Bearded vulture

The bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus), also known as the lammergeier (or lammergeyer)[lower-alpha 1][3][4] or ossifrage, is a bird of prey and the only member of the genus Gypaetus. This bird is also identified as Huma bird or Homa bird in Iran and north west Asia. Traditionally considered an Old World vulture, it actually forms a minor lineage of Accipitridae together with the Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus), its closest living relative. It is not much more closely related to the Old World vultures proper than to, for example, hawks, and differs from the former by its feathered neck. Although dissimilar, the Egyptian and bearded vulture each have a lozenge-shaped tail—unusual among birds of prey.

| Bearded vulture | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Gypaetus Storr, 1784 |

| Species: | G. barbatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Gypaetus barbatus | |

| |

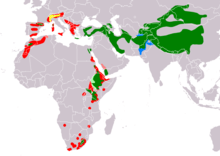

| Distribution of Gypaetus barbatus Resident Non-breeding Probably extinct Extinct Possibly Extant (resident) Extant & Reintroduced (resident) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The bearded vulture is the only known vertebrate whose diet consists almost exclusively (70 to 90 percent) of bone.[5] It lives and breeds on crags in high mountains in southern Europe, the Caucasus,[6][7][8] Africa,[9] the Indian subcontinent, and Tibet, laying one or two eggs in mid-winter that hatch at the beginning of spring. Populations are residents.

The population of this species continues to decline. Until July 2014, it was classified by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as being of least concern; it has, however, since been reassessed as near threatened.

Distribution and habitat

The lammergeier is sparsely distributed across a vast, considerable range. It can be found in mountainous regions from Europe east to Siberia (Palearctic) and Africa. It is found in the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Caucasus region, the Zagros Mountains, the Alborz, the Koh-i-Baba in Bamyan, Afghanistan, the Altai Mountains, the Himalayas, Ladakh in northern India, western and central China, Israel (Where although extinct as a breeder since 1981, single young birds have been reported in 2000, 2004 and 2016 [10]), and the Arabian Peninsula. In Africa, it is found in the Atlas Mountains, the Ethiopian Highlands and down from Sudan to northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, central Kenya and northern Tanzania. An isolated population inhabits the Drakensberg of South Africa.[11]

This species is almost entirely associated with mountains and inselbergs with plentiful cliffs, crags, precipices, canyons and gorges. They are often found near alpine pastures and meadows, montane grassland and heath, steep-sided, rocky wadis, high steppe and are occasional around forests. They seem to prefer desolate, lightly-populated areas where predators who provide many bones, such as wolves and golden eagles, have healthy populations.

In Ethiopia, they are now common at refuse tips on the outskirts of small villages and towns. Although they occasionally descend to 300–600 m (980–1,970 ft), bearded vultures are rare below an elevation of 1,000 m (3,300 ft) and normally reside above 2,000 m (6,600 ft) in some parts of their range. They are typically found around or above the tree line which are often near the tops of the mountains, at up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) in Europe, 4,500 m (14,800 ft) in Africa and 5,000 m (16,000 ft) in central Asia. In southern Armenia they have been found to breed below 1,000 m (3,300 ft) if cliff availability permits.[12] They even have been observed living at altitudes of 7,500 m (24,600 ft) on Mount Everest and been observed flying at a height of 24,000 ft (7,300 m).[6][7][8][11][13][14]

During 1970s and 1980s the population of the bearded vulture in southern Africa declined however their distribution remained constant. The bearded vulture population occupies the highlands of Lesotho, Free State, Eastern Cape and Maloti-Drakensberg mountains in KwaZulu-Natal. Adult bearded vultures utilise areas with higher altitudes, with steep slopes and sharp points and within areas that are situated closer to their nesting sites. Adult bearded vultures are more likely to fly below 200 m over Lesotho. Along the Drakensberg Escarpment from the area of Golden Gate Highlands National Park south into the northern part of the Eastern Cape there was the greatest densities of bearded vultures.

Abundance of bearded vultures is shown for eight regions within the species' range in southern Africa.[15] The total population of bearded vultures in southern Africa is calculated as being 408 adult birds and 224 young birds of all age classes therefore giving an estimate of about 632 birds.[15]

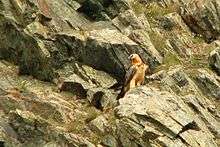

Description

This bird is 94–125 cm (37–49 in) long with a wingspan of 2.31–2.83 m (7.6–9.3 ft).[11] It weighs 4.5–7.8 kg (9.9–17.2 lb), with the nominate race averaging 6.21 kg (13.7 lb) and G. b. meridionalis of Africa averaging 5.7 kg (13 lb).[11] In Eurasia, vultures found around the Himalayas tend to be slightly larger than those from other mountain ranges.[11] Females are slightly larger than males.[11][16] It is essentially unmistakable with other vultures or indeed other birds in flight due to its long, narrow wings, with the wing chord measuring 71.5–91 cm (28.1–35.8 in), and long, wedge-shaped tail, which measures 42.7–52 cm (16.8–20.5 in) in length. The tail is longer than the width of the wing.[17] The tarsus is relatively small for the bird's size, at 8.8–10 cm (3.5–3.9 in). The proportions of the species have been compared to a falcon, scaled to an enormous size.[11]

Unlike most vultures, the bearded vulture does not have a bald head. This species is relatively small headed, although its neck is powerful and thick. It has a generally elongated, slender shape, sometimes appearing bulkier due to the often hunched back of these birds. The gait on the ground is waddling and the feet are large and powerful. The adult is mostly dark gray, rusty and whitish in color. It is grey-blue to grey-black above. The creamy-coloured forehead contrasts against a black band across the eyes and lores and bristles under the chin, which form a black beard that give the species its English name. Bearded vultures are variably orange or rust of plumage on their head, breast and leg feathers but this is actually cosmetic. This colouration may come from dust-bathing, rubbing mud on its body or from drinking in mineral-rich waters. The tail feathers and wings are gray. The juvenile bird is dark black-brown over most of the body, with a buff-brown breast and takes five years to reach full maturity. The bearded vulture is silent, apart from shrill whistles in their breeding displays and a falcon-like cheek-acheek call made around the nest.[11]

Nestlings are covered in dark down feathers

Nestlings are covered in dark down feathers The juvenile bird is mostly dark

The juvenile bird is mostly dark The adult has a buff-yellow body and head

The adult has a buff-yellow body and head Adult in flight from below (note the tail shape)

Adult in flight from below (note the tail shape) Adult spreading wings

Adult spreading wings

Physiology

The acid concentration of the bearded vulture stomach has been estimated to be of pH about 1. Large bones will be digested in about 24 hours, aided by slow mixing/churning of the stomach content. The high fat content of bone marrow makes the net energy value of bone almost as good as that of muscle, even if bone is less completely digested. A skeleton left on a mountain will dehydrate and become protected from bacterial degradation, and the bearded vulture can return to consume the remainder of a carcass even months after the soft parts have been consumed by other animals, larvae and bacteria.[18]

Behaviour

Diet and feeding

Like other vultures, it is a scavenger, feeding mostly on the remains of dead animals. The bearded vulture diet comprises mammals (93%), birds (6%) and reptiles (1%), with medium-sized ungulates forming a large part of the diet.[19] Bearded vultures avoid remains of larger species (such as cows and horses) probably because of the variable cost/benefit ratios in handling efficiency, ingestion process and transportation of the remains.[19] It usually disdains the actual meat and lives on a diet that is typically 85–90% bone marrow. This is the only living bird species that specializes in feeding on marrow.[11] The bearded vulture can swallow whole or bite through brittle bones up to the size of a lamb's femur[20] and its powerful digestive system quickly dissolves even large pieces. The bearded vulture has learned to crack bones too large to be swallowed by carrying them in flight to a height of 50–150 m (160–490 ft) above the ground and then dropping them onto rocks below, which smashes them into smaller pieces and exposes the nutritious marrow.[11] They can fly with bones up to 10 cm (3.9 in) in diameter and weighing over 4 kg (8.8 lb), or nearly equal to their own weight.[11]

After dropping the large bones, the bearded vulture spirals or glides down to inspect them and may repeat the act if the bone is not sufficiently cracked.[11] This learned skill requires extensive practice by immature birds and takes up to seven years to master.[21] Its old name of ossifrage ("bone breaker") relates to this habit. Less frequently, these birds have been observed trying to break bones (usually of a medium size) by hammering them with their bill directly into rocks while perched.[11] During the breeding season they feed mainly on carrion. They prefer limbs of sheep and other small mammals and they carry the food to the nest, unlike other vultures which feed their young by regurgitation.[19]

Live prey is sometimes attacked by the bearded vulture, with perhaps greater regularity than any other vulture.[11] Among these, tortoises seem to be especially favored depending on their local abundance. Tortoises preyed on may be nearly as heavy as the preying vulture. To kill tortoises, bearded vultures fly with them to some height and drop them to crack open the bulky reptiles' hard shells. Golden eagles have been observed to kill tortoises in the same way.[11] Other live animals, up to nearly their own size, have been observed to be predaciously seized and dropped in flight. Among these are rock hyraxes, hares, marmots and, in one case, a 62 cm (24 in) long monitor lizard.[11][20] Larger animals have been known to be attacked by bearded vultures, including ibex, Capra goats, chamois and steenbok.[11] These animals have been killed by being surprised by the large birds and battered with wings until they fall off precipitous rocky edges to their deaths; although in some cases these may be accidental killings when both the vulture and the mammal surprise each other.[11] Many large animals killed by bearded vultures are unsteady young, or have appeared sickly or obviously injured.[11] Humans have been anecdotally reported to have been killed in the same way. This is unconfirmed, however, and if it does happen, most biologists who have studied the birds generally agree it would be accidental on the part of the vulture.[11] Occasionally smaller ground-dwelling birds, such as partridges and pigeons, have been reported eaten, possibly either as fresh carrion (which is usually ignored by these birds) or killed with beating wings by the vulture.[11] While foraging for bones or live prey while in flight, bearded vultures fly fairly low over the rocky ground, staying around 2 to 4 m (6.6 to 13.1 ft) high.[11] Occasionally, breeding pairs may forage and hunt together.[11] In the Ethiopian Highlands, bearded vultures have adapted to living largely off human refuse.[11]

Breeding

The bearded vulture occupies an enormous territory year-round. It may forage over two square kilometers each day. The breeding period is variable, being December through September in Eurasia, November to June in the Indian subcontinent, October to May in Ethiopia, throughout the year in eastern Africa and May to January in southern Africa.[11] Although generally solitary, the bond between a breeding pair is often considerably close. Biparental monogamous care occurs in the bearded vulture.[22] In a few cases, polyandry has been recorded in the species.[11] The territorial and breeding display between bearded vultures is often spectacular, involving the showing of talons, tumbling and spiralling while in solo flight. The large birds also regularly lock feet with each other and fall some distance through the sky with each other.[11] In Europe the breeding pairs of bearded vultures are estimated to be 120.[23] The mean productivity of the bearded vulture is 0.43±0.28 fledgings/breeding pair/year and the breeding success averaged 0.56±0.30 fledgings/pair with clutches/year.[24]

The nest is a massive pile of sticks, that goes from around 1 m (3.3 ft) across and 69 cm (27 in) deep when first constructed up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft) across and 1 m (3.3 ft) deep, with a covering of various animal matter from food, after repeated uses. The female usually lays a clutch of 1 to 2 eggs, though 3 have been recorded on rare occasions.[11] which are incubated for 53 to 60 days. After hatching, the young spend 100 to 130 days in the nest before fledging. The young may be dependent on the parents for up to 2 years, forcing the parents to nest in alternate years on a regular basis.[11] Typically, the bearded vulture nests in caves and on ledges and rock outcrops or caves on steep rock walls, so are very difficult for nest-predating mammals to access.[20] Wild bearded vultures have a mean lifespan of 21.4 years,[25] but have been observed to live for up to at least 45 years in captivity.[26]

Reintroduction in the Alps

The bearded vulture had a very poor reputation in early modern Europe, due in large part to tales of the birds stealing babies and livestock. The growing availability of firearms, combined with bounties offered for dead vultures, caused a sharp decline in the bearded vulture population around the Alps. By the beginning of the 20th century, they had completely disappeared from the Alpine regions.

Efforts to reintroduce the bearded vulture began in earnest in the 1970s, in the French Alps. Zoologists Paul Geroudet and Gilbert Amigues attempted to release vultures that had been captured in Afghanistan, but this approach proved unsuccessful: it was too difficult to capture the vultures in the first place, and too many died in transport on their way to France. A second attempt was made in 1987, using a technique called "hacking," by which young individuals (from 90–100 days) from zoological parks would be taken from the nest and placed in a protected area in the Alps. As they were still unable to fly at that age, the chicks were hand-fed by humans until the birds learned to fly and were able to reach food without human assistance. This method has proven more successful, with over 200 birds released in the Alps from 1987 to 2015, and a bearded vulture population has reestablished itself in the Alps.[27]

Threats and conservation status

The bearded vulture is one of the most endangered European bird species as over the last century its abundance and breeding range have drastically declined.[28] It naturally occurs at low densities, with anywhere from a dozen to 500 pairs now being found in each mountain range in Eurasia where the species breeds. The species is most common in Ethiopia, where an estimated 1,400 to 2,200 are believed to breed.[11] Relatively large, healthy numbers seem to occur in some parts of the Himalayas as well. It was largely wiped out in Europe, and by the beginning of the 20th century the only substantial population was in the Spanish and French Pyrenees. Since then, it has been successfully reintroduced to the Swiss and Italian Alps, from where they have spread over into France.[11] They have also declined somewhat in parts of Asia and Africa, though less severely than in Europe.[11]

Many raptor species were shielded from anthropogenic influences in previously underdeveloped areas therefore they are greatly impacted as the human population rises and infrastructure increases in underdeveloped areas. The increase in human population and infrastructure results in the declines of the bearded vulture populations today. The increase of infrastructure includes the building of houses, roads and power lines and a major issue with infrastructure and bird species populations is the collision with power lines.[29] The declines of the bearded vulture populations have been documented throughout their range resulting from a decrease in habitat space, fatal collisions with energy infrastructure, reduced food availability, poisons left out for carnivores and direct persecution in the form of Trophy Hunting.[30]

This species is currently listed as near threatened by the IUCN Red List last accessed on 1 October 2016, the population continues to decline as the distribution ranges of this species continues to decline due to human development.

Conservation action

There have been mitigation plans that have been established to reduce the population declines in bearded vulture populations. One of these plans includes the South African Biodiversity Management Plan that has been ratified by the government to stop the population decline in the short term. Actions that have been implemented include the mitigation of existing and proposed energy structures to prevent collision risks, the improved management of supplementary feeding sites as well to reduce the populations from being exposed to human persecution and poisoning accidents and to also have outreach programmes that are aimed as reducing poisoning incidents.[29]

Etymology

This species was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae as Vultur barbatus.[31] The present scientific name means "bearded vulture-eagle".

The name lammergeyer originates from German Lämmergeier, which means "lamb-vulture". The name stems from the belief that it attacked lambs.[32]

In culture

The bearded vulture is considered a threatened species in Iran. Iranian mythology considers the rare bearded vulture (Persian: هما, 'Homa') the symbol of luck and happiness. It was believed that if the shadow of a Homa fell on one, he would rise to sovereignty[33] and anyone shooting the bird would die in forty days. The habit of eating bones and apparently not killing living animals was noted by Sa'di in Gulistan, written in 1258, and Emperor Jahangir had a bird's crop examined in 1625 to find that it was filled with bones.[34]

The ancient Greeks used ornithomancers to guide their political decisions: bearded vultures, or ossifragae were one of the few species of birds that could yield valid signs to these soothsayers.

The Greek playwright Aeschylus was said to have been killed in 456 or 455 BC by a tortoise dropped by an eagle who mistook his bald head for a stone – if this incident did occur, the bearded vulture is a likely candidate for the "eagle".

In the Bible/Torah, the bearded vulture, as the ossifrage, is among the birds forbidden to be eaten (Leviticus 11:13).

More recently, in 1944, Shimon Peres (called Shimon Persky at the time) and David Ben-Gurion found a nest of bearded vultures in the Negev desert. The bird is called peres in Hebrew, and Shimon Persky liked it so much he adopted it as his surname.[35] [36]

Robot bearded vultures appear in some science fiction literature, including the first volume of the Viriconium series by M. John Harrison and Feersum Endjinn by Iain M. Banks.

Notes

- The German spelling Lämmergeier is never used in English.

References

- "Fossilworks Gypaetus barbatus".

- BirdLife International (2013). "Gypaetus barbatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- American Heritage Dictionary

- Oxford Dictionaries Online

- "Bearded vulture".

- Gavashelishvili, A.; McGrady, M. J. (2006). "Breeding site selection by bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) and Eurasian griffon (Gyps fulvus) in the Caucasus". Animal Conservation. 9 (2): 159–170. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2005.00017.x.

- Gavashelishvili, A.; McGrady, M. J. (2006). "Geographic information system-based modelling of vulture response to carcass appearance in the Caucasus". Journal of Zoology. 269 (3): 365–372. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00062.x.

- Gavashelishvili, A.; McGrady, M. J. (2007). "Radio-satellite telemetry of a territorial Bearded Vulture Gypaetus barbatus in the Caucasus". Vulture News. 56: 4–13.

- Krüger, Sonja (2010-04-19). "Conservation of the Bearded Vulture Gypaetus barbatus meridionalis". Africanraptors.org. Retrieved 2012-08-08.

- "News from the field - Daily Updates". פורטל צפרות.

- Ferguson-Lees, James; Christie, David A. (2001). Raptors of the World. Illustrated by Kim Franklin, David Mead, and Philip Burton. Houghton Mifflin. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-618-12762-7. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- "Bearded Vulture". Armenian Bird Census Council. 2017.

- Bruce, Charles Granville (1923). The assault on Mount Everest 1922. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Subedi, Tulsi Ram; Anadón, José D.; Baral, Hem Sagar; Virani, Munir Z.; Sah, Shahrul Anuar Mohd (2020). "Breeding habitat and nest-site selection of Bearded Vulture Gypaetus barbatus in the Annapurna Himalaya Range of Nepal". Ibis. 162 (1): 153–161. doi:10.1111/ibi.12698. ISSN 1474-919X.

- Brown, C. J. (11 October 2010). "Distribution and status of the Bearded Vulture Gypaetus barbatus in southern Africa". Ostrich. 63 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1080/00306525.1992.9634172.

- Beaman, Mark; Madge, Steve (1999). The Handbook of Bird Identification for Europe and the Western Palearctic. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02726-5.

- Lee, W-S; Koo,T-H; Park, J-Y (2005). A Field Guide to the Birds of Korea. p. 98. ISBN 978-8995141533.

- Houston, D.C.; Copsey, J.A. (1994). "Bone Digestion and Intestinal Morphology of the Bearded Vulture" (PDF). J. Raptor Res. 28 (2): 73–78. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- Margalida, Antoni; Bertra, Joan; Heredia, Rafael (23 March 2009). "Diet and food preferences of the endangered Bearded Vulture Gypaetus barbatus: a basis for their conservation". Ibis. 151 (2): 235–243. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919x.2008.00904.x.

- "Lammergeier Vulture". The Living Edens — Bhutan. PBS. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- "Lammergeier (video, facts and news)". Wildlife Finder. BBC. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- Margalida, Antoni; Bertran, Joan (28 June 2008). "Breeding behaviour of the Bearded Vulture Gypaetus barbatus: minimal sexual differences in parental activities". Ibis. 142 (2): 225–234. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2000.tb04862.x.

- Donazar, J. A.; Hiraldo, F.; Bustamante, J. (1993). "Factors Influencing Nest Site Selection, Breeding Density and Breeding Success in the Bearded Vulture (Gypaetus barbatus)". Journal of Applied Ecology. 30 (3): 504–514. doi:10.2307/2404190. hdl:10261/47110. JSTOR 2404190.

- Margalida, Antoni; Garcia, Diego; Bertran, Joan; Heredia, Rafael (27 March 2003). "Breeding biology and success of the Bearded Vulture Gypaetus barbatus in the eastern Pyrenees". Ibis. 145 (2): 244–252. doi:10.1046/j.1474-919X.2003.00148.x.

- Brown, C.J. (March 1997). "Population dynamics of the bearded vulture Gypaetus barbatus in southern Africa". African Journal of Ecology. 35 (1): 53–63. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1997.048-89048.x.

- Antor, Ramón J.; Margalida, Antoni; Frey, Hans; Heredia, Rafael; Lorente, Luis; Sesé, José Antonio (July 2007). "First Breeding Age in Captive and Wild Bearded Vultures". Acta Ornithologica. 42 (1): 114–118. doi:10.3161/068.042.0106.

- http://gypaetebarbu.ch/project/reintroduction, 31.5.2018, Pro Gypaète

- Bretagnolle, Vincent; Inchausti, Pablo; Seguin, Jean-François; Thibault, Jean-Claude (November 2004). "Evaluation of the extinction risk and of conservation alternatives for a very small insular population: the bearded vulture Gypaetus barbatus in Corsica". Biological Conservation. 120 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2004.01.023.

- Kruger, Sonja; Reid, Timothy; Amar, Arjun (2014). "Differential Range Use between Age Classes of Southern African Bearded Vultures Gypaetus barbatus". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e114920. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k4920K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0114920. PMC 4281122. PMID 25551614.

- "Lammergeier". howstuffworks.com. Discovery Communications. 2008-04-22. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

-

Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). v.1. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 87.

V. albidus, dorso fusco, jugulo barbato, rostro incarnato, capite linea nigra cincto.

- Everett, Mike (2008). "Lammergeiers and lambs". British Birds. 101 (4): 215.

- Pollard, J. R. T. (5 January 2009). "The Lammergeyer Comparative Descriptions in Aristotle and Pliny". Greece and Rome. 16 (46): 23–28. doi:10.1017/s0017383500009311.

- Phillott, D.C. (1906). "Note on the Huma or Lammergeyer". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 2 (10): 532–533.

- Marche, Stephen (2008-06-13). "Flight of Fancy". The New Republic. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- Leshem, Yossi. "In Memory of Israel's 9th President, Shimon Peres, 'The National Bird'". Retrieved 2018-06-05.

External links

- Video of lammergeier shattering bones into smaller pieces on which it then feeds at ARKive

- Species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- Facts and Characteristics: Bearded Vulture at Vulture Territory

- The Lammergeier in Spain

- Cine and photo work about the Bearded Vulture in the Alps

- diet information

- Bearded Vulture in Armenia, Armenian Bird Census Council. 2017.

- Bone-eating vulture and a snow wolf

- Robert, Isabelle; Vigne, Jean-Denis (July 2002). "The Bearded Vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) as an Accumulator of Archaeological Bones. Late Glacial Assemblages and Present-day Reference Data in Corsica (Western Mediterranean)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 29 (7): 763–777. doi:10.1006/jasc.2001.0778.