Orthographic projection in cartography

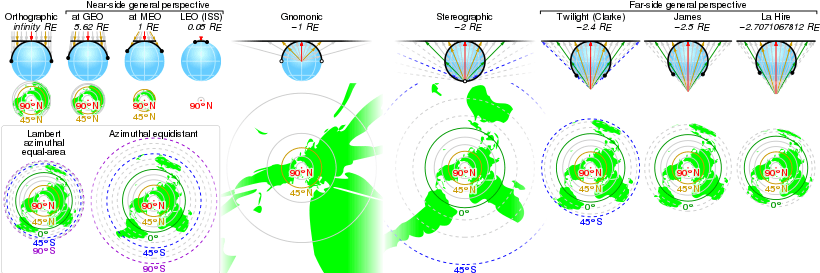

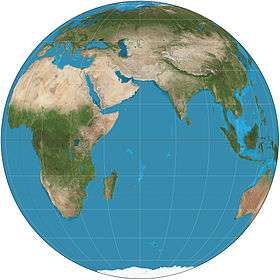

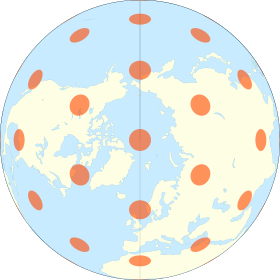

The use of orthographic projection in cartography dates back to antiquity. Like the stereographic projection and gnomonic projection, orthographic projection is a perspective (or azimuthal) projection, in which the sphere is projected onto a tangent plane or secant plane. The point of perspective for the orthographic projection is at infinite distance. It depicts a hemisphere of the globe as it appears from outer space, where the horizon is a great circle. The shapes and areas are distorted, particularly near the edges.[1][2]

History

The orthographic projection has been known since antiquity, with its cartographic uses being well documented. Hipparchus used the projection in the 2nd century B.C. to determine the places of star-rise and star-set. In about 14 B.C., Roman engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio used the projection to construct sundials and to compute sun positions.[2]

Vitruvius also seems to have devised the term orthographic (from the Greek orthos (= “straight”) and graphē (= “drawing”)) for the projection. However, the name analemma, which also meant a sundial showing latitude and longitude, was the common name until François d'Aguilon of Antwerp promoted its present name in 1613.[2]

The earliest surviving maps on the projection appear as woodcut drawings of terrestrial globes of 1509 (anonymous), 1533 and 1551 (Johannes Schöner), and 1524 and 1551 (Apian). These were crude. A highly refined map designed by Renaissance polymath Albrecht Dürer and executed by Johannes Stabius appeared in 1515.[2]

Photographs of the Earth and other planets from spacecraft have inspired renewed interest in the orthographic projection in astronomy and planetary science.

Mathematics

The formulas for the spherical orthographic projection are derived using trigonometry. They are written in terms of longitude (λ) and latitude (φ) on the sphere. Define the radius of the sphere R and the center point (and origin) of the projection (λ0, φ0). The equations for the orthographic projection onto the (x, y) tangent plane reduce to the following:[1]

Latitudes beyond the range of the map should be clipped by calculating the distance c from the center of the orthographic projection. This ensures that points on the opposite hemisphere are not plotted:

- .

The point should be clipped from the map if cos(c) is negative.

The inverse formulas are given by:

where

For computation of the inverse formulas the use of the two-argument atan2 form of the inverse tangent function (as opposed to atan) is recommended. This ensures that the sign of the orthographic projection as written is correct in all quadrants.

The inverse formulas are particularly useful when trying to project a variable defined on a (λ, φ) grid onto a rectilinear grid in (x, y). Direct application of the orthographic projection yields scattered points in (x, y), which creates problems for plotting and numerical integration. One solution is to start from the (x, y) projection plane and construct the image from the values defined in (λ, φ) by using the inverse formulas of the orthographic projection.

See References for an ellipsoidal version of the orthographic map projection.[3]

Orthographic projections onto cylinders

In a wide sense, all projections with the point of perspective at infinity (and therefore parallel projecting lines) are considered as orthographic, regardless of the surface onto which they are projected. These kinds of projections distort angles and areas close to the poles.

An example of an orthographic projection onto a cylinder is the Lambert cylindrical equal-area projection.

References

- Snyder, J. P. (1987). Map Projections—A Working Manual (US Geologic Survey Professional Paper 1395). Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. pp. 145–153.

- Snyder, John P. (1993). Flattening the Earth: Two Thousand Years of Map Projections pp. 16–18. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226767475.

- Zinn, Noel (June 2011). "Ellipsoidal Orthographic Projection via ECEF and Topocentric (ENU)" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-11-11.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Orthographic projection (cartography). |