Genu valgum

Genu valgum, commonly called "knock-knee", is a condition in which the knees angle in and touch each other when the legs are straightened. Individuals with severe valgus deformities are typically unable to touch their feet together while simultaneously straightening the legs. The term originates from the Latin genu, 'knee', and valgus which actually means 'bent outwards', but in this case, it is used to describe the distal portion of the knee joint which bends outwards and thus the proximal portion seems to be bent inwards. For citation and more information on uses of the words Valgus and Varus, please visit the internal link to -varus.

| Genu valgum | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Knock knee |

| |

| A very severe case of genu valgum of the left knee following bone cancer treatment | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Mild genu valgum is diagnosed when a person standing upright with the feet touching also shows the knees touching. It can be seen in children from ages 2 to 5, and is often corrected naturally as children grow. However, the condition may continue or worsen with age, particularly when it is the result of a disease, such as rickets. Idiopathic genu valgum is a form that is either congenital or has no known cause.

Other systemic conditions may be associated, such as Schnyder crystalline corneal dystrophy, an autosomal dominant condition frequently reported with hyperlipidemia.

Cause

Genu valgum can arise from a variety of causes including nutritional, genetic, traumatic, idiopathic or physiologic and infectious.[1]

Rickets

Nutritional rickets is an important cause of childhood genu valgum or knock knees in some parts of the world. Nutritional rickets arises from unhealthy life style habits as insufficient exposure to sun light which is the main source of vitamin D. Insufficient dietary intake of calcium is another contributing factor.[2][3] Similarly,genu valgum may arise from rickets caused by genetic abnormalities, called resistant forms rickets.

Osteochondrodysplasia

Osteochondrodysplasia are a variable group of genetic bone diseases or genetic skeletal dysplasias that present with generalized bone deformities involving all extremities and the spine. Genu valgum or knock knees is one of the known skeletal manifestations of Osteochondrodysplasias. A complete bone X-ray survey is mandatory to reach a definitive diagnosis.[4]

Trauma

Toxic

Excess of Cadmium can lead to osteomyelasis. Cadmium can produce toxic effect to the bones, it leads to Deficiency of Vitamin D, which causes weakening of Bones, fractures and permanent deformation. Itai-itai disease in Japan was most appropriate examples of cadmium toxicity.

Diagnostic

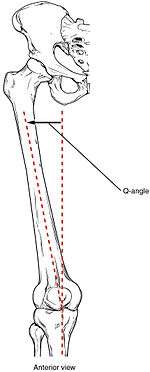

The degree of genu valgum can clinically be estimated by the Q angle, which is the angle formed by a line drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine through the center of the patella and a line drawn from the center of the patella to the center of the tibial tubercle. In women, the Q angle should be less than 22 degrees with the knee in extension and less than 9 degrees with the knee in 90 degrees of flexion. In men, the Q angle should be less than 18 degrees with the knee in extension and less than 8 degrees with the knee in 90 degrees of flexion. A typical Q angle is 12 degrees for men and 17 degrees for women.[5]

Radiography

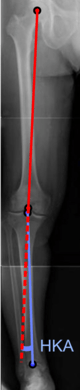

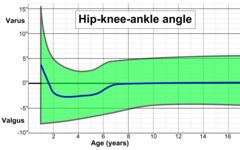

On projectional radiography, the degree of varus or valgus deformity can be quantified by the hip-knee-ankle angle,[6] which is an angle between the femoral mechanical axis and the center of the ankle joint.[7] It is normally between 1.0° and 1.5° of varus in adults.[8] Normal ranges are different in children.[9]

Hip-knee-ankle angle.

Hip-knee-ankle angle. Hip-knee-ankle angle by age, with 95% prediction interval.[9]

Hip-knee-ankle angle by age, with 95% prediction interval.[9]

Treatment

The treatment of genu valgum in children depends on the underlying cause. Developmenta--also known as idiopathic--genu valgum is usually self-limiting and resolves during childhood. Genu valgum secondary to nutritional rickets is typically treated with lifestyle modifications in the form of adequate sun exposure to ensure receiving the daily requirements of vitamin D, as well as a calcium-rich diet. Calcium and vitamin D supplementations may be used. If the deformity does not resolve despite the above conservative treatment and the deformity is severe, causing gait impairment, surgery can be an option. Typically, guided growth surgery is used to straighten the deformed bone.[3] Genu valgum arising from osteochondrodysplasia[4] usually needs repeated guided growth surgical interventions.[10] Genu valgum secondary to trauma depends on the degree of physical damage. And usually limb reconstruction procedures are needed, especially if trauma occurs in the early years of life where the anticipated remaining longitudinal bone growth is great.

The treatment of genu valgum in adults depends on the underlying cause and the degree of joint involvement namely arthritis. Bone corrective osteotomies and prosthetic joint replacement may be used depending upon the patient's age and symptomatology in terms of pain and functional impairment. Weight loss and substitution of high-impact for low-impact exercise can help slow progression of the condition. With every step, the patient's weight places a distortion on the knee toward a knocked knee position, and the effect is increased with increased angle or increased weight. Even in the normal knee position, the femurs function at an angle because they connect to the hip girdle at points much further apart than they connect at the knees.

Working with a physical medicine specialist such as a physiatrist, or a physiotherapist may assist a patient learning how to improve outcomes and use the leg muscles properly to support the bone structures. Alternative or complementary treatments may include certain procedures from Iyengar Yoga or the Feldenkrais Method.

See also

- Genu varum (bow-legs)

- Genu recurvatum (back knee)

- Knee pain

- Knee osteoarthritis

References

- NHS (January 2016). "Knock Knees".

- Creo, AL; Thacher, TD; Pettifor, JM; Strand, MA; Fischer, PR (6 December 2016). "Nutritional rickets around the world: an update. Paediatr Int Child Health". Paediatr Int Child Health. 37 (2). doi:10.1080/20469047.2016.1248170.

- EL-Sobky, TA; Samir, S; Baraka, MM; Fayyad, TA; Mahran, MA; Aly, AS; Amen, J; Mahmoud, S (1 January 2020). "Growth modulation for knee coronal plane deformities in children with nutritional rickets: A prospective series with treatment algorithm". JAAOS: Global Research and Reviews. 4 (1). doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-19-00009.

- EL-Sobky, TA; Shawky, RM; Sakr, HM; Elsayed, SM; Elsayed, NS; Ragheb, SG; Gamal, R (15 November 2017). "A systematized approach to radiographic assessment of commonly seen genetic bone diseases in children: A pictorial review". J Musculoskelet Surg Res. 1 (2): 25. doi:10.4103/jmsr.jmsr_28_17.

- Mohammad-Jafar Emami, Mohammad-Hossein Ghahramani, Farzad Abdinejad and Hamid Namazi (January 2007). "Q-angle: an invaluable parameter for evaluation of anterior knee pain". Archives of Iranian Medicine. 10 (1): 24–26. PMID 17198449.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- W-Dahl, Annette; Toksvig-Larsen, Sören; Roos, Ewa M (2009). "Association between knee alignment and knee pain in patients surgically treated for medial knee osteoarthritis by high tibial osteotomy. A one year follow-up study". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 10 (1): 154. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-10-154. ISSN 1471-2474. PMC 2796991. PMID 19995425.

- Cherian, Jeffrey J.; Kapadia, Bhaveen H.; Banerjee, Samik; Jauregui, Julio J.; Issa, Kimona; Mont, Michael A. (2014). "Mechanical, Anatomical, and Kinematic Axis in TKA: Concepts and Practical Applications". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 7 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1007/s12178-014-9218-y. ISSN 1935-973X. PMC 4092202. PMID 24671469.

- Sheehy, L.; Felson, D.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, J.; Lam, Y.-M.; Segal, N.; Lynch, J.; Cooke, T.D.V. (2011). "Does measurement of the anatomic axis consistently predict hip-knee-ankle angle (HKA) for knee alignment studies in osteoarthritis? Analysis of long limb radiographs from the multicenter osteoarthritis (MOST) study". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 19 (1): 58–64. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2010.09.011. ISSN 1063-4584. PMC 3038654. PMID 20950695.

- Sabharwal, Sanjeev; Zhao, Caixia (2009). "The Hip-Knee-Ankle Angle in Children: Reference Values Based on a Full-Length Standing Radiograph". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, American Volume. 91 (10): 2461–2468. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00015. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 19797583.

- Journeau, P (25 October 2019). "Update on guided growth concepts around the knee in children". Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. S1877-0568 (19). doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2019.04.025.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/20622193/ Cadmium lauded deficiency