Palaeolama

Palaeolama (lit. 'early llama') is an extinct genus of laminoid camelid that existed from the Late Pliocene to the Early Holocene (1.8 to 0.011 Ma).[2][3][4] Its range extended from North America to the intertropical region of South America.

| Palaeolama | |

|---|---|

| |

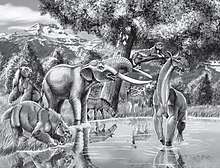

| Restoration of Palaeolama (below the gomphothere's tusks) and other mammals of Late Pleistocene Chile | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Camelidae |

| Tribe: | Lamini |

| Genus: | †Palaeolama Gervais, 1869 |

| Type species | |

| †Palaeolama weddeli Gervais, 1855 | |

| Species | |

|

†P. aequatorialis (Hoffstetter, 1952) | |

Description

Palaeolama were relatives of modern camelids that lived in the New World from the Late Pliocene to the Late Pleistocene or Early Holocene.[2][3][4] Fossil evidence suggests that it had a slender head, elongate snout, and stocky legs.[5][6] They likely weighed around 300 kilograms (660 lb), surpassing the weight of modern llamas.[6] They were specialized forest browsers and are often found in association with early equids, tapirs, deer, and mammoth.[2][4][7][8]

Morphology

Cranial

Palaeolama had a long, slender skull with an elongated rostrum and robust jaw. This morphology more closely resembles the cranial morphology of Hemiauchenia than that of modern llamas.[5]

Dental

The jaw and dental morphology of Palaeolama distinguish it from other laminae. Palaeolama tend to have a comparatively more dorsoventrally gracile mandible.[5][9] Like Hemiauchenia, Palaeolama lack their second deciduous premolars and can further be differentiated by the distinct size and shape of their third deciduous premolars. Their dentition has also been described as more brachyodont-like (short crowns, well developed roots).[9]

Post-cranial

Analyses of their limb elements reveal that they had shorter, stockier metapodials, and longer epipodials giving them a short, stocky appearance.[5] Limbs such as these are typically associated with organisms adapted to walking on uneven and rugged terrains. This is also suggestive of being well adapted to avoiding predators in forested areas.[4][5]

Diet

Various dietary analyses have concluded that Palaeolama was a specialized forest browser that relied almost exclusively on plants high in C3 for subsistence.[10][7][5][11] Additionally, its shallow jaw and brachydont "cheek teeth" are highly suggestive of a mixed or intermediate seasonal diet consisting of primarily leaves and fruits, with some grass.[5][10][11] Micro-wear analyses further validate this dietary interpretation.[5]

Group composition

It is inferred, from observations of modern llama, that Palaeolama probably organized into bands (consisting of a single male and multiple females) and troops (consisting exclusively of young males sometimes described as "bachelors"). Typically, band territories are defended by resident males while troops remain more or less free roaming until they form bands of their own.[5]

Habitat

Fossil evidence suggests Palaeolama was primarily adapted to low-temperate, arid climates and preferred open, forested, and high altitude mountainous regions.[4][8][5] The distribution of fossil evidence suggests that they had an altitudinal range limited exclusively by their dietary (vegetation) requirements.[5] Population density is shown to be highly dependent upon access and availability of subsistence resources.[5]

Range

The origins of this genus are a topic of much debate as some of the earliest fossils occur during both the Irvingtonian in Florida and the Ensenadan in Uruguay.[9] Despite this, agreement exists amongst paleobiologists on the dispersal of Palaeolama during the Great American Biotic Interchange.[2][4][9] There is also evidence suggesting a move to northern South America during the second of two Pleistocene Camilidae migration events.[4] Fossil evidence ranges from the southern extent of North America (including California, Florida, and Mexico) south through Central America and terminates in South America (Argentina and Uruguay).[2][4][8]

Palaeolama mirifica, the "stout-legged llama", is known from southern California and the southeastern U.S., with the highest concentration of fossil specimens found in Florida (specifically the counties of Alachua, Citrus, Hillsborough, Manatee, Polk, Brevard, Orange, Sumter and Levy). Other fossil occurrences have been discovered in Mexico, Central America (El Salvador) and South America (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Venezuela and Uruguay).[12]

Palaeolama major, identified by Liais in 1872, lived during the Late Pleistocene and was identified in fossil assemblages from northeastern and northern Brazil, the Pampean region of Argentina and Uruguay, northern Venezuela, and the coastal regions of Ecuador and northern Peru.[4]

Palaeolama wedelli, identified by Gervais in 1855, lived during the Mid-Late Pleistocene with fossil specimens found in southern Bolivia and the Andean region of Ecuador.[4]

Extinction

Climate change, changes and reductions in the types of vegetation they relied on, and human predation are all hypothesized to have contributed to the extinction of Palaeolama during the Late Pleistocene or Early Holocene.[5][9] Evidence from both the paleoecological and fossil-record suggest that Palaeolama, among other extinct camelids, weathered a number of glacial and interglacial episodes throughout their existence in North and South America. Their disappearance in some regions has been shown to coincide with a change in climate (to warmer, humid conditions) occurring at the end of the Pleistocene (also known as the Late Quaternary Warming) suggesting an inability to persevere.[5][13] This hypothesis is further supported by paleoecological evidence suggesting post-megafaunal extinction shifts in vegetation and whole ecosystems.[13]

However, the extinction timing of Palaeolama closely corresponds to the appearance of human big game hunting. Mathematical modeling has suggested that the 300 kg body mass of Palaeolama would have made it much more vulnerable to population depletion by both hunting and environmental change compared to the extant ~100 kg guanaco.[14]

See also

References

- "Fossilworks: Palaeolama". Fossilworks. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- Wheeler, J.C.; Chikhi, L.; Bruford, M.W. (2006). "Genetic Analysis of the Origins of Domestic South American Camelids". In Zeder, M.A.; Bradley, D.G.; Emshwiller, E.; Smith, B.D. (eds.). Documenting Domestication: New Genetic and Archaeological Paradigms. University of California Press. pp. 329–341. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.603.88. ISBN 9780520246386. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1pnvs1.28.

- "Fossilworks: Palaeolama". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- Scherer, C.S. (2013). "The Camelidae (Mammalia, Artiodactyla) from the Quaternary of South America: Cladistic and Biogeographic Hypotheses". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 20 (1): 45–56. doi:10.1007/s10914-012-9203-4. S2CID 207195863.

- Dompierre, H. (1995). Observations on the diets of six late Cenozoic North American camelids: Camelops, Hemiauchenia, Palaeolama, Procamelus, Alforjas, and Megatylopus. National Library of Canada. ISBN 0-612-02748-1. OCLC 46500746.

- Fariña, R.A.; Vizcaíno, S.F.; De Iuliis, G. (2013). Megafauna: Giant Beasts of Pleistocene South America. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-00230-3. JSTOR j.ctt16gzd2q. OCLC 779244424.

- Guérin, C.; Faure, M. (1999). "Palaeolama (Hemiauchenia) niedae sp. nov. from Northeastern Brazil and its' place among the South American Lamini". Geobios (in French). 32 (4): 629–659. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(99)80012-6.

- Salas, R.; Stucchi, M.; Devries, T.J. (2003). "The presence of Plio-Pleistocene Palaeolama sp. (Artiodactyla: Camelidae) on the southern coast of Peru". Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines. 32 (2): 347–359. doi:10.4000/bifea.6414.

- Ruez, D.R. (2005-09-30). "Earliest record of Palaeolama (Mammalia, Camelidae) with comments on "Palaeolama" guanajuatensis". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (3): 741–744. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0741:eropmc]2.0.co;2.

- Marcolino, C.P.; Isaias, R.M. dos S.; Cozzuol, M.A.; Cartelle, C.; Dantas, M.A.T. (2012). "Diet of Palaeolama major (Camelidae) of Bahia, Brazil, inferred from coprolites". Quaternary International. 278: 81–86. Bibcode:2012QuInt.278...81M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2012.04.002.

- MacFadden, B.J. (2000). "Cenozoic Mammalian Herbivores From the Americas: Reconstructing Ancient Diets and Terrestrial Communities". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 31 (1): 33–59. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.33.

- "Fossilworks: Palaeolama mirifica". fossilworks.org.

- Barnosky, .D.; Lindsey, E.L.; Villavicencio, N.A.; Bostelmann, E.; Hadly, E.A.; Wanket, J.; Marshall, C.R. (2015-10-26). "Variable impact of late-Quaternary megafaunal extinction in causing ecological state shifts in North and South America". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (4): 856–861. doi:10.1073/pnas.1505295112. PMC 4739530. PMID 26504219.

- Abramson, G.; Laguna, M.F.; Kuperman, M.N.; Monjeau, A.; Lanata, J.L. (2017). "On the roles of hunting and habitat size on the extinction of megafauna". Quaternary International. 431: 205–215. arXiv:1504.03202. Bibcode:2017QuInt.431..205A. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.043.