Old Hijazi Arabic

Old Hejazi, or Old Higazi, is a variety of Old Arabic attested in Hejaz from about the 1st century to the 7th century. It is the variety thought to underlie the Quranic Consonantal Text (QCT) and in its later iteration was the prestige spoken and written register of Arabic in the Umayyad Caliphate.

| Old Hejazi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Region | Hejaz |

| Era | 1st century to 7th century |

Afroasiatic

| |

| Dadanitic, Arabic, Greek | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | None |

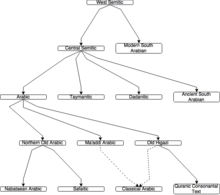

Classification

Old Ḥejāzī is characterized by the innovative relative pronoun ʾallaḏī (Arabic: ٱلَّذِي), ʾallatī (Arabic: ٱلَّتِي), etc., which is attested once in the inscription JSLih 384 and is the common form in the QCT,[1] as opposed to the form ḏ- which is otherwise common to Old Arabic.

The infinitive verbal complement is replaced with a subordinating clause ʾan yafʿala, attested in the QCT and a fragmentary Dadanitic inscription.

The QCT along with the papyri of the first century after the Islamic conquests attest a form with an l-element between the demonstrative base and the distal particle, producing from the original proximal set ḏālika and tilka.

The emphatic interdental and lateral were realized as voiced, in contrast to Northern Old Arabic, where they were voiceless.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Denti-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | plain | emphatic | |||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||

| Stop | voiceless | p ف | t | tˤ | k | kʼ ~ q ق | ʔ1 | |||

| voiced | b | d | ɟ ~ g ج | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | θ | s | sˤ | ʃ | x | ħ | h | ||

| voiced | ð | z | ðˤ | ɣ | ʕ | |||||

| Lateral | ɮˤ ~ d͡ɮˤ ض | |||||||||

| Flap / Trill | r | |||||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||||||

The sounds in the chart above are based on the constructed phonology of Proto-Semitic and the phonology of Modern Hejazi Arabic.

Notes:

- The consonants ⟨ض⟩ and ⟨ظ⟩ were voiced, in contrast with Northern Old Arabic, where they may have been voiceless[2]

- The glottal stop /ʔ/ was lost in Old Hejazi, except after word-final [aː].[3] It is still retained in Modern Hejazi in few positions.

- Historically, it is not well known in which stage of Arabic the shift from the Old Hejazi phonemes /p/, /g/, /q/ and /ɮˤ/ to Modern Hejazi /f/ ⟨ف⟩, /d͡ʒ/ ⟨ج⟩, /g/ ⟨ق⟩ and /dˤ/ ⟨ض⟩ occurred. Although the change in /g/ and /kʼ ~ q/ has been attested as early as the eighth century CE, and it can be explained by a chain shift / kʼ ~ q / → /g/ → /d͡ʒ/.[4] (See Hejazi Arabic)

Vowels

| Short | Long | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | Front | Back | |

| Close | i | u | iː | uː |

| Mid | (e) | eː | oː | |

| Open | a | aː | ||

In contrast to Classical Arabic, Old Hejazi had the phonemes [eː] and [oː], which arose from the contraction of Old Arabic [aja] and [awa], respectively. It also may have had short [e] from the reduction of [eː] in closed syllables:[5]

The QCT attests a phenomenon of pausal final long -ī dropping, which was virtually obligatory.[6]

| last shared ancestor | QCT (Old Hejazi) | Classical Arabic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *-awv- | dáʿawa | دعا | dáʿā | dáʿā |

| sánawun | سنا | sánā | sánan | |

| nájawatun | نجوه | najáwatu > najṓh | nájātun | |

| nájawatu-ka | نجاتك | najawátu-ka > najātu-k | nájātu-ka | |

| *-ajv- | hádaya | هدى | hádē | hádā |

| fátayun | فتى | fátē | fátan | |

| túqayatun | تقىه | tuqáyatu > tuqḗh | túqātun | |

| túqayati-hu | تقاته | tuqayáti-hu > tuqāt́i-h | tuqāt́i-hi | |

Example

Here is an example of reconstructed Old Hejazi side-by-side with its classicized form, with remarks on phonology:

| Old Hejazi (reconstructed) | Classicized (Hafs) |

|---|---|

| bism allāh alraḥmān alraḥīm

1) ṭāhā 2) mā anzalnā ʿalayk alqurān litašqē 3) illā taḏkirah liman yaḫšē 4) tanzīlā mimman ḫalaq alarḍ walsamāwāt alʿulē 5) alraḥmān ʿalay alʿarš astawē 6) lah mā fī lsamāwāt wamā fī larḍ wamā baynahumā wamā taḥt alṯarē 7) waïn taǧhar bilqawl faïnnah yaʿlam alsirr waäḫfē 8) allāh lā ilāh illā huww lah alasmāʾ alḥusnē 9) wahal atēk ḥadīṯ mūsē 10) iḏ rāʾ nārā faqāl liählih amkuṯū innī ānast nārā laʿallī ātīkum minhā biqabas aw aǧid ʿalay alnār hudē 11) falammā atēhā nūdī yāmūsē 12) innī anā rabbuk faäḫlaʿ naʿlayk innak bilwād almuqaddas ṭuwē |

bismi llāhi rraḥmāni rraḥīm

1) ṭāhā 2) mā ʾanzalnā ʿalayka lqurʾāna litašqā 3) ʾillā taḏkiratan liman yaḫšā 4) tanzīlan mimman ḫalaqa lʾarḍa wassamāwāti lʿulā 5) ʾarraḥmānu ʿalā lʿarši stawā 6) lahū mā fī ssamāwāti wamā fī lʾarḍi wamā baynahumā wamā taḥta ṯṯarā 7) waʾin taǧhar bilqawli faʾinnahū yaʿlamu ssirra waʾaḫfā 8) ʾallāhu lā ʾilāha ʾillā huwa lahū lʾasmāʾu lḥusnā 9) wahal ʾatāka ḥadīṯu mūsā 10) ʾiḏ raʾā nāran faqāla liʾahlihī mkuṯū ʾinnī ʾānastu nāran laʿallī ʾātīkum minhā biqabasin ʾaw ʾaǧidu ʿalā nnāri hudā 11) falammā ʾatāhā nūdiya yāmūsā 12) ʾinnī ʾana rabbuka faḫlaʿ naʿlayka ʾinnaka bilwādi lmuqaddasi ṭuwā |

Notes:

- Basmala: final short vowels are lost in context, the /l/ is not assimilated in the definite article

- Line 2: the glottal stop is lost in /qurʾān/ (> /qurān), proto-Arabic */tišqaya/ collapses to /tašqē/

- Line 3: /taḏkirah/ < */taḏkirat/ < */taḏkirata/. The feminine ending was probably diptotic in Old Hejazi, and without nunation[7]

- Line 4: /tanzīlā/ from loss of nunation and subsequent lengthening. Loss of glottal stop in /alarḍ/ has evidence in early scribal traditions[8] and is supported by Warsh

- Line 5: Elision of the definite article's vowel in /lʿarš/ is supported by similar contextual elision in the Damascus psalm fragment. /astawē/ with fixed prothetic /a-/ is considered a hallmark of Old Hejazi, and numerous examples are found in the Damascus psalm fragment and support for it is found as well in Judeo-Christian Arabic texts. The word /ʿalay/ contains an uncollapsed final diphthong.

- Line 8: Old Hejazi may have had /huww/ < */huwwa/ < */hūwa/ < */hūʾa/ with an originally long vowel instead of /huwa/ < */huʾa/ as in Classical Arabic. This is supported by its spelling هو which indicates a consonantal /w/ rather than هوا had the word ended in a /ū/.

- Line 10: The orthography indicates /rāʾ/ , from */rāʾa/ < */rāya/ < */raʾaya/[9]

Grammar

Proto-Arabic

| Triptote | Diptote | Dual | Masculine Plural | Feminine Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -un | -u | -āni | -ūna | -ātun |

| Accusative | -an | -a | -ayni | -īna | -ātin |

| Genitive | -in |

Proto-Arabic nouns could take one of the five above declensions in their basic, unbound form.

Notes

The definite article spread areally among the Central Semitic languages and it would seem that Proto-Arabic lacked any overt marking of definiteness.

Old Hejazi (Quranic Consonantal Text)

| Triptote | Diptote | Dual | Masculine Plural | Feminine Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -∅ | ʾal-...-∅ | -∅ | (ʾal-)...-ān | (ʾal-)...-ūn | (ʾal-)...-āt |

| Accusative | -ā | (ʾal-)...-ayn | (ʾal-)...-īn | |||

| Genitive | -∅ | |||||

The Qur'anic Consonantal Text presents a slightly different paradigm to the Safaitic, in which there is no case distinction with determined triptotes, but the indefinite accusative is marked with a final /ʾ/.

Notes

In JSLih 384, an early example of Old Hejazi, the Proto-Central Semitic /-t/ allomorph survives in bnt as opposed to /-ah/ < /-at/ in s1lmh.

Old Ḥejāzī is characterized by the innovative relative pronoun ʾallaḏī, ʾallatī, etc., which is attested once in JSLih 384 and is the common form in the QCT.[1]

The infinitive verbal complement is replaced with a subordinating clause ʾan yafʿala, attested in the QCT and a fragmentary Dadanitic inscription.

The QCT along with the papyri of the first century after the Islamic conquests attest a form with an l-element between the demonstrative base and the distal particle, producing from the original proximal set ḏālika and tilka.

Writing systems

Dadanitic

A single text, JSLih 384, composed in the Dadanitic script, from northwest Arabia, provides the only non-Nabataean example of Old Arabic from the Ḥijāz.

Transitional Nabataeo-Arabic

A growing corpus of texts carved in a script in between Classical Nabataean Aramaic and what is now called the Arabic script from Northwest Arabia provides further lexical and some morphological material for the later stages of Old Arabic in this region. The texts provide important insights as to the development of the Arabic script from its Nabataean forebear and are an important glimpse of the Old Ḥejāzī dialects.

Arabic (Quranic Consonantal Text and 1st c. Papyri)

The QCT represents an archaic form of Old Hejazi.

Greek (Damascus Psalm Fragment)

The Damascus Psalm Fragment in Greek script represents a later form of prestige spoken dialect in the Umayyad Empire that may have roots in Old Hejazi. It shares features with the QCT such as the non-assimilating /ʾal-/ article and the pronominal form /ḏālika/. However, it shows a phonological merger between [eː] and [aː] and the development of a new front allophone of [a(ː)] in non-emphatic contexts, perhaps realized [e(ː)].

See also

- Arabic language

- Varieties of Arabic

- Hejazi Arabic

- Semitic languages

References

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2015-03-27). An Outline of the Grammar of the Safaitic Inscriptions. Brill. p. 48. ISBN 9789004289826.

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2015). "On the Voiceless Reflex of *ṣ́ and *ṯ ̣ in pre-Hilalian Maghrebian Arabic". Journal of Arabic Linguistics (62): 88–95.

- Putten, Marijn van. "The *ʔ in the Quranic Consonantal Text - Presented at NACAL45 (9-11 June 2017, Leiden)". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Cantineau, Jean (1960). Cours de phonétique arabe (in French). Paris, France: Libraire C. Klincksieck. p. 67.

- Putten, Marijn van (2017). "The development of the triphthongs in Quranic and Classical Arabic". Arabian Epigraphic Notes. 3: 47–74.

- Stokes, Phillip; Putten, Marijn van. "M. Van Putten & P.W. Stokes - Case in the Quranic Consonantal Text". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Al-Jallad, Ahmad. "One wāw to rule them all: the origins and fate of wawation in Arabic and its orthography". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The people of the Thicket: Evidence for multiple scribes of a single Archetypal Quranic Text". Phoenix's blog. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- "Can you see the verb 'to see'?". Phoenix's blog. Retrieved 2017-08-14.