Origins of opera

The art form known as opera originated in Italy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, though it drew upon older traditions of medieval and Renaissance courtly entertainment. The word opera, meaning "work" in Italian, was first used in the modern musical and theatrical sense in 1639 and soon spread to the other European languages. The earliest operas were modest productions compared to other Renaissance forms of sung drama, but they soon became more lavish and took on the spectacular stagings of the earlier genre known as intermedio.

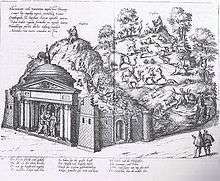

Dafne by Jacopo Peri was the earliest composition considered opera, as understood today,[1] although with only five instrumental parts it was much more like a chamber opera than either the preceding intermedi or the operas of Claudio Monteverdi a few years later. It was written around 1597, largely under the inspiration of an elite circle of literate Florentine humanists who gathered as the "Camerata". Significantly, Dafne was an attempt to revive the classical Greek drama, part of the wider revival of antiquity characteristic of the Renaissance. The members of the Camerata considered that the "chorus" parts of Greek dramas were originally sung, and possibly even the entire text of all roles; opera was thus conceived as a way of "restoring" this situation. The libretto was by Ottavio Rinuccini, who had written some of the 1587 Medici intermedi, in which Peri had also been involved; Rinuccini appears to have recycled some of the material, at least from the scene illustrated at right. Most of the music for "Dafne" is lost (the libretto was printed and survives), but one of Peri's many later operas, Euridice, dating from 1600, is the first opera score to have survived to the present day.

Traditions of staged sung music and drama go back to both secular and religious forms from the Middle Ages, and at the time opera first appears the Italian intermedio had courtly equivalents in various countries.

Etymology

The Italian word opera means "work", both in the sense of the labor done and the result produced. The Italian word in turn derives from the Latin opera. Opera is also the Latin plural of opus, with the same root, but the word opera was a singular Latin noun in its own right, and according to Lewis and Short, in Latin "opus is used mostly of the mechanical activity of work, as that of animals, slaves, and soldiers; opera supposes a free will and desire to serve". According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the Italian word was first used in the sense "composition in which poetry, dance, and music are combined" in 1639; the first recorded English usage in this sense dates to 1648.[2]

Italian origins of opera

Peri's works, however, did not arise out of a creative vacuum in the area of sung drama. An underlying prerequisite for the creation of opera proper was the practice of monody. Monody is the solo singing/setting of a dramatically conceived melody, designed to express the emotional content of the text it carries, which is accompanied by a relatively simple sequence of chords rather than other polyphonic parts. Italian composers began composing in this style late in the 16th century, and it grew in part from the long-standing practise of performing polyphonic madrigals with one singer accompanied by an instrumental rendition of the other parts, as well as the rising popularity of more popular, more homophonic vocal genres such as the frottola and the villanella. In these latter two genres, the increasing tendency was toward a more homophonic texture, with the top part featuring an elaborate, active melody, and the lower ones (usually these were three-part compositions, as opposed to the four-or-more-part madrigal) a less active supporting structure. From this, it was only a small step to fully-fledged monody. All such works tended to set humanist poetry of a type that attempted to imitate Petrarch and his Trecento followers, another element of the period's tendency toward a desire for restoration of principles it associated with a mixed-up notion of antiquity.

The solo madrigal, frottola, villanella and their kin featured prominently in the intermedio or intermezzo, theatrical spectacles with music that were funded in the last seventy years of the 16th century by the opulent and increasingly secular courts of Italy's city-states. Such spectacles, were usually staged to commemorate significant state events: weddings, military victories, and the like, and alternated in performance with the acts of plays. Like the later opera, an intermedi featured the aforementioned solo singing, but also madrigals performed in their typical multi-voice texture, and dancing accompanied by the present instrumentalists. They were lavishly staged, and led the scenography of the second half of the 16th century. The intermedi tended not to tell a story as such, although they occasionally did, but nearly always focused on some particular element of human emotion or experience, expressed through mythological allegory.

The staging in 1600 of Peri's opera Euridice as part of the celebrations for a Medici wedding, the occasions for the most spectacular and internationally famous intermedi of the previous century, was probably a crucial development for the new form, putting it in the mainstream of lavish courtly entertainment.

Another popular court entertainment at this time was the "madrigal comedy", later also called "madrigal opera" by musicologists familiar with the later genre. This consisted of a series of madrigals strung together to suggest a dramatic narrative, but not staged.[3] There were also two staged musical "pastoral"s, Il Satiro and La Disperazione di Fileno, both produced in 1590 and written by Emilio de' Cavalieri. Although these lost works seem only to have included arias, with no recitative, they were apparently what Peri was referring to, in his preface to the published edition of his Euridice, when he wrote: "Signor Emilio del Cavalieri, before any other of whom I know, enabled us to hear our kind of music upon the stage".[4] Other pastoral plays had long included some musical numbers; one of the earliest, La fabula d'Orfeo (1480) by Poliziano had at least three solo songs and one chorus.[5]

The French ballet de cour and the English masque

In addition to opera in Italy, developing concurrently in the late 16th-early 17th centuries were the particular national forms of the French ballet de cour, as part of Catherine de' Medici's court festivals, and the English masque, which were similar to the Italian intermedi in many respects, including an emphasis on spectacular staging. In both cases, the main difference apart from local musical style was a greater degree of audience participation in the form of staged or processional dances. At this time, of course, the audience consisted primarily of invited nobles and courtiers, although the 1589 Medici intermedi were repeated three times for a wider audience. The English masque also featured a culminating "revel," in which the performers drifted into and cavorted with the audience. Opera was imported into both countries by the middle of the 17th century, where it fused with the local incipient genres. This led to the dominance of ballet in opera of the French tradition.

The first German opera

Schütz's Dafne (1627) was the first lost German opera, though Staden's Seelewig (1644) is the first surviving German opera.

The first English opera

In England the masque tradition was too strongly associated with the court of Charles I to survive the outbreak of the English Civil War. Although, rather improbably, it was under the totalitarian and puritanical regime of Oliver Cromwell that the first Opera in English, The Siege of Rhodes, was produced in 1656, opera received no encouragement from that regime, and no subsidy from the post-Restoration government of Charles II, who preferred comedies and those who acted in them. This lack of financial backing, and the thriving English tradition of incidental music, made it difficult for Italian-style opera to take hold there. Instead the English semi-opera developed, although these were not produced in very large numbers. Even after imported Italian operas began to be staged, English composers were extremely slow to attempt the genre.

Other ancestors of opera

Religious

In earlier times, music had been part of medieval mystery plays, with the composer of these best known to modern audiences being Hildegard of Bingen. Whether these are to be regarded as possible progenitors of opera is highly debatable. Major liturgical celebrations were often dramatic to a considerable degree, featuring elaborate processions, tableaux vivants and liturgical drama; the Missa Aurea is the best-known example. A new, 17th century form of religious drama, the oratorio did arise shortly after the advent of opera, though it owes at least as much to the (originally secular) non-dramatic recitative-aria form of the cantata.

Secular

The origins of opera clearly lie in the court, whereas the mystery plays were normally a bourgeois form, entrusted to the guilds. But various forms of medieval court festivities combined music and drama; in the Gothic period major royal banquets, such as the Burgundian Feast of the Pheasant of 1454, were accompanied by performances, often elaborately staged re-enactments of military actions, with courtiers taking the parts. Unlike the liturgical dramas, which have survived in large numbers, at least as far as the scripts are concerned, we have only cursory descriptions of earlier court dramatic spectacles. A Royal entry was typically accompanied by various short performances, including tableaux vivants and mascarades.

Notes

- This is not agreed by all authorities, see Grout and Williams, 41 (footnote) for references to other views.

- Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed., s.v. "opera".

- Grout and Williams, 33

- JSTOR Peri and Corsi's "Dafne": Some New Discoveries and Observations, William V. Porter; Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Summer, 1965), p. 170

- Grout and Williams, 30

References

- Donald Jay Grout, Hermine Weigel Williams; A Short History of Opera, 2003 (first edn 1947),Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-11958-5; Excerpts online

- Roy Strong; Art and Power; Renaissance Festivals 1450–1650, 1984, The Boydell Press; ISBN 0-85115-200-7