Ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).[1]

.jpg)

Cargo vessels running to a schedule are sometimes called liners.[2] The category does not include ferries or other vessels engaged in short-sea trading, nor dedicated cruise ships where the voyage itself, and not transportation, is the prime purpose of the trip. Nor does it include tramp steamers, even those equipped to handle limited numbers of passengers. Some shipping companies refer to themselves as "lines" and their container ships, which often operate over set routes according to established schedules, as "liners".

Ocean liners are usually strongly built with a high freeboard to withstand rough seas and adverse conditions encountered in the open ocean. Additionally, they are often designed with thicker hull plating than is found on cruise ships, and have large capacities for fuel, food and other consumables on long voyages.[3]

The first ocean liners were built in the mid-19th century. Technological innovations such as the steam engine and steel hull allowed larger and faster liners to be built, giving rise to a competition between world powers of the time, especially between the United Kingdom and Germany. Once the dominant form of travel between continents, ocean liners were rendered largely obsolete by the emergence of long-distance aircraft after World War II. Advances in automobile and railway technology also played a role. After RMS Queen Elizabeth 2 was retired in 2008, the only ship still in service as an ocean liner is the RMS Queen Mary 2. Of the many ships constructed over the decades, only nine ocean liners made before 1967 survive.

Overview

Ocean liners were the primary mode of intercontinental travel for over a century, from the mid-19th century until they began to be supplanted by airliners in the 1950s. In addition to passengers, liners carried mail and cargo. Ships contracted to carry British Royal Mail used the designation RMS. Liners were also the preferred way to move gold and other high-value cargoes.[4]

The busiest route for liners was on the North Atlantic with ships travelling between Europe and North America. It was on this route that the fastest, largest and most advanced liners travelled, though most ocean liners historically were mid-sized vessels which served as the common carriers of passengers and freight between nations and among mother countries and their colonies and dependencies in the pre-jet age. Such routes included Europe to African and Asian colonies, Europe to South America, and migrant traffic from Europe to North America in the 19th and first two decades of the 20th centuries, and to Canada and Australia after the Second World War.

Shipping lines are companies engaged in shipping passengers and cargo, often on established routes and schedules. Regular scheduled voyages on a set route are called "line voyages" and vessels (passenger or cargo) trading on these routes to a timetable are called liners. The alternative to liner trade is "tramping" whereby vessels are notified on an ad-hoc basis as to the availability of a cargo to be transported. (In older usage, "liner" also referred to ships of the line, that is, line-of-battle ships, but that usage is now rare.) The term "ocean liner" has come to be used interchangeably with "passenger liner", although it can refer to a cargo liner or cargo-passenger liner.

Beginning at the advent of the Jet Age, where transoceanic ship service declined, a gradual transition from passenger ships as mean of transportation to nowadays cruise ships started.[5] In order for ocean liners to remain profitable, cruise lines have modified some of them to operate on cruise routes, such the SS France. Certain characteristics of older ocean liners made them unsuitable for cruising, such as high fuel consumption, deep draught preventing them from entering shallow ports, and cabins (often windowless) designed to maximize passenger numbers rather than comfort. The Italian Line's SS Michelangelo and SS Raffaello, the last ocean liners to be built primarily for crossing the North Atlantic, could not be converted economically and had short careers.[6]

History

19th century

.jpg)

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution and the inter-continental trade rendered the development of secure links between continents imperative. Being at the top among the colonial powers, the United Kingdom needed stable maritime routes to connect different parts of its empire: the Far East, India, Australia, etc.[7] The birth of the concept of international water and the lack of any claim to it simplified navigation.[8] In 1818, the Black Ball Line, with a fleet of sailing ships, offered the first regular passenger service with emphasis on passenger comfort, from England to the United States.[9]

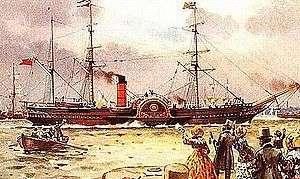

In 1807, Robert Fulton succeeded in applying steam engines to ships. He built the first ship that was powered by this technology, the Clermont, which succeeded in traveling between New York City and Albany, New York in thirty hours before entering into regular service between the two cities.[10] Soon after, other vessels were built using this innovation. In 1816, the Élise became the first steamship to cross the English Channel.[11] Another important advance came in 1819. SS Savannah became the first steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean. She left the city of the same name and arrived in Liverpool, England in 27 days. Most of the distance was covered by sailing; the steam power was not used for more than 72 hours during the travel.[12] The public enthusiasm for the new technology was not high, as none of the thirty-two people who had booked a seat on board boarded the ship for that historic voyage.[13] Although Savannah had proven that a steamship was capable of crossing the ocean, the public was not yet prepared to trust such means of travel on the open sea, and, in 1820, the steam engine was removed from the ship.[12]

Work on this technology continued and a new step was taken in 1833. Royal Edward managed to cross the Atlantic by using steam power on three-quarter of the course. The sail was used only when the wall of the boilers was cleaned.[12] There were still many skeptics, and in 1836, scientific writer Dionysius Lardner declared that:

As the project of making the voyage directly from New York to Liverpool, it was perfectly chimerical, and they might as well talk of making the voyage from New York to the moon.[14]

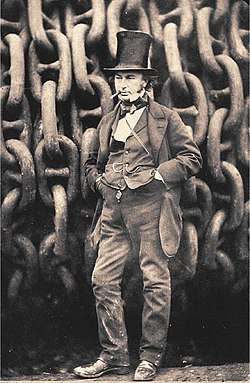

The last step toward long-distance travel using steam power was taken in 1837 when SS Sirius left Liverpool on April 4 and arrived in New York eighteen days later on April 22 after a turbulent crossing. Too little coal was prepared for the crossing, and the crew had to burn cabin furniture in order to complete the voyage. The journey took place at a speed of 8.03 knots.[15] The voyage was made possible by the use of a condenser, which fed the boilers with fresh water, avoiding having to periodically shut down the boilers in order to remove the salt.[14] The feat was short-lived. The next day, SS Great Western, designed by railway engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, arrived in New York. She left Liverpool on April 8 and overtook Sirius′s record with an average speed of 8.66 knots. The race of speed was commenced, and, with it, the tradition of the Blue Riband.[16]

With Great Western, Isambard Kingdom Brunel laid the foundations for new shipbuilding techniques. He realised that the carrying capacity of a ship increases as the cube of its dimensions, whilst the water resistance only increases as the square of its dimensions. This means that large ships are more fuel-efficient, something very important for long voyages across the Atlantic.[14][17] Constructing large ships was therefore more profitable.[18] Moreover, migration to the Americas increased enormously. These movements of population were a financial windfall for the shipping companies,[19] some of the largest of which were founded during this time. Examples are the P&O of the United Kingdom in 1822 and the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique of France in 1855.[20]

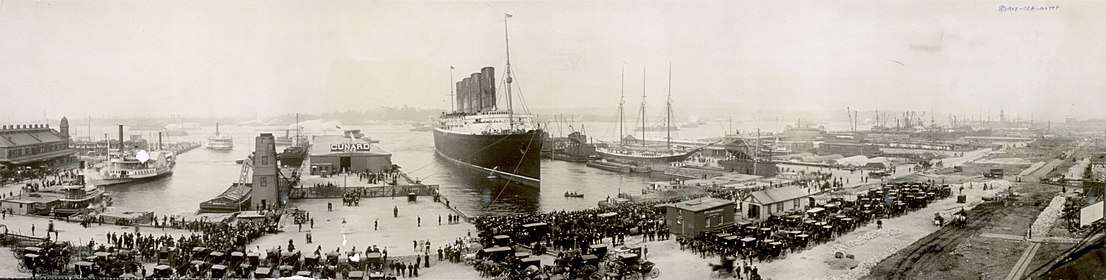

The steam engine also allowed ships to provide regular service without the use of sail. This aspect particularly appealed to the postal companies, which leased the services of ships to serve clients separated by the ocean. In 1839, Samuel Cunard founded the Cunard Line and became the first to dedicate the activity of his shipping company to the transport of mails, thus ensuring regular services on a given schedule. The company's vessels operated the routes between the United Kingdom and the United States.[21] Over time, the paddle wheel, impractical on the high seas, was abandoned in favour of the propeller.[10] In 1840, Cunard Line’s RMS Britannia began its first regular passenger and cargo service by a steamship, sailing from Liverpool to Boston.[22]

As the size of ship increased, the wooden hull became fragile. Beginning with the use of an iron hull in 1845, and then steel hulls, solved this problem.[23] The first ship to be both iron-hulled and equipped with a screw propeller was SS Great Britain, a creation of Brunel. Her career was disastrous and short. She was run aground and stranded at Dundrum Bay in 1846. In 1884, she was retired to the Falkland Islands where she was used as a warehouse, quarantine ship, and coal hulk until she was scuttled in 1937.[24] The American company Collins Line took a different approach. It equipped its ships with cold rooms, heating systems, and various other innovations but the operation was expensive. The sinking of two of its ships was a major blow to the company which was dissolved in 1858.[25]

In 1858, Brunel built his third and last giant, SS Great Eastern. The ship was, for 43 years, the largest passenger ship ever built. She had the capacity to carry 4,000 passengers.[26] Her career was marked by a series of failures and incidents, one of which was an explosion on board during her maiden voyage.[27]

Many ships owned by German companies like Hamburg America Line and Norddeutscher Lloyd were sailing from major German ports, such as Hamburg and Bremen, to the United States during this time. The year 1858 was marked by a major accident: the sinking of SS Austria. The ship, built in Greenock and sailing between Hamburg and New York twice a month, suffered an accidental fire off the coast of Newfoundland and sank with the loss of all but 89 of the 542 passengers.[28]

In the British market, Cunard Line and White Star Line (the latter after being bought by Thomas Ismay in 1868), competed strongly against each other in the late 1860s. The struggle was symbolised by the attainment of the Blue Riband, which the two companies achieved several times around the end of the century.[29] The luxury and technology of ships were also evolving. Auxiliary sails became obsolete and disappeared completely at the end of the century. Possible military use of passenger ships was envisaged and, in 1889, RMS Teutonic became the first auxiliary cruiser in history. In the time of war, ships could easily be equipped with cannons and used in cases of conflict. Teutonic succeeded in impressing Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany, who wanted to see his country endowed with a modern fleet.[30]

In 1870, the White Star Line’s RMS Oceanic set a new standard for ocean travel by having its first-class cabins amidships, with the added amenity of large portholes, electricity and running water.[31] The size of ocean liners increased from 1880 to meet the needs of immigration to the United States and Australia.

RMS Umbria[32] and her sister ship RMS Etruria were the last two Cunard liners of the period to be fitted with auxiliary sails. Both ships were built by John Elder & Co. of Glasgow, Scotland, in 1884. They were record breakers by the standards of the time, and were the largest liners then in service, plying the Liverpool to New York route.

SS Ophir was a 6814-ton[33] steamship owned by the Orient Steamship Co., and was fitted with refrigeration equipment. She plied the Suez Canal route from England to Australia during the 1890s, up until the years leading to World War I when she was converted to an armed merchant cruiser.

In 1897, Norddeutscher Lloyd launched SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. She was followed three years later by three sister ships. The ship was both luxurious and fast, managing to steal the Blue Riband from the British.[34] She was also the first of the fourteen ocean liners with four funnels that have emerged in maritime history. The ship needed only two funnels, but more funnels gave passengers a feeling of safety and power.[35] In 1900, the Hamburg America Line competed with its own four-funnel liner, SS Deutschland. She quickly obtained the Blue Riband for her company. This race for speed, however, was a detriment to passengers' comfort and generated strong vibration, which made her owner lose any interest in her after she lost the Blue Riband to another ship of Norddeutscher Lloyd.[36] She was only used for ten years for transatlantic crossing before being converted into a cruise ship.[37] Until 1907 the Blue Riband remained in the hands of the Germans.

Early 20th century

In 1902, J. P. Morgan embraced the idea of a maritime empire comprising a large number of companies. He founded the International Mercantile Marine Co., a trust which originally comprised only American shipping companies. The trust then absorbed Leyland Line and White Star Line.[38] The British government then decided to intervene in order to regain the ascendancy.

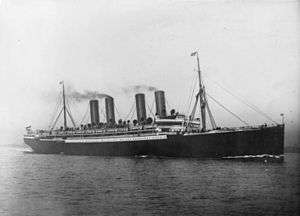

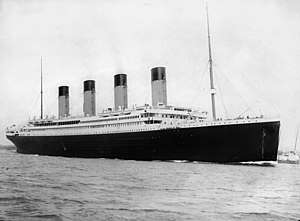

Although German liners dominated in terms of speed, British liners dominated in terms of size. RMS Oceanic and the Big Four of the White Star Line were the first liners to surpass SS Great Eastern as the largest passenger ships. Ultimately their owner was American (as mentioned above, White Star Line had been absorbed into J. P. Morgan's trust). Faced with this major competition, the British government contributed financially to Cunard Line's construction of two liners of unmatched size and speed, under the condition that they be available for conversion into armed cruisers when needed by the navy. The result of this partnership was the completion in 1907 of two sister ships: RMS Lusitania and RMS Mauretania, both of which won the Blue Riband during their respective maiden voyages. The latter retained this distinction for twenty years.[39] Their great speed was achieved by the use of turbines instead of conventional expansion machines.[40] In response to the competition from Cunard Line, White Star Line ordered the Olympic-class liners at the end of 1907.[41] The first of these three liners, RMS Olympic, completed in 1911, had a fine career, although punctuated by incidents. This was not the case for her sister, the RMS Titanic, which sank on her maiden voyage on 15 April 1912, resulting in several changes to maritime safety practices.[42] As for the Third Sister HMHS Britannic, she never served her intended purpose as a Passenger Ship, as She was drafted in World War 1 as a Hospital ship, and Sank to a Mine in 1916

At the same time, France tried to mark its presence with the completion in 1912 of SS France owned by the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique.[43] Germany soon responded to the competition from the British. From 1912 to 1914, Hamburg America Line completed a trio of liners significantly larger than the White Star Line's Olympic-class ships. The first to be completed, in 1913 was SS Imperator. She was followed by SS Vaterland in 1914.[44] The construction of the third liner, SS Bismarck, was paused by the outbreak of World War I.[45][46]

The First World War was a hard time for the liners. Some of them, like the Mauretania, Aquitania, and Britannic were transformed into hospital ships during the conflict.[39][47][48][43] Others became troop transports, while some, such as the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, participated in the war as warships.[49] Troop transportation was very popular due to the liners' large size. Liners converted into troop ships were painted in dazzle camouflage to reduce the risk of being torpedoed by enemy submarines.[50]

The war was marked by the loss of many liners. Britannic, while serving as a hospital ship, sank in the Aegean Sea in 1916 after she struck a mine.[51] Numerous incidents of torpedoing took place and large numbers of ships sank. Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was defeated and scuttled after a fierce battle with HMS Highflyer off the coast of west Africa, while her sister ship Kronprinz Wilhelm served as a commerce raider.[52] The torpedoing and sinking of RMS Lusitania on 7 May 1915 caused the loss of 128 American lives at a time when the United States was still neutral. Although other factors came into play, the loss of American lives in the sinking strongly pushed the United States to favour the Allied Powers and facilitated the country's entry into the war.[53]

The losses of the liners owned by the Allied Powers were compensated by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. This led to the awarding of many German liners to the victorious Allies. The Hamburg America Line's trio (Imperator, Vaterland, and Bismarck) were divided between the Cunard Line, White Star Line, and the United States Lines, while the three surviving ships of the Kaiser-class were requisitioned by the US Navy in the context of the conflict and then retained. The Tirpitz, whose construction was delayed by the outbreak of war eventually became the RMS Empress of Australia. Of the German superliners, only Deutschland, because of her poor state, avoided this fate.[37]

After World War I

After a period of reconstruction, the shipping companies recovered quickly from the damage caused by the First World War. The ships, whose construction was started before the war, such as SS Paris of the French Line, were completed and put into service.[54] Prominent British liners, such as the Olympic and the Mauretania, were also put back into service and had a successful career in the early 1920s. More modern liners were also built, such as SS Île de France (completed in 1927).[55] The United States Lines, having received the Vaterland, renamed her Leviathan and made her the flagship of the company's fleet. Because all U.S. registered ships counted as an extension of U.S. territory, the National Prohibition Act made American liners alcohol-free, causing alcohol-seeking passengers to choose other liners for travel and substantially reducing profits for the United States Lines.[44]

In 1929, Germany returned to the scene with the two ships of Norddeutscher Lloyd, SS Bremen and SS Europa. Bremen won the Blue Riband from Britain's Mauretania after the latter had held it for twenty years.[56] Soon, Italy also entered the scene. The Italian Line completed SS Rex and SS Conte di Savoia in 1932, breaking the records of both luxury and speed (Rex won the westbound Blue Riband in 1933).[57] France reentered the scene with SS Normandie of the French Line Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (CGT). The ship was the largest ship afloat at the time of her completion in 1932. She was also the fastest, winning the Blue Riband in 1935.[58]

A crisis arose when the United States drastically reduced its immigrant quotas, causing shipping companies to lose a large part of their income and to have to adapt to this circumstance.[59] The Great Depression also played an important role, causing a drastic decrease in the number of people crossing the Atlantic and at the same time reducing the number of profitable transatlantic voyages. In response, shipping companies redirected many of their liners to a more profitable cruise service.[60] In 1934, in the United Kingdom, Cunard Line and White Star Line were in very bad shape financially. Chancellor of the Exchequer Neville Chamberlain proposed to merge the two companies in order to solve their financial problems.[61] The merger took place in 1934 and launched the construction of the Queen Mary while progressively sending their older ships to the scrapyard. The Queen Mary was the fastest ship of her time and the largest for a short amount of time, she captured the Blue Riband twice, both off Normandie.[62] The construction of a second ship, the Queen Elizabeth, was interrupted by the outbreak of World War II.[63]

The Second World War was a conflict rich in events involving liners. From the start of the conflict, German liners were requisitioned and many were turned into barracks ships. It was in the course of this activity that the Bremen caught fire and was scrapped in 1941.[64] During the conflict, RMS Queen Elizabeth and RMS Queen Mary provided distinguished service as troopships.[65]

Many liners were sunk with great loss of life; in World War II the three worst disasters were the loss of the Cunarder Lancastria in 1940 off Saint-Nazaire to German bombing while attempting to evacuate troops of the British Expeditionary Force from France, with the loss of more than 3,000 lives;[66] the sinking of Wilhelm Gustloff, after the ship was torpedoed by a Soviet submarine, with more than 9,000 lives lost, making it the deadliest maritime disaster in history;[67] and the sinking of SS Cap Arcona with more than 7,000 lives lost, both in the Baltic Sea, in 1945.[68]

SS Rex was bombarded and sunk in 1942, while Normandie caught fire, capsized and sank in New York in 1942 while being converted for troop duty.[69] Many of the superliners of the 'twenties and 'thirties were victims of U-boats, mines or enemy aircraft. Empress of Britain was attacked by German planes, then torpedoed by a U-boat when tugs tried to tow her to safety.[70]

Decline of long-distance line voyages

.jpg)

After the war, some ships were again transferred from the defeated nations to the winning nations as war reparations. This was the case of the Europa, which was ceded to France and renamed Liberté.[71] The United States government was very impressed with the service of the Cunard's Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth as troopships during the war. To ensure a reliable and fast troop transport in case of a war against the Soviet Union, the U.S. government sponsored the construction of SS United States and entered it into service for the United States Lines in 1952. She won the Blue Riband on her maiden voyage in that year and held it until Richard Branson won it back in 1986 with Virgin Atlantic Challenger II.[72] One year later, in 1953, Italy completed the SS Andrea Doria, which later sank in 1956 after a collision with MS Stockholm.[73]

Before World War II, aircraft had not been a significant threat to ocean liners. Most pre-war aircraft were noisy, vulnerable to bad weather, few had the range needed for transoceanic flights, and all were expensive and had a small passenger capacity. The war accelerated development of large, long-ranged aircraft. Four-engined bombers, such as the Avro Lancaster and Boeing B-29 Superfortress, with their range and massive carrying capacity, were natural prototypes for post-war next-generation airliners. Jet engine technology also accelerated due to wartime development of jet aircraft. In 1953, the De Havilland Comet became the first commercial jet airliner; the Sud Aviation Caravelle, Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8 followed, and much long-distance travel was done by air. The Italian Line's SS Michelangelo and SS Raffaello,[6] launched in 1962 and 1963, were two of the last ocean liners to be built primarily for liner service across the North Atlantic. Cunard's transatlantic liner, Queen Elizabeth 2, was also used as a cruise ship.[5] By the early 1960s, 95% of passenger traffic across the Atlantic was by aircraft. Thus the reign of the ocean liners came to an end.[74] By the early 1970s, many passenger ships continued their service in cruising.

In 1982, during the Falklands War, three active or former liners were requisitioned for war service by the British Government. The liners Queen Elizabeth 2[75] and Canberra, were requisitioned from Cunard and P&O to serve as troopships, carrying British Army personnel to Ascension Island and the Falkland Islands to recover the Falklands from the invading Argentine forces. The P&O educational cruise ship and former British India Steam Navigation Company liner Uganda was requisitioned as a hospital ship, and served after the war as a troopship until the RAF Mount Pleasant station was built at Stanley, which could handle trooping flights.[76]

21st century

By the first decade of the 21st century, only a few former ocean liners were still in existence, some like SS Norway, were sailing as cruise ships while others, like Queen Mary, were preserved as museums, or laid up at pier side like SS United States. After the retirement of Queen Elizabeth 2 in 2008, the only ocean liner in service was Queen Mary 2, built in 2003–04, used for both point-to-point line voyages and for cruises.

Survivors

Four ocean liners that were made before World War II survive today as they have been preserved as museums, and hotels. The Japanese ocean liner Hikawa Maru, has been preserved in Naka-ku, Yokohama, Japan, as a museum ship, since 1961. RMS Queen Mary was preserved in 1967 after her retirement, and became a museum/hotel in Long Beach, California. In the 1970s, SS Great Britain was also preserved, and now resides in Bristol, England as another museum.[77] The latest ship to undergo preservation is MV Doulos, which is to become a dry berthed hotel on Bintan Island, Indonesia.[78][79]

Post-war ocean liners that are preserved are United States (1952), docked in Philadelphia since 1996; Rotterdam (1958), moored in Rotterdam as a museum and hotel since 2008;[80] and Queen Elizabeth 2 (1967), floating luxury hotel and museum at Mina Rashid, Dubai since 2018.[81]

Two former ocean liners remain in service as cruise ships, operating under Cruise & Maritime Voyages: Marco Polo (1965) (formerly MS Alexandr Pushkin),[82] and MV Astoria (1948) (originally MS Stockholm, which collided with Andrea Doria in 1956).[83]

Characteristics

Size and speed

Since their beginning in the 19th century, ocean liners must meet growing demands. The first liners were small and overcrowded, leading to unsanitary conditions on board.[19] Eliminating these phenomena required larger ships, to reduce the crowding of passengers, and faster ships, to reduce the duration of transatlantic crossings. The iron and steel hulls and steam power allowed for these advances. Thus, SS Great Western (1,340 GRT) and SS Great Eastern (18,915 GRT) were constructed in 1838 and 1858 respectively.[26] The record set by Great Eastern was not beaten until 43 years later in 1901 when RMS Celtic (20,904 GT) was completed.[84] The tonnage then grew profoundly: the first liners to have a tonnage that exceeded 20,000 were the Big Four of the White Star Line. The Olympic-class ocean liners, first completed in 1911, were the first to have a tonnage that exceeded 45,000. SS Normandie, completed in 1935, had a tonnage of 79,280.[85] In 1940, RMS Queen Elizabeth raised the record of size to a tonnage of 83,673. She was the largest passenger ship ever constructed until 1997.[86] In 2003, RMS Queen Mary 2 became the largest, at 149,215 GT.

In the early 1840s, the average speed of liners was less than 10 knots (a crossing of the Atlantic thus took about 12 days or more). In the 1870s, the average speed of liners increased to around 15 knots the duration of a transatlantic crossing shortened to around 7 days, owing to the technological progress made in the propulsion of ships: the rudimentary steam boilers gave rise to more elaborate machineries and the paddlewheel gradually disappeared, replaced first by one helix then by two helixes. At the beginning of the 20th century, Cunard Line's RMS Lusitania and RMS Mauretania reached a speed of 27 knots. Their records seemed unbeatable, and most shipping companies abandoned the race for speed in favor of size, luxury, and safety.[29] The advent of ships with diesel engines, and of those whose engines were oil-burning, such as the Bremen, in the early 1930s, relaunched the race for the Blue Riband. The Normandie won it in 1935 before being snatched by RMS Queen Mary in 1938. It was not until 1952 that SS United States set a record that remains today: 34.5 knots (3 days and 12 hours of crossing the Atlantic).[29] In addition, since 1935, the Blue Riband is accompanied by the Hales Trophy, which is awarded to the winner.[87]

Passenger cabins and amenities

The first ocean liners were designed to carry mostly migrants. On-board sanitary conditions were often deplorable and epidemics were frequent. In 1848, maritime laws imposing hygiene rules were adopted and they improved on-board living conditions.[88] Gradually, two distinct classes were developed: the cabin class and the steerage class. The passengers traveling on the former were wealthy passengers and they enjoyed certain comfort in that class. The passengers traveling on the latter were members of the middle class or the working class. In that class, they were packed in large dormitories. Until the beginning of the 20th century, they did not always have bedsheets and meals.[89] An intermediate class for tourists and members of the middle class gradually appeared. The cabins were then divided into three classes.[40] The facilities offered to passengers developed over time. In the 1870s, the installation of bathtubs and oil lamps caused a sensation on board RMS Oceanic.[90] In the following years, the number of amenities became numerous, for example: smoking rooms, lounges, and promenade deck. In 1907, RMS Adriatic even offered turkish baths and a swimming pool.[91] In the 1920s, SS Paris was the first liner to offer a movie theatre.[92]

A first-class cabin on board Titanic in 1912

A first-class cabin on board Titanic in 1912 The second class smoking room on board Mauretania

The second class smoking room on board Mauretania The first class dining room on board Queen Mary

The first class dining room on board Queen Mary

Builders and shipping companies

Shipyards

British and German

The British and the Germans were the most famed in shipbuilding during the great era of ocean liners. In Ireland, Harland & Wolff shipyard of Belfast were particularly innovative and succeeded in winning the trust of many shipping companies, such as White Star Line. These gigantic shipyards employed a large portion of the population of cities and built hulls, machines, furnitures and lifeboats.[93] Among the other well-known British shipyards were Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson, the builder of RMS Mauretania, and John Brown & Company, builder of RMS Lusitania.[94]

Germany had many shipyards on the coast of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, including Blohm & Voss and AG Vulcan Stettin. Many of these shipyards were destroyed during World War II; some managed to recover and continue building ships.[95]

Other nations

In France, major shipyards included Chantiers de Penhoët in Saint-Nazaire, known for building SS Normandie.[96] This shipyard merged with Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire shipyard to form the Chantiers de l'Atlantique shipyard, which has built ships including RMS Queen Mary 2.[97] France also had major shipyards on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea.[98]

Italy and the Netherlands also had shipyards capable of building large ships (for example, Fincantieri).[99]

Shipping companies

British

There were many British shipping companies; two were particularly distinguished: Cunard Line and White Star Line. Both were founded during the 1830s and engaged in strong competition against one another, possessing the largest and fastest liners in the world in the early 20th century. It was not until 1934 that financial difficulty caused the two to merge, forming Cunard White Star Ltd.[100] The P&O also occupied a large part of the business.

The Royal Mail Steam Packet Company operated as a state-owned enterprise with its close relationship with the government. Over the course of its history, it took over many shipping companies, becoming one of the largest companies in the world before legal problems led to its liquidation in 1931. The Union Castle Line operated in Africa and the Indian Ocean with a fleet of considerable size.[101]

German and French

Two rival companies, Hamburg America Line (often referred to as "HAPAG") and Norddeutscher Lloyd, competed in Germany. The First and Second World Wars dealt much damage to the two companies, both forced to renounce their ships to the winning side in both wars. The two merged to form Hapag-Lloyd in 1970.

The ocean liner industry in France also consisted of two rival companies: the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (commonly known as "Transat" or "French Line") and Messageries Maritimes. The CGT operated on the North Atlantic route with well-known liners such as SS Normandie and SS France, while the MM operated in French colonies in Asia and Africa. Decolonization in the second half of the 20th century led to a sharp decline in profit for the MM, and it merged with the CGT in 1975 to form the Compagnie Générale Maritime.[102]

Other nations

In the United States, the United States Lines tried to impose itself on the international scene but failed to compete with European companies. In Italy, the Italian Line was founded in 1932 as a result of a merger of three companies. It was known for operating liners such as SS Rex and SS Andrea Doria.[103] The Japanese established Nippon Yusen, also known as NYK Lines, which ran trans-Pacific liners such as the Hikawa Maru and the Asama Maru.

Routes

North Atlantic

The most important of all routes taken by ocean liners was the North Atlantic route. It accounted for a large part of the clientele, who traveled between ports of Liverpool, Southampton, Hamburg, Le Havre, Cherbourg, Cobh, and New York City. The profitability of this route came from migration to the United States. The need for speed influenced the construction of liners for this route, and the Blue Riband was awarded to the liner with the highest speed.[16] The route was not without danger, as storm and icebergs are common in the North Atlantic. Many shipwrecks occurred on this route, among them that of RMS Titanic, the details of which have been recounted in numerous books, films and documentaries.[104] This route was the preferred route for major shipping companies and was the scene of fierce competition between them.[105]

South Atlantic

_par_Kenneth_Shoesmith.jpg)

The South Atlantic was the route frequented by liners bound for South America, Africa, and sometimes Oceania. The White Star Line had some of its ships, such as the Suevic, on the Liverpool-Cape Town-Sydney route.[106] There was no competition in the South Atlantic as there was in the North Atlantic. There were fewer shipwrecks.[107] The Hamburg Süd operated on this route. Among its ship was the famed SS Cap Arcona.[108]

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea was frequented by many ocean liners. Many companies benefited from migration from Italy and the Balkans to the United States. Cunard's RMS Carpathia served on the Gibraltar-Genoa-Trieste route.[109] Similarly, Italian liners crossed the Mediterranean Sea before entering the North Atlantic Ocean.[110] The opening of the Suez Canal made the Mediterranean a possible route to Asia.[111]

Indian Ocean and the Far East

Colonization made Asia particularly attractive to shipping companies. Many government officials must travel there from time to time. As early as the 1840s, the P&O organized trips to Calcutta via the Suez Isthmus, as the canal had not yet been built.[112] The time it took to travel on this route to India, Southeast Asia, and Japan was long, with many stopovers.[113] The Messageries Maritimes operated on this route, notably in the 1930s, with its motor ships.[114] Similarly, the La Marseillaise, put into service in 1949, was one of the flagships of its fleet. Decolonization caused the loss in the profitability of these ships.[115]

Other

National symbol

The construction of some ocean liners was a result of nationalism. The revival of power of the German navy stemmed from the clear affirmation of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany to see his country become a sea power. Thus, the SS Deutschland of 1900 had the honor to bear the name of its mother country, an honor which she lost after ten years of a disappointing career.[37] RMS Lusitania and RMS Mauretania of 1907 were built with the help of the British government with the desire that the United Kingdom would regain its prestige as a sea power.[39] SS United States of 1952 was the result of a desire by the United States government to possess a large and fast ship that is convertible into a troop transport.[72] SS Rex and SS Conte di Savoia of 1932 were constructed at the demands of Benito Mussolini.[116] Finally, the construction SS France of 1961 was a result of Charles de Gaulle's desire to build on French national pride and was financed by the French government.[117][118]

Some liners did gain great popularity. Mauretania and Olympic had many admirers during their careers, and their retirement and scrapping caused certain sadness. The same was true of Île de France, whose scrapping aroused strong emotion from her admirers.[119] Similarly, Queen Mary was very popular with the British people.[120]

Maritime disasters and incidents

Some ocean liners are known today because of their sinking with great loss of lives. In 1873, RMS Atlantic struck an underwater rock and sank off the coast of Nova Scotia, Canada, killing at least 535 people.[42] In 1912, the sinking of the RMS Titanic, which took approximately 1,500 lives, highlighted the overconfidence of the shipping companies in their ships, such as the failure to put enough lifeboats on board. Safety measures at sea were reexamined following the incident.[105] Two years later, in 1914, RMS Empress of Ireland sank in the Saint Lawrence River after colliding with another ship. 1,012 people died.[121]

Among the other sinkings are the torpedo sinking of the RMS Lusitania in 1915, which resulted in the loss of 1,198 lives and provoked an international outcry, the naval mine sinking of the HMHS Britannic in 1916, and that of MS Georges Philippar, which caught fire and sank in the Gulf of Aden in 1932, killing 54 people.[122] In 1956, the sinking of SS Andrea Doria, with the loss of 46 lives, after a collision with MS Stockholm made the headline.

In 1985, MS Achille Lauro was hijacked off the coast of Egypt by members of the Palestinian Liberation Front, resulting the death of one of the hostages being held by the hijackers. In 1994, she caught fire and sank off the coast of Somalia.[123][124]

In popular culture

Literature

Ocean liners have a strong impact on popular culture, whether during their golden age or afterwards. In 1867, Jules Verne recounted his experience aboard SS Great Eastern in his novel A Floating City. In 1898, writer Morgan Robertson wrote the short novel Futility, or the Wreck of the Titan, which features a British ocean liner Titan that hits an iceberg and sinks in the North Atlantic with great loss of lives. The similarities between the plot of the novel and the sinking of the RMS Titanic 14 years later led to the assertion of conspiracy theories regarding Titanic.[125]

Films

Ocean liners were often a setting of a love story in films, such as the 1939's Love Affair[126][127] Liners were also used as a setting of disaster films. The 1960 film The Last Voyage was filmed on board the Íle de France, which was used as a floating prop and was scuttled for the occasion.[128] The 1972 film The Poseidon Adventure has become a classic of the genre and has spawned many remakes.[129]

The sinking of Titanic also attracted attention of filmmakers. Nearly fifteen films were made to depict it, with James Cameron's 1997 film being the most commercially successful.[130]

See also

References

Citations

- http://www.abc.net.au/local/stories/2015/07/01/4264798.htm Chris Frame – How the Ocean Liner changed the world. ABC National.

- Craig, Robin (1980). Steam Tramps and Cargo Liners 1850–1950. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 0-11-290315-0.

- http://chriscunard.com/history-fleet/translantic-liner/ Ocean Liner vs. Cruise Ship. Chris Frame's Cunard Page.

- Pickford, Nigel (1999). Lost Treasure Ships of the Twentieth Century. Washington, D.C: National Geographic. ISBN 0-7922-7472-5.

- Norris, Gregory J. (December 1981). "Evolution of cruising". Cruise Travel. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Goossens, Reuben (2012). "T/n Michelangelo and Raffaello". ssMaritime.com. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Ferulli 2004, p. 11

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 14

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 12

- Piouffre 2009, p. 10

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 13

- Le Goff 1998, p. 8

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 16

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 19

- Le Goff 1998, p. 9

- Piouffre 2009, p. 100

- Rolt, L.T.C., "Victorian Engineering", 1970, Allen Lane The Penguin Press, ISBN 0-7139-0104-7

- Piouffre 2009, p. 13

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 21

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 25

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 20

- "Ship History". The Cunarders. Archived from the original on 2016-04-04. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- Le Goff 1998, p. 11

- Le Goff 1998, p. 12

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 27

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 29

- Le Goff 1998, p. 16

- L'incendie de L'Austria

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 47

- Le Goff 1998, p. 22

- "THE WHITE STAR LINE". The Red Duster. Archived from the original on 2010-08-19.

- "Umbria". Chris' Cunard Page. Archived from the original on 2010-04-06. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- "SS Ophir". Clydemaritime.

- Le Goff 1998, p. 23

- Ferulli 2004, p. 124

- Piouffre 2009, p. 26

- Le Goff 1998, p. 25

- William B. Saphire, « The White Star Line and the International Mercantile Marine Company » Archived 2008-01-28 at the Wayback Machine, Titanic Historical Society. Accessed 11 July 2010

- Le Goff 1998, p. 33

- Piouffre 2009, p. 16

- Le Goff 1998, p. 37

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 54

- Le Goff 1998, p. 47

- Le Goff 1998, p. 52

- Le Goff 1998, p. 61

- Chirnside 2004, p. 223

- Le Goff 1998, p. 39

- Le Goff 1998, p. 55

- Ferulli 2004, p. 120

- Le Goff 1998, p. 50

- Layton, J. Kent (2009). "H.M.H.S. Britannic". Atlantic Liners. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- « Kronprinz Wilhelm » Archived 2012-09-18 at the Wayback Machine, The Great Ocean Liners. Accessed 12 July 2010

- Le Goff 1998, p. 34

- Le Goff 1998, p. 58

- Le Goff 1998, p. 65

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 63

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 69

- Le Goff 1998, p. 84

- Chirnside 2004, p. 111

- Chirnside 2004, p. 117

- Chirnside 2004, p. 122

- Le Goff 1998, p. 93

- Le Goff 1998, p. 100

- Le Goff 1998, p. 70

- Piouffre 2009, p. 42

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 86

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 87

- Le Goff 1998, p. 69

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 83

- Newman, Jeff (2012). "Empress of Britain (II)". Great Ships. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- Le Goff 1998, p. 73

- Le Goff 1998, p. 109

- Le Goff 1998, p. 112

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 93

- Ljungström, Henrik. "Queen Elizabeth 2: 1969 – Present Day". The Great Ocean Liners. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- "Introduction to the SS Uganda". SS Uganda Trust. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- "Visit Bristol's attraction – Brunel's ss Great Britain". ssgreatbritain.org. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- "DOULOS PHOS TO BECOME HOTEL (p.5)" (PDF). The Porthole. New York, NY: World Ship Society, Port of New York. November 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- Tham, E-lyn (February 16, 2016). "All Aboard! Luxurious Ship-Hotel Set to Open in Bintan". Tripzilla.com. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- "The history of the SS Rotterdam". Steamship Rotterdam Foundation. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- Morris, Hugh (January 13, 2016). "'Forlorn' QE2 is not coming home from Dubai, campaigners concede". Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- MS Marco Polo, Cruise and Maritime Voyages

- "CMV to replace Discovery from the UK". travelmole.com. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- « The Largest Passenger Ships in the World » Archived 2017-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, The Great Ocean Liners. Accessed 12 July 2010

- « The Evolution of Size » Archived 2012-12-29 at the Wayback Machine, The Great Ocean Liners. Accessed 2 July 2010

- « Queen Elizabeth » Archived 2010-08-26 at the Wayback Machine, The Great Ocean Liners. Accessed 12 July 2010

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 46

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 26

- Le Goff 1998, p. 30

- Chirnside 2004, p. 8

- Shifrin, Malcolm (2015). "Chapter 23: The Turkish bath at sea". Victorian Turkish Baths. Historic England. ISBN 978-1-84802-230-0.

- Le Goff 1998, p. 59

- Chirnside 2004, p. 13

- Ferulli 2004, pp. 86–87

- Ferulli 2004, p. 89

- Ferulli 2004, p. 85

- (in French) « Queen Mary 2 » Archived 2010-01-07 at the Wayback Machine, Musée national de la Marine. Accessed 12 July 2010

- Ferulli 2004, p. 84

- Ferulli 2004, pp. 90–93

- Ferulli 2004, pp. 64–65

- Ferulli 2004, pp. 78–79

- Ferulli 2004, p. 63

- Ferulli 2004, pp. 72–73

- Piouffre 2009, p. 101

- Piouffre 2009, p. 112

- « Suevic » Archived 2009-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, The Great Ocean Liners. Accessed 13 July 2010

- Piouffre 2009, p. 164

- « Cap Arcona » Archived 2014-07-12 at the Wayback Machine, The Great Ocean Liners. Accessed 13 July 2010

- « Carpathia » Archived 2016-12-13 at the Wayback Machine, The Great Oceans Liners. Accessed July 13, 2010

- Le Goff 1998, p. 63

- Piouffre 2009, p. 51

- Piouffre 2009, p. 203

- Piouffre 2009, p. 211

- Le Goff 1998, p. 76

- Le Goff 1998, p. 105

- Le Goff 1998, p. 81

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 97

- Offrey, Charles; 303 Arts, recherces et créations:SS Normandie/SS France/SS Norway: France, the Last French Passenger Liner; p. 45

- Le Goff 1998, pp. 64–65

- Le Goff 1998, p. 115

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 55

- Le Goff 1998, p. 77

- Le Goff 1998, p. 102

- Mars & Jubelin 2001, p. 107

- Le Goff 1998, p. 44

- Server 1998, p. 71

- Server 1998, p. 75

- Server 1998, p. 78

- (in French) « L'aventure du Poséidon » (1972), IMDb. Accessed 14 July 2010

- Server 1998, p. 76

Bibliography

- Rémy, Max; Le Boutilly, Laurent (2016). Les "Provinces" Transatlantiques 1882–1927 (in French). Éditions Minimonde76. ISBN 9782954181820.

- Brouard, Jean-Yves (1998). Paquebots de chez nous (in French). MDM. ISBN 9782909313535.

- Chirnside, Mark (2004). The Olympic Class Ships : Olympic, Titanic, Britannic. Tempus. ISBN 9780752428680.

- Ferulli, Corrado (2004). Au cœur des bateaux de légende (in French). Hachette Collections. ISBN 9782846343503.

- Le Goff, Olivier (1998). Les Plus Beaux Paquebots du Monde (in French). Solar. ISBN 9782263027994.

- Mars, Christian; Jubelin, Frank (2001). Paquebots (in French). Sélection du Reader's Digest. ISBN 9782709812863.

- Piouffre, Gérard (2009). L'Âge d'or des voyages en paquebot (in French). Éditions du Chêne. ISBN 9782812300028.

- Scull, Theodore W. (1998). Ocean Liner Odyssey, 1958-1969. London: Carmania Press. ISBN 0951865692.

- Scull, Theodore W. (2007). Ocean Liner Twilight: Steaming to Adventure, 1968-1979. Windsor: Overview Press. ISBN 9780954720636.

- Scull, Theodore W. (2017). Ocean Liner Sunset. Windsor: Overview Press. ISBN 9780954702687.

- Server, Lee (1998). L'Âge d'or des paquebots (in French). MLP. ISBN 2-7434-1050-7.

Further reading

- Russell, Mark A. "Steamship nationalism: Transatlantic passenger liners as symbols of the German Empire." International Journal of Maritime History 28.2 (2016): 313–334. Abstract.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ocean liners. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ocean liners. |