Pala d'Oro

Pala d’Oro (Italian, "Golden Pall" or "Golden Cloth") is the high altar retable of the Basilica di San Marco in Venice. It is universally recognized as one of the most refined and accomplished works of Byzantine enamel, with both front and rear sides decorated.

History

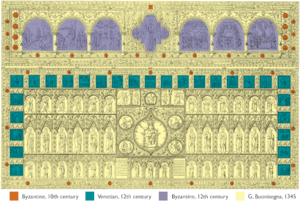

The Pala d’Oro was thought to be first commissioned in 976 by Doge Pietro Orseolo, where it was made up of precious stones and several enamels depicting various saints, and in 1105 it was expanded on by Doge Ordelaffo Falier.[1] In 1345, goldsmith Giovanni Paolo Bonesegna was commissioned to complete the altarpiece by Andrea Dandolo, who was the procurator at the time, and later became doge. Bonesegna added a Gothic-style frame to the piece, along with more precious stones.[2] Dandolo also included an inscription describing what his own additions were, along with those of his predecessors.[3]

Paolo Veneziano was commissioned to make wood panels to provide a cover (Pala Feriale) for when the altarpiece was not on display.[4] Veneziano was commissioned between 1342-4 to make this cover, where it was dated 1345 and signed by him along with his sons, Luca and Giovanni.[5] The cover is made from two pieces. The top plank features the Man of Sorrows in the center, who is surrounded by the Virgin and Sts. John, George, Mark, Peter, and Nicholas.[5] The bottom plank shows narratives of Life, Martyrdom, Burial, and Translation of St Mark.[5] The wooden panels were opened to the public during liturgies only. In the 15th century, Veneziano's "exterior" altarpiece was replaced by a wooden panel which remains today, though the Pala is now always open.

In 1995, Veneziano's wooden Pala Feriale cover underwent conservation treatment funded by the non-profit organization Save Venice Inc.

Description

The altarpiece is 3 meters (9.8 ft) wide by 2 meters (6.6 ft) tall.[6] It is made of gold and silver,[7] 187 enamel plaques,[5] and 1,927 gems.[2] These include 526 pearls, 330 garnets, 320 emeralds, 255 sapphires, 183 amethysts, 175 agates, 75 rubies, 34 topazes, 16 carnelians, and 13 jaspers.[2]

Top Section

The altarpiece consists of two parts. The enamels in the top section of the Pala d’Oro contain the Archangel Michael at the center, with six images depicting the Life of Christ on either side of him, which were added in 1209. They show the Entry of Christ into Jerusalem, Descent into Limbo, Crucifixion, Ascension, Pentecost, and Death of the Virgin.[2] It’s generally thought that these weren’t originally part of the altarpiece, as their stylistic features place them into the 12th century, and they were probably looted during the Fourth Crusade.[8]

Bottom Section

The bottom section contains the enamels that told the Life of St. Mark. These were created in 1105 in Constantinople, and were commissioned by Doge Ordelaffo Falier.[9] They used to be positioned along the base, but have since been moved to their current position along the sides and the top row of this section.[9]

Also in the bottom section is an enamel depicting Christ at the center of the altarpiece, and the four circular enamels around him are images of the Four Evangelists.[9] To the right and left of Christ are the twelve apostles, six to each side. Above Christ is an empty throne, which represents the Last Judgement and the Second Coming of Christ, with angels and archangels on either side of it.[3] Underneath Christ and the apostles are the twelve prophets, with the Virgin—flanked by Falier and Empress Irene—at the center.[9]

Doge Falier and Empress Irene

The two figures surrounding the Virgin are images of Doge Ordelaffo Falier and Byzantine Empress Irene.[10] The depiction of Falier seems to be slightly off as his head is too small in proportion to his body. There is evidence that shows the original head was removed, and replaced with a new one.[10] There are also scratches on the enamel from when the previous head was removed, and some type of wax or paste was used to fill in the gaps where the replacement piece didn’t exactly fit.[11]

While there have been theories that the previous head depicted an emperor, that explanation doesn’t quite fit. Emperors are usually depicted with red footwear, and this figure is wearing black footwear, with no signs of being altered.[11] Additionally, the enamel bears Falier’s name, which would have required a lot of effort to change, and would have left evidence behind.[11] The most likely explanation is that the original head was in fact Falier’s head, but without a halo.[11] Later, church officials—possibly even Falier himself—decided to replace it to include a halo. The scepter he’s holding restricted how much could be altered, which required the crafters to make the new image slightly smaller.[11]

Notes

- Paoletti and Radke 1997, p. 134.

- Vio, 2000, p. 167.

- Vio 2003, p. 300

- Paoletti and Radke 1997, p. 135.

- Gibbs 2014

- Vio, 2000, p. 163.

- Nagel, 2000.

- Gonosová 1978, p. 332.

- Vio, 2000, p. 166.

- Buckton and Osborne 2000, p. 43.

- Buckton and Osborne 2000, p. 44.

References

- Bettini, Sergio, "Venice, the Pala d'Oro, and Constantinople", in Buckton, David, et al., The Treasury of San Marco Venice, 1984, Metropolitan Museum of Art, (fully available online or as PDF from the MMA).

- Buckton, David, and John Osborne. "The Enamel of Doge Ordelaffo Falier on the Pala d'Oro in Venice." Gesta 39 no. 1 (2000): 43-49.

- Gibbs, Robert (2014). "Paolo Veneziano." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press.

- Gonosová, Anna. "A Study of an Enamel Fragment in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection." Dumbarton Oaks Papers 32 (1978): 327-333.

- Nagel, Alexander. "Altarpiece." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Paoletti, John T., and Gary M. Radke (1997). Art in Renaissance Italy. New York: H.N. Abrams.

- Vio, Ettore (2000). St Mark's Basilica in Venice. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Vio, Ettore (2003). St. Mark's: the Art and Architecture of Church and State in Venice. New York: Riverside Book Co.

Films

- Romer, John (1997), Byzantium: The Lost Empire; ABTV/Ibis Films/The Learning Channel; 4 episodes; 209 minutes. (In Episode 3 ["Envy of the World"], presenter Romer examines the Pala d'Oro in detail.)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pala d'Oro. |