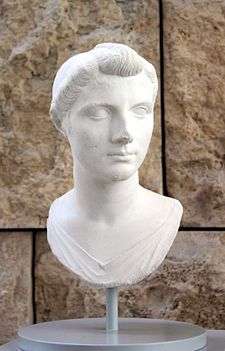

Octavia the Younger

Octavia the Younger (Latin: Octavia Minor ; 69–11 BC) was the elder sister of the first Roman Emperor, Augustus (known also as Octavian), the half-sister of Octavia the Elder, and the fourth wife of Mark Antony. She was also the great-grandmother of the Emperor Caligula and Empress Agrippina the Younger, maternal grandmother of the Emperor Claudius, and paternal great-grandmother and maternal great-great-grandmother of the Emperor Nero.

| Octavia Minor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 69 BC Nola, Roman Republic |

| Died | 11 BC (aged 58) Rome, Roman Empire |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Gaius Claudius Marcellus (consul 50 BC) Mark Antony |

| Issue | Marcus Claudius Marcellus Claudia Marcella Major Claudia Marcella Minor Antonia Major Antonia Minor |

| House | Octavia (gens) |

| Father | Gaius Octavius |

| Mother | Atia Balba Caesonia |

One of the most prominent women in Roman history, Octavia was respected and admired by contemporaries for her loyalty, nobility and humanity, and for maintaining traditional Roman feminine virtues.

Life

Childhood

Full sister to Augustus, Octavia was the only daughter born of Gaius Octavius' second marriage to Atia Balba Caesonia, niece of Julius Caesar.[1] Octavia was born in Nola, present-day Italy; her father, a Roman governor and senator, died in 59 BC from natural causes. Her mother later remarried, to the consul Lucius Marcius Philippus. Octavia spent much of her childhood travelling with her parents. Marcius was in charge of educating Octavia and her brother Octavian, later known as Augustus.[2]

First marriage

Before 54 BC, her stepfather arranged for her to marry Gaius Claudius Marcellus (consul 50 BC). Marcellus was a man of consular rank, a man who was considered worthy of her and was consul in 50 BC. He was also a member of the influential Claudian family and descended from Marcus Claudius Marcellus, a famous general in the Second Punic War. In 54 BC, her great uncle Caesar is said to have been anxious for her to divorce her husband so that she could marry Pompey who had just lost his wife Julia (Julius Caesar's daughter, and thus Octavia's cousin once removed). The couple did not want to get a divorce so instead[2] Pompey declined the proposal[3] and married Cornelia Metella. So Octavia's husband continued to oppose Julius Caesar including in the crucial year of his consulship 50 BC. Civil war broke out when Caesar invaded Italy from Gaul in 49 BC.[2]

Marcellus, a friend of Cicero, was an initial opponent of Julius Caesar when Caesar invaded Italy, but did not take up arms against his wife's great uncle at the Battle of Pharsalus, and was eventually pardoned by him. In 47 BC he was able to intercede with Caesar for his cousin and namesake, also a former consul, then living in exile. Presumably, Octavia continued to live with her husband from the time of their marriage (she would have been about 15 when they married) to her husband's death when she was about 29. They had three surviving children: Claudia Marcella Major, Claudia Marcella Minor and Marcus Claudius Marcellus.[4] All three were born in Italy. Although according to the anonymous Περὶ τοῦ καισαρείου γένους Octavia bore Marcellus four sons and four daughters.[5][6] Her husband Marcellus died in May 40 BC.

Second marriage

By a Senatorial decree, Octavia married Mark Antony in October 40 BC, as his fourth wife (his third wife Fulvia having died shortly before). This marriage had to be approved by the Senate, as she was pregnant with her first husband's child, and was a politically motivated attempt to cement the uneasy alliance between her brother Octavian and Mark Antony; however, Octavia does appear to have been a loyal and faithful wife to Antony.[7] Between 40 and 36 BC, she travelled with Antony to various provinces and lived with him in his Athenian mansion.[8] There she raised her children by Marcellus as well as Antony's two sons; Antyllus and Iullus, as well as the two daughters of her marriage to Antony, Antonia Major and Antonia Minor who were born there.

Breakdown

The alliance was severely tested by Antony's abandonment of Octavia and their children in favor of his former lover Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt (Antony and Cleopatra had met in 41 BC, an interaction that resulted in Cleopatra bearing twins, a boy and a girl). After 36 BC, Octavia returned to Rome with the daughters of her second marriage. On several occasions she acted as a political advisor and negotiator between her husband and brother.[9] For example, in the spring of 37 BC, while pregnant with her daughter Antonia Minor, she was considered essential to an arms deal held at Tarentum, in which Antony and Augustus agreed to aid each other in their Parthian and Sicilian campaigns. She was hailed as a "marvel of womankind."[10] In 35 BC, after Antony suffered a disastrous campaign in Parthia, she brought fresh troops, provisions, and funds to Athens. There Antony had left a letter for her, instructing her to go no further.[11] Mark Antony divorced Octavia in late 33 BC.[12] Following Antony's rejection of her and their divorce, Octavia became sole caretaker of their children.[13] She took his sons Antyllus and Iullus with her when she left Antony's house in 33. He had to sue her for custody and won back his sons, but not their daughters. After Antony's suicide in 30 BC, her brother executed Antyllus but allowed Octavia to raise Iullus and Antony's children by Cleopatra: The two sons Alexander Helios and Ptolemy Philadelphus, and one daughter, Cleopatra Selene II.

Later life

In 35 BC Augustus accorded a number of honours and privileges to Octavia, and Augustus' wife Livia, previously unheard of for women in Rome. They were granted sacrosanctitas, meaning it was illegal to verbally insult them. Previously, this had been only granted to tribunes. Livia and Octavia were made immune from tutela, the male guardianship which all women in Rome except for the Vestal Virgins were required to have. This meant they could freely manage their own finances. Finally, they were the first women in Rome to have statues and portraits displayed en masse in public places. Previously, only one woman, Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, had been part of the public statues displayed in Rome. In Augustus' rebuilding of Rome as a city of marble, Octavia was featured. In all her representations she wore the "nodus" hairstyle, which at the time was considered conservative and dignified, and worn by women from many classes.[14]

Augustus adored, but never adopted, her son Marcellus. When Marcellus died of illness in 23 BC unexpectedly, Augustus was thunderstruck, Octavia disconsolate almost beyond recovery.

Aelius Donatus, in his Life of Vergil, states that Virgil

recited three whole books [of his Aeneid] for Augustus: the second, fourth, and sixth—this last out of his well-known affection for Octavia, who (being present at the recitation) is said to have fainted at the lines about her son, "… You shall be Marcellus" [Aen. 6.884]. Revived only with difficulty, she sent Virgil ten thousand sesterces for each of the verses."[15]

She may have never fully recovered from the death of her son and retired from public life,[16] except on important occasions. The major source that Octavia never recovered is Seneca (De Consolatione ad Marciam, II.) but Seneca may wish to show off his rhetorical skill with hyperbole, rather than adhere to fact. Some dispute Seneca's version, for Octavia publicly opened the Library of Marcellus, dedicated in his memory, while her brother completed the Marcellus's theatre in his honor. Undoubtedly Octavia attended both ceremonies, as well as the Ara Pacis ceremony to welcome her brother's return in 13 from the provinces. She was also consulted in regard to, and in some versions advised, that Julia marry Agrippa after her mourning for Marcellus ended. Agrippa had to divorce Octavia's daughter Claudia Marcella Major in order to marry Julia, so Augustus wanted Octavia's endorsement very much.

Death

Octavia died of natural causes. Suetonius says she died in Augustus' 54th year, thus 11 BC with Roman inclusive counting.[17] Her funeral was a public one, with her sons-in-law (Drusus, Ahenobarbus, Iullus Antony, and possibly Paullus Aemillius Lepidus) carrying her to the grave in the Mausoleum of Augustus. Drusus delivered one funeral oration from the rostra; Augustus the other and gave her the highest posthumous honors (e.g. building the Gate of Octavia and Porticus Octaviae in her memory).[18] Augustus also had the Roman senate declare his sister to be a goddess.[19] Augustus declined some other honors decreed to her by the senate, for reasons unknown.[18] She was one of the first Roman women to have coins minted bearing her image; only Antony's previous wife Fulvia pre-empted her.

Issue

- Children with Marcellus

Octavia and her first husband had one son and two daughters born late in their marriage:

- Marcellus

- Claudia Marcella Major

- Claudia Marcella Minor

- Children with Mark Antony

Octavia and Mark Antony had two daughters by their marriage (her second, his fourth), and both were the ancestors of later Roman emperors.

- Antonia Major: also known as Julia Antonia Major,[20] grandmother to Emperor Nero.

- Antonia Minor: also known as Julia Antonia Minor,[20] mother to Emperor Claudius, grandmother to Emperor Caligula, and great-grandmother to Emperor Nero.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Octavia the Younger | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Descendants

Three Roman emperors, Caligula, Claudius and Nero, were amongst the most famous of her descendants.

- Octavia the Younger

- Marcus Claudius Marcellus (42 BC – 23 BC), no issue

- Claudia Marcella Major (born 41 BC)

- Vipsania Marcella Major

- Vipsania Marcella Minor

- Lucius Antonius (20 BC – AD 25), no issue

- Gaius Antonius (? – ?), issue unknown

- Iulla Antonia (after 19 BC – ?), issue unknown

- Claudia Marcella Minor (born 40 BC)

- Paullus Aemilius Regulus (? – ?), issue unknown

- Claudia Pulchra (14 BC–26)

- Marcus Valerius Messala Barbatus (11 BC – 20/21)

- Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus (? – ?), possibly son of Aurelius Messalinus

- Valeria Messalina (17 AD or 20 AD – 48 AD)

- Claudia Octavia (39 AD or 40 AD – 62 AD), no issue

- Tiberius Claudius Caesar Britannicus (41 AD – 55 AD), no issue

- Valeria Messallia (c. 10 BC – ?)

- Lucius Vipstanus Poplicola (c. 10 – after 59)

- Gaius Valerius Poplicola (? – ?), issue unknown

- Gaius Vipstanus Messalla Gallus[21] (c. 10 BC – after 60)

- Lucius Vipstanus Messalla[21] (c. 45 – c. 80)

- Lucius Vipstanus Poplicola (c. 10 – after 59)

- Julia Antonia Major (39 BC – before 25 AD)

- Domitia Lepida the Elder (c. 19 BC – 59 AD)

- Quintus Haterius Antoninus (? – ?)

- Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus (17 BC – 40 AD)

- Claudia Augusta (January 63 AD – April 63 AD), died young

- Domitia Lepida the Younger (10 BC – 54 AD)

- Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus (same man as above), possibly son of Aurelius Messalinus or Valerius Barbatus (same man as above)

- Valeria Messalina (same woman as above)

- See her line above

- Faustus Cornelius Sulla Felix (22 AD – 62 AD)

- A son, died young

- Domitia Lepida the Elder (c. 19 BC – 59 AD)

- Julia Antonia Minor (36 BC – 37 AD)

- Germanicus Julius Caesar (15 BC – 19 AD)

- Nero Julius Caesar Germanicus (6 AD – 30 AD), no issue

- Drusus Julius Caesar Germanicus (8 AD – 33 AD), no issue

- Tiberius Julius Caesar Germanicus (born between 7 and 12 AD), died as an infant

- Ignotus (born between 7 and 12 AD), died as an infant

- Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus Major (born between 7 and 12 AD), died in childhood

- Julia Drusilla (39 AD – 41 AD), died young

- Julia Agrippina (Agrippina Minor) (15 AD – 59)

- Julia Drusilla (16 AD – 38 AD), no issue

- Julia Livilla (18 AD – 42 AD), no issue

- Claudia Livia Julia (Livilla) (13 BC – 31 AD)

- Julia Livia (7 AD – 43 AD)

- Gaius Rubellius Plautus (33 AD – 62 AD), had several children[n 1]

- Rubellia Bassa (born between 33 AD and 38 AD)[n 2]

- Octavius Laenas (? – ?)

- Gaius Rubellius Blandus (? – ?), issue unknown

- Rubellius Drusus (? – ?), issue unknown

- Tiberius Julius Caesar Nero Gemellus (19AD – 37 AD or 38 AD), no issue

- Tiberius Claudius Caesar Germanicus II Gemellus (19 AD – 23 AD), died young

- Julia Livia (7 AD – 43 AD)

- Tiberius Claudius Drusus, died young

- Claudia Antonia (c. 30 AD – 66 AD)

- A son (same individual as above)

- Claudia Octavia (same woman as above)

- Tiberius Claudius Caesar Britannicus (same man as above)

- Germanicus Julius Caesar (15 BC – 19 AD)

Cultural depictions

A highly fictionalized version of Octavia's early life is depicted in the 2005 television series Rome, in which Octavia of the Julii (Kerry Condon) seduces and sleeps with her younger brother, Gaius Octavian, has a lesbian affair with Servilia of the Junii (the series' version of Servilia) and a romantic relationship with Marcus Agrippa (based on the historical Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa).

Octavia's later life, around the time of the death of Marcellus, is depicted in the 1976 television adaptation of Robert Graves's novel I, Claudius. The role was played by Angela Morant, and should not be confused with her great-granddaughter Claudia Octavia (also referred to as "Octavia" in the series), Claudius's daughter and wife of the future emperor Nero, who was played by Cheryl Johnson.

In the 1963 film Cleopatra, she is played by Jean Marsh in an uncredited role.[26]

Notes

- Their names are unknown, but it is known that all of them were killed by Nero, thus descent from this line is extinct.

- Sir Ronald Syme claims that Sergius Octavius Laenas Pontianus, consul in 131 under Emperor Hadrian, set up a dedication to his grandmother, Rubellia Bassa.

References

- Suetonius, Augustus 4.1

- "Octavia Minor - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- Suetonius, Caesar 27.1

- Suetonius, Augustus 63.1; Plutarch, Antony 87

- Spyridon Lambros, Ἀνέκδοτον ἀπόσπασμα συγγραϕῆς περὶ τοῦ Καισαρείου γένους, Νέος Ἑλληνομνήμων 1 (1904), p. 148

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/classical-quarterly/article/marcia-catonis-and-the-fulmen-clarum/786E542AA13E96391FB133D4AB8B369E

- Plutarch, Antony 31; Appian, Civil Wars 5.64 and 5.66; Cassius Dio, Roman History 48.31.3

- Plutarch, Antony 33; Appian, Civil Wars 5.76

- So at the treaty of Taranto in 37 BC: Plutarch, Antony 35; Appian, Civil Wars 5.93-95; Cassius Dio, Roman History 48.54

- Freisenbruch, Annelise (2010). The First Ladies of Rome: The Women behind the Caesars. London.

- Plutarch, Antony 53; Cassius Dio, Roman History 49.33.3-4. See also a modern source,Freisenbruch, Annelise (2010). The First Ladies of Rome: The Women behind the Caesars. London. pp. 30–37.

- Plutarch, Antony 57.4-5; Cassius Dio, Roman History 50.3.2

- Plutarch, Antony 87; Cassius Dio, Roman History 51.15.5

- Freisenbruch, Annelise (2010). The first ladies of rome: THe women behind the caesars. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 38.

- Life of Virgil

- "Octavia". Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Suet. Div. Aug. 61. A Roman child is 1 year old until its 365th day, when it becomes 2. Thus Augustus' 54th year = 10 BC, since he was born in 63. Note that Dio 54.35.4-5 is not datable.

- Dio 54.35.5

- "Octavia". virtualreligion.net. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- Minto, The Heliopolis Scrolls, p.159

- Syme, Ronald. The Augustan Aristocracy (1986), pg. 242

- Mennen, Inge. Power and Status in the Roman Empire, AD 193-284 (2011), pg. 123-124-125-127.

- Settipani, Christian. Continuité gentilice et continuité sénatoriale dans les familles sénatoriales romaines à l'époque impériale (2000), pgs. 227-228-229.

- Potter, David S., The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395 (2004), pg. 389

- Schlitz, Carl. "St. Melania (the Younger)." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 15 Mar. 2013

- Cleopatra (1963) film full cast list, BFI

Further reading

- Life and virtues

- Details on Octavia pt 1 "Octavian was much attached to his sister, and she possessed all the charms, accomplishments and virtues likely to fascinate the affections and secure a lasting influence over the mind of a husband. Her beauty was universally allowed to be superior to that of Cleopatra and her virtue was such as to excite even admiration in an age of growing licentiousness and corruption."

- Details on Octavia pt 2

- Nuttall Encyclopedia profile says merely that she was "distinguished for her beauty and her virtue"

- Discussion

- Family and descendants

- Print sources

- Cluett, Ronald. “Roman women and triumviral politics, 43-37 B.C.” Echos du monde classique. Classical views 17, no. 1 (1998), 67–84.

- Erhart, K. P. “A new portrait type of Octavia Minor (?).” The J. Paul Getty Museum journal 8 (1980), 117–28.

- Fischer. Fulvia und Octavia: die beiden Ehefrauen des Marcus Antonius in den politischen Kämpfen der Umbruchszeit zwischen Republik und Principat. Berlin: Logos-Verl., 1999.

- Foubert, Lien. “Vesta and Julio-Claudian women in imperial propaganda.” Ancient society 45 (2015), 187–204.

- Freisenbruch, Annelise. 2010. The First ladies of Rome: the women behind the Caesars. London: Jonathan Cape.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Octavia. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Octavia Minor. |

| Library resources about Octavia the Younger |

- Octavia entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

- Livius.org: Octavia Minor