Odontocyclops

Odontocyclops : Greek: ondont-“tooth” Greek: kyklops- “round eye”, a kind of Greek mythological giant with one eye in the midline” =toothy cyclops.[1] The Odontocyclops is an extinct genus of Dicynodonts that lived in the Late Permian. Dicynodonts are believed to be the first major assemblage of terrestrial herbivores.[2] Fossils of Odontocyclops have been found in the Karoo Basin of South Arfrica and the Luangwa Valley of Zambia.[2] The phylogenetic classification of Odontocyclops has been long under debate, but most current research places them as their own genus of Dicynodonts and being very closely related to Rhachiocephalus and Oudenodon.[2]

| Odontocyclops | |

|---|---|

| Skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | †Dicynodontia |

| Clade: | †Cryptodontia |

| Genus: | †Odontocyclops Keyser and Cruickshank 1979 |

Discovery and classification

The first skull of what would later be named, Odontocyclops, was discovered in 1913 by Rev. J.H White in the Karoo Basin of South Africa. In 1938, additional Odontocyclops specimens were discovered in the Luangwa Valley of Zambia. Using these specimens and a few later collected skulls Cruickshank and Keyser in their 1979 paper erected a new genus of Dicynodonts to accommodate Odontocyclops.[1] However, Culver and King did not believe that the diagnostic features listed by Cruickshank and Keyser (1979) distinguished Odontocyclops from the genus Dicynodon.[3] This later lead King to classify Odontocylops, not as its own genus, but as a synonym for Dicynodon.[4] However, the most current research by Angielczyk has used cladistic data and provided the most current suggested hypothesis that Odontocyclops represents its own genus of Dicynodont and is very closely related to Rhachiocephalus and Oudenodon.[2]

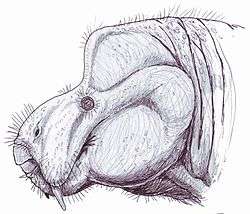

Description

Odontocyclops is distinguished from other dicynodonts by two autapomorphies: elongated nasal bosses and concave dorsal surface of the snout.[2]Odontocyclops also possesses wide exposure of the parietals on the intertemporal skull roof, the presence of a postcaniniform crest, the absence of a labial fossa, and the presence of a dorsal process on the anterior ramus of the epipterygoid footplate.[2]

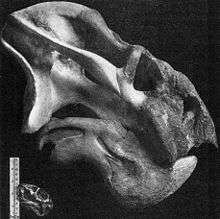

Skull

The skull of Odontocyclops are large compared to other dicynodonts, measuring 60 cm and greater.[1] Large canine tusks are found in some of the specimens, but not others. However, the presence of tusks appears to be variable and not correlated with size. Consequently, it is reasoned that the presence of tusks is not a sexual dimorphism for this genus.[1] The overall shape of the skull is very similar to that of Rhachiocepalus. In dorsal view the snout is notably concave and is formed by large nasal bosses that project medially over the snout.[2] The bone that forms these nasal bosses is covered with numerous fine pits, suggesting the presence of a keratin covering. Additionally, all known specimens lack premaxillary teeth. This combined with other evidence points towards Odontocyclops possessing a keratinous beak. Lastly, the vomers of Odontocyclops are fused and they do possess a secondary palate that is relatively flat compared to other dicynodonts and contains low walls.[2]

Jaw

The jaws of the available specimen for examination are poorly preserved. The jaw that has been examined for Odontocyclops, only has preservation of the anterior portion of the jaw. From this available information it was determined that Odontocyclops lack denary teeth, but do contain a lateral dentary shelf.[2] The presence of the lateral dentary shelf combined with the quadrates being similar in morphology to other dicynodonts suggest that Odontocyclops used a propalinal sliding feeding mechanism.[2]

Pineal eye?

Its skull clearly had two normal eyes, but the wide open pineal foramen shows that it also had a "pineal eye". In reptiles, the pineal organ senses changes in temperature and light.

Humerus

There is only a single left humerus available for examination of Odontocyclops. This humerus possesses largely expanded proximal and distal ends, which are separated by a short shaft.[2] The proximal and distal ends of the humerus are offset by 40 degrees. The proximal portion of the humerus is relatively flat, whereas, the distal potion is convex. The peak of this convexity is at the distal end of the humeral head.[2]

Scapula

Only one left scapula was available for examination of Odontocyclops. This scapula is similar to the scapula of other dicynodonts and consists of a long, curved, spatulate, dorsally expanded blade that arises from a robust, rounded base.[2] The medial surface of the Odontocyclops scapula blade is relatively smooth and slightly concave. From this specimen there is no evidence that Odontocyclops had a cleithrum.[2] Additionally, the scapula and coracoid remain separate and are not fused. This lack of fusion is a feature that is seen in other dicynodonts.[2]

Paeloenvironment and paleobiology

Environment

Odontocyclops specimens have been found both in the Karoo Basin of South Africa and the Madumabisa Mudstone of the Luangwa Valley of Zambia.[2] The Karoo Basin was originally formed in the Late Carboniferous resulting from the collision of the paleo-Pacific plate with the Gondwanan plate.[5] The Karoo Basin and Luangwa Valley have yielded a large number of dicynodonts. Their ancient ecosystems occupied a region of low-lying flood plains cut by a series of extensive braided river channels.[6] The Madumabisa Mudstone, within which, Odontocyclops was found is a formation that is 700 meters thick. It is believed to be formed from sediment deposits of massive mudrock, deposited from sediment rich rivers entering a lake. The Madumabisa Mudstone is a grey/greenish color, but other colors ranging from brownish grey to dark green and red are present.[7]

Diet

Dicynodonts are considered to be the first successful terrestrial herbivores.[8] The Odontocyclops diet most likely consisted of a variety of seeds, leaves, stems, and fleshy parts of plants.[8] It is likely that they possessed a feeding behavior similar to one of their closest relatives, Oudenodon, which had a more upright stance and moved rather slowly. They most likely possessed a browsing feeding behavior, eating vegetation that was 20–100 cm above the ground.[9] Their propalinal sliding mechanism of feeding combined with their sharp keratin beak provided a sharp surface to efficiently cut and grind plant material.[9]

Growth

There exists little information of the specific growth patterns of Odontocyclops. However, by examining general dicynodont growth patterns, an understanding of a similar patterns can be inferred for Odontocyclops. Dicynodonts are characterized by a predominance of fibrolamellar bone tissue in the cortex. Fibroamellar bone is associated with rapid osteogenesis, therefore, it is suggested that dicynodonts exhibited fast bone growth.[10] Another pattern of growth in some dicynodonts, including the closest relatives of Odontocyclops, is rapid growth as a juvenile followed by a decrease in growth rate with age.[10] Once again, the available specimen sample size is too small to make definite conclusions about growth patterns of Odontocyclops. However, one of the specimens presumed to be a juvenile is lacking large nasal bosses, suggesting that this is a feature obtained later in life.[2]

See also

References

- Keyser, A. W., and A. R. I. Cruickshank. 1979. The origins and classification of Triassic Dicynodonts. Transactions of the Geological Society of South Africa, 12:1-35.

- Angielczyk, K. D. 2002. Redescription, phylogenetic position, and stratigraphic significance of the dicynodont genus Odontocyclops (Synap-sida: Anomodontia). Journal of Paleontology 76:1047–1059.

- Cluver, M. A., and G.M. King. 1983. A reassessment of the relationships of Permian Dicynodontia (Reptilia, Therapsida) and a new classification of dicynodonts. Annals of the South African Museum, 91: 195-273.

- King, G. M. 1988. Anomodontia. Handbuch der Palaoherpetologie. Teil 17C, Fischer, Stuttgart, 174 p.

- Smith, R. M. H. 1995. Changing fluvial environments across the Permian-Triassic boundary in the Karoo basin, S. Africa and possible causes of tetrapod extinctions. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 117, 81–104.

- Jasinoski, S. C., Rayfield, E. J. and Chinsamy, A. (2009), Comparative Feeding Biomechanics of Lystrosaurus and the Generalized Dicynodont Oudenodon. Anat Rec, 292: 862–874.

- Nyambe, I.A., Dixon, O., 2000. Sedimentology of the Madumabisa Mudstone Formation (Late Permian), Lower Karoo Group, mid-Zambezi Valley Basin, southern Zambia. Journal of African Earth Sciences 30, 535e553.

- King, G. (1993). Species longevity and generic diversity in dicynodont mammal-like reptiles. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 102(3), 321-332.

- Sullivan, C. S. (2000). Cranial anatomy of the late permian dicynodont diictodon , and its bearing on aspects of the taxonomy, palaeobiology and phylogenetic relationships of the genus (Order No. MQ54209). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304663112).

- Chinsamy-Turan, A. (2012). Forerunners of Mammals : Radiation, Histology, Biology (Life of the past). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.