Dramatic structure

Dramatic structure is the structure of a dramatic work such as a play or film. Many scholars have analyzed dramatic structure, beginning with Aristotle in his Poetics (c. 335 BCE). This article looks at Aristotle's analysis of the Greek tragedy and on Gustav Freytag's analysis of ancient Greek and Shakespearean drama. Northrop Frye also offers a dramatic structure for the analysis of narratives: an inverted U-shaped plot structure for tragedies and a U-shaped plot structure for comedies.[1]

History

In his Poetics, the Greek philosopher Aristotle put forth the idea the play should imitate a single whole action. "A whole is what has a beginning and middle and end" (1450b27).[2] He split the play into two parts: complication and unravelling.

The Roman drama critic Horace advocated a 5-act structure in his Ars Poetica: "Neue minor neu sit quinto productior actu fabula" (lines 189–190) ("A play should not be shorter or longer than five acts").

The fourth-century Roman grammarian Aelius Donatus defined the play as a three part structure, the protasis, epitasis, and catastrophe.

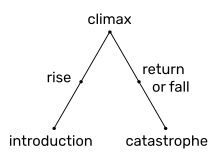

In 1863, around the time that playwrights like Henrik Ibsen were abandoning the 5-act structure and experimenting with 3 and 4-act plays, the German playwright and novelist Gustav Freytag wrote Die Technik des Dramas, a definitive study of the 5-act dramatic structure, in which he laid out what has come to be known as Freytag's pyramid.[3] Under Freytag's pyramid, the plot of a story consists of five parts:[4][5]

- Exposition (originally called introduction)

- Rising action (rise)

- Climax

- Falling action (return or fall)

- Catastrophe, denouement, resolution, or revelation

Aristotle's analysis

Many structural principles still in use by modern storytellers were explained by Aristotle in his Poetics. In the part that still exists, he mostly analyzed the tragedy. A part analyzing the comedy is believed to have existed but is now lost.

Aristotle stated that the tragedy should imitate a whole action, which means that the events follow each other by probability or necessity, and that the causal chain has a beginning and an end.[6] There is a knot, a central problem that the protagonist must face. The play has two parts: complication and unravelling.[7] During complication, the protagonist finds trouble as the knot is revealed or tied; during unraveling, the knot is resolved.[8]

Two types of scenes are of special interest: the reversal, which throws the action in a new direction, and the recognition, meaning the protagonist has an important revelation.[9] Reversals should happen as a necessary and probable cause of what happened before, which implies that turning points need to be properly set up.[10]

Complications should arise from a flaw in the protagonist. In the tragedy, this flaw will be his undoing.[11]

Freytag's analysis

Freytag derives his five-part model from the conflict of man against man, the hero and his adversary. The action of the drama and the grouping of characters is therefore in two parts: the hero's own deeds and those of his antagonist, which Freytag variously describes as "play and counter-play" ("Spiel und Gegenspiel" in the original)[13] or "rising and sinking". The greater the rise, the greater the fall of the vanquished hero. These two contrasting parts of the drama must be united by a climax, to which the action rises and from which the action falls away. Either the play or the counter-play can maintain dominance over the first part or the second part; either is allowed. Freytag is indifferent as to which of the contending parties justice favors; in both groups, good and evil, power and weakness, are mingled.[14]

A drama is then divided into five parts, or acts, which some refer to as a dramatic arc: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and catastrophe. Freytag extends the five parts with three moments or crises: the exciting force, the tragic force, and the force of the final suspense. The exciting force leads to the rising action, the tragic force leads to the falling action, and the force of the final suspense leads to the catastrophe. Freytag considers the exciting force to be necessary but the tragic force and the force of the final suspense are optional. Together, they make the eight component parts of the drama.[15] Freytag's Pyramid can help writers organize their thoughts and ideas when describing the main problem of the drama, the rising action, the climax and the falling action.

Although Freytag's analysis of dramatic structure is based on five-act plays, it can be applied (sometimes in a modified manner) to short stories and novels as well, making dramatic structure a literary element.

Exposition

The setting is fixed in a particular place and time, the mood is set, and characters are introduced. A backstory may be alluded to. Exposition can be conveyed through dialogues, flashbacks, characters' asides, background details, in-universe media, or the narrator telling a back-story.[16]

Rising action

An exciting force or inciting event begins immediately after the exposition (introduction), building the rising action in one or several stages toward the point of greatest interest. These events are generally the most important parts of the story since the entire plot depends on them to set up the climax and ultimately the satisfactory resolution of the story itself.[17]

Climax

The climax is the turning point, which changes the protagonist's fate. If things were going well for the protagonist, the plot will turn against them, often revealing the protagonist's hidden weaknesses.[18] If the story is a comedy, the opposite state of affairs will ensue, with things going from bad to good for the protagonist, often requiring the protagonist to draw on hidden inner strengths.

Falling action

During the falling action, the hostility of the counter-party beats upon the soul of the hero. Freytag lays out two rules for this stage: the number of characters be limited as much as possible, and the number of scenes through which the hero falls should be fewer than in the rising movement. The falling action may contain a moment of final suspense: Although the catastrophe must be foreshadowed so as not to appear as a non sequitur, there could be for the doomed hero a prospect of relief, where the final outcome is in doubt.[19]

Catastrophe

The catastrophe ("Katastrophe" in the original)[13] is where the hero meets his logical destruction. Freytag warns the writer not to spare the life of the hero.[20] More generally, the final result of a work's main plot has been known in English since 1705 as the denouement (UK: /deɪˈnuːmɒ̃, dɪ-/, US: /ˌdeɪnuːˈmɒ̃/;[21]). It comprises events from the end of the falling action to the actual ending scene of the drama or narrative. Conflicts are resolved, creating normality for the characters and a sense of catharsis, or release of tension and anxiety, for the reader. Etymologically, the French word dénouement (French: [denumɑ̃]) is derived from the word dénouer, "to untie", from nodus, Latin for "knot." It is the unraveling or untying of the complexities of a plot.

The comedy ends with a denouement (a conclusion), in which the protagonist is better off than at the story's outset. The tragedy ends with a catastrophe, in which the protagonist is worse off than at the beginning of the narrative. Exemplary of a comic denouement is the final scene of Shakespeare's comedy As You Like It, in which couples marry, an evildoer repents, two disguised characters are revealed for all to see, and a ruler is restored to power. In Shakespeare's tragedies, the denouement is usually the death of one or more characters.[22]

Northrop Frye’s dramatic structure

The Canadian literary critic and theorist Northrop Frye analyzes the narratives of the Bible in terms of two dramatic structures: (1) a U-shaped pattern, which is the shape of a comedy, and (2) an inverted U-shaped pattern, which is the shape of a tragedy.

A U-shaped pattern

“This U-shaped pattern…recurs in literature as the standard shape of comedy, where a series of misfortunes and misunderstandings brings the action to a threateningly low point, after which some fortunate twist in the plot sends the conclusion up to a happy ending.”[23] A U-shaped plot begins at the top of the U with a state of equilibrium, a state of prosperity or happiness, which is disrupted by disequilibrium or disaster. At the bottom of the U, the direction is reversed by a fortunate twist, divine deliverance, an awakening of the protagonist to his or her tragic circumstances, or some other action or event that results in an upward turn of the plot.[24] Aristotle referred to the reversal of direction as peripeteia or peripety,[25] which depends frequently on a recognition or discovery by the protagonist. Aristotle called this discovery an anagnorisis—a change from “ignorance to knowledge” involving “matters which bear on prosperity or adversity”.[26] The protagonist recognizes something of great importance that was previously hidden or unrecognized. The reversal occurs at the bottom of the U and moves the plot upward to a new stable condition marked by prosperity, success, or happiness. At the top of the U, equilibrium is restored.

A classic example of a U-shaped plot in the Bible is the Parable of the Prodigal Son in Luke 15:11-24. The parable opens at the top of the U with a stable condition but turns downward after the son asks the father for his inheritance and sets out for a “distant country” (Luke 15:13). Disaster strikes: the son squanders his inheritance and famine in the land increases his dissolution (Luke 15:13-16). This is the bottom of the U. A recognition scene (Luke 15:17) and a peripety move the plot upward to its denouement, a new stable condition at the top of the U.

An inverted U-shaped structure

The inverted U begins with the protagonist’s rise to a position of prominence and well-being. At the top of the inverted U, the character enjoys good fortune and well-being. But a crisis or a turning point occurs, which marks the reversal of the protagonist’s fortunes and begins the descent to disaster. Sometimes a recognition scene occurs where the protagonist sees something of great importance that was previously unrecognized. The final state is disaster and adversity, the bottom of the inverted U.

An example of an inverted U-shaped pattern is found in the parable of the Ten Virgins in Matthew 25:1-13. The rising action is the preparation for the coming of the bridegroom by the ten virgins, but a crisis occurs when the bridegroom, who was delayed for the wedding, appears unexpectedly at midnight. This is the turning point, the reversal or peripety, that leads to disaster for the five bridesmaids that were not prepared for the bridegroom’s delay. The recognition (anagnorisis) of their hamartia or their tragic flaw is apparent to the reader but occurs too late for the foolish bridesmaids to avert disaster (cf. Matthew 25:12).[27]

Criticism

Contemporary dramas increasingly use the fall to increase the relative height of the climax and dramatic impact (melodrama). The protagonist reaches up but falls and succumbs to doubts, fears, and limitations. The negative climax occurs when the protagonist has an epiphany and encounters the greatest fear possible or loses something important, giving the protagonist the courage to take on another obstacle. This confrontation becomes the classic climax.[28]

See also

- Jo-ha-kyū – dramatic arc in Japanese aesthetics

- Kishōtenketsu – a structural arrangement used in traditional Chinese and Japanese narratives

- Narrative transportation

- Scene and sequel

- Sonata form

- Three-act structure

Notes

- Northrop Frye, The Great Code (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982, 1981).

- Perseus Digital Library (2006). Aristotle, Poetics

- University of South Carolina (2006). The Big Picture Archived October 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- University of Illinois: Department of English (2006). Freytag’s Triangle Archived July 16, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Freytag (1900, p. 115)

- Aristotle, "Poetics", Project Gutenberg, Section VII

- Aristotle, "Poetics", Project Gutenberg, Section XVIII

- Aristotle, "Poetics", Project Gutenberg, Section XVIII

- Aristotle, "Poetics", Project Gutenberg, Section VI

- Aristotle, "Poetics", Project Gutenberg, Section XI

- Aristotle, "Poetics", Project Gutenberg, Section XIII

- Freytag (1900, p. 115)

- Freytag, Gustav (1863). Die Technik des Dramas (in German). Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- Freytag (1900, p. 104-105)

- Freytag (1900, p. 115)

- Freytag (1900, pp. 115–121)

- Freytag (1900, pp. 125–128)

- Freytag (1900, pp. 128–130)

- Freytag (1900, pp. 133–135)

- Freytag (1900, pp. 137–140)

- "dénouement". Cambridge Dictionary.

- "What is a Denouement?". Writer's Digest. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Frye, Great Code, 169.

- James L. Resseguie, Narrative Criticism of the New Testament: An Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2005), 205.

- Aristotle, Poetics, Loeb Classical Library 199, ed. and trans. by Stephen Halliwell (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 11.

- Ibid.

- James L. Resseguie, "A Glossary of New Testament Narrative Criticism with Illustrations," in Religions, 10 (3: 217), 21.

- Teruaki Georges Sumioka: The Grammar of Entertainment Film 2005, ISBN 978-4-8459-0574-4; lectures at Johannes-Gutenberg-University in German

References

- Freytag, Gustav (1900) [Copyright 1894], Freytag's Technique of the Drama, An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art by Dr. Gustav Freytag: An Authorized Translation From the Sixth German Edition by Elias J. MacEwan, M.A. (3rd ed.), Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company, LCCN 13-283

External links

| Look up dénouement in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- English translation of Freytag's Die Technik des Dramas

- Another view on dramatic structure

- What’s Right With The Three Act Structure by Yves Lavandier, author of Writing Drama

- Other scholarly analyses

- Poetics, by Aristotle

- European Theories of the Drama, edited by Barrett H. Clark

- The New Art of Writing Plays, by Lope de Vega

- The Drama; Its Laws and Its Technique, by Elisabeth Woodbridge Morris

- The Technique of the Drama, by W.T. Price

- The Analysis of Play Construction and Dramatic Principle, by W.T. Price

- The Law of the Drama, by Ferdinand Brunetière

- Play-making: A Manual of Craftsmanship, by William Archer

- Dramatic Technique, by George Pierce Baker

- Theory and Technique of Playwriting, by John Howard Lawson

- Writing Drama by Yves Lavandier