Malassezia

Malassezia (formerly known as Pityrosporum) is a genus of fungi. Malassezia is naturally found on the skin surfaces of many animals, including humans. In occasional opportunistic infections, some species can cause hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation on the trunk and other locations in humans. Allergy tests for this fungus are available.

| Malassezia | |

|---|---|

| |

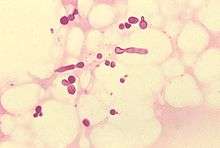

| Malassezia furfur in skin scale from a patient with tinea versicolor | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | Malasseziales |

| Family: | Malasseziaceae |

| Genus: | Malassezia |

Nomenclature

Due to progressive changes in their nomenclature, some confusion exists about the naming and classification of Malassezia yeast species. Work on these yeasts has been complicated because they require specific growth media and grow very slowly in laboratory culture.

Malassezia were originally identified by the French scientist Louis-Charles Malassez in the late 19th century. Raymond Sabouraud identified a dandruff-causing organism in 1904 and called it "Pityrosporum malassez", honoring Malassez, but at the species level as opposed to the genus level. When it was determined that the organisms were the same, the term "Malassezia" was judged to possess priority.[2]

In the mid-20th century, it was reclassified into two species:

- Pityrosporum (Malassezia) ovale, which is lipid-dependent and found only on humans. P. ovale was later divided into two species, P. ovale and P. orbiculare, but current sources consider these terms to refer to a single species of fungus, with M. furfur the preferred name.[3]

- Pityrosporum (Malassezia) pachydermatis, which is lipophilic but not lipid-dependent. It is found on the skin of most animals.

In the mid-1990s, scientists at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France, discovered additional species.[4]

Currently there are at least 17 recognized species:

- M. caprae[5]

- M. cuniculi[6]

- M. dermatis[7]

- M. equina[5]

- M. furfur

- M. globosa[8]

- M. japonica[9]

- M. nana[10]

- M. obtusa

- M. pachydermatis[11]

- M. restricta[12]

- M. slooffiae[13]

- M. sympodialis[14]

- M. yamatoensis[15]

- M. psittaci[16]

...

Role in human diseases

Identification of Malassezia on skin has been aided by the application of molecular or DNA-based techniques. These investigations show that the Malassezia species causing most skin disease in humans, including the most common cause of dandruff and seborrhoeic dermatitis, is M. globosa (though M. restricta is also involved).[8] The skin rash of tinea versicolor (pityriasis versicolor) is also due to infection by this fungus.

As the fungus requires fat to grow,[4] it is most common in areas with many sebaceous glands: on the scalp,[17] face, and upper part of the body. When the fungus grows too rapidly, the natural renewal of cells is disturbed, and dandruff appears with itching (a similar process may also occur with other fungi or bacteria).

A project in 2007 has sequenced the genome of dandruff-causing Malassezia globosa and found it to have 4,285 genes.[18] M. globosa uses eight different types of lipase, along with three phospholipases, to break down the oils on the scalp. Any of these 11 proteins would be a suitable target for dandruff medications.

M. globosa has been predicted to have the ability to reproduce sexually,[19] but this has not been observed.

The fungus appears to play a role in the development of some pancreatic cancers, as a result of it migrating from the gut lumen to the pancreas.[20]

The number of specimens of M. globosa on a human head can be up to ten million.[17]

Treatment of symptomatic scalp infections

Symptomatic scalp infections are often treated with selenium disulfide,[21] zinc pyrithione, or ketoconazole containing shampoos.

There are several natural antifungal remedies for seborrhoeic dermatitis including garlic, onions, coconut oil, apple cider vinegar, Tea tree oil (Melaleuca alternifolia oil), honey, and cinnamic acid.[22][23][24] The efficacy of these natural treatments can vary considerably between individuals.

References

- Ran Yuping (2016). "Observation of Fungi, Bacteria, and Parasites in Clinical Skin Samples Using Scanning Electron Microscopy". In Janecek, Milos; Kral, Robert (eds.). Modern Electron Microscopy in Physical and Life Sciences. InTech. doi:10.5772/61850. ISBN 978-953-51-2252-4.

- Inamadar AC, Palit A (2003). "The genus Malassezia and human disease". Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 69 (4): 265–70. PMID 17642908.

- Freedberg; et al., eds. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 1187. ISBN 0-07-138067-1.

- Guého E, Midgley G, Guillot J (May 1996). "The genus Malassezia with description of four new species". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 69 (4): 337–55. doi:10.1007/BF00399623. PMID 8836432.

- Cabañes, FJ, Theelen, B, Castella, G, Boukhout, T (2007). "Two new lipid-dependent Malassezia species from domestic animals". FEMS Yeast Research. 7 (6): 1064–1076. doi:10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00217.x. ISSN 1567-1356. PMID 17367513.

- Cabañes FJ, Vega S, Castellá G (2011). "Malassezia cuniculi sp. nov., a novel yeast species isolated from rabbit skin". Medical Mycology. 49 (1): 40–48. doi:10.3109/13693786.2010.493562. PMID 20560865.

- Sugita T, Takashima M, Shinoda T, et al. (April 2002). "New Yeast Species, Malassezia dermatis, Isolated from Patients with Atopic Dermatitis". J. Clin. Microbiol. 40 (4): 1363–7. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.4.1363-1367.2002. PMC 140359. PMID 11923357.

- DeAngelis YM, Saunders CW, Johnstone KR, et al. (September 2007). "Isolation and expression of a Malassezia globosa lipase gene, LIP1". J. Invest. Dermatol. 127 (9): 2138–46. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700844. PMID 17460728.

- Sugita, Takashi; Masako Takashima; Minako Kodama; Ryoji Tsuboi; Akemi Nishikawa (October 2003). "Description of a New Yeast Species, Malassezia japonica, and Its Detection in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis and Healthy Subjects". J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 (10): 4695–4699. doi:10.1128/JCM.41.10.4695-4699.2003. PMC 254348. PMID 14532205.

- Hirai A, Kano R, Makimura K, et al. (March 2004). "Malassezia nana sp. nov., a novel lipid-dependent yeast species isolated from animals". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54 (Pt 2): 623–7. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02776-0. PMID 15023986.

- Coutinho SD, Paula CR (June 1998). "Biotyping of Malassezia pachydermatis strains using the killer system". Rev Iberoam Micol. 15 (2): 85–7. PMID 17655416.

- Sugita T, Tajima M, Amaya M, Tsuboi R, Nishikawa A (2004). "Genotype analysis of Malassezia restricta as the major cutaneous flora in patients with atopic dermatitis and healthy subjects". Microbiol. Immunol. 48 (10): 755–9. doi:10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03601.x. PMID 15502408.

- Uzal FA, Paulson D, Eigenheer AL, Walker RL (October 2007). "Malassezia slooffiae-associated dermatitis in a goat". Vet. Dermatol. 18 (5): 348–52. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3164.2007.00606.x. PMID 17845623.

- Niamba P, Weill FX, Sarlangue J, Labrèze C, Couprie B, Taïeh A (August 1998). "Is common neonatal cephalic pustulosis (neonatal acne) triggered by Malassezia sympodialis?". Arch Dermatol. 134 (8): 995–8. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.8.995. PMID 9722730.

- Sugita T, Tajima M, Takashima M, et al. (2004). "A new yeast, Malassezia yamatoensis, isolated from a patient with seborrheic dermatitis, and its distribution in patients and healthy subjects". Microbiol. Immunol. 48 (8): 579–83. doi:10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03554.x. PMID 15322337.

- Lorch JM, Palmer JM, Vanderwolf KJ, et al. (2018). "Malassezia vespertilionis sp. nov. :a new cold-tolerant species of yeast isolated from bats". Persoonia. 41: 56–70. doi:10.3767/persoonia.2018.41.04. PMC 6344816. PMID 30728599.

- "Genetic code of dandruff cracked". BBC News. 6 November 2007. Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- Xu J, Saunders CW, Hu P, et al. (November 2007). "Dandruff-associated Malassezia genomes reveal convergent and divergent virulence traits shared with plant and human fungal pathogens". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (47): 18730–5. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10418730X. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706756104. PMC 2141845. PMID 18000048.

- Guillot J, Hadina S, Guého E (June 2008). "The genus Malassezia: old facts and new concepts". Parassitologia. 50 (1–2): 77–9. PMID 18693563.

- Aykut, Berk; Pushalkar, Smruti; Chen, Ruonan; Li, Qianhao; Abengozar, Raquel; Kim, Jacqueline I.; Shadaloey, Sorin A.; Wu, Dongling; Preiss, Pamela; Verma, Narendra; Guo, Yuqi; Saxena, Anjana; Vardhan, Mridula; Diskin, Brian; Wang, Wei; Leinwand, Joshua; Kurz, Emma; Kochen Rossi, Juan A.; Hundeyin, Mautin; Zambrinis, Constantinos; Li, Xin; Saxena, Deepak; Miller, George (October 2019). "The fungal mycobiome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via activation of MBL". Nature. 574 (7777): 264–267. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1608-2. PMC 6858566. PMID 31578522.

- DermNet treatments/selenium Retrieved Dec 24, 2007..

- Gupta, Aditya K; Nicol, Karyn; Batra, Roma (2004). "Role of Antifungal Agents in the Treatment of Seborrheic Dermatitis". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 5 (6): 417–422. doi:10.2165/00128071-200405060-00006. PMID 15663338.

- Al-Waili, N. S. (2001). "Therapeutic and prophylactic effects of crude honey on chronic seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff". European Journal of Medical Research. 6 (7): 306–8. PMID 11485891.

- Shams-Ghahfarokhi, Masoomeh; Shokoohamiri, Mohammad-Reza; Amirrajab, Nasrin; Moghadasi, Behnaz; Ghajari, Ali; Zeini, Farideh; Sadeghi, Golnar; Razzaghi-Abyaneh, Mehdi (June 2006). "In vitro antifungal activities of Allium cepa, Allium sativum and ketoconazole against some pathogenic yeasts and dermatophytes". Fitoterapia. 77 (4): 321–323. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2006.03.014. PMID 16690223.

External links

- Shams Ghahfarokhi, M.; Razzaghi Abyaneh, M. (4 October 2015). "Rapid Identification of Malassezia furfur from other Malassezia Species: A Major Causative Agent of Pityriasis Versicolor". Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences. 29 (1): 36–39. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.611.20.

- Noble SL, Forbes RC, Stamm PL (July 1998). "Diagnosis and management of common tinea infections". Am Fam Physician. 58 (1): 163–74, 177–8. PMID 9672436.