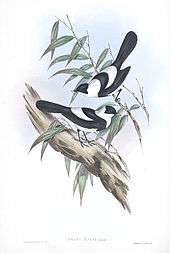

Pied monarch

The pied monarch (Arses kaupi) is a species of bird in the monarch-flycatcher family, Monarchidae. It is endemic to coastal Queensland in Australia.

| Pied monarch[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male in Australia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Monarchidae |

| Genus: | Arses |

| Species: | A. kaupi |

| Binomial name | |

| Arses kaupi Gould, 1851 | |

Taxonomy and systematics

The pied monarch was described by John Gould in 1851, who deliberated on placing it in a genus by itself on account of its feet and eye ring. The nest and eggs were undescribed until collected by Robert Hislop on 3 December 1894 near Bloomfield River.[3]

The pied monarch is closely related to and forms a superspecies with the two other species of monarch flycatcher in the genus Arses. Two subspecies are recognised, however they two intergrade where their ranges meet at Mossman, and they could be treated as a monotypic species.[4] The monarch flycatchers are classified either as a subfamily Monarchinae, together with the fantails as part of the drongo family Dicruridae,[5] or as a family Monarchidae in its own right.[6] Molecular research in the late 1980s and early 1990s revealed the monarchs belong to a large group of mainly Australasian birds known as the Corvida parvorder comprising many tropical and Australian passerines.[7] More recently, the grouping has been refined somewhat as the monarchs have been classified in a 'Core corvine' group with the crows and ravens, shrikes, birds of paradise, fantails, drongos and mudnest builders.[8]

Alternate names include the Australian pied flycatcher, Australian pied monarch, banded monarch, pied monarch-flycatcher, black-breasted flycatcher, Kaup's flycatcher and pied flycatcher.

Subspecies

Two subspecies are recognized:[9]

- A. k. terraereginae - Campbell, AJ, 1895: Found on eastern Cape York Peninsula (north-eastern Australia)

- A. k. kaupi - Gould, 1851: Found on south-eastern Cape York Peninsula (north-eastern Australia)

Description

The pied monarch is 15–16 centimetres (5.9–6.3 in) in length and weighs around 12.5–15 grams (0.44–0.53 oz). The plumage is sexually dimorphic. The upperparts and head of the male are black, as is the tail, and the wings are brownish-black with white scapulars (which shows as a white crescent across the back when folded). The collar, which is erectable, is white, and it joins through the neck with a white throat. The breast-band is black, and the belly and underside are white. In the female the white on the throat and collar is less distinct and covers less area, and the collar is incomplete around the neck. The eye is black, and is surrounded by a blue coloured eye-ring, which is less distinct in the female. The bill is blue-grey, and the legs are black. Immature birds look like females but with duller plumage, no blue in the eye-rings, and a horn-coloured bill.[4] Like other members of the genus it has long hind-toes and claws, and in general the size and shape of the feet resemble those of the Australasian treecreepers, and the feet are used for feeding in the same manner on the trunks of trees.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The pied monarch is found in tropical forest edge habitats and secondary growth in coastal north eastern Queensland, from Cooktown to Ingham. It ranges from sea level up to 900 metres (3,000 ft). It also occurs in palm-vine scrub, gallery forest and along rivers. The species is mostly non-migratory, but some birds disperse to the Eucalyptus woodland in the Atherton Tableland during the winter.[4]

The species has a tiny global range, and is described as uncommon and occurring at low densities throughout its range. However much of its range is protected within national parks or World Heritage Sites, and its habitat is thought to be secure. The species is considered to be safe at the moment, and is listed as Least Concern by the IUCN.[4]

Behaviour

The pied monarch is insectivorous, with beetles (Coleoptera) and moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera) being recorded in its diet. It is usually seen as singles or pairs and small groups (of three to five birds, which may be family groups). They join mixed-species foraging flocks with other monarch flycatchers, fantails, whistlers and shrikethrushes. Within the forest they usually feed at the mid level, and rarely close to the ground. One foraging method typical to the genus is to climb up trunks and the larger branches in the manner of a treecreeper (Climacteris) and probing the bark and lichens, but they also catch prey from the air.[4]

Breeding

Breeding season is October to January with one brood raised. The nest is a shallow cup made of vines and sticks, woven together with spider webs and shredded plant material, and decorated with lichen on the outside. It is generally sited on a hanging loop of vine well away from the trunk or foliage of a sizeable tree about 2–10 metres (6.6–32.8 ft) above the ground. Two pink-tinged oval white eggs splotched with lavender and reddish-brown are laid measuring 19 mm x 14 mm.[10]

References

- Gill, F.; Donsker, D., eds. (2011). "Vireos, Crows and Allies". IOC World Bird Names (version 2.10). Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- BirdLife International (2016). "Arses kaupi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22707351A94118989. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22707351A94118989.en.

- Favaloro, Norman J. (1931). "Notes on Arses kaupi and Arses lorealis" (PDF). Emu. 30 (4): 241–242. doi:10.1071/MU930241.

- Coates, Brian; Dutson, Guy; Filardi, Chris; Clement, Peter; Gregory, Phil; Moeliker, Kees (2007). "Family Monarchidae (Monarch-flycatchers)". In Josep, del Hoyo; Andrew, Elliott; David, Christie (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 11, Old World Flycatchers to Old World Warblers. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. pp. 315–16. ISBN 84-96553-06-X.

- Christidis L, Boles WE (1994). The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories. Melbourne: RAOU.

- Christidis L, Boles WE (2008). Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds. Canberra: CSIRO Publishing. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-643-06511-6.

- Sibley, Charles Gald & Ahlquist, Jon Edward (1990): Phylogeny and classification of birds. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

- Cracraft J, Barker FK, Braun M, Harshman J, Dyke GJ, Feinstein J, Stanley S, Cibois A, Schikler P, Beresford P, García-Moreno J, Sorenson MD, Yuri T, Mindell DP (2004). "Phylogenetic relationships among modern birds (Neornithes): toward an avian tree of life". In Cracraft J, Donoghue MJ (eds.). Assembling the tree of life. New York: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 468–89. ISBN 0-19-517234-5.

- "IOC World Bird List 6.4". IOC World Bird List Datasets. doi:10.14344/ioc.ml.6.4.

- Beruldsen, Gordon (2003). Australian Birds: Their Nests and Eggs (2nd ed.). Kenmore Hills, Qld: self. p. 364. ISBN 0-646-42798-9.