Mitral valve prolapse

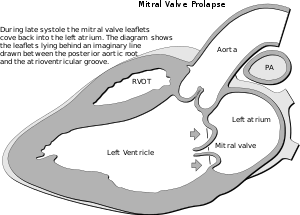

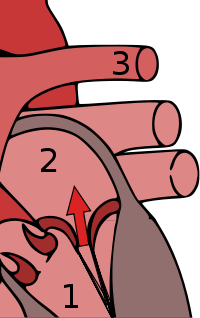

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is a valvular heart disease characterized by the displacement of an abnormally thickened mitral valve leaflet into the left atrium during systole.[2] It is the primary form of myxomatous degeneration of the valve. There are various types of MVP, broadly classified as classic and nonclassic. In severe cases of classic MVP, complications include mitral regurgitation, infective endocarditis, congestive heart failure, and, in rare circumstances, cardiac arrest.

| Mitral valve prolapse | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Floppy mitral valve syndrome, systolic click murmur syndrome, billowing mitral leaflet, Barlow's syndrome[1] |

| |

| In mitral valve prolapse, the leaflets of the mitral valve prolapse back into the left atrium. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

The diagnosis of MVP depends upon echocardiography, which uses ultrasound to visualize the mitral valve. MVP is estimated to affect 2–3% of the population.[2]

The condition was first described by John Brereton Barlow in 1966.[1] It was subsequently termed mitral valve prolapse by J. Michael Criley.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Murmur

Upon auscultation of an individual with mitral valve prolapse, a mid-systolic click, followed by a late systolic murmur heard best at the apex, is common. The length of the murmur signifies the time period over which blood is leaking back into the left atrium, known as regurgitation. A murmur that lasts throughout the whole of systole is known as a holo-systolic murmur. A murmur that is mid to late systolic, although typically associated with less regurgitation, can still be associated with significant hemodynamic consequences.[4]

In contrast to most other heart murmurs, the murmur of mitral valve prolapse is accentuated by standing and valsalva maneuver (earlier systolic click and longer murmur) and diminished with squatting (later systolic click and shorter murmur). The only other heart murmur that follows this pattern is the murmur of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A MVP murmur can be distinguished from a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy murmur by the presence of a mid-systolic click which is virtually diagnostic of MVP. The handgrip maneuver diminishes the murmur of an MVP and the murmur of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The handgrip maneuver also diminishes the duration of the murmur and delays the timing of the mid-systolic click.[5]

Both valsalva maneuver and standing decrease venous return to the heart thereby decreasing left ventricular diastolic filling (preload) and causing more laxity on the chordae tendineae. This allows the mitral valve to prolapse earlier in systole, leading to an earlier systolic click (i.e. closer to S1), and a longer murmur.

Mitral valve prolapse syndrome

Historically, the term mitral valve prolapse syndrome has been applied to MVP associated with palpitations, atypical precordial pain, dyspnea on exertion, low body mass index, and electrocardiogram abnormalities (ventricular tachycardia), syncope, low blood pressure, headaches, lightheadedness, and other signs suggestive of autonomic nervous system dysfunction (dysautonomia).[2]

Mitral regurgitation

Mitral valve prolapse is frequently associated with mild mitral regurgitation,[6] where blood aberrantly flows from the left ventricle into the left atrium during systole. In the United States, MVP is the most common cause of severe, non-ischemic mitral regurgitation.[2] This is occasionally due to rupture of the chordae tendineae that support the mitral valve.[5]

Risk factors

MVP may occur with greater frequency in individuals with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome[7] or polycystic kidney disease.[8] Other risk factors include Graves disease and chest wall deformities such as pectus excavatum.[9] For unknown reasons, MVP patients tend to have a low body mass index (BMI) and are typically leaner than individuals without MVP.[10][11]

Rheumatic fever is common worldwide and responsible for many cases of damaged heart valves. Chronic rheumatic heart disease is characterized by repeated inflammation with fibrinous resolution. The cardinal anatomic changes of the valve include leaflet thickening, commissural fusion, and shortening and thickening of the tendinous cords.[12] The recurrence of rheumatic fever is relatively common in the absence of maintenance of low dose antibiotics, especially during the first three to five years after the first episode. Heart complications may be long-term and severe, particularly if valves are involved. Rheumatic fever, since the advent of routine penicillin administration for Strep throat, has become less common in developed countries. In the older generation and in much of the less-developed world, valvular disease (including mitral valve prolapse, reinfection in the form of valvular endocarditis, and valve rupture) from undertreated rheumatic fever continues to be a problem.[13]

In an Indian hospital between 2004 and 2005, 4 of 24 endocarditis patients failed to demonstrate classic vegetations. All had rheumatic heart disease (RHD) and presented with prolonged fever. All had severe eccentric mitral regurgitation (MR). (One had severe aortic regurgitation (AR) also.) One had flail posterior mitral leaflet (PML).[14]

The mitral valve, so named because of its resemblance to a bishop's mitre, is the heart valve that prevents the backflow of blood from the left ventricle into the left atrium of the heart. It is composed of two leaflets, one anterior and one posterior, that close when the left ventricle contracts.

Each leaflet is composed of three layers of tissue: the atrialis, fibrosa, and spongiosa. Patients with classic mitral valve prolapse have excess connective tissue that thickens the spongiosa and separates collagen bundles in the fibrosa. This is due to an excess of dermatan sulfate, a glycosaminoglycan. This weakens the leaflets and adjacent tissue, resulting in increased leaflet area and elongation of the chordae tendineae. Elongation of the chordae tendineae often causes rupture, commonly to the chordae attached to the posterior leaflet. Advanced lesions—also commonly involving the posterior leaflet—lead to leaflet folding, inversion, and displacement toward the left atrium.[10]

Genetics

An association with primary cilia defects has been reported.[15] The mutations were found in the Zinc finger protein DZIP1 (DZIP1) gene.

Diagnosis

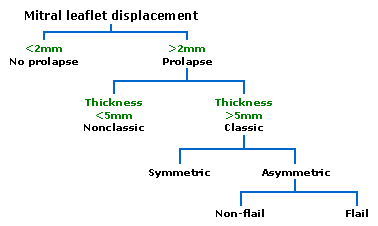

Echocardiography is the most useful method of diagnosing a prolapsed mitral valve. Two- and three-dimensional echocardiography are particularly valuable as they allow visualization of the mitral leaflets relative to the mitral annulus. This allows measurement of the leaflet thickness and their displacement relative to the annulus. Thickening of the mitral leaflets >5 mm and leaflet displacement >2 mm indicates classic mitral valve prolapse.[10]

Prolapsed mitral valves are classified into several subtypes, based on leaflet thickness, type of connection to the mitral annulus, and concavity. Subtypes can be described as classic, nonclassic, symmetric, asymmetric, flail, or non-flail.[10]

All measurements below refer to adult patients; applying them to children may be misleading.

Classic versus nonclassic

Prolapse occurs when the mitral valve leaflets are displaced more than 2 mm above the mitral annulus high points. The condition can be further divided into classic and nonclassic subtypes based on the thickness of the mitral valve leaflets: up to 5 mm is considered nonclassic, while anything beyond 5 mm is considered classic MVP.[10]

Symmetric versus asymmetric

Classical prolapse may be subdivided into symmetric and asymmetric, referring to the point at which leaflet tips join the mitral annulus. In symmetric coaptation, leaflet tips meet at a common point on the annulus. Asymmetric coaptation is marked by one leaflet displaced toward the atrium with respect to the other. Patients with asymmetric prolapse are susceptible to severe deterioration of the mitral valve, with the possible rupture of the chordae tendineae and the development of a flail leaflet.[10]

Flail versus non-flail

Asymmetric prolapse is further subdivided into flail and non-flail. Flail prolapse occurs when a leaflet tip turns outward, becoming concave toward the left atrium, causing the deterioration of the mitral valve. The severity of flail leaflet varies, ranging from tip eversion to chordal rupture. Dissociation of leaflet and chordae tendineae provides for unrestricted motion of the leaflet (hence "flail leaflet"). Thus patients with flail leaflets have a higher prevalence of mitral regurgitation than those with the non-flail subtype.[10]

Treatment

Individuals with mitral valve prolapse, particularly those without symptoms, often require no treatment.[16] Those with mitral valve prolapse and symptoms of dysautonomia (palpitations, chest pain) may benefit from beta-blockers (e.g., propranolol). People with prior stroke or atrial fibrillation may require blood thinners, such as aspirin or warfarin. In rare instances when mitral valve prolapse is associated with severe mitral regurgitation, surgical repair or replacement of the mitral valve may be necessary. Mitral valve repair is generally considered preferable to replacement. Current ACC/AHA guidelines promote repair of mitral valve in people before symptoms of heart failure develop. Symptomatic people, those with evidence of diminished left ventricular function, or those with left ventricular dilatation need urgent attention.

Prevention of infective endocarditis

Individuals with MVP are at higher risk of bacterial infection of the heart, called infective endocarditis. This risk is approximately three- to eightfold the risk of infective endocarditis in the general population.[2] Until 2007, the American Heart Association recommended prescribing antibiotics before invasive procedures, including those in dental surgery. Thereafter, they concluded that "prophylaxis for dental procedures should be recommended only for patients with underlying cardiac conditions associated with the highest risk of adverse outcome from infective endocarditis."[17]

Many organisms responsible for endocarditis are slow-growing and may not be easily identified on routine blood cultures (these fastidious organisms require special culture media to grow). These include the HACEK organisms, which are part of the normal oropharyngeal flora and are responsible for perhaps 5 to 10% of infective endocarditis affecting native valves. It is important when considering endocarditis to keep these organisms in mind.

Prognosis

Generally, MVP is benign. However, MVP patients with a murmur, not just an isolated click, have an increased mortality rate of 15-20%.[18] The major predictors of mortality are the severity of mitral regurgitation and the ejection fraction.[19]

Epidemiology

Prior to the strict criteria for the diagnosis of mitral valve prolapse, as described above, the incidence of mitral valve prolapse in the general population varied greatly.[10] Some studies estimated the incidence of mitral valve prolapse at 5 to 15 percent or even higher.[20] One 1985 study suggested MVP in up to 35% of healthy teenagers.[21]

Recent elucidation of mitral valve anatomy and the development of three-dimensional echocardiography have resulted in improved diagnostic criteria, and the true prevalence of MVP based on these criteria is estimated at 2-3%.[2] As a part of the Framingham Heart Study, for example, the prevalence of mitral valve prolapse in Framingham, MA was estimated at 2.4%. There was a near-even split between classic and nonclassic MVP, with no significant age or sex discrimination.[11] MVP is observed in 7% of autopsies in the United States.[18]

History

The term mitral valve prolapse was coined by J. Michael Criley in 1966 and gained acceptance over the other descriptor of "billowing" of the mitral valve, as described by John Brereton Barlow.[22]

References

- Barlow JB, Bosman CK (February 1966). "Aneurysmal protrusion of the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve. An auscultatory-electrocardiographic syndrome". Am. Heart J. 71 (2): 166–78. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(66)90179-7. PMID 4159172.

- Hayek E, Gring CN, Griffin BP (2005). "Mitral valve prolapse". Lancet. 365 (9458): 507–18. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17869-6. PMID 15705461.

- Criley JM, Lewis KB, Humphries JO, Ross RS (July 1966). "Prolapse of the mitral valve: clinical and cine-angiocardiographic findings". Br Heart J. 28 (4): 488–96. doi:10.1136/hrt.28.4.488. PMC 459076. PMID 5942469.

- Ahmed, Mustafa I.; Sanagala, Thriveni; Denney, Thomas; Inusah, Seidu; McGiffin, David; Knowlan, Donald; O’Rourke, Robert A.; Dell’Italia, Louis J. (August 2009). "Mitral Valve Prolapse With a Late-Systolic Regurgitant Murmur May Be Associated With Significant Hemodynamic Consequences". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 338 (2): 113–115. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31819d5ec6. PMID 19561453.

- Tanser, Paul H. (reviewed Mar 2007). "Mitral Valve Prolapse", The Merck Manuals Online Medical Library, Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- Kolibash AJ (1988). "Progression of mitral regurgitation in patients with mitral valve prolapse". Herz. 13 (5): 309–17. PMID 3053383.

- "Related Disorders: Mitral Valve Prolapse". Archived from the original on 2007-02-25. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- Lumiaho, A; Ikäheimo, R; Miettinen, R; Niemitukia, L; Laitinen, T; Rantala, A; Lampainen, E; Laakso, M; Hartikainen, J (2001). "Mitral valve prolapse and mitral regurgitation are common in patients with polycystic kidney disease type 1". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 38 (6): 1208–16. doi:10.1053/ajkd.2001.29216. PMID 11728952.

- "Pectus Excavatum: Epidemiology". Medscape. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- Playford, David; Weyman, Arthur (2001). "Mitral valve prolapse: time for a fresh look". Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2 (2): 73–81. PMID 12439384. Archived from the original on 2014-09-03. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- Freed LA, Levy D, Levine RA, Larson MG, Evans JC, Fuller DL, Lehman B, Benjamin EJ (1999). "Prevalence and clinical outcome of mitral-valve prolapse". N Engl J Med. 341 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM199907013410101. PMID 10387935.

- Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8. Archived from the original on 10 September 2005.

- NLM/NIH: Medline Plus Medical Encyclopedia: Rheumatic fever

- S Venkatesan; et al. (Sep–Oct 2007). "Can we diagnose Infective endocarditis without vegetation?". Indian Heart Journal. 59 (5).

- Toomer KA, Yu M, Fulmer D, Guo L, Moore KS, Moore R, Drayton KD, Glover J, Peterson N, Ramos-Ortiz S, Drohan A, Catching BJ, Stairley R, Wessels A, Lipschutz JH, Delling FN, Jeunemaitre X, Dina C, Collins RL1, Brand H10, Talkowski ME10, Del Monte F11, Mukherjee R, Awgulewitsch A, Body S, Hardiman G, Hazard ES, da Silveira WA, Wang B, Leyne M, Durst R, Markwald RR, Le Scouarnec S, Hagege A, Le Tourneau T, Kohl P, Rog-Zielinska EA, Ellinor PT, Levine RA, Milan DJ, Schott JJ, Bouatia-Naji N, Slaugenhaupt SA, Norris RA (2019) Primary cilia defects causing mitral valve prolapse. Sci Transl Med 11(493)

- "Mitral valve prolapse". Mayo Clinic.

- Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. (2007). "Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association" (PDF). Journal of the American Dental Association. 138 (6): 739–45, 747–60. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0262. PMID 17545263.

- Mitral Valve Prolapse at eMedicine

- Rodgers, Ellie (May 11, 2004). "Mitral Valve Regurgitation". Healthwise, on Yahoo. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- Levy D, Savage D (1987). "Prevalence and clinical features of mitral valve prolapse". Am Heart J. 113 (5): 1281–90. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(87)90956-2. PMID 3554946.

- Warth DC, King ME, Cohen JM, Tesoriero VL, Marcus E, Weyman AE (May 1985). "Prevalence of mitral valve prolapse in normal children". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 5 (5): 1173–7. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(85)80021-8. PMID 3989128.

- Barlow JB, Bosman CK (1966). "Aneurysmal protrusion of the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve. An auscultatory-electrocardiographic syndrome". Am Heart J. 71 (2): 166–78. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(66)90179-7. PMID 4159172.

Further reading

- Confronting Mitral Valve Prolapse Syndrome by Lyn Frederickson, 1992, ISBN 0-44639-407-6

- Taking Control: Living With the Mitral Valve Prolapse Syndrome by Kristine A. Scordo, 2006, ISBN 1-42431-576-X

- Mitral Valve Prolapse: A Comprehensive Patient's Guide to a Happier and Healthier Life by Ariel Soffer, M.D., 2007, ISBN 0-61515-205-8

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |