Pectus excavatum

Pectus excavatum is a structural deformity of the anterior thoracic wall in which the sternum and rib cage are shaped abnormally. This produces a caved-in or sunken appearance of the chest. It can either be present at birth or develop after puberty.

| Pectus excavatum | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Funnel chest, dented chest, sunken chest, concave chest, chest hole |

| |

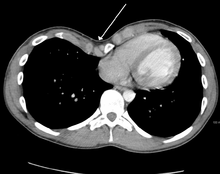

| An example of an extremely severe case of pectus excavatum. | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

Pectus excavatum can impair cardiac and respiratory function and cause pain in the chest and back.

People with the condition may experience severe negative psychosocial effects and avoid activities that expose the chest.[1]

Signs and symptoms

The hallmark of the condition is a sunken appearance of the sternum. The most common form is a cup-shaped concavity, involving the lower end of the sternum; also a broader concavity involving the upper costal cartilages is possible.[2] The lower-most ribs may protrude ("flared ribs").[3] Pectus excavatum defects may be symmetric or asymmetric.

People may also experience chest and back pain, which is usually of musculoskeletal origin.[4]

In mild cases, cardiorespiratory function is normal, although the heart can be displaced and/or rotated.[5] In severe cases, the right atrium may be compressed, mitral valve prolapse may be present, and physical capability may be limited due to base lung capacity being decreased.[6][7]

Psychological symptoms manifest with feelings of embarrassment, social anxiety, shame, limited capacity for activities and communication, negativity, intolerance, frustration, and even depression.[8]

Causes

Researchers are unsure of the cause of pectus excavatum. Some researchers take the stance that it is a congenital birth defect (not genetic) like cleft lip while others assume that there is a genetic component. A small sample size test found for at least some of the cases as 37% of individuals have an affected first degree family member.[9] As of 2012, a number of genetic markers for pectus excavatum have also been discovered.[10]

It was believed for decades that pectus excavatum is caused by an overgrowth of costal cartilage, however people with pectus excavatum actually tend to have shorter, not longer, costal cartilage relative to rib length.[11]

Pectus excavatum can be present in other conditions too, including Noonan syndrome, Marfan syndrome[12] and Loeys–Dietz syndrome as well as other connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.[13] Many children with spinal muscular atrophy develop pectus excavatum due to their diaphragmatic breathing. Pectus excavatum also occurs in about 1% of persons diagnosed with celiac disease for unknown reasons.

Pathophysiology

Physiologically, increased pressure in utero, rickets and increased traction on the sternum due to abnormalities of the diaphragm have been postulated as specific mechanisms.[9] Because the heart is located behind the sternum, and because individuals with pectus excavatum have been shown to have visible deformities of the heart seen both on radiological imaging and after autopsies, it has been hypothesized that there is impairment of function of the cardiovascular system in individuals with pectus excavatum. While some studies have demonstrated decreased cardiovascular function, no consensus has been reached based on newer physiological tests such as echocardiography of the presence or degree of impairment in cardiovascular function. However, a 2016 meta-analysis found significant evidence that surgical correction of pectus excavatum improves patient cardiac performance.[14]

Diagnosis

Pectus excavatum is initially suspected from visual examination of the anterior chest. Auscultation of the chest can reveal displaced heart beat and valve prolapse. There can be a heart murmur occurring during systole caused by proximity between the sternum and the pulmonary artery.[15] Lung sounds are usually clear yet diminished due to decreased base lung capacity.[16]

Many scales have been developed to determine the degree of deformity in the chest wall. Most of these are variants on the distance between the sternum and the spine. One such index is the Backer ratio which grades severity of deformity based on the ratio between the diameter of the vertebral body nearest to xiphosternal junction and the distance between the xiphosternal junction and the nearest vertebral body.[17] More recently the Haller index has been used based on CT scan measurements. An index over 3.25 is often defined as severe.[18] The Haller index is the ratio between the horizontal distance of the inside of the ribcage and the shortest distance between the vertebrae and sternum.[19]

Chest x-rays are also useful in the diagnosis. The chest x-ray in pectus excavatum can show an opacity in the right lung area that can be mistaken for an infiltrate (such as that seen with pneumonia).[20] Some studies also suggest that the Haller index can be calculated based on chest x-ray as opposed to CT scanning in individuals who have no limitation in their function.[21]

Pectus excavatum is differentiated from other disorders by a series of elimination of signs and symptoms. Pectus carinatum is excluded by the simple observation of a collapsing of the sternum rather than a protrusion. Kyphoscoliosis is excluded by diagnostic imaging of the spine, where in pectus excavatum the spine usually appears normal in structure.

Treatment

Pectus excavatum requires no corrective procedures in mild cases.[22] Treatment of severe cases can involve either invasive or non-invasive techniques or a combination of both. Before an operation proceeds several tests are usually performed. These include, but are not limited to, a CT scan, pulmonary function tests, and cardiology exams (such as auscultation and ECGs).[23] After a CT scan is taken, the Haller index is measured. The patient's Haller is calculated by obtaining the ratio of the transverse diameter (the horizontal distance of the inside of the ribcage) and the anteroposterior diameter (the shortest distance between the vertebrae and sternum).[24] A Haller Index of greater than 3.25 is generally considered severe, while normal chest has an index of 2.5.[19][25][26] The cardiopulmonary tests are used to determine the lung capacity and to check for heart murmurs.

Conservative treatment

The chest wall is elastic, gradually stiffening with age.[27] Non-surgical treatments have been developed that aim at gradually alleviating the pectus excavatum condition, making use of the elasticity of the chest wall, including the costal cartilages, in particular in young cases.

Exercise

Physical exercise has an important role in conservative pectus excavatum treatment though is not seen as a means to resolve the condition on its own. It is used in order to halt or slow the progression of mild or moderate excavatum conditions[28][29] and as supplementary treatment to improve a poor posture, to prevent secondary complications, and to prevent relapse after treatment.[30]

Exercises are aimed at improving posture, strengthening back and chest muscles, and enhancing exercise capacity, ideally also increasing chest expansion.[31] Pectus exercises include deep breathing and breath holding exercises,[28] as well as strength training for the back and chest muscles. Additionally, aerobic exercises to improve cardiopulmonary function are employed.[29]

Magnetic mini-mover procedure

The magnetic mini-mover procedure (3MP) is a technique used to correct pectus excavatum by using two magnets to realign the sternum with the rest of the chest and ribcage.[32] One magnet is inserted 1 cm into the patient's body on the lower end of the sternum, the other is placed externally onto a custom fitted brace. These two magnets generate around 0.04 tesla (T) in order to slowly move the sternum outwards over a number of years. The maximum magnetic field that can be applied to the body safely is around 4 T, making this technique safe from a magnetic viewpoint.[32] The 3MP technique's main advantages are that it is more cost-effective than major surgical approaches such as the Nuss procedure and it is considerably less painful postoperatively.

Its effectiveness is limited to younger children in early- to mid-puberty because older individuals have less compliant (flexible) chest walls.[33] One potential adverse interaction with other medical devices is possible inactivation of artificial pacemakers if present.

Vacuum bell

See also Vacuum Bell

An alternative to surgery, the vacuum bell, was described in 2006; the procedure is also referred to as treatment by cup suction. It consists of a bowl shaped device which fits over the caved-in area; the air is then removed by the use of a hand pump.[34] The vacuum created by this lifts the sternum upwards, lessening the severity of the deformity.[35] It has been proposed as an alternative to surgery in less severe cases.[36] Once the defect visually disappears, two additional years of use of the vacuum bell is required to make what may be a permanent correction.[37][38] The treatment, in combination with physiotherapy exercises, has been judged by some as "a promising useful alternative" to surgery provided the thorax is flexible; the duration of treatment that is required has been found to be "directly linked to age, severity and the frequency of use".[39][40] Long-term results are still lacking.[36][39][40]

The vacuum bell can also be used in preparation to surgery.[36][40]

Orthoses

Brazilian orthopedist Sydney Haje developed a non-surgical protocol for treating pectus carinatum as well as pectus excavatum. The method involves wearing a compressive orthosis and adhering to an exercise protocol.[41]

Mild cases have also reportedly been treated with corset-like orthopedic support vests and exercise.[42][43]

Thoracic surgery

There has been controversy as to the best surgical approach for correction of pectus excavatum. It is important for the surgeon to select the appropriate operative approach based on each individual's characteristics.[44] Surgical correction has been shown to repair any functional symptoms that may occur in the condition, such as respiratory problems or heart murmurs, provided that permanent damage has not already arisen from an extremely severe case.[23] Surgical correction of the pectus excavatum has been shown to significantly improve cardiovascular function;[45] there is inconclusive evidence so far as to whether it might also improve pulmonary function.[46] One of the most popular techniques for repair of pectus excavatum today is the minimally invasive operation, also known as MIRPE or Nuss technique.[47]

Ravitch technique

The Ravitch technique is an invasive surgery that was introduced in 1949[48] and developed in the 1950s. It involves creating an incision along the chest through which the cartilage is removed and the sternum detached. A small bar is inserted underneath the sternum to hold it up in the desired position. The bar is left implanted until the cartilage grows back, typically about six months. The bar is subsequently removed in a simple out-patient procedure; this technique is thus a two-stage procedure.

The Ravitch technique is not widely practiced because it is so invasive. It is more often used in older individuals, where the sternum has calcified, when the deformity is asymmetrical, or when the less invasive Nuss procedure has proven unsuccessful.[49]

Nuss procedure

In 1987, Donald Nuss, based at Children's Hospital of The King's Daughters in Norfolk, Virginia, performed the first minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum (MIRPE) [50] and presented it much later at a conference in 1997.[50][51][52]

His procedure, widely known as the Nuss procedure, involves slipping in one or more concave steel bars into the chest, underneath the sternum. The bar is flipped to a convex position so as to push outward on the sternum, correcting the deformity. The bar usually stays in the body for about two years, although many surgeons are now moving toward leaving them in for up to five years. When the bones have solidified into place, the bar is removed through outpatient surgery. Although initially designed to be performed in younger children (less than 10 years of age) whose sternum and cartilage is more flexible, there are successful series of Nuss treatment in patients well into their teens and twenties. The Nuss procedure is a two-stage procedure.

Robicsek technique

In 1965, Francis Robicsek, based at Charlotte Memorial Hospital, now named Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, North Carolina, developed the Robicsek procedure. Each time the procedure is performed, it is individually tailored based on the extent and location of the deformity in the patient. The operation begins with an incision, no more than 4–6 centimeters, to the sternum. The pectoralis major muscles are then detached from the sternum. Using the upper limit of the sternal depression as a guide, the deformed cartilages are removed one-by-one, using sharp and blunt dissection. The lower tip of the sternum is then grabbed with a towel-clip and, using blunt dissection, is freed of tissue connections with the pericardium and the pleura. The sternum is then forcefully bent forward into a corrected position. To keep the sternum elevated, a piece of mesh is placed under the mobilized sternum and sutured under moderate tension bilaterally to the stumps of the ribs. The pectoralis muscles are united in front of the sternum and the wound is closed. The Robicsek procedure is a single-stage procedure (one surgery only).[53]

The purported advantage of this technique is that it is less invasive than the Ravitch technique, but critics have suggested that the relapse rate may be high due to cartilage and bone displaying memory phenomenon.[44]

Taulinoplasty

In 2016, Carlos Bardají, a Barcelona-based pediatric surgeon, together with Lluís Cassou, a biomedical engineer, published a paper describing an extra-thoracic surgical procedure for the correction of pectus excavatum called taulinoplasty.[54] A specially designed implant and traction hardware were developed specifically for the procedure.

In taulinoplasty, a small hole is drilled into the sternum at the deepest point of defect, and a double screw is driven into the hole. Then, a stainless steel implant is placed underneath the skin on top of the sternum and ribs, centered over the double screw. Traction tools are then used to lift the sternum up by the double screw using the implant and ribs for traction. Additional screws are then used to secure the implant onto the sternum holding the sternum in the desired position. Optionally, stainless steel wire may be wrapped around the implant and ribs to further secure the implant in place.

Like the Nuss procedure, taulinoplasty requires follow-up surgery several years later to remove the implanted hardware once the sternum has permanently assumed its new position.

The implant and related hardware used in taulinoplasty is a proprietary product of Ventura Medical Technologies and is marketed as a surgical kit under the brand name Pectus UP.[55]

Taulinoplasty was developed to be an alternative to the Nuss procedure that eliminates the risks and drawbacks of entering the thorax. In particular, patients usually have shorter operating and recovery times, and less post-operative pain than with the Nuss procedure.

Plastic surgery

Implants

The implant allows pectus excavatum to be treated from a purely morphological perspective. Today it is used as a benchmark procedure as it is simple, reliable, and minimally intrusive while offering aesthetically-pleasing results.[56] This procedure does not, however, claim to correct existing cardiac and respiratory problems which, in very rare cases, can be triggered by the pectus excavatum condition. For female sufferers, the potential resulting breast asymmetry can be partially or completely corrected by this procedure.[57]

The process of creating a plaster-cast model, directly on the skin of the patient's thorax, can be used in the design of the implants. The evolution of medical imaging and CAD (computer-aided design)[58] now allows customised 3D implants to be designed directly from the ribcage, therefore being much more precise, easier to place sub-pectorally and perfectly adapted to the shape of each patient.[59] The implants are made of medical silicon rubber which is age-resistant and unbreakable (different to the silicon gel used in breast implants). They will last for life (apart from the case of adverse reactions) and are not visible externally.

The surgery is performed under general anesthesia and takes about an hour. The surgeon makes an incision of approximately seven centimetres, prepares the customised space in the chest, inserts the implant deep beneath the muscle, then closes the incision. Post-operative hospitalization is typically around three days.

The recovery after the surgery typically requires only mild pain relief. Post-operatively, a surgical dressing is required for several days and compression vest for a month following the procedure. A check-up appointment is carried out after a week for puncture of seroma. If the surgery has minimal complications, the patient can resume normal activities quickly, returning to work after 15 days and participating in any sporting activities after three months.

Lipofilling

The "lipofilling" technique consists of sucking fat from the patient using a syringe with a large gauge needle (usually from the abdomen or the outer thighs), then after centrifugation, the fat cells are re-injected beneath the skin into whichever hollow it is needed to fill. This technique is primarily used to correct small defects which may persist after conventional surgical treatment.

Epidemiology

Pectus excavatum occurs in an estimated 1 in 150 to 1 in 1000 births, with male predominance (male-to-female ratio of 3:1). In 35% to 45% of cases family members are affected.[16][60]

Etymology

Pectus excavatum is from Latin meaning hollowed chest.[61] It is sometimes referred to as sunken chest syndrome, cobbler's chest or funnel chest.[62][63]

Society

American Olympic swimmer Cody Miller (born 1992) opted not to have treatment for pectus excavatum, even though it limited his lung capacity. He earned a gold medal in 2016.[64][65][66] Professional wrestler Kofi Kingston has not opted for surgery, or ever publicly discussed it. He won his first WWE Championship at WrestleMania 35 after being in the company for 12 years.[67]

In animals

Pectus excavatum is also known to occur in animals, e.g. the Munchkin breed of cat.[68] Some procedures used to treat the condition in animals have not been used in human treatments, such as the use of a cast with sutures wrapped around the sternum and the use of internal and external splints.[69][70] These techniques are generally used in immature animals with flexible cartilage.[71]

See also

References

- "Pectus excavatum". MedLine Plus Medical Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health. 2007-11-12.

- Blanco FC, Elliott ST, Sandler AD (2011). "Management of congenital chest wall deformities". Seminars in Plastic Surgery (Review). 25 (1): 107–16. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1275177. PMC 3140238. PMID 22294949.

- See for example Bosgraaf RP, Aronson DC (2010). "Treatment of flaring of the costal arch after the minimally invasive pectus excavatum repair (Nuss procedure) in children". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 45 (9): 1904–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.05.037. PMID 20850643.

- "Pectus Excavatum Clinical Presentation: History". Medscape. 30 June 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- Fokin AA, Steuerwald NM, Ahrens WA, Allen KE (2009). "Anatomical, histologic, and genetic characteristics of congenital chest wall deformities". Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (Review). 21 (1): 44–57. doi:10.1053/j.semtcvs.2009.03.001. PMID 19632563.

- "Cardiopulmonary Manifestations of Pectus Excavatum". Medscape.(subscription required)

- Jaroszewski, Dawn E.; Warsame, Tahlil A.; Chandrasekaran, Krishnaswamy; Chaliki, Hari (December 2011). "Right Ventricular Compression Observed in Echocardiography from Pectus Excavatum Deformity". Journal of Cardiovascular Ultrasound. 19 (4): 192–195. doi:10.4250/jcu.2011.19.4.192. ISSN 1975-4612. PMC 3259543. PMID 22259662.

- Brandon, Mike (2016-02-04). "Orthopedic approach to pectus deformities: 32 years of studies". Pectus Excavatum Info. Pediatric Orthopedist and Physiatrist, Orthopectus Clinical Center and Asa Norte Regional Hospital. 2Doctor in Orthopedics, School of Medicine, University de Sāo Paulo, Ribeirāo Preto, SP. Pediatric Orthopedist, Orthopectus Clinical Center. Preceptor, Adult Foot and Pediatric Orthopedics, Federal District Hospital, Brasilia, DF. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- Shamberger RC (1996). "Congenital chest wall deformities". Current Problems in Surgery (Review). 33 (6): 469–542. doi:10.1016/S0011-3840(96)80005-0. PMID 8641129.

- Dean C, Etienne D, Hindson D, Matusz P, Tubbs RS, Loukas M (2012). "Pectus excavatum (funnel chest): a historical and current prospective". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 34 (7): 573–9. doi:10.1007/s00276-012-0938-7. PMID 22323132.

- Eisinger, Robert S.; Harris, Travis; Rajderkar, Dhanashree A.; Islam, Saleem (2019-03-01). "Against the Overgrowth Hypothesis: Shorter Costal Cartilage Lengths in Pectus Excavatum". Journal of Surgical Research. 235: 93–97. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2018.09.080. ISSN 0022-4804. PMID 30691856.

- "eMedicine — Marfan Syndrome". Harold Chen. 2018-05-23.

- Creswick HA1, Stacey MW, Kelly RE Jr, Gustin T, Nuss D, Harvey H, Goretsky MJ, Vasser E, Welch JC, Mitchell K, Proud VK (October 2006). "Family study of the inheritance of pectus excavatum". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 41 (10): 1699–703. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.05.071. PMID 17011272.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Maagaard M, Heiberg J (2016). "Improved cardiac function and exercise capacity following correction of pectus excavatum: a review of current literature". Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery (Review). 5 (5): 485–492. doi:10.21037/acs.2016.09.03. PMC 5056930. PMID 27747182.

- Guller B, Hable K (1974). "Cardiac findings in pectus excavatum in children: review and differential diagnosis". Chest. 66 (2): 165–71. doi:10.1378/chest.66.2.165. PMID 4850886. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08.

- "eMedicine — Pectus Excavatum". Andre Hebra. 2018-09-18.

- BACKER OG, BRUNNER S, LARSEN V (1961). "The surgical treatment of funnel chest. Initial and follow-up results". Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica. 121: 253–61. PMID 13685690.

- Jeannette Diana-Zerpa; Nancy Thacz Browne; Laura M. Flanigan; Carmel A. McComiskey; Pam Pieper (2006). Nursing Care of the Pediatric Surgical Patient (Browne, Nursing Care of the Pediatric Surgical Patient). Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-7637-4052-8.

- Haller JA, Kramer SS, Lietman SA (1987). "Use of CT scans in selection of patients for pectus excavatum surgery: a preliminary report". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 22 (10): 904–6. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(87)80585-7. PMID 3681619.

- Hoeffel JC, Winants D, Marcon F, Worms AM (1990). "Radioopacity of the right paracardiac lung field due to pectus excavatum (funnel chest)". Rontgenblatter. 43 (7): 298–300. PMID 2392647.

- Mueller C, Saint-Vil D, Bouchard S (2008). "Chest x-ray as a primary modality for preoperative imaging of pectus excavatum". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 43 (1): 71–3. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.09.023. PMID 18206458.

- Klingman, RM (2011). Nelson Texbook of Pediatrics. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

- Crump HW (1992). "Pectus excavatum". Am Fam Physician (Review). 46 (1): 173–9. PMID 1621629.

- "How the Haller is measured. Departament of Cardiology and Pulmonology of the Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo – Thoracic Surgery Sector" (PDF).

- "The Nuss procedure for pectus excavatum correction | AORN Journal". Barbara Swoveland, Clare Medrick, Marilyn Kirsh, Kevin G. Thompson, Nussm Donald. 2001.

- "Pectus Excavatum overview" (PDF). CIGNA.

- "Lung elasticity, thorax and age". Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- Peter Mattei (15 February 2011). Fundamentals of Pediatric Surgery. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 315. ISBN 978-1-4419-6643-8.

- Anton H. Schwabegger (15 September 2011). Congenital Thoracic Wall Deformities: Diagnosis, Therapy and Current Developments. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 118. ISBN 978-3-211-99138-1.

- George W. Holcomb III; Jerry D Murphy; Daniel J Ostlie (31 January 2014). Ashcraft's Pediatric Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-323-18736-7.

- Lewis Spitz; Arnold Coran (21 May 2013). Operative Pediatric Surgery, Seventh Edition. CRC Press. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-4441-1715-8.

- Harrison MR, Estefan-Ventura D, et al. (January 2007). "Magnetic Mini-Mover Procedure for pectus excavatum: I. Development, design, and simulations for feasibility and safety" (PDF). Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 42 (1): 81–85. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.09.042. PMID 17208545. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- Harrison, MR; Michael R. Harrison; Kelly D. Gonzales; Barbara J. Bratton; Darrell Christensen; Patrick F. Curran; Richard Fechter; Shinjiro Hirose (January 2012). "Magnetic mini-mover procedure for pectus excavatum III: safety and efficacy in a Food and Drug Administration-sponsored clinical trial". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 47 (1): 154–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.10.039. PMID 22244409.

- chkd, Norfolk, VA: Children's Hospital of the King's Daughters, archived from the original on 2013-10-11

- Haecker, FM; Mayr J (April 2006). "The vacuum bell for treatment of pectus excavatum: an alternative to surgical correction?". European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 29 (4): 557–561. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.01.025. PMID 16473516.

- Brochhausen C, Turial S, Müller FK, Schmitt VH, Coerdt W, Wihlm JM, Schier F, Kirkpatrick CJ (2012). "Pectus excavatum: history, hypotheses and treatment options". Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery (Review). 14 (6): 801–6. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivs045. PMC 3352718. PMID 22394989.

- Non-surgical sunken chest treatment device may eliminate surgery, Mass Device, November 2012

- Raver-Lampman (November 2012), First patients in US receive non-surgical device of sunken chest syndrome, AAAS

- Lopez M, Patoir A, Costes F, Varlet F, Barthelemy JC, Tiffet O (2016). "Preliminary study of efficacy of cup suction in the correction of typical pectus excavatum". Journal of Pediatric Surgery (Review). 51 (1): 183–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.10.003. PMID 26526206.

- Haecker FM, Sesia S (2016). "Non-surgical treatment of pectus excavatum". Journal of Visualized Surgery. 2: 63. doi:10.21037/jovs.2016.03.14. PMC 5638434. PMID 29078491.

- Haje SA, de Podestá Haje D (2009). "Orthopedic Approach to Pectus Deformities: 32 Years of Studies". Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia. 44 (3): 191–8. doi:10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30067-7. PMC 4783668. PMID 27004171.

- "LaceIT PE Brace". Advanced Orthotic Designs, Inc.

- "Orthopectus". Dr. Sydney A. Haje, Ortopedista.

- Robicsek, Hebra (2009). "To Nuss or not to Nuss? Two opposing views". Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 21 (1): 85–88. doi:10.1053/j.semtcvs.2009.03.007. PMID 19632567.

- Malek MH, Berger DE, Housh TJ, Marelich WD, Coburn JW, Beck TW (2006). "Cardiovascular function following surgical repair of pectus excavatum: a metaanalysis". Chest (Meta-Analysis). 130 (2): 506–16. doi:10.1378/chest.130.2.506. PMID 16899852.

- Malek MH, Berger DE, Marelich WD, Coburn JW, Beck TW, Housh TJ (2006). "Pulmonary function following surgical repair of pectus excavatum: a meta-analysis". European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (Meta-Analysis). 30 (4): 637–43. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.004. PMID 16901712.

- Hebra A (2009). "Minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum". Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg (Review). 21 (1): 76–84. doi:10.1053/j.semtcvs.2009.04.005. PMC 5637818. PMID 19632566.

- Ravitch MM (April 1949). "The Operative Treatment of Pectus Excavatum". Ann Surg. 129 (4): 429–44. doi:10.1097/00000658-194904000-00002. PMC 1514034. PMID 17859324.

- Theresa D. Luu MD (November 2009). "Surgery for Recurrent Pectus Deformities". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 88 (5): 1627–1631. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.06.008. PMID 19853122.

- Adam J. Białas; Bogumiła Kempińska-Mirosławska (2013). "Minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum (the Nuss procedure) in Poland and worldwide – a summary of 25 years of history" (PDF). Kardiochirurgia i Torakochirurgia Polska. 10 (1): 42–47. doi:10.5114/kitp.2013.34304. Retrieved 13 April 2016.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Nuss D, Kelly RE Jr, Croitoru DP, Katz ME (April 1998). "A 10-year review of a minimally invasive technique for the correction of pectus excavatum". J Pediatr Surg. 33 (4): 545–52. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(98)90314-1. PMID 9574749.

- Pilegaard, HK; Licht PB (February 2008). "Early results following the Nuss operation for pectus excavatum—a single-institution experience of 383 patients". Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 7 (1): 54–57. doi:10.1510/icvts.2007.160937. PMID 17951271. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- Robiscek, Francis. "Marlex Mesh Support For The Correction Of Very Severe And Recurrent Pectus Excavatum". 26 (1): 80–83. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bardají, Carlos; Cassou, Lluís (12 September 2016). "Taulinoplasty: the traction technique—a new extrathoracic repair for pectus excavatum". Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 5 (5): 519–522. doi:10.21037/acs.2016.09.07. PMC 5056940. PMID 27747186.

- "Pectus UP surgery kit, the solution for Pectus Excavatum" (PDF). Ventura Medical Technologies. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- André, M. Dahan, E. Bozonnet, I. Garrido, J.-L. Grolleau, J.-P. Chavoin; Pectus excavatum : correction par la technique de comblement avec mise en place d’une prothèse en silicone sur mesure en position rétromusculaire profonde; Encycl Méd Chir, Elsevier Masson SAS - Techniques chirurgicales - Chirurgie plastique reconstructrice et esthétique, 45-671, Techniques chirurgicales - Thorax, 42-480, 2010.

- Ho Quoc Ch, Chaput B, Garrido I, André A, Grolleau JL, Chavoin JP; Management of breast asymmetry associated with primary funnel chest; Ann Chir Plast Esthet. Elsevier Masson SAS; 2012 Aug 8:1–6.

- "Pectus Excavatum & Poland Syndrome treatment I AnatomikModeling".

- J-P. Chavoin, A.André, E.Bozonnet, A.Teisseyre, J..Arrue, B. Moreno, D. Glangloff, J-L. Grolleau, I.Garrido; Mammary implant selection or chest implants fabrication with computer help; Ann.de chirurgie plastique esthétique (2010) 55,471-480.

- "Pectus Excavatum: Frequently Asked Questions: Surgery: UI Health Topics". Harold M. Burkhart and Joan Ricks-McGillin.

- chief lexicographer: Douglas M. Anderson (2003). "Pectus Excavatum". Dorland's Medical Dictionary (28 ed.). Philadelphia, Penns.: Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-0146-5. Archived from the original on 2009-01-21. Retrieved 2017-05-24.

- "Pectus Excavatum".

- Spence, Roy A. J.; Patrick J. Morrison (2005). Genetics for Surgeons. Remedica Publishing. ISBN 978-1-901346-69-5.

- {{ |url= http://www.raredr.com/news/rare-disease-rio-cm}}

- Cody Miller Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine – National Team swimmer profile at USASwimming.org

- Woods, David (27 June 2016). "Cody Miller is IU's first U.S. Olympic swimmer in 40 years". Indianapolis Star. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- {{|url= https://www.distractify.com/p/kofi-kingston-chest-accident |accessdate=11 August 2019|publisher=Distractify|date=23 July 2019}}

- "Genetic Anomalies of Cats".

- Fossum, TW; Boudrieau RJ; Hobson HP; Rudy RL (1989). "Surgical correction of pectus excavatum, using external splintage in two dogs and a cat". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 195 (1): 91–7. PMID 2759902.

- Risselada M, de Rooster H, Liuti T, Polis I, van Bree H (2006). "Use of internal splinting to realign a noncompliant sternum in a cat with pectus excavatum". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 228 (7): 1047–52. doi:10.2460/javma.228.7.1047. PMID 16579783.

- McAnulty JF, Harvey CE (1989). "Repair of pectus excavatum by percutaneous suturing and temporary external coaptation in a kitten". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 194 (8): 1065–7. PMID 2651373.

Further reading

- Tocchioni F, Ghionzoli M, Messineo A, Romagnoli P (2013). "Pectus excavatum and heritable disorders of the connective tissue". Pediatric Reports (Review). 5 (3): e15. doi:10.4081/pr.2013.e15. PMC 3812532. PMID 24198927.

- Jaroszewski D, Notrica D, McMahon L, Steidley DE, Deschamps C (2010). "Current management of pectus excavatum: a review and update of therapy and treatment recommendations". Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine (Review). 23 (2): 230–9. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2010.02.090234. PMID 20207934.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pectus excavatum. |

| Look up pectus in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |