Phycomycosis

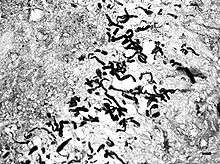

Phycomycosis is an uncommon condition of the gastrointestinal tract and skin most commonly found in dogs and horses. The condition is caused by a variety of molds and fungi, and individual forms include pythiosis, zygomycosis, and lagenidiosis. Pythiosis is the most common type and is caused by Pythium, a type of water mould. Zygomycosis can also be caused by two types of zygomycetes, Entomophthorales (such as Basidiobolus and Conidiobolus) and Mucorales (such as Mucor, Mortierella, Absidia, Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, and Saksenaea).[1] The latter type of zygomycosis is also referred to as mucormycosis. Lagenidiosis is caused by a Lagenidium species, which like Pythium is a water mould. Since both pythiosis and lagenidiosis are caused by organisms from the class Oomycetes, they are sometimes collectively referred to as oomycosis.

| Phycomycosis | |

|---|---|

| Causes | Pythium insidiosum |

Pythiosis

Pythiosis is caused by Pythium insidiosum and occurs most commonly in dogs and horses, but is also found in cats, cattle, and humans. In the United States it is most commonly found in the Gulf states, especially Louisiana, but has been found in midwest and eastern states. It is also found in southeast Asia, eastern Australia, New Zealand, and South America. Pythiosis occurs in areas with mild winters due to the organism surviving in standing water that does not reach freezing temperatures.[2] Pythium occupies swamps in late summer and infects dogs who drink water containing it. The disease is typically found in young, large breed dogs.[1]

It is suspected that pythiosis is caused by invasion of the organism into wounds, either in the skin or in the gastrointestinal tract.[2] The disease grows slowly in the stomach and small intestine, eventually forming large lumps of granulation tissue. It can also invade surrounding lymph nodes. Symptoms include vomiting, diarrhea, depression, weight loss, and a mass in the abdomen. Pythiosis of the skin in dogs is very rare, and appears as ulcerated lumps. Primary infection can also occur in the bones and lungs.

In horses, subcutaneous pythiosis is the most common form and infection occurs through a wound while standing in water containing the pathogen.[3] The disease is also known as leeches, swamp cancer, and bursatti. Lesions are most commonly found on the lower limbs, abdomen, chest, and genitals. They are granulomatous and itchy, and may be ulcerated or fistulated. The lesions often contain yellow, firm masses of dead tissue known as kunkers.[4] It is possible with chronic infection for the disease to spread to underlying bone.[5]

In humans it can cause arteritis, keratitis, and periorbital cellulitis.[6]

In cats pythioisis is almost always confined to the skin as hairless and edematous lesions. It is usually found on the limbs, perineum, and at the base of the tail.[7] Lesions may also develop in the nasopharynx.[4]

Pythium insidiosum is different from other members of the genus in that human and horse hair, skin, and decaying animal tissue are chemoattractants for its zoospores, in addition to decaying plant tissue.[3]

Zygomycosis

Zygomycosis usually is a disease of the skin, but can also occur in the sinuses or gastrointestinal tract. In humans it is most prevalent in immunocompromised patients (HIV/AIDS, the elderly, SCID, etc) and patients in acidosis (diabetes, burns), particularly after barrier injury to the skin or mucus membranes. Zygomycosis caused by Mucorales causes a rapidly progressing disease of sudden onset in sick or immunocompromised animals. Entomophthorales cause chronic, local infections in otherwise healthy animals. The important species that cause entomophthoromycosis are Conidiobolus coronatus, C. incongruous, and Basidiobolus ranarum. Conidiobolus infections of the upper respiratory system have been reported in humans, sheep, horses, and dogs, and Basidiobolus has been reported less commonly in humans and dogs.[8] Horses are one of the most common domestic animals to be affected by entomophthoromycosis. C. coronatus causes lesions in the nasal and oral mucosa of horses that may cause nasal discharge or difficulty breathing. B. ranarum causes large circular nodules on the upper body and neck of horses.[9] Entomophthorales is found in soil and decaying plant matter, and specifically Basidiobolus can be contracted from insects and the feces of reptiles or amphibians.[6]

Zygomycosis of the sinuses can extend from the sinuses into the orbit and the cranial vault, leading to rhinocerebral mucormycosis.

Lagenidiosis

The best known species of Lagenidium is Lagenidium giganteum, a parasite of mosquito larvae used in biological control of mosquitoes. Two different species cause disease exclusively in dogs: L. caninum and L. karlingii. Lagenidiosis is found in the southeastern United States in lakes and ponds. It causes progressive skin and subcutaneous lesions in the legs, groin, trunk, and near the tail. The lesions are firm nodules or ulcerated regions with draining tracts. Regional lymph nodes are usually swollen. Spread of the disease to distant lymph nodes, large blood vessels, and the lungs may occur.[6] An aneurysm of a great vessel can rupture and cause sudden death.[4] L. caninum is the more aggressive species and is more likely to spread to other organs than L. karlingii.[10]

Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis is through biopsy or culture, although an ELISA test has been developed for Pythium insidiosum in animals.[11] Treatment is very difficult and includes surgery when possible. Postoperative recurrence is common. Antifungal drugs show only limited effect on the disease, but itraconazole and terbinafine hydrochloride are often used for two to three months following surgery.[6] Humans with Basidiobolus infections have been treated with amphotericin B and potassium iodide.[8] For pythiosis and lagenidiosis, a new drug targeting water moulds called caspofungin is available, but it is very expensive.[6] Immunotherapy has been used successfully in humans and horses with pythiosis.[11] The prognosis for any type of phycomycosis is poor.

References

- Ettinger, Stephen J.;Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th. ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-6795-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Helman R, Oliver J (1999). "Pythiosis of the digestive tract in dogs from Oklahoma". J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 35 (2): 111–4. doi:10.5326/15473317-35-2-111. PMID 10102178.

- Liljebjelke K, Abramson C, Brockus C, Greene C (2002). "Duodenal obstruction caused by infection with Pythium insidiosum in a 12-week-old puppy". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 220 (8): 1188–91, 1162. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.220.1188. PMID 11990966.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Oomycosis". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-03.

- Worster A, Lillich J, Cox J, Rush B (2000). "Pythiosis with bone lesions in a pregnant mare". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 216 (11): 1795–8, 1760. doi:10.2460/javma.2000.216.1795. PMID 10844973.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Grooters A (2003). "Pythiosis, lagenidiosis, and zygomycosis in small animals". Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 33 (4): 695–720, v. doi:10.1016/S0195-5616(03)00034-2. PMID 12910739.

- Wolf, Alice (2005). "Opportunistic fungal infections". In August, John R. (ed.). Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine Vol. 5. Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-0423-4.

- Greene C, Brockus C, Currin M, Jones C (2002). "Infection with Basidiobolus ranarum in two dogs". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 221 (4): 528–32, 500. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.221.528. PMID 12184703.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Zygomycosis". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-03.

- Todd-Jenkins, Karen (September 2007). "A new disease: clinically interesting for all the right reasons". Veterinary Forum. Veterinary Learning Systems. 24 (9): 18–20.

- Hensel P, Greene C, Medleau L, Latimer K, Mendoza L (2003). "Immunotherapy for treatment of multicentric cutaneous pythiosis in a dog". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 223 (2): 215–8, 197. doi:10.2460/javma.2003.223.215. PMID 12875449.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

| Classification |

|---|