Occupy Wall Street

Occupy Wall Street (OWS) was a protest movement against economic inequality that began in Zuccotti Park, located in New York City's Wall Street financial district, in September 2011.[7] It gave rise to the wider Occupy movement in the United States and other countries.

| Occupy Wall Street | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Occupy movement | |

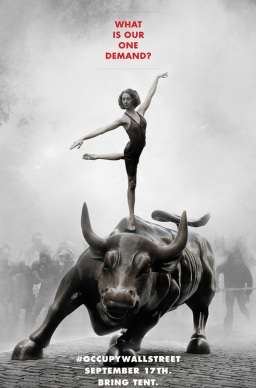

Adbusters poster advertising the original protest | |

| Date | September 17, 2011 |

| Location | New York City 40°42′33″N 74°0′40″W |

| Caused by | Wealth inequality, political corruption,[1] corporate influence of government |

| Methods |

|

| Number | |

Zuccotti Park Other activity in NYC:

| |

The Canadian anti-consumerist and pro-environment group/magazine Adbusters initiated the call for a protest. The main issues raised by Occupy Wall Street were social and economic inequality, greed, corruption and the undue influence of corporations on government—particularly from the financial services sector. The OWS slogan, "We are the 99%", refers to income and wealth inequality in the U.S. between the wealthiest 1% and the rest of the population. To achieve their goals, protesters acted on consensus-based decisions made in general assemblies which emphasized redress through direct action over the petitioning to authorities.[8][nb 1]

The protesters were forced out of Zuccotti Park on November 15, 2011. Protesters then turned their focus to occupying banks, corporate headquarters, board meetings, foreclosed homes, and college and university campuses.

Origins

The original protest was called for by Kalle Lasn and others of Adbusters, a Canadian anti-consumerist publication, who conceived of a September 17 occupation in Lower Manhattan. The first such proposal appeared on the Adbusters website on February 2, 2011, under the title "A Million Man March on Wall Street."[9] Lasn registered the OccupyWallStreet.org web address on June 9.[10] The website has since been taken down. That same month, Adbusters emailed its subscribers saying "America needs its own Tahrir." White said the reception of the idea "snowballed from there".[10][11] In a blog post on July 13, 2011,[12] Adbusters proposed a peaceful occupation of Wall Street to protest corporate influence on democracy, the lack of legal consequences for those who brought about the global crisis of monetary insolvency, and an increasing disparity in wealth.[11] The protest was promoted with an image featuring a dancer atop Wall Street's iconic Charging Bull statue.[13][14][15]

Meanwhile, several similar proposals were being explored by independent groups, as reported by journalist Nathan Schneider in his book Thank You, Anarchy: Notes from the Occupy Apocalypse.[16] Thousands of people organized by a group of labor unions marched on Wall Street 12; the online collective Anonymous attempted an occupation on June 14; activists planned an indefinite occupation of Freedom Plaza in Washington, D.C., which eventually became known as Occupy Washington, D.C.; in New York City a group of protestors met for several months to plan an occupation which was originally to be stationed at Chase Plaza, with Zucotti Park as "Plan B".

On August 1, 2011, almost a month prior to the major media event, a group of artists were arrested after a series of days protesting nude as an art performance on Wall Street.[17] This event may have inspired or triggered the major event to follow. This was a protest by the 49 participants on American Institutions and was titled "Ocularpation: Wall Street" by artist Zefrey Throwell.[18]

Then in an unrelated incident, a group called New Yorkers Against Budget Cuts (NYAB) was formed, which promoted a "sleep in" in lower Manhattan called "Bloombergville", in July 2011, preceding OWS, and provided a number of activists to begin organizing.[19][20] Activist, anarchist and anthropologist David Graeber and several of his associates attended the NYAB general assembly but, disappointed that the event was intended to be a precursor to marching on Wall Street with predetermined demands, Graeber and his small group created their own general assembly, which eventually developed into the New York General Assembly. The group began holding weekly meetings to work out issues and the movement's direction, such as whether or not to have a set of demands, forming working groups and whether or not to have leaders.[10][21][22][nb 2] The Internet group Anonymous created a video encouraging its supporters to take part in the protests.[23] The U.S. Day of Rage, a group that organized to protest "corporate influence [that] corrupts our political parties, our elections, and the institutions of government", also joined the movement.[24][25] The protest itself began on September 17; a Facebook page for the demonstrations began two days later on September 19 featuring a YouTube video of earlier events. By mid-October, Facebook listed 125 Occupy-related pages.[26]

The original location for the protest was One Chase Manhattan Plaza, with Bowling Green Park (the site of the "Charging Bull") and Zuccotti Park as alternate choices. Police discovered this before the protest began and fenced off two locations; but they left Zuccotti Park, the group's third choice, open. Since the park was private property, police could not legally force protesters to leave without being requested to do so by the property owner.[27][28] At a press conference held the same day the protests began, New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg explained, "people have a right to protest, and if they want to protest, we'll be happy to make sure they have locations to do it."[25]

Because of its connection to the financial system, lower Manhattan has seen many riots and protests since the 1800s,[29] and OWS has been compared to other historical protests in the United States.[30] Commentators have put OWS within the political tradition of other movements that made themselves known by occupation of public spaces, such as Coxey's Army in 1894, the Bonus Marchers in 1932, and the May Day protesters in 1971.[31][32]

More recent prototypes for OWS include the British student protests of 2010, 2009-2010 Iranian election protests, the Arab Spring protests,[33] and, more closely related, protests in Chile, Greece, Spain and India. These antecedents have in common with OWS a reliance on social media and electronic messaging,[34][35] as well as the belief that financial institutions, corporations, and the political elite have been malfeasant in their behavior toward youth and the middle class.[36][37] Occupy Wall Street, in turn, gave rise to the Occupy movement in the United States.[38][39][40] David Graeber has argued that the Occupy movement, in its anti-hierarchical and anti-authoritarian consensus-based politics, its refusal to accept the legitimacy of the existing legal and political order, and its embrace of prefigurative politics, has roots in an anarchist political tradition.[41] Sociologist Dana Williams has likewise argued that "the most immediate inspiration for Occupy is anarchism", and the LA Times has identified the "controversial, anarchist-inspired organizational style" as one of the hallmarks of OWS.[42][43]

Background

"We are the 99%"

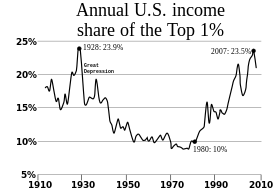

The Occupy protesters' slogan "We are the 99%" referred to the protester's perceptions of, and attitudes regarding, income disparity in the US and economic inequality in general, which were main issues for OWS. It derives from a "We the 99%" flyer calling for OWS's second General Assembly in August 2011. The variation "We are the 99%" originated from a Tumblr page of the same name.[44][45] Huffington Post reporter Paul Taylor said the slogan was "arguably the most successful slogan since 'Hell no, we won't go!'" of the Vietnam War era, and that the majority of Democrats, independents and Republicans saw the income gap as causing social friction.[44] The slogan was boosted by statistics which were confirmed by a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report released in October 2011.[46]

Income and wealth inequality

Income inequality and Wealth Inequality were focal points of the Occupy Wall Street protests.[52][53][54] This focus by the movement was studied by Arindajit Dube and Ethan Kaplan of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who noted that "inequality in the U.S. has risen dramatically over the past 40 years. So it is not too surprising to witness the rise of a social movement focused on redistribution ... Greater inequality may reflect as well as exacerbate factors that make it relatively more difficult for lower-income individuals to mobilize on behalf of their interests ... Yet, even the economic crisis of 2007 did not initially produce a left social movement ... Only after it became increasingly clear that the political process was unable to enact serious reforms to address the causes or consequences of the economic crisis did we see the emergence of the OWS movement ... Overall, a focus on the 1 percent concentrates attention on the aspect of inequality most clearly tied to the distribution of income between labor and capital ... We think OWS has already begun to influence the public policy making process."[55]

An article on the same subject published in Salon Magazine by Natasha Leonard noted "Occupy has been central to driving media stories about income inequality in America. Late last week, Radio Dispatch's John Knefel compiled a report for media watchdog Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), which illustrates Occupy's success: Media focus on the movement in the past half year, according to the report, has been almost directly proportional to the attention paid to income inequality and corporate greed by mainstream outlets. During peak media coverage of the movement last October, mentions of the term "income inequality" increased "fourfold"... tokens of Occupy rhetoric — most notably the idea of a "99 percent" against a "1 percent" — has seeped into everyday cultural parlance."[56] As income inequality remained on people's minds, Republican Presidential Candidate Mitt Romney said such a focus was about envy and class warfare.[57]

Goals

OWS's goals included a reduction in the influence of corporations on politics,[59] more balanced distribution of income,[59] more and better jobs,[59] bank reform[40] (especially to curtail speculative trading by banks[60]), forgiveness of student loan debt[59][61] or other relief for indebted students,[62][63] and alleviation of the foreclosure situation.[64] Some media labeled the protests "anti-capitalist",[65] while others disputed the relevance of this label.[66] Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times noted "while alarmists seem to think that the movement is a 'mob' trying to overthrow capitalism, one can make a case that, on the contrary, it highlights the need to restore basic capitalist principles like accountability".[67] Rolling Stone writer Matt Taibbi asserted, "These people aren't protesting money. They're not protesting banking. They're protesting corruption on Wall Street."[68] In contradiction to such views, academic Slavoj Zizek wrote, "capitalism is now clearly re-emerging as the name of the problem,"[69] and Forbes columnist Heather Struck wrote, "In downtown New York, where protests fomented, capitalism is held accountable for the dire conditions that a majority of Americans face amid high unemployment and a credit collapse that has ruined the housing market and tightened lending among banks."[70]

Some protestors favored a fairly concrete set of national policy proposals.[71][72] One OWS group that favored specific demands created a document entitled the 99 Percent Declaration,[73] but this was regarded as an attempt to "co-opt" the "Occupy" name,[74] and the document and group were rejected by the General Assemblies of Occupy Wall Street and Occupy Philadelphia.[74] However others, such as those who issued the Liberty Square Blueprint, are opposed to setting demands, saying they would limit the movement by implying conditions and limiting the duration of the movement.[75] David Graeber, an OWS participant, also criticized the idea that the movement must have clearly defined demands, arguing that it would be a counterproductive legitimization of the power structures the movement sought to challenge.[76] In a similar vein, scholar and activist Judith Butler challenged the assertion that OWS should make concrete demands: "So what are the demands that all these people are making? Either they say there are no demands and that leaves your critics confused. Or they say that demands for social equality, that demands for economic justice are impossible demands and impossible demands are just not practical. But we disagree. If hope is an impossible demand then we demand the impossible."[77] Regardless, activists favored a new system that fulfills what is perceived as the original promise of democracy to bring power to all the people.[78]

During the occupation in Liberty Square, a declaration was issued with a list of grievances. The declaration stated that the "grievances are not all-inclusive".[79][80]

Protester demographics

Early on the protesters were mostly young.[81][82] As the protest grew, older protesters also became involved.[83] The average age of the protesters was 33, with people in their 20s balanced by people in their 40s.[84] Various religious faiths have been represented at the protest including Muslims, Jews, and Christians.[85] Rabbi Chaim Gruber,[86] however, is reportedly the only clergy member to have actually camped at Zuccotti Park.[87][88][89] The Associated Press reported in October that there was "diversity of age, gender and race" at the protest.[83] A study based on survey responses at OccupyWallSt.org reported that the protesters were 81.2% White, 6.8% Hispanic, 2.8% Asian, 1.6% Black, and 7.6% identifying as "other".[90][91]

According to a survey of occupywallst.org website visitors[92] by the Baruch College School of Public Affairs published on October 19, of 1,619 web respondents, one-third were older than 35, half were employed full-time, 13% were unemployed and 13% earned over $75,000. When given the option of identifying themselves as Democratic, Republican or Independent/Other 27.3% of the respondents called themselves Democrats, 2.4% called themselves Republicans, while the rest, 70%, called themselves independents.[93] A study released by City University of New York found that over a third of protesters had incomes over $100,000, 76% had bachelor's degrees, and 39% had graduate degrees. While a large percent of them were employed, they largely reported they were "unconstrained by highly demanding family or work commitments". The study also found that they disproportionally represented upper-class, highly educated white males.[94][95] A survey of 301 respondents by a Fordham University political science professor identified the protester's political affiliations as 25% Democratic, 2% Republican, 11% Socialist, 11% Green Party, 0% Tea Party, and 12% "Other"; meanwhile, 39% of the respondents said they did not identify with any political party.[96] Ideologically the Fordham survey found 39% self-identifying as extremely liberal, 33% as Liberal, 8% as slightly liberal, 15% as moderate/"middle of the road", 2% as slightly conservative, 3% as conservative, and 1% as extremely conservative.[97]

Main organization

The assembly was the main OWS decision-making body and used a modified consensus process, where participants attempted to reach consensus and then dropped to a 9/10 vote if consensus was not reached.

Assembly meetings involved OWS working groups and affinity groups, and were open to the public for both attendance and speaking.[98] The meetings lacked formal leadership. Participants commented upon committee proposals using a process called a "stack", which is a queue of speakers that anyone can join. New York used a progressive stack, in which people from marginalized groups are sometimes allowed to speak before people from dominant groups. Facilitators and "stack-keepers" urge speakers to "step forward, or step back" based on which group they belong to, meaning that women and minorities often moved to the front of the line, while white men often had to wait for a turn to speak.[99][100] In addition to the over 70 working groups,[101] the organizational structure also includes "spokes councils", at which every working group can participate.[102]

Funding

During the initial weeks of the park encampment it was reported that most of OWS funding was coming from donors with incomes in the $50,000 to $100,000 range, and the median donation was $22.[84] According to finance group member Pete Dutro, OWS had accumulated over $700,000.[103] The largest single donor to the movement was former New York Mercantile Exchange vice chairman Robert Halper, who was noted by media as having also given the maximum allowable campaign contribution to Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney.[104] During the period that protesters were encamped in the park the funds were being used to purchase food and other necessities and to bail out fellow protesters. With the closure of the park to overnight camping on November 15, members of the OWS finance committee stated they would initiate a process to streamline the movement and re-evaluate their budget and eliminate or merge some of the "working groups" they no longer needed on a day-to-day basis.[105][106]

Met with increasing costs and significant overhead expenses in order to sustain the movement, an internal audit from the fiscal management team known as the "accounting working group" revealed on March 2, 2012, that only $44,000 of the several hundred thousand dollars raised still remained available. The report warned that if current revenues and expenses were maintained at current levels, then funds would run out in three weeks.[107][108] Some of the movement's biggest costs include ground-level activities such as food kitchens, street medics, bus tickets, subway passes, and printing expenses.[109][110]

In late February 2012 it was reported that a group of business leaders including Ben Cohen, Jerry Greenfield, Danny Goldberg, Norman Lear, and Terri Gardner[111] created a new working group, the Movement Resource Group, and with it have pledged $300,000 with plans to add $1,500,000 more.[112][113] The money would be made available in the form of grants of up to $25,000 for eligible recipients.

The People's Library

The People's Library at Occupy Wall Street was started a few days after the protest when a pile of books was left in a cardboard box at Zuccotti Park. The books were passed around and organized, and as time passed, it received additional books and resources from readers, private citizens, authors and corporations.[114] As of November 2011 the library had 5,554 books cataloged in LibraryThing and its collection was described as including some rare or unique articles of historical interest.[115] According to American Libraries, the library's collection had "thousands of circulating volumes", which included "holy books of every faith, books reflecting the entire political spectrum, and works for all ages on a huge range of topics."[114]

Following the example of the OWS People's Library, protesters throughout North America and Europe formed sister libraries at their encampments.[116]

Zuccotti Park encampment

Prior to being closed to overnight use and during the occupation of the space, somewhere between 100 and 200 people slept in Zuccotti Park. Initially tents were not allowed and protesters slept in sleeping bags or under blankets.[117] Meal service started at a total cost of about $1,000 per day. While some visitors ate at nearby restaurants, according to the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post many businesses surrounding the park were adversely affected.[118][119][120] Contribution boxes collected about $5,000 a day, and supplies came in from around the country.[118] Eric Smith, a local chef who was laid off at the Sheraton in Midtown, said that he was running a five-star restaurant in the park.[121] In late October, kitchen volunteers complained about working 18-hour days to feed people who were not part of the movement and served only brown rice, simple sandwiches, and potato chips for three days.[122]

Many protesters used the bathrooms of nearby business establishments. Some supporters donated use of their bathrooms for showers and the sanitary needs of protesters.[123]

New York City requires a permit to use "amplified sound", including electric bullhorns. Since Occupy Wall Street did not have a permit, the protesters created the "human microphone" in which a speaker pauses while the nearby members of the audience repeat the phrase in unison. The effect has been called "comic or exhilarating—often all at once." Some feel this provided a further unifying effect for the crowd.[124][117]

During the weeks that overnight use of the park was allowed, a separate area was set aside for an information area which contained laptop computers and several wireless routers.[125][126] The items were powered with gas generators until the New York City Fire Department removed them on October 28, saying they were a fire hazard.[127] Protesters then used bicycles rigged with an electricity-generating apparatus to charge batteries to power the protesters' laptops and other electronics.[128][129] According to the Columbia Journalism Review's New Frontier Database, the media team, while unofficial, ran websites like Occupytogether.org, video livestream, a "steady flow of updates on Twitter, and Tumblr" as well as Skype sessions with other demonstrators.[130]

On October 6, Brookfield Office Properties, which owns Zuccotti Park, issued a statement saying: "Sanitation is a growing concern ... Normally the park is cleaned and inspected every weeknight [but] because the protesters refuse to cooperate ... the park has not been cleaned since Friday, September 16 and as a result, sanitary conditions have reached unacceptable levels."[131][132]

On October 13, New York City's mayor Bloomberg and Brookfield announced that the park must be vacated for cleaning the following morning at 7 am.[133] However, protesters vowed to "defend the occupation" after police said they would not allow them to return with sleeping bags and other gear following the cleaning, and many protesters spent the night sweeping and mopping the park.[134][135] The next morning the property owner postponed its cleaning effort.[134] Having prepared for a confrontation with the authorities to prevent the cleaning effort from proceeding, some protesters clashed with police in riot gear outside City Hall after it was canceled.[133] MTV followed two protesters for their series True Life; one of whom, Bryan, was on the sanitation crew. Filming took place during the time when the cleanup happened.[136]

On October 20, residents at a community board meeting complained about inadequate sanitation, verbal taunts and harassment by protesters, noise, and related issues. One resident angrily complained that the protesters "[a]re defecating on our doorsteps"; board member Tricia Joyce said, "They have to have some parameters. That doesn't mean the protests have to stop. I'm hoping we can strike a balance on parameters because this could be a long term stay."[137]

Shortly after midnight on November 15, 2011, the New York City Police Department gave protesters notice from the park's owner (Brookfield Office Properties) to leave Zuccotti Park due to its purportedly unsanitary and hazardous conditions. The notice stated that they could return without sleeping bags, tarps or tents.[138][139] About an hour later, police in riot gear began removing protesters from the park, arresting some 200 people in the process, including a number of journalists.

On December 31, 2011, protesters started to re-occupy the park. At one point, protesters started to push police barricades into the streets. Police quickly put the barricades back up. Occupiers then started to take down barricades from all sides of the park and stored them in a pile in the middle of Zuccotti Park.[140] Police called in reinforcements as more activists entered the park. Police tried to enter the park but were pushed back by protesters. There were reports of pepper-spray being used by the police. At about 12:40 am, after the group celebrated New Years in the park, they exited the park and marched down Broadway. Police in riot gear started to clear out the park around 1:30 am. Sixty-eight people were arrested in connection with the event, including one accused of stabbing a police officer in the hand with a pair of scissors.[141]

When the Zuccotti Park encampment was closed, some former campers were allowed to sleep in local churches. Since the removal, New York protesters have been divided in their opinion as to the importance of the occupation of a space, with some believing that actual encampment is unnecessary, and even a burden.[142] Since the closure of the Zuccotti Park encampment, the movement has turned its focus on occupying banks, corporate headquarters, board meetings, foreclosed homes, college and university campuses, and Wall Street itself. Since its inception, the Occupy Wall Street protests in New York City have cost the city an estimated $17 million in overtime fees to provide policing of protests and encampment inside Zuccotti Park.[143][144][145]

On March 17, 2012, Occupy Wall Street demonstrators attempted to mark the movement's six-month anniversary by reoccupying Zuccotti Park. Protesters were soon cleared away by police, who made over 70 arrests. Veteran protesters said the force used by police was the most violent they had witnessed and a Guardian reporter witnessed a protester being slammed into a glass door by a police officer.[146][147] On March 24, hundreds of OWS protesters marched from Zuccotti Park to Union Square in a demonstration against police violence.[148]

On September 17, 2012, protesters returned to Zuccotti Park to mark the one-year anniversary of the beginning of the occupation. Protesters blocked access to the New York Stock Exchange as well as other intersections in the area. This, along with several violations of Zuccotti Park rules, led police to surround groups of protesters, at times pulling protesters from the crowds to be arrested for blocking pedestrian traffic. A police lieutenant instructed reporters not to take pictures. The New York Times reported that two officers shoved city councilman Jumaane D. Williams off a bench with batons after he refused two orders to move. A spokesman for Williams later stated that he had been pushed by police while trying to explain his reason for being in the park, but was not arrested or injured. There were 185 arrests across the city.[149][150][151][152]

Occupy media

Occupy Wall Street activists disseminated their movement updates through variety of mediums, including social media, print magazines, newspapers, film, radio and live stream. Like much of Occupy, many of these alternative media projects were collectively managed, while autonomous from the decision making bodies of Occupy Wall Street.[153][154]

Occupied Media Pamphlet Series

Occupied Media Pamphlet Series, published by Zuccotti Park Press was co-founded by Open Magazine Pamphlet Series and Adelante Alliance. A published series of 5 mini-books available for purchase, by different renowned academics and activists offering their perspectives and visions for the Occupy movement. Occupy, the first book in the series, by Noam Chomsky was launched on May 1, 2012.[155]

Chomsky, Noam (2012). Occupy: Reflections on Class War, Rebellion and Solidarity. Occupied Media Pamphlet Series. Zuccotti Park Press. ISBN 978-1884519017.

Sitrin, Marina; Azzellini, Dario (2012). Occupying Language: The Secret Rendezvous with History and the Present. Zuccotti Park Press. ISBN 978-1884519093.

Abu-Jamal, Mumia; Walker, Alice (2012). Message to the Movement. Zuccotti Park Press. ISBN 978-1884519079.

Leonard, Stuart (2012). Taking Brooklyn Bridge. Zuccotti Park Press. ISBN 978-1884519055.

Gottesdiener, Laura (2013). A Dream Foreclosed: Black America and the Fight for a Place to Call Home. Zuccotti Park Press. ISBN 978-1884519215.

Occupied Wall Street Journal

The Occupied Wall Street Journal (OWSJ) was a free newspaper founded in October 2011 by independent journalists Arun Gupta, Jed Brandt and Michael Levitin.[156] Over $75,000 was raised through Kickstarter to fund the distribution and printing of the newspaper. Indypendent Media provided the printing facilities.[157][158] It featured the voices of prominent activist/academics as well as lesser known members of the 99% in four page color issues.[159] The first issue had a total print run of 70,000 copies, along with an unspecified number in Spanish.[160] Its last article appeared in February 2012.

OWSJ was not an official organ of the Occupy movement, but it did publish official statements of the Occupy movement, for example, in its first issue, it disseminated The Declaration of Occupy Wall Street and meeting minutes from the General Assembly decision-making bodies.[159][160][161]

Occuprint

The Occuprint collective, founded by Jesse Goldstein and Josh MacPhee, formed through the curation of the fourth and special edition of The Occupied Wall Street Journal (OWSJ), featuring 21 posters and graphics highlighting Occupy art.[162][163] Afterwards, it continued to collect and publish images under the Creative Commons for non commercial use license, to spread the artwork throughout the movement. In addition to sending out posters across the different Occupy encampments, Occuprint collaborated with the OWS Screen Printing Guild to make buttons and silk screen clothing free of cost.[164][165]

Jesse Goldstein, Dave Loewenstein, Alexandra Clotfelter and Marshall Weber of Booklyn Artist Alliance selected 31 hand silk-screened prints out of hundreds of submissions, with the goal that limited editions of them end up in museums, libraries, archive centers and universities, preserving and sharing Occupy's legacy. Tens of thousands more copies were distributed for free across the country to different Occupy groups.[166][167] In October 2013, the Museum of Modern Art confirmed it acquired the originals of the Occuprint portfolio.[168]

As part of the Occupy Sandy disaster response to Hurricane Sandy, Occuprint created a 12-page resource pamphlet on how to survive and seek help, after determining that the FEMA booklets were incomplete. 6,000 copies were made in first print run, with a total circulation of 12,000.[169][170]

Occupy! Gazette

The Occupy! Gazette was founded by editors Astra Taylor, Keith Gessen of N+1 and Sarah Leonard of Dissent Magazine. It published five issues from October 2011 to September 2012,[171] with a commemorative sixth issue published in May 2014, to support OWS activist Cecily McMillan during the sentencing phase of her trial.[172][173] Each issue ranged from thirty to forty pages and was featured in a different color theme each time.

Articles from Occupy! were later anthologized in a book titled Occupy!: Scenes From Occupied America, published by Verso Books in 2012.[174]

Tidal

Tidal: Occupy Theory, Occupy Strategy magazine was published twice a year, with its first release in December 2011, the fourth and final issue in March 2013. It consisted of long essays, poetry and art within thirty pages. Each issue had a circulation of 12,000 to 50,000.[175]

Security, crime and legal issues

OWS demonstrators complained of thefts of assorted items such as cell phones and laptops; thieves also stole $2,500 of donations that were stored in a makeshift kitchen.[176] In November, a man was arrested for breaking an EMT's leg.[177]

NYPD spokesman Paul Browne said protesters delayed reporting crime until three complaints were made against the same individual.[178] The protesters denied a "three strikes policy", and one protester told the New York Daily News that he had heard police respond to an unspecified complaint by saying, "You need to deal with that yourselves".[179]

After several weeks of occupation, protesters had made enough allegations of rape, sexual assault, and gropings that women-only sleeping tents were set up.[180][181][182][183] Occupy Wall Street organizers released a statement regarding the sexual assaults stating, "As individuals and as a community, we have the responsibility and the opportunity to create an alternative to this culture of violence, We are working for an OWS and a world in which survivors are respected and supported unconditionally ... We are redoubling our efforts to raise awareness about sexual violence. This includes taking preventative measures such as encouraging healthy relationship dynamics and consent practices that can help to limit harm."[184]

It was revealed that an internal Department of Homeland Security report warned that Occupy Wall Street protests were a potential source of violence; the report stated that "mass gatherings associated with public protest movements can have disruptive effects on transportation, commercial, and government services, especially when staged in major metropolitan areas". The DHS keeps a file on the movement and monitors social media for information, according to leaked emails released by WikiLeaks.[185][186]

Government crackdowns

Surveillance

As the movement spread across the United States, the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) began keeping tabs on protesters. A DHS report entitled "SPECIAL COVERAGE: Occupy Wall Street", dated October 2011, observed that "mass gatherings associated with public protest movements can have disruptive effects on transportation, commercial, and government services, especially when staged in major metropolitan areas."[187]

On December 21, 2012, Partnership for Civil Justice obtained and published U.S. government documents[188] revealing that over a dozen local FBI field offices, DHS and other federal agencies monitored Occupy Wall Street, despite labeling it a peaceful movement.[189] The New York Times reported in May 2014 that declassified documents showed extensive surveillance of OWS related groups across the country.[190]

Arrests

Gideon Oliver, who represented Occupy with the National Lawyers Guild in New York, said about 2,000 [protesters] had been arrested just in New York City alone. Most of these arrests in New York and elsewhere, are on charges of disorderly conduct, trespassing, and failure to disperse.[191] Nationally, a little under 8,000 Occupy affiliated arrests have been documented by tallying numbers published in local newspapers.[192]

In a report[193] that followed an eight-month study, researchers at the law schools of NYU and Fordham accuse the NYPD of deploying unnecessarily aggressive force, obstructing press freedoms and making arbitrary and baseless arrests.[194]

Brooklyn Bridge arrests

On October 1, 2011, a large group of protesters set out to walk across the Brooklyn Bridge resulting in 768 arrests, the largest number of arrests in one day at any Occupy event. Some said the police had tricked protesters, allowing them onto the bridge, and even escorting them partway across.[195][196] Jesse A. Myerson, a media coordinator for Occupy Wall Street said, "The cops watched and did nothing, indeed, seemed to guide us onto the roadway."[197] A spokesman for the New York Police Department, Paul Browne, said that protesters were given multiple warnings to stay on the sidewalk and not block the street, and were arrested when they refused.[2] By October 2, all but 20 of the arrestees had been released with citations for disorderly conduct and a criminal court summons.[198] On October 4, a group of protesters who were arrested on the bridge filed a lawsuit against the city, alleging that officers had violated their constitutional rights by luring them into a trap and then arresting them.[199]

In June 2012, a federal judge ruled that the protesters had not received sufficient warning.[200]

Court cases

In May 2012, three cases in a row were thrown out of court, the most recent one for "insufficient summons".[201] In another case, photographer Alexander Arbuckle was charged with blocking traffic for standing in the middle of the street, according to NYPD Officer Elisheba Vera. However, according to Village Voice staff writer Nick Pinto, this account was not corroborated by photographic and video evidence taken by protesters and the NYPD.[202] In yet another case, Sgt. Michael Soldo, the arresting officer, said Jessica Hall was blocking traffic. But under cross-examination Soldo admitted, it was actually the NYPD metal barricades which blocked traffic. This was also corroborated by the NYPD's video documentation.[203]

In 2011, eight men associated with Occupy Wall Street were found guilty of trespassing, having intended to set up a camp on property controlled by Trinity Church. One was also convicted of attempted criminal mischief and attempted criminal possession of burglar's tools for trying to slice a lock on a chain-link fence with bolt cutters, spending a month in prison. The rest were sentenced to community service.[204][205]

One defendant, Michael Premo, charged with assaulting an officer, was found not guilty after the defense presented video evidence which "showed officers charging into the defendant unprovoked", contradicting the sworn testimony of NYPD officers.[206]

A court has ordered that the City pay $360,000 for their actions during the November 15, 2011 raid.[207] That case, Occupy Wall Street v. City of New York, was filed in the US District Court Southern District of New York.[208] Further, the City of New York has since begun settling cases with individual participants. The first of which was most notably represented by students of Hofstra Law School and the Occupy Wall Street Clinic.[209]

Nkrumah Tinsley was indicted on riot offenses and assaulting a police officer during the Zuccotti Park encampment. On May 21, 2013 Tinsley pleaded guilty to felony assault on a police officer, and will be sentenced later 2013.[210]

In April 2014, the final Occupy court case, the Trial of Cecily McMillan began. Cecily McMillan was charged with and convicted of assaulting a police officer and sentenced to 90 days in Rikers Island Penitentiary.[211] McMillan claimed the assault was an accident and a response to what she claimed to be a sexual assault at the hands of said officer.[212] The jury that found her guilty recommended no jail time.[213] She was released after serving 60 days.[214]

Anarchism

Many commentators have stated that the Occupy Wall Street movement has roots in the philosophy of anarchism.[215][216][217][218][219] David Graeber, an early organizer of the movement, is a self-proclaimed anarchist.[220] Graeber, writing for The Guardian, has argued that anarchist principles of direct action, direct democracy and rejection of existing political institutions are the foundations of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Graber associated Occupy with anarchism ideology because of Occupy's refusal to make demands on the existing state.[221] The view was that had Occupy made demands, it would be reiterating the legitimacy of the people who made the demands; refraining from making demands, Occupy refused to legitimize the existing political structure of the United States.[221] Graeber also believes that radical segments of the civil rights movement, the anti-nuclear movement and the global justice movement have been based on the same principles.[222]

As "Occupy" encompassed a range of perspectives, a range of participants viewed it as an anarchist movement and others argued it could not be labeled an anarchist movement.[223] John L. Hammond attributes three core Occupy beliefs and practices – horizontalism, autonomy, and defiance – as also being anarchist values and argued that Occupy's emphasis on the experience of occupation aligns with the principles of libertarian anarchists.[224] Horizontalism, meaning an equal distribution of power, was demonstrated through the creation of a direct democracy that eliminated hierarchy and representative structures.[225] Occupy operated using mutualism and self-organization as its principles. The General Assemblies practiced direct democracy using consensus to the extent of practicality. Outside of the General Assemblies, Occupy protesters organized into decentralized groups. Occupy's practice of horizontal organization rejected the legitimacy of the existing hierarchical political structure in the United States.[223] Some writers have argued that by questioning institutions like the existing state Occupy demonstrated both autonomy and defiance.[226]

Thai Jones, an anarchist writing for the Jewish-American weekly newspaper, The Forward, asserted that the Occupy movement demonstrated that the invigorating potential of anarchist political theory can be a feasible model of governance. According to Jones, contemporary anarchists involved in the Occupy Wall Street movement face the same dilemma as their early predecessors — whether to use violence.[227] Michael Kazin, writing for The New Republic, analyzed the composition of the Occupy Wall Street movement. He argued that Occupy members are different from political activists of the late 19th century and early 20th century counterparts, citing contemporary rejection of violent methods as the main difference.

Kazin described the Occupy Wall Street anarchists as "ultra-egalitarian, radically environmentalist, effortlessly multicultural and scrupulously non-violent", describing them as the "cyber-clever progeny of Henry David Thoreau and Emma Goldman." Social media played a vital role in the Occupy movement and Kazin noted that instead of authoring essays or promoting feminism and free love, the Occupy Wall Street anarchists stream videos and arrange flash mobs.[218]

In November 2011, approximately 100 people participated in Portland's "Anarchist General Assembly" and discussed ways to spread anarchist ideas and how to interact with police. The organizers of the assembly published a flier that read, "This is a call to the anarchist and broader anti-authoritarian community to reconvene in assembly and continue to develop ourselves as members of a larger network here in Portland."[228]

Notable responses

During an October 6 news conference, President Barack Obama said, "I think it expresses the frustrations the American people feel, that we had the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression, huge collateral damage all throughout the country ... and yet you're still seeing some of the same folks who acted irresponsibly trying to fight efforts to crack down on the abusive practices that got us into this in the first place."[229][230]

On October 5, 2011, noted commentator and political satirist Jon Stewart said in his Daily Show broadcast: "If the people who were supposed to fix our financial system had actually done it, the people who have no idea how to solve these problems wouldn't be getting shit for not offering solutions."[231]

Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney said that while there were "bad actors" that needed to be "found and plucked out", he believes that targeting one industry or region of America is a mistake and views encouraging the Occupy Wall Street protests as "dangerous" and inciting "class warfare".[232][233] Romney later expressed sympathy for the movement, saying, "I look at what's happening on Wall Street and my view is, boy, I understand how those people feel."[234]

House Democratic Leader Rep. Nancy Pelosi said she supports the Occupy Wall Street movement.[235] In September, various labor unions, including the Transport Workers Union of America Local 100 and the New York Metro 32BJ Service Employees International Union, pledged their support for demonstrators.[236]

Five days into the protest, political commentator Keith Olbermann, formerly of CurrentTV, vocally criticized mainstream media outlets for failing to cover the initial Wall Street protests and demonstrations adequately.[237][238]

On October 19, 2011, Greenpeace Executive Director Phil Radford spoke on behalf of Greenpeace supporting Occupy Wall Street protesters, stating: "We stand – as individuals and an organization – with Occupiers of all walks of life who peacefully stand up for a just, democratic, green and peaceful future."[239]

The Internet Archive and the Occupy Archive, a project at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, has been collecting material from Occupy sites beyond New York.[240][241]

In November 2011, Public Policy Polling did a national survey which found that 33% of voters supported OWS and 45% opposed it, with 22% not sure. 43% of those polled had a higher opinion of the Tea Party movement than the Occupy movement.[242] In January 2012, a survey was released by Rasmussen Reports, in which 51% of likely voters found protesters to be a public nuisance, while 39% saw it as a valid protest movement representing the people.[243]

Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Chris Hedges, a supporter of the movement, argues that OWS had popular support and "articulated the concerns of the majority of citizens."[244]

American political philosopher Jodi Dean, while critical of the movements focus on autonomy, leaderlessness and horizontality which she argues was self-destructive, says that "Occupy ruptured the lie that 'what is good for Wall Street is good for Main Street'."[245]

Many notable figures joined the occupation, including David Crosby, Kanye West, Russell Simmons, Alec Baldwin, Susan Sarandon, Don King, Noam Chomsky, Jesse Jackson, Cornel West, and Michael Moore.[246]

Occupy Yale

In November 2011, some students started an Occupy Yale movement, discouraging fellow students from joining the finance sector.[247] 25% of Yale graduates join the financial sector.[248][249]

Time Magazine: Person of the Year 2011

OWS was mentioned by Time Magazine in its 2011 selection of "The Protester" as Person of the Year.[250]

Criticism

A number of criticisms of Occupy Wall Street have emerged, both during the movement's most active period and subsequently after. These criticism include a lack of clear goals, false claim as the 99%, a lack of measurable change, trouble conveying its message, a failure to continue its support base, pursuing the wrong audience, and accusations of anti-Semitism.

Lack of clear goals

The Occupy Movement has been criticized for not having a set of clear demands that could be used to prompt formal policy change. This lack of agenda has been cited as the reason why the Occupy Movement fizzled before achieving any specific legislative changes. Although the lack of demands has simultaneously been argued as one of the advantages of the movement,[253] the protesters in Occupy rejected the idea of having only one demand, or a set of demands, and instead represented a host of broad demands that did not specifically allude to a desired policy agenda.[254][255]

Lack of minority representation

Although the movement's primary slogan was "We are the 99%," it was criticized for not encompassing the voice of the entire 99%, specifically lower class individuals and minorities. For example, it was characterized as being overwhelmingly white[256] and poorly representative of the needs of the immigrant population. The lack of African American presence was especially notable, with the movement being criticized in several news outlets and journal articles about its lack of inclusivity and racial diversity.[257][258][259][260]

Lack of measurable change

Some publications mentioned that the Occupy Wall Street Movement failed to spark any true institutional changes in banks and in Corporate America. This idea is supported by the number of scandals that continued to emerge following the financial crisis such as the London Whale incident, the LIBOR-fixing scandal, and the HSBC money laundering discovery. Furthermore, the idea of excess compensation through salaries and bonuses at Wall Street banks continued to be a contentious topic following the Occupy protests, especially as bonuses increased during a period of falling bank profits.[261][262][263]

Trouble conveying its message

Another criticism was the idea that the movement itself was having trouble conveying its actual message. The movement was criticized for demonizing the rich and establishing a theme of class warfare.[264][265] Another issue that was raised was that the Occupy Movement was attempting to indict the entire 1% and argue for wealth redistribution, when in fact, the focus of the movement was centered around upward mobility and fairness for all through government regulation and taxation.[266][267]

Failure to continue its support base

The movement was also criticized for not building a sustainable base of support and instead fading quickly after its initial spark in late 2011 through early 2012.[268] This may be attributed to Occupy's lack of legislative victories, which left the protestors with a lack of measurable goals. It was also argued that the movement was too tied to its base, Zuccotti Park. Evidence of this lies in the fact that when the police evicted the protestors on November 15, the movement largely dissipated.[269][266] While there is evidence that the movement had an enduring impact, protests and direct mentions of the Occupy Movement quickly became uncommon.[270][271][268]

Wrong audience

Many people felt that Occupy had the wrong target in mind, and that Washington, politicians, or the Federal Reserve should have received much of the rebuke[272][273] for ignoring the warning signs leading up to the financial crisis and not taking action more quickly. In addition, the movement was criticized for demonizing banks and the entire financial industry, with the argument being that only a certain portion of Wall Street workers contributed to the actions that eventually sparked the financial crisis.[255][274]

Anti-semitism accusations

Some Occupy Wall Street protests have included anti-zionist and anti-Semitic slogans and signage such as "Jews control Wall Street" or "Zionist Jews who are running the big banks and the Federal Reserve". As a result, the Occupy Wall Street Movement has been confronted with accusations of anti-Semitism by major US media.[275][276][277][278][279]

Subsequent activity

May Day 2012

Occupy Wall Street mounted an ambitious call for a citywide general strike and day of action on May 1, 2012. Recalls journalist Nathan Schneider, "The idea of a general strike had been circulating in the movement since who-knows-when. There was a woman who called for it back on September 17th. Occupy Oakland tried to mount one on November 2nd, with some success and a few broken windows. Soon after, Occupy LA took the lead in announcing a target that seemed sufficiently far off to be feasible, and sufficiently traditional to seem plausible: May Day."[280] Though the day fell short of its wildest ambitions, tens of thousands of people participated in a march through New York City, demonstrating continued support for Occupy Wall Street's cause and concerns.

Occupy Sandy

Occupy Sandy is an organized relief effort created to assist the victims of Hurricane Sandy in the northeastern United States. Occupy Sandy is made up of former and present Occupy Wall Street protesters, other members of the Occupy movement, and former non-Occupy volunteers.[281]

3rd anniversary

Three years after the original occupation, there were fewer people actively involved in Occupy than at its height. However, a number of groups that formed during the occupation or resulted from connections made at that time were still active.[282]

Strike Debt

To celebrate the third anniversary of the occupation of Zuccotti Park, an Occupy Wall Street campaign called "Strike Debt" announced it had wiped out almost $4 million in student loans, amounting to the indebtedness of 2,761 students. The loans were all held by students of Everest College, a for profit college that operates Corinthian Colleges, Inc. which in turn owns Everest University, Everest Institute, Heald College, and WyoTech.

We chose Everest because it is the most blatant con job on the higher ed landscape. It's time for all student debtors to get relief from their crushing burden.

The loans became available when the banks holding defaulted loans put the bad loans up for sale. Once purchased, the group chose to forgive the loans. The funds to purchase the loans came from donations to the Rolling Jubilee Fund, part of the Occupy Student Debt program. As of September 2014, the group claimed to have wiped out almost $19 million in debt.[283]

As of September 2014, Rolling Jubilee claims to have cancelled more than $15 million in medical debt.[284]

Strike Debt, and a successor organization, The Debt Collective, were active in organizing the Corinthian 100 students who struck against Corinthian college, a for-profit school that was shut down by the U.S. Department of Education.[285][286]

Occupy the SEC

Occupy the SEC came together during the occupation. The group seeks to represent the 99% in the regulatory process. They first attracted attention in 2012 when they submitted a 325-page comment letter on the Volcker Rule portion of Dodd Frank.[287]

Alternative Banking

Another offshoot of the Occupy Movement, calling itself the OWS Alternative Banking Group, was established during the occupation of Zuccotti Park in 2011.[288] In 2013, the group published a book titled "Occupy Finance" and distributed copies in Zuccotti Park at the second anniversary and elsewhere.[289] FT Alphaville gave it "two thumbs up for discussable policy proposals" while the New York Times Dealbook called it "a guide to the financial system and the events surrounding the crisis, and it proposes a policy framework that it calls 'popular regulation.'"[290][291] As of 2020, the group continues to meet weekly at Columbia University including a speaker series.[292] From 2015 to 2017, the group published several blog post in the Huffington Post.[293]

Alternative Banking ran Occupy Summer School at the Urban Assembly Institute of Math and Science for Young Women in July 2015.[294]

Influence on movement for higher wages

In 2013, commentators described Occupy Wall Street as having influenced the fast food worker strikes.[295] Occupy Wall Street organizers also contributed to a worker campaign at Hot and Crusty cafe in New York City, helping them obtain higher wages and the right to form a union by working with a worker center.[296] Occupy Wall Street has been credited with reintroducing a strong emphasis on income inequality into broad political discourse and, relatedly, for inspiring the fight for a $15 minimum wage.[297]

See also

- 1932 Bonus army

- 1968 Poor People's Campaign

- 15 October 2011 global protests

- 2011 protests in Spain

- 2011 United States public employee protests

- 2011 Wisconsin protests

- 2013 protests in Brazil

- 2013 protests in Turkey

- 2014 Hong Kong protests

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- List of Occupy movement topics

- List of protests in the 21st century

- Nuit Debout

- Post-democracy

- Radical media

- UC Davis pepper-spray incident

References

Explanatory notes

- Author Dan Berrett writes: "But Occupy Wall Street's most defining characteristics—its decentralized nature and its intensive process of participatory, consensus-based decision-making—are rooted in other precincts of academe and activism: in the scholarship of anarchism and, specifically, in an ethnography of central Madagascar."[8]

- The Huffington Post reports that Graeber and friends discovered that the "General Assembly" had been "taken over by a veteran protest group called the Worker's World Party". Graeber, his companions and others went off on their own to begin their own assembly. Eventually both factions came together. Matt Sledge of the Huffington Post writes: "As the meetings evolved, they became forums for people to air their grievances." There were about 200 activists who organized the ground rules 47 days before the protest began.[22]

Citations

- Engler, Mark (November 1, 2011). "Let's end corruption – starting with Wall Street". New Internationalist Magazine (447). Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- "700 Arrested After Wall Street Protest on N.Y.'s Brooklyn Bridge". Fox News Channel. October 1, 2011. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- "Hundreds of Occupy Wall Street protesters arrested". BBC News. October 2, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- Gabbatt, Adam (October 6, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street: protests and reaction Thursday 6 October". Guardian. London. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- "Wall Street protests span continents, arrests climb". Crain's New York Business. October 17, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011.

- Graeber, David (May 7, 2012). "Occupy's liberation from liberalism: the real meaning of May Day". Guardian. London. Archived from the original on July 16, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- "OccupyWallStreet – About". The Occupy Solidarity Network, Inc. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- "Intellectual Roots of Wall St. Protest Lie in Academe — Movement's principles arise from scholarship on anarchy". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- "A Million Man March on Wall Street". Adbusters. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015.

- Schwartz, Mattathias (November 28, 2011). "Pre-Occupied". Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- Fleming, Andrew (September 27, 2011). "Adbusters sparks Wall Street protest Vancouver-based activists behind street actions in the U.S". The Vancouver Courier. Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- "#OCCUPYWALLSTREET: A shift in revolutionary tactics". Adbusters. Archived from the original on November 15, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- Beeston, Laura (October 11, 2011). "The Ballerina and the Bull: Adbusters' Micah White on 'The Last Great Social Movement'". The Link. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- Schneider, Nathan (September 29, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street: FAQ". The Nation. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- "The Tyee – Adbusters' Kalle Lasn Talks About OccupyWallStreet". Thetyee.ca. October 7, 2011. Archived from the original on February 16, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- Schneider, Nathan. "Some Great Cause". Genius.

- "Wall Street naked performance art ends in arrests". CBC.ca. Associated Press. August 2, 2011. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- RYZIK, MELENA (August 1, 2011). "A Bare Market Lasts One Morning". New York Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- "How a Canadian Culture Magazine Helped Spark Occupy Wall Street". 'Website publisher's name'. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- "Occupy movement confronts limitations as it celebrates one year anniversary : VTDigger". September 18, 2012. Archived from the original on September 23, 2012. Retrieved January 22, 2013.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Bennett, Drake (October 26, 2011). "David Graeber, the Anti-Leader of Occupy Wall Street". Business Week. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

While there were weeks of planning yet to go, the important battle had been won. The show would be run by horizontals, and the choices that would follow—the decision not to have leaders or even designated police liaisons, the daily GAs and myriad working-group meetings that still form the heart of the protests in Zuccotti Park—all flowed from that

- Sledge, Matt (November 10, 2011). "Reawakening The Radical Imagination: The Origins Of Occupy Wall Street". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Saba, Michael (September 17, 2011). "Twitter #occupywallstreet movement aims to mimic Iran". CNN tech. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- "Assange can still Occupy centre stage". Sydney Morning Herald. October 29, 2011. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "'Occupy Wall Street' to Turn Manhattan into 'Tahrir Square'". IBTimes New York. September 17, 2011. Archived from the original on May 21, 2012. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- "From a single hashtag, a protest circled the world". Brisbanetimes.com.au. October 19, 2011. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- Batchelor, Laura (October 6, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street lands on private property". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

Many of the Occupy Wall Street protesters might not realize it, but they got really lucky when they elected to gather at Zuccotti Park in downtown Manhattan

- Schwartz, Mattathias (November 21, 2011). "Map: How Occupy Wall Street Chose Zuccotti Park". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- "Wall Street: 300 Years of Protests". History.com Staff. October 11, 2011. Archived from the original on October 13, 2011.

- Katyal, Sonia K.; Peñalver, Eduardo M. (December 16, 2011). "Occupy's new tactic has a powerful past". CNN. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014.

- Mills, Nicolaus (October 11, 2011). "Wall Street protest's long historical roots". CNN. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- Mills, Nicolaus (November 19, 2011). "A historical precedent that might prove a bonus for Occupy Wall Street". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 24, 2011.

The Great Depression offers a striking parallel to this week's attack on Occupy Wall Street.

- Apps, Peter (October 11, 2011). "Wall Street action part of global Arab Spring?". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- MD Conover & C Davis & E Ferrara & K McKelvey & F Menczer & A Flammini (2013). "The Geospatial Characteristics of a Social Movement Communication Network". PLoS ONE. 8 (3): e55957. arXiv:1306.5473. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...855957C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055957. PMC 3590214. PMID 23483885.

- MD Conover & E Ferrara & F Menczer & A Flammini (2013). "The Digital Evolution of Occupy Wall Street". PLoS ONE. 8 (5): e64679. arXiv:1306.5474. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864679C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064679. PMC 3667169. PMID 23734215.

- Apps, Peter (October 11, 2011). "Wall Street action part of global Arab Spring?". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- Shenker, Jack; Gabbatt, Adam (October 25, 2011). "Tahrir Square protesters send message of solidarity to Occupy Wall Street". The Guardian. London.

Much of the tactics, rhetoric and imagery deployed by protesters has clearly been inspired by this year's political upheavals in the Middle East ...

- Toynbee, Polly (October 17, 2011). "In the City and Wall Street, protest has occupied the mainstream". The Guardian. London.

From Santiago to Tokyo, Ottawa, Sarajevo and Berlin, spontaneous groups have been inspired by Occupy Wall Street.

- "Occupy Wall Street: A protest timeline". November 21, 2011. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014.

A relatively small gathering of young anarchists and aging hippies in lower Manhattan has spawned a national movement. What happened?

- Bloomgarden-Smoke, Kara (January 29, 2012). "What's next for Occupy Wall Street? Activists target foreclosure crisis". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014.

- "Occupy Wall Street's anarchist roots". Aljazeera. Archived from the original on November 30, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

It was only on August 2, when a small group of anarchists and other anti-authoritarians showed up at a meeting called by one such group and effectively wooed everyone away from the planned march and rally to create a genuine democratic assembly, on basically anarchist principles, that the stage was set for a movement that Americans from Portland to Tuscaloosa were willing to embrace.

- Williams, Dana (2012). "The anarchist DNA of Occupy". Contexts. 11 (2): 19. doi:10.1177/1536504212446455.

- Pearce, Matt (June 11, 2012). "Could the end be near for Occupy Wall Street movement?". LA Times. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- Horsley, Scott (January 14, 2012). "The Income Gap: Unfair, Or Are We Just Jealous?". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014.

- ""We Are the 99 Percent" Creators Revealed". Mother Jones and the Foundation for National Progress. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- "Income inequality in America: The 99 percent". The Economist. October 26, 2011. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- Shaw, Hannah; Stone, Chad (May 25, 2011). "Tax Data Show Richest 1 Percent Took a Hit in 2008, But Income Remained Highly Concentrated at the Top. Recent Gains of Bottom 90 Percent Wiped Out". Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved July 30, 2019..

- "By the Numbers". demos.org. Archived from the original on February 1, 2012.

- Alessi, Christopher (October 17, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street's Global Echo". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

The Occupy Wall Street protests that began in New York City a month ago gained worldwide momentum over the weekend, as hundreds of thousands of demonstrators in nine hundred cities protested corporate greed and wealth inequality.

- Jones, Clarence (October 17, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street and the King Memorial Ceremonies". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

The reality is that 'Occupy Wall Street' is raising the consciousness of the country on the fundamental issues of poverty, income inequality, economic justice, and the Obama administration's apparent double standard in dealing with Wall Street and the urgent problems of Main Street: unemployment, housing foreclosures, no bank credit to small business in spite of nearly three trillion of cash reserves made possible by taxpayers funding of TARP.

- Freeland, Chrystia (October 14, 2011). "Wall Street protesters need to find their 'sound bite'". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on October 16, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- Francis, David R. (January 24, 2012). "Thanks to Occupy, rich-poor gap is front and center. See Mitt Romney's tax return". CSMonitor.com. Archived from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- "Six in 10 Support Policies Addressing Income Inequality – ABC News". ABC News. November 9, 2011. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- Seitz, Alex (October 31, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street's Success: Even Republicans Are Talking About Income Inequality". ThinkProgress. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- "Occupy Wall Street and the Political Economy of Inequality" (PDF).

- "Media grows bored of Occupy". Salon. May 7, 2012. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014.

- Luhby, Tami (January 12, 2012). "Romney: Income inequality is just 'envy'". CNN. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013.

- Scola, Nancy (October 5, 2011). "For the Anti-corporate Occupy Wall street demonstrators, the semi-corporate status of Zuccotti Park may be a boon". Capitalnewyork.com. Capital New York Media Group, Inc. Archived from the original on December 4, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- Lowenstein, Roger (October 27, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street: It's Not a Hippie Thing". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013.

- "Volcker Rule: Don't use our deposits for your risky bets | Occupy Design". November 5, 2012. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- Cahill, Petra (October 26, 2011). "Another idea for student loan debt: Make it go away". MSNBC.

- Baum, Geraldine (October 25, 2011). "Student loans add to angst at Occupy Wall Street". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014.

- "Occupy Wall Street vows to carry on after arrests". The San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. March 19, 2012.

- Valdes, Manuel (Associated Press) (December 6, 2011). "Occupy protests move to foreclosed homes". Yahoo! Finance. Archived from the original on January 9, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- Townsend, Mark; O'Carroll, Lisa; Gabbatt, Adam (October 15, 2011). "Occupy protests against capitalism spread around world". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on July 9, 2013.

- Linkins, Jason (October 27, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street: Not Here To Destroy Capitalism, But To Remind Us Who Saved It". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on October 31, 2011.

- Kristof, Nicholas D. (October 26, 2011). "Crony Capitalism Comes Home". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013.

- Taibbi, Matt (October 25, 2011). "Wall Street Isn't Winning – It's Cheating". Rolling Stone Magazine. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- Zizek, Slavoj (October 26, 2011). "Occupy first. Demands come later". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013.

- Struck, Heather (October 19, 2011). "Europe's Occupy Wall Street Pokes At Anti-Capitalism Nerves". Forbes. Archived from the original on December 21, 2011.

- Hoffman, Meredith (October 16, 2011). "New York Times". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013.

- Walsh, Joan (October 20, 2011). "Do we know what OWS wants yet?". Salon.com. Archived from the original on September 2, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Dunn, Mike (October 19, 2011). "'Occupy' May Hold National Assembly In Philadelphia". CBS Philly. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- Peralta, Eyder (February 24, 2012). "Occupy Wall Street Doesn't Endorse Philly Conference". npr.org. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- "Occupy Protesters' One Demand: A New New Deal—Well, Maybe". Mother Jones. October 18, 2011. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Graeber, David. "Occupy Wall Street's Anarchist Roots". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on November 30, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- Elliott, Justin (October 24, 2011). "Judith Butler at Occupy Wall Street". Salon. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2012.; transcript of Butler's talk at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved May 20, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Zuquete, Jose Pedro (2012). ""This is What Democracy Looks Like": Is Representation Under Siege?". New Global Studies. 6. doi:10.1515/1940-0004.1167. hdl:10451/26591.

- "Declaration: Occupy Wall Street Says What It Wants". ABC News. October 4, 2011.

- "Declaration of the Occupation of New York City". New York City General Assembly. Archived from the original on December 20, 2011.

- Kleinfield, N.R.; Buckley, Cara (September 30, 2011). "Wall Street Occupiers, Protesting Till Whenever". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- Downs, Ray (September 18, 2011). "Protesters 'Occupy Wall Street' to Rally Against Corporate America". Christian Post. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013.

- Noveck, Jocelyn (October 10, 2011). "Protesters Want World to Know They're Just Like Us". Long Island Press. AP. Archived from the original on May 7, 2012.

- Goodale, Gloria (November 1, 2011). "Who is Occupy Wall Street? After six weeks, a profile finally emerges". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013.

- "Religion claims its place in Occupy Wall Street". Boston University. 2011. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

Inside, a Buddha statue sits near a picture of Jesus, while a hand-lettered sign in the corner points toward Mecca.

- "RabbiChaimGruber.com B"H". rabbichaimgruber.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2012.

- "Letter to Occupy Wall Street". nycga.net. Archived from the original on January 12, 2013.

- "New York Police Raids Occupy Wall Street Main Encampment". haaretz.com. AP. November 15, 2011.

- "Photo of Rabbi Gruber at Foley Sq., immediately following NYPD clearing of Zuccotti Park on Nov. 15, 2012". macleans.ca. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014.

- "Infographic: Who Is Occupy Wall Street?". FastCompany.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- Parker, Kathleen (November 26, 2011). "Why African Americans aren't embracing Occupy Wall Street". Washington Post. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- "70% of #OWS Supporters are Politically Independent". OccupyWallSt.org. October 19, 2011. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014.

- Captain, Sean (October 19, 2011). "The Demographics Of Occupy Wall Street". Fast Company. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012.

- "Occupy Wall Street Activists Aren't Quite What You Think: Report". Archived from the original on February 9, 2014.

- Berman, Jillian (January 29, 2013). "Occupy Wall Street Activists Aren't Quite What You Think: Report". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013.

- Connelly, Marjorie (October 28, 2011). "Occupy Protesters Down on Obama, Survey Finds". The New York Times.

- http://www.fordham.edu/download/downloads/id/2538/occupy_wall_street_survey.pdf

- Westfeldt, Amy (December 15, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street's center shows some cracks". BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- Hinkle, A. Barton (November 4, 2011). "OWS protesters have strange ideas about fairness". Richmond Times Dispatch. Archived from the original on August 15, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- Penny, Laura (October 16, 2011). "Protest By Consensus". New Statesman. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- "New York City General Assembly website". Archived from the original on February 23, 2014.

- "Occupy Wall Street Moves Indoors With Spokes Council". The New York Observer. November 8, 2011. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014.

- Giove, Candice (January 8, 2012). "OWS has money to burn". New York Post. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012.

- Read, Max. "The Single Largest Benefactor of Occupy Wall Street Is a Mitt Romney Donor". Gawker. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014.

- Burruss, Logan (November 21, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street has money to burn". CNN. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- "Expenditures | Accounting". Accounting.nycga.net. October 15, 2011. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- Firger, Jessica (February 28, 2012). "Occupy Groups Get Funding". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013.

- Nichols, Michelle (March 9, 2012). "Occupy Wall Street in New York running low on cash". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014.

- Cabrera, Claudio. "Is Occupy Wall Street Running Out of Money?". Archived from the original on June 7, 2012.

- Nichols, Michelle (March 9, 2012). "Occupy Wall Street in New York running out of cash". Reuters. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013.

- Firger, Jessica (February 28, 2012). "Occupy Wall Street Movement Gets Corporate Support". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- Simon, Scott. "Ben And Jerry Raise Dough For Occupy Movement". NPR. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014.

- Farnham, Alan. "Springtime for Occupy: Movement's Plans For Coming Weeks and Months". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014.

- Zabriskie, Christian (November 16, 2011). "The Occupy Wall Street Library Regrows in Manhattan". American Libraries. Archived from the original on November 19, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- "ALA alarmed at seizure of Occupy Wall Street library, loss of irreplaceable material" (Press release). American Library Association. November 17, 2011. Archived from the original on November 19, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- "A Library Occupies the Heart of the Occupy Movement". American Libraries Magazine. Archived from the original on November 20, 2011.

- Matthews, Karen (October 7, 2011). "Wall Street functions like a small city". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 9, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

A general assembly of anyone who wants to attend meets twice daily. Because it's hard to be heard above the din of lower Manhattan and because the city is not allowing bullhorns or microphones, the protesters have devised a system of hand symbols. Fingers downward means you disagree. Arms crossed means you strongly disagree. Announcements are made via the "people's mic ... you say it and the people immediately around you repeat it and pass the word along. ... Somewhere between 100 and 200 people sleep in Zuccotti Park. ... Many occupiers were still in their sleeping bags at 9 or 10 am

- Kadet, Anne (October 15, 2011). "The Occupy Economy". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013.

- Oloffson, Kristi (October 12, 2011). "Food Vendors Find Few Customers During Protest". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- GIOVE, CANDICE (November 13, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street costs local businesses $479,400!". New York Post. Archived from the original on February 19, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2011.