Photogram

A photogram [from the combining form φωτω- (phōtō-) of Ancient Greek φῶς (phôs, “light”), and Ancient Greek suffix -γραμμα (-gramma), from γράμμα (grámma, “written character, letter, that which is drawn”), from γράφω (gráphō, “to scratch, to scrape, to graze”)] is a photographic image made without a camera by placing objects directly onto the surface of a light-sensitive material such as photographic paper and then exposing it to light.

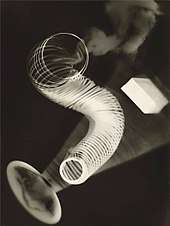

The usual result is a negative shadow image that shows variations in tone that depends upon the transparency of the objects used. Areas of the paper that have received no light appear white; those exposed for a shorter time or through transparent or semi-transparent objects appear grey,[1] while fully exposed areas are black in the final print.

The technique is sometimes called cameraless photography.[2][3][4] It was used by Man Ray in his exploration of rayographs. Other artists who have experimented with the technique include László Moholy-Nagy, Christian Schad (who called them "Schadographs"), Imogen Cunningham and Pablo Picasso.[5]

Variations of the technique have also been used for scientific purposes, in shadowgraph studies of flow in transparent media and in high-speed Schlieren photography, and in the medical X-Ray.

History

Prehistory

The phenomenon of the shadow has always aroused human curiosity and inspired artistic representation, as recorded by Pliny the Elder,[6] and various forms of shadow play since the 1st millennium BCE.[7][8] The photogram in essence is a means by which the fall of light and shade on a surface may be automatically captured and preserved.[9][3] To do so required a substance that would react to light, and from the 17th century photochemical reactions were progressively observed or discovered in salts of silver, iron, uranium and chromium. In 1725 Johann Heinrich Schulze was the first to demonstrate a temporary photographic effect in silver salts, confirmed by Carl Wilhhelm Scheele in 1777, who found that violet light caused the greatest reaction in silver chloride. Humphry Davy and Thomas Wedgewood reported[10] that they had produced pictures from stencils on leather and paper, but had no means of fixing them[11] and some organic substances respond to light, as evidenced in sunburn (an effect used by Dennis Oppenheim in his 1970 Reading Position for Second Degree Burn) and photosynthesis (with which Lloyd Godman forms images[12]).

Nineteenth century

The first photographic negatives made were photograms (though the first permanent photograph was made with a camera by Niécephore Niépce). William Henry Fox Talbot called these photogenic drawings, which he made by placing leaves or pieces of lace onto sensitized paper, then left them outdoors on a sunny day to expose. This produced a dark background with a white silhouette of the placed object.[13]

As an advance on the ancient art of nature prints,[14] in which specimens were inked to make an impression on paper, from 1843, Anna Atkins produced a book titled British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions in instalments; the first to be illustrated with photographs. The images were all photograms of botanical specimens, mostly seaweeds, which she made using Sir John Herschel's cyanotype process, which yields blue images.[15] This very rare book can be seen in the National Media Museum in Bradford, England.

Modernism

In Modernism, and especially in Dada[16][17][18] and Constructivism[19][20] and in the formalist dissections of the Bauhaus,[21][22] the photogram enabled experiments in abstraction by Christian Schad as early as 1918,[23] Man Ray in 1921, and Moholy-Nagy in 1922,[24] through dematerialisation and distortion, merging and interpenetration of forms, and flattening of perspective.

Christian Schad's 'schadographs'

In 1918 Christian Schad's experiments with the photogram were inspired by Dada, creating photograms from random arrangements of discarded objects he had collected such as torn tickets, receipts and rags. Some argue that he was the first to make this an art form, preceding Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy by at least a year or two,[25] and one was published in March 1920 in the magazine Dadaphone[26] by Tristan Tzara, who dubbed them 'Schadographs'.[27]

Man Ray's 'rayographs'

Photograms were used in the 20th century by a number of photographers, particularly Man Ray, whose "rayographs" were also given the name by Dada leader Tzara.[27] Ray described his (re-)discovery of the process in his 1963 autobiography;[28]

"Again at night I developed the last plates I had exposed; the following night I set to work printing them. Besides the trays and chemical solutions in bottles, a glass graduate and thermometer, a box of photographic paper, my laboratory equipment was nil. Fortunately, I had to make only contact prints from the plates. I simply laid a glass negative on a sheet of light-sensitive paper on the table, by the light of my little red lantern, turned on the bulb that hung from the ceiling, for a few seconds, and developed the prints. It was while making these prints that I hit on my Rayograph process, or cameraless photographs. One sheet of photo paper got into the developing tray - a sheet unexposed that had been mixed with those already exposed under the negatives - I made my several exposures first, developing them together later - and as I waited in vain a couple of minutes for an image to appear, regretting the waste paper, I mechanically placed a small glass funnel, the graduate and the thermometer in the tray on the wetted paper, I turned on the light: before my eyes an image began to form, not quite a simple silhouette of the objects as in a straight photograph, but distorted and refracted by the glass more or less in contact with the paper and standing out against a black background, the part directly exposed to the light. I remembered when I was a boy placing fern leaves in a printing frame with proof paper, exposing it to sunlight, and obtaining a white negative of the leaves. This was the same idea, but with an added three-dimensional quality and tonal gradation."

In his photograms, Man Ray made combinations of objects—a comb, a spiral of cut paper, an architect’s French curve—some recognisable, others transformed, typifying Dada's rejection of 'style', emphasising chance and abstraction.[17] He published a selection of these rayographs as Champs délicieux in December 1922, with an introduction by Tzara. His 1923 film Le Retour à la Raison ('Return to Reason') adapts rayograph technique to moving images.[29]

Other 20th century artists

In the 1930s artists including Theodore Roszak, and Piet Zwart made photograms while Luigi Veronesi combined the photographic image with oil on canvas in large-scale colour images by preparing a light-sensitive canvas on which he placed objects in the dark for exposure and then fixing.[30] The shapes became the matrix for an abstract painting to which he applied colour and added drawn geometric lines to enhance the dynamics, exhibiting them at the Galerie L’Equipe in Paris in 1938-1939.[31][32] Bronislaw Schlabs, Julien Coulommier, Andrzej Pawlowski, Beksinki and Kurt Wendlandt were photogram artists in the 1940s and 1950s; Lina Kolarova, Rene Mächler, and Andreas Mulas in the 1970s; and Tony Ceballos, Kare Magnole, Andreas Müller-Pohle, and Floris M. Neusüss in the 1980s.[27]

Contemporary

Established contemporary artists who are widely known for using photograms are Adam Fuss,[33] Susan Derges and Christian Marclay, and younger artists worldwide[34] continue to value the materiality of the technique in the digital age.[35]

Procedure

The customary approach to making a photogram is to use a darkroom and enlarger and to proceed as one would in making a conventional print, but instead of using a negative, to arrange objects on top of a piece of photographic paper for exposure under the enlarger lamp which can conveniently be controlled with the timer switch and aperture controls. That will give a result similar to the image at left; since the enlarger emits light through a lens aperture, the shadows of even tall objects like the beaker standing upright on the paper will stay sharp; the more so at smaller apertures.

The print is then processed, washed, and dried.[36]

At this stage the image will look similar to a negative, in which shadows are white. A contact-print onto a fresh sheet of photographic paper will reverse the tones if a more naturalistic result is desired, which may be facilitated by making the initial print on film.[37]

However, there are other arrangements for making photograms, and devising them is part of the creative process. Alice Lex-Nerlinger used the conventional darkroom approach in making photograms as a variation on her airbrushed stencil paintings,[38] since lighting penetrating the translucent paper from which she cut her pictures would print a variegated texture she could not otherwise obtain.

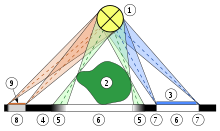

One variable is the light source, or sources, used.[39] A broad source of light will cast nuances of shadow; umbra, penumbra and antumbra, as shown in the accompanying diagram.

Photograms may be made outdoors providing the photographic emulsion is sufficiently slow to permit it. Direct sunlight is a point-source of light (like that of an enlarger), while cloudy conditions give soft-edged shadows around three-dimensional objects placed on the photosensitive surface. The cyanotype process ('blueprints') such as that used by Anna Atkins (see above), is slow and insensitive enough that coating it on paper, fabric, timber or other supports can be done in subdued light indoors. Exposure outdoors may take many minutes depending on conditions, and its progress may be gauged by inspection as the coating darkens. 'Printing-out paper' or other daylight-printing material such as gum bichromate may also enable outdoor exposure. Christian Schad simply placed tram tickets and other ephemera under glass on printing-out paper on his window-sill for exposure.[25]

Conventional monochrome or colour, or direct-positive photographic material may be exposed in the dark using a flash unit, as does Adam Fuss for his photograms that capture the movement of a crawling baby, or an eel in shallow water. Susan Derges captures water currents in the same way, while Harry Nankin[40] has immersed large sheets of monochrome photographic paper at the edge of the sea and mounted a flash on a specially-constructed oversize tripod above it to capture the action of waves and seaweeds washing over the paper surface.

Other variations include using the light of a television screen or computer display, pressing the photosensitive paper to the surface. Multiple light sources or exposing with multiple flashes of light, or moving the light source during exposure, projecting shadows from a low-angle light, and using successive exposures while moving, removing or adding shadows, will produce multiple shadows of varying quality.[39]

List of notable photographers using photograms

- Markus Amm[41]

- Anna Atkins[42]

- Walead Beshty[43][44]

- Christopher Bucklow[45]

- Kate Cordsen[46][47]

- Olive Cotton[48]

- Susan Derges[49]

- Michael Flomen[50][51]

- Adam Fuss[52]

- Heinz Hajek-Halke[53][54]

- Raoul Hausmann[55][56]

- John Herschel[57][58]

- Edmund Kesting[59]

- Len Lye[60][61]

- László Moholy-Nagy[62]

- Alice Lex-Nerlinger[63]

- Floris Michael Neusüss

- Anne Noble[2][64]

- Andrzej Pawlowski[65][66]

- Pablo Picasso[67]

- Man Ray

- Alexander Rodchenko[68][69]

- Theodore Roszak[70][71][72]

- Christian Schad[73][74][75][76]

- Greg Stimac[77]

- August Strindberg[78][79][80][81][82]

- Jean-Pierre Sudre[83]

- Kunié Sugiura[84]

- Henry Fox Talbot[85][86][87][88]

- Mikhail Tarkhanov[89]

- Elsa Thiemann[90]

- Luigi Veronesi[91][92][93][94]

- Kurt Wendlandt

- Nancy Wilson-Pajic[95]

- Keith Carter[96]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Photogram. |

- Luminogram: photogram using light only with no objects

- Schlieren photography: light is focused with a lens or mirror and a knife edge is placed at the focal point to create graduated shadows of flow and waves in otherwise transparent media like air, water, or glass

- Shadowgraph: like Schlieren photography, but without the knife-edge, reveals non-uniformities in transparent media

- Chemigram: camera-less technique using photographic (and other) chemistry with light

- Neues Sehen: László Moholy-Nagy's 'New Vision' photography movement

- Cliche-verre: photographic printing technique using glass plates and light-sensitive paper

- Drawn-on-film animation: cliche-verre technique in which movie film emulsion is scratched and drawn frame-by-frame

- Cyanotype

- Cyanography

References

- Langford, Michael (1999). Basic Photography (7th ed.). Oxford: Focal Press. ISBN 0-240-51592-7.

- Batchen, Geoffrey (2016), Batchen, Geoffrey (ed.), Emanations : the art of the cameraless photograph, DelMonico Books, ISBN 978-3-7913-6646-3

- Barnes, Martin; Neusüss, Floris Michael; Cordier, Pierre; Derges, Susan; Fabian Miller, Garry; Fuss, Adam (2012), Shadow catchers : camera-less photography (Rev. and expanded ed.), London, New York: Merrell / Victoria and Albert Museum, ISBN 978-1-85894-592-7

- Barnes, Martin (2018), Cameraless photography, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-48036-6

- According to Alexandra Matzner in Christian Schad 1895-1982 Retrospectief issued by the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (2009), ISBN 978-3-87909-974-0, p. 216, Schad was the first artist to use the photogram technique, developed by William Henry Fox Talbot. The photogram was applied by Man Ray, Moholy-Nagy and Chargesheimer after its introduction by Christian Schad, according to the author. However, this is not substantiated through further reference by Matzner. The Dutch catalogue was also issued in German by the Leopold Museum in Vienna (2008).

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, xxxv, 14

- Fan Pen Chen (2003), Shadow Theaters of the World, Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 62, No. 1 (2003), pp. 25-64

- Orr, Inge C. (1974). "Puppet Theatre in Asia". Asian Folklore Studies. Nanzan University. 33 (1): 69–84. doi:10.2307/1177504. JSTOR 1177504.

- Stoichiță, Victor Ieronim (1997), A short history of the shadow, Reaktion Books, ISBN 978-1-86189-000-9

- Sir Humphry Davy (1802) 'An Account of a Method of Copying Paintings Upon Glass and of Making Profiles by the Agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver, invented by T. Wedgwood Esq. In Journal of the Royal Institution

- Hannavy, John (2005), Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, Taylor & Francis Ltd, ISBN 978-0-203-94178-2

- Jones, L. (2005). From the river to the source. Artlink, 25(4), 48.

- Talbot, William Henry Fox (1844). The Pencil of Nature. London: Special Collections Department, Library, University of Glasgow. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Schaap, Robert; Tsukioka, Kōgyo; Rimer, J. Thomas; Kerlen, H. (2010), The beauty of silence : Japanese Nō and nature prints by Tsukioka Kōgyo, 1869-1927, Hotei Publishing, ISBN 978-90-04-19385-7

- Schaaf, Larry J.; Atkins, Anna (2018), Chuang, Joshua (ed.), Sun gardens : cyanotypes by Anna Atkins, The New York Public Library, ISBN 978-3-7913-5798-0

- Dickerman, Leah; Affron, Matthew (2012), Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925 : how a radical idea changed modern art, Museum of Modern Art, ISBN 978-0-87070-828-2

- Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.); Umland, Anne; Sudhalter, Adrian; Gerson, Scott (2008), Dada in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, Museum of Modern Art, ISBN 978-0-87070-668-4

- Elder, Bruce (R. Bruce) (2012), Dada, surrealism, & the cinematic effect, Lancaster: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, ISBN 978-1-55458-625-7

- Tóth, Edit (2018), Design and Visual Culture from the Bauhaus to Contemporary Art : Optical Deconstructions (1st ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-1-351-06245-9

- Hirsch, Robert (2017), Seizing the light : a social & aesthetic history of photography (Third ed.), Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, ISBN 978-1-138-94425-1

- Bergdoll, Barry; Dickerman, Leah (2009), Bauhaus 1919-1933 : workshops for modernity, London: Museum of Modern Art, ISBN 978-0-87070-758-2

- Bauhaus (1985), Bauhaus photography, Cambridge, Mass MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-13202-2

- Neusüss, Floris Michael; Barrow, Thomas F; Hagen, Charles (1994), Experimental vision : the evolution of the photogram since 1919, Roberts Rinehart Publishers in association with the Denver Art Museum, ISBN 978-1-879373-73-0

- Moholy-Nagy, Làszlò; Pénichon, Sylvie (2016), Witkovsky, Matthew S.; Eliel, Carol S.; Vail, Karole P. B. (eds.), Moholy-Nagy : future present (First ed.), Art Institute of Chicago, ISBN 978-0-86559-281-0

- Rosenblum, Naomi (1984), A world history of photography (1st ed.), Abbeville Press, ISBN 978-0-89659-438-8

- Hage, E. (2011). The Magazine as Strategy: Tristan Tzara's Dada and the Seminal Role of Dada Art Journals in the Dada Movement. The Journal of Modern Periodical Studies 2(1), 33-53. Penn State University Press

- Warren, Lynne; Warren, Lynn (2005), Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Photography, 3-Volume Set, Taylor and Francis, ISBN 978-0-203-94338-0

- Man Ray (1963), Self Portrait (1st ed.), Boston Little, Brown

- "Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky) | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- XLII esposizione internazionale d'arte la biennale di Venezia : arte e scienza, La Biennale di Venezia, 1986, ISBN 978-88-208-0331-5

- Sperone, Gian Enzo; Pelizzari, Maria Antonella; Robilant + Voena (2016), Painting in Italy, 1910s-1950s : futurism, abstraction, concrete art, Robilant + Voena, p. 148

- Miracco, Renato; Estorick Collection; Italian Cultural Institute (London, England) (2006), Italian abstraction : 1910-1960, Mazzotta, ISBN 978-88-202-1811-9

- Fuss, Adam; Tannenbaum, Barbara; Akron Art Museum; National Gallery of Victoria (1992), Adam Fuss : photograms, Akron Art Museum

- National Gallery of Victoria; Crombie, Isobel; Waite, Dianne (2003), Firstimpressions : contemporary Australian photograms, Council of Trustees of the National Gallery of Victoria

- "Abstract! 100 Years of Abstract Photography, 1917–2017". Suomen valokuvataiteen museo. 2017-04-27. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- Bargh, Peter. "Making a photogram - traditional darkroom ideas". ePhotozine.com. Magazine Publishing Ltd. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- Holter, Patra (1972), Photography without a camera, Studio Vista ; New York : Van Nostrand Reinhold, ISBN 978-0-289-70331-1

- Lange, B. (2004). Printed matter: Fotografie im/und Buch. Leipzig: Leipziger Univ-Verl.

- "Lloyd Godman index photograms". www.lloydgodman.net. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- Monash Gallery of Art (2004), The wave : Harry Nankin, Wheelers Hill, Victoria

- "Markus Amm - Artist's Profile - The Saatchi Gallery". www.saatchigallery.com. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- Brigit Katz, "How the first female photographer changed the way the world sees algae", Smithsonian, 30 May 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Appleyard, Charlotte; Salzmann, James (2012), Corporate art collections : a handbook to corporate buying, Lund Humphries / Sotheby's Institute of Art, ISBN 978-1-84822-071-3

- Furness, Rosalind (2007), Frieze Art Fair : yearbook 2007-8, New York: Frieze, p. 1928, ISBN 978-0-9553201-2-5

- Fraenkel, Jeffrey; Fraenkel Gallery (1996), Under the sun, Fraenkel Gallery, ISBN 978-1-881997-01-6

- Welling, James (2016), In Place: Contemporary Photographers Envision a Museum, ISBN 978-3-791-35366-1

- Allen, Jamie M.; McNear, Sarah (2018), The photographer in the garden (First ed.), Rochester, New York: Aperture, ISBN 978-1-59711-373-1

- Lakin, Shaune A; Cotton, Olive; Dupain, Max (2016), Max and Olive : the photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain, Canberra, A.C.T. National Gallery of Australia, ISBN 978-0-642-33462-6

- Derges, Susan; Kemp, Martin; Pereira, Sharmini (1999), Susan Derges : liquid form 1985-99, Michael Hue-Williams, ISBN 978-1-900829-07-6

- Langford, Martha (2005), Image & imagination: Mois de la photo à Montréal, Chesham: McGill-Queen's University Press, ISBN 978-0-7735-2969-4

- Shindelman, Marni; Massoni, Anne Leighton, eds. (2018), The Focal Press companion to the constructed image in contemporary photography (1st ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-29911-0

- Marien, Mary Warner (2006), Photography : a cultural history (2nd ed.), Pearson Prentice Hall, ISBN 978-0-13-221906-8

- Hajek-Halke, Heinz; Sayag, Alain; Ruetz, Michael (2002), Heinz Hajek-Halke, 1898-1983 (1st ed.), Steidl, ISBN 978-3-88243-857-4

- Hajek-Halke (1965), Abstract pictures on film : the technique of making lightgraphics, Dennis Dobson

- Neusüss, Floris Michael; Barrow, Thomas F; Hagen, Charles (1994), Experimental vision : the evolution of the photogram since 1919, Roberts Rinehart Publishers / Denver Art Museum, ISBN 978-1-879373-73-0

- Brill, Dorothée (2010), Shock and the senseless in Dada and Fluxus (1st ed.), Dartmouth College Press / University Press of New England, ISBN 978-1-58465-902-0

- Burns, Nancy Kathryn; Wilson, Kristina, eds. (2016), Cyanotypes : photography's blue period, Worcester, MA: Worcester Art Museum, ISBN 978-0-936042-06-0

- James, Christopher (2016), The book of alternative photographic processes (Third ed.), Boston: Cengage Learning, p. 234, ISBN 978-1-285-08931-7

- "Edmund Kesting. Photogram Lightbulb. 1927". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- Horrocks, Roger; Lye, Len (2001), Len Lye : a biography, Auckland University Press, ISBN 978-1-86940-247-1

- Lye, Len; Annear, Judy; Bullock, Natasha (2000), Len Lye, Art Gallery of New South Wales, ISBN 978-0-7347-6324-2

- "At first light: the most iconic camera-less photographs – in pictures", The Guardian, 27 November 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Lange, B. (2004). Printed matter: Fotografie im/und Buch. Leipzig: Leipziger Univ-Verl.

- "The global decline of the honey bee". RNZ. 2017-10-12. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- Jule, Walter (1997), Sightlines : printmaking and image culture : a collection of essays and images, University of Alberta Press, ISBN 978-0-88864-307-0

- Ronduda, Łukasz; Zeyfang, Florian (2007), 1,2,3 -- avant-gardes : film, art between experiment and archive, Warsaw: Sternberg / Centre for Contemporary Art, ISBN 978-83-85142-19-5

- Baldassari, Anne; Picasso, Pablo (1997), Picasso and photography: The dark mirror, Houston: Flammarion, ISBN 978-2-08-013646-6

- Benteler Galleries (1983), Alexander Rodchenko, Benteler Galleries

- "[Photogram with Nails (Fotogramm mit Nageln)]". The J. Paul Getty in Los Angeles. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- Venn, Beth; Weinberg, Adam D; Fraser, Kennedy (1999), Frames of reference : looking at American art, 1900-1950 : works from the Whitney Museum of American Art, London: The Museum / University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-87427-111-9

- The J. Paul Getty Museum journal, 23, J. Paul Getty Museum, 1995, p. 106, ISSN 0362-1979

- Galerie Zabriskie (2004), Zabriskie: fifty years, Ruder Finn Press, ISBN 978-1-932646-15-3

- "Christian Schad: Schadograph: 1918." MoMA. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Umland, Anne; Sudhalter, Adrian; Gerson, Scott (2008), Dada in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, Museum of Modern Art, ISBN 978-0-87070-668-4

- Geimer, Peter (2018), Inadvertent images: A history of photographic apparitions, translated by Jackson, Gerrit, The University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-47190-7

- Schad, Christian (2002), Christian Schad : peintures, dessins, schadographies, Schirmer-Mosel, ISBN 978-2-7118-4603-0

- "Review: Greg Stimac/Andrew Rafacz Gallery", New City Art, 19 June 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Strindberg, August; Hedström, Per (2001), Strindberg: Painter and photographer, Yale University Press, p. 188, ISBN 978-0-300-09187-8

- Szalczer, Eszter (2011), August Strindberg, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-41423-4

- Söderberg, R., Munch, E., Strindberg, A., & Teeland, J. (1989). Edvard Munch, August Strindberg: Fotografi som verktyg och experiment: Photography as a tool and an experiment. Stockholm: Alfabeta.

- Jäger, Gottfried; Reese, Beate; Krauss, Rolf H (2005), Konkrete fotografie [Concrete photography], Kerber Verlag, ISBN 978-3-936646-74-0

- "Traces of/by nature:August Strindberg's photographic experiments of the 1890s". IWM. 2011-02-10. Retrieved 2019-07-06.

- The Print, Time-Life International, 1972

- "Profile: Kunie Sugiura," "This is Not a Photograph", Carleton College, 2001. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Schaaf, Larry J.; Talbot, William Henry Fox (1995), Sun pictures. Catalogue seven., Photogenic drawings by William Henry Fox Talbot, Hans P. Kraus Jr, ISBN 978-0-9621096-5-2

- Schaaf, Larry J.; Talbot, William Henry Fox (2000), The photographic art of William Henry Fox Talbot, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-05000-3

- Talbot, William Henry Fox; Ollman, Arthur; Gray, Michael; McCusker, Carol (2002), First photographs: William Henry Fox Talbot and the birth of photography (1st ed.), PowerHouse Books, ISBN 978-1-57687-153-9

- Talbot, William Henry Fox; Roberts, Russell (2000), Specimens and marvels: William Henry Fox Talbot and the invention of photography (1st ed.), Aperture / National Museum of Photography, Film and Television, ISBN 978-0-89381-932-3

- "Checklist of The Judith Rothschild Foundation Gift" (PDF). Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- "Elsa Thiemann: 1929–1931 Bauhaus student", 100 Years of Bauhaus, Bauhaus Kooperation Berlin Dessau Weimar, 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Celant, Germano; Maraniello, Gianfranco (2008), Vertigo: A century of multimedia art from futurism to the Web (1st ed.), Bologna / New York: Skira / Museo d'Arte Moderna di Bologna /Rizzoli International Publications, ISBN 978-88-6130-562-5

- Veronesi, Luigi; Ballo, Guido; Fossati, Paolo; Bonini, Giuseppe; Ferrari, Giuliana (1975), Luigi Veronesi, Istituto di storia dell'arte

- Baltzer, Nanni (2015), Die Fotomontage im Faschistischen Italien: Aspekte der Propaganda Unter Mussolini, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-05-006098-9

- Lipp, Achim; Zec, Peter (1985), Mehr Licht: Künstlerhologramme und Lichtobjekte [More light], E. Kabel, ISBN 978-3-8225-0015-6

- Art/35/Basel, 16-21/6/04 : the art show, Hatje Cantz, 2004, ISBN 978-3-7757-1371-9

- Carter, Keith (2008), A certain alchemy (1st ed.), University of Texas Press, ISBN 978-0-292-71908-8