relatively small mass. However, the resonance width (the range of semi-axes compatible with the resonance) is very narrow and only a few times larger than Pluto's Hill sphere (gravitational influence). Consequently, depending on the original eccentricity, some plutinos will eventually be driven out of the resonance by interactions with Pluto.[4] Numerical simulations suggest that the orbits of plutinos with an eccentricity 10%–30% smaller or larger than that of Pluto are not stable over Ga timescales.[5]

Orbital diagrams

The motions of Orcus and Pluto in a rotating frame with a period equal to Neptune's orbital period (holding Neptune stationary.)

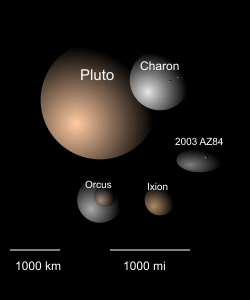

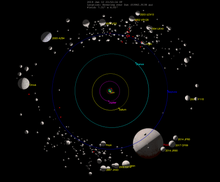

The motions of Orcus and Pluto in a rotating frame with a period equal to Neptune's orbital period (holding Neptune stationary.) Orbits and sizes of the larger plutinos (and the reference non-plutino 2002 KX14). Orbital eccentricity is represented by segments extending horizontally from perihelion to aphelion; inclination is shown on the vertical axis.

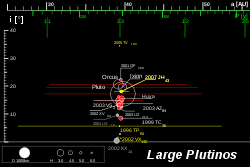

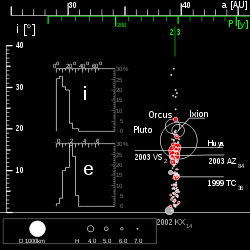

Orbits and sizes of the larger plutinos (and the reference non-plutino 2002 KX14). Orbital eccentricity is represented by segments extending horizontally from perihelion to aphelion; inclination is shown on the vertical axis. The distribution of plutinos (and the reference non-plutino 2002 KX14). Small inserts show histograms for the distributions of orbital inclination and eccentricity.

The distribution of plutinos (and the reference non-plutino 2002 KX14). Small inserts show histograms for the distributions of orbital inclination and eccentricity.

Brightest objects

The plutinos brighter than HV=6 include:

| Object | a (AU) | q (AU) | i (°) | H | Diameter (km) | Mass (1020 kg) | Albedo | V−R | Discovery year | Discoverer | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 134340 Pluto | 39.3 | 29.7 | 17.1 | −0.7 | 2322 | 130 | 0.49–0.66 | 1930 | Clyde Tombaugh | JPL | |

| 90482 Orcus | 39.2 | 30.3 | 20.6 | 2.31±0.03 | 917±25 | 6.32±0.05 | 0.28±0.06 | 0.37 | 2004 | M. Brown, C. Trujillo, D. Rabinowitz | JPL |

| (208996) 2003 AZ84 | 39.4 | 32.3 | 13.6 | 3.74±0.08 | 727.0+61.9 −66.5 | ≈ 3 | 0.107+0.023 −0.016 | 0.38±0.04 | 2003 | M. Brown, C. Trujillo | JPL |

| 28978 Ixion | 39.7 | 30.1 | 19.6 | 3.828±0.039 | 617+19 −20 | ≈ 3 | 0.141±0.011 | 0.61 | 2001 | Deep Ecliptic Survey | JPL |

| 2017 OF69 | 39.5 | 31.3 | 13.6 | 4.091±0.12 | ≈ 380–680 | ? | ? | ? | 2017 | D. J. Tholen, S. S. Sheppard, C. Trujillo | JPL |

| (84922) 2003 VS2 | 39.3 | 36.4 | 14.8 | 4.1±0.38 | 523.0+35.1 −34.4 | ≈ 1.5 | 0.147+0.063 −0.043 | 0.59±0.02 | 2003 | NEAT | JPL |

| (455502) 2003 UZ413 | 39.2 | 30.4 | 12.0 | 4.38±0.05 | ≈ 600 | ≈ 2 | ? | 0.46±0.06 | 2001 | M. Brown, C. Trujillo, D. Rabinowitz | JPL |

| 2014 JR80 | 39.5 | 36.0 | 15.4 | 4.9 | ≈ 240–670 | ? | ? | ? | 2014 | Pan-STARRS | JPL |

| 2014 JP80 | 39.5 | 36.7 | 19.4 | 4.9 | ≈ 240–670 | ? | ? | ? | 2014 | Pan-STARRS | JPL |

| 38628 Huya | 39.4 | 28.5 | 15.5 | 5.04±0.03 | 406±16 | ≈ 0.5 | 0.083±0.004 | 0.57±0.09 | 2000 | Ignacio Ferrin | JPL |

| (469987) 2006 HJ123 | 39.3 | 27.4 | 12.0 | 5.32±0.66 | 283.1+142.3 −110.8 | ≈ 0.012 | 0.136+0.308 −0.089 | 2006 | Marc W. Buie | JPL | |

| 2002 XV93 | 39.3 | 34.5 | 13.3 | 5.42±0.46 | 549.2+21.7 −23.0 | ≈ 1.7 | 0.040+0.020 −0.015 | 0.37±0.02 | 2001 | M.W.Buie | JPL |

| (469372) 2001 QF298 | 39.3 | 34.9 | 22.4 | 5.43±0.07 | 408.2+40.2 −44.9 | ≈ 0.7 | 0.071+0.020 −0.014 | 0.39±0.06 | 2001 | Marc W. Buie | JPL |

| 47171 Lempo | 39.3 | 30.6 | 8.4 | 5.41±0.10 | 393.1+25.2 −26.8 (triple) | 0.1275±0.0006 | 0.079+0.013 −0.011 | 0.70±0.03 | 1999 | E. P. Rubenstein, L.-G. Strolger | JPL |

| (307463) 2002 VU130 | 39.3 | 31.2 | 14.0 | 5.47±0.83 | 252.9+33.6 −31.3 | ≈ 0.16 | 0.179+0.202 −0.103 | 2002 | Marc W. Buie | JPL | |

| (84719) 2002 VR128 | 39.3 | 28.9 | 14.0 | 5.58±0.37 | 448.5+42.1 −43.2 | ≈ 1 | 0.052+0.027 −0.018 | 0.60±0.02 | 2002 | NEAT | JPL |

| (55638) 2002 VE95 | 39.4 | 30.4 | 16.3 | 5.70±0.06 | 249.8+13.5 −13.1 | ≈ 0.15 | 0.149+0.019 −0.016 | 0.72±0.05 | 2002 | NEAT | JPL |

References

- Malhotra, Renu (1995). "The Origin of Pluto's Orbit: Implications for the Solar System Beyond Neptune". Astronomical Journal. 110: 420. arXiv:astro-ph/9504036. Bibcode:1995AJ....110..420M. doi:10.1086/117532.

- Almeida, A.J.C; Peixinho, N.; Correia, A.C.M. (December 2009). "Neptune Trojans & Plutinos: Colors, sizes, dynamics, & their possible collisions". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 508 (2): 1021–1030. arXiv:0910.0865. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200911943. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- Lewis, John S. (2004). Physics & Chemistry of the Solar System. Centaurs & Trans-Neptunian Objects. Academic Press. pp. 409–412. ISBN 012446744X. Retrieved 2019-07-21.

- Wan, X.-S; Huang, T.-Y. (2001). "The orbit evolution of 32 plutinos over 100 million year". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 368 (2): 700–705. Bibcode:2001A&A...368..700W. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20010056.

- Yu, Qingjuan; Tremaine, Scott (1999). "The Dynamics of Plutinos". Astronomical Journal. 118 (4): 1873–1881. arXiv:astro-ph/9904424. Bibcode:1999AJ....118.1873Y. doi:10.1086/301045.

- D.Jewitt, A.Delsanti The Solar System Beyond The Planets in Solar System Update : Topical and Timely Reviews in Solar System Sciences , Springer-Praxis Ed., ISBN 3-540-26056-0 (2006). Preprint of the article (pdf)

- Bernstein G.M., Trilling D.E., Allen R.L., Brown K.E, Holman M., Malhotra R. The size Distribution of transneptunian bodies. The Astronomical Journal, 128, 1364–1390. preprint on arXiv

- Minor Planet Center Orbit database (MPCORB) as of 2008-10-05.

- Minor Planet Circular 2008-S05 (October 2008) Distant Minor planets was used for orbit classification.