Nike, Inc.

Nike, Inc. (/ˈnaɪki/)[2][note 1] is an American multinational corporation that is engaged in the design, development, manufacturing, and worldwide marketing and sales of footwear, apparel, equipment, accessories, and services. The company is headquartered near Beaverton, Oregon, in the Portland metropolitan area. It is the world's largest supplier of athletic shoes and apparel[4] and a major manufacturer of sports equipment, with revenue in excess of US$24.1 billion in its fiscal year 2012 (ending May 31, 2012). As of 2012, it employed more than 44,000 people worldwide. In 2014 the brand alone was valued at $19 billion, making it the most valuable brand among sports businesses.[5] As of 2017, the Nike brand is valued at $29.6 billion.[6] Nike ranked No. 89 in the 2018 Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by total revenue.[7]

Nike's Swoosh logo | |

Nike World Headquarters in Beaverton, Oregon | |

Formerly | Blue Ribbon Sports, Inc. (1964–1971) |

|---|---|

| Public | |

| Traded as | |

| ISIN | US6541061031 |

| Industry | |

| Founded | January 25, 1964 |

| Founders | |

| Headquarters | Beaverton, Oregon, U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products |

|

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 75,400 (2020) |

| Website | nike |

| Footnotes / references [1] | |

The company was founded on January 25, 1964, as Blue Ribbon Sports, by Bill Bowerman and Phil Knight, and officially became Nike, Inc. on May 30, 1971. The company takes its name from Nike, the Greek goddess of victory.[8] Nike markets its products under its own brand, as well as Nike Golf, Nike Pro, Nike+, Air Jordan, Nike Blazers, Air Force 1, Nike Dunk, Air Max, Foamposite, Nike Skateboarding, Nike CR7,[9] and subsidiaries including Brand Jordan, and Converse. Nike also owned Bauer Hockey (later renamed Nike Bauer) from 1995 to 2008, and previously owned Cole Haan Umbro, and Hurley International.[10] In addition to manufacturing sportswear and equipment, the company operates retail stores under the Niketown name. Nike sponsors many high-profile athletes and sports teams around the world, with the highly recognized trademarks of "Just Do It" and the Swoosh logo.

Origins and history

Nike, originally known as Blue Ribbon Sports (BRS), was founded by University of Oregon track athlete Phil Knight and his coach, Bill Bowerman, on January 25, 1964.[11] The company initially operated in Eugene, Oregon as a distributor for Japanese shoe maker Onitsuka Tiger, making most sales at track meets out of Knight's automobile.[12]

According to Otis Davis, a University of Oregon student athlete coached by Bowerman and Olympic gold medalist at the 1960 Summer Olympics, his coach made the first pair of Nike shoes for him, contradicting a claim that they were made for Phil Knight. According to Davis, "I told Tom Brokaw that I was the first. I don't care what all the billionaires say. Bill Bowerman made the first pair of shoes for me. People don't believe me. In fact, I didn't like the way they felt on my feet. There was no support and they were too tight. But I saw Bowerman made them from the waffle iron, and they were mine".[13]

In its first year in business, BRS sold 1,300 pairs of Japanese running shoes grossing $8,000. By 1965, sales had reached $20,000. In 1966, BRS opened its first retail store at 3107 Pico Boulevard in Santa Monica, California. In 1967, due to increasing sales, BRS expanded retail and distribution operations on the East Coast, in Wellesley, Massachusetts.[14]

By 1971, the relationship between BRS and Onitsuka Tiger came to an end. BRS prepared to launch its own line of footwear, which was rebranded as Nike, and would bear the Swoosh newly designed by Carolyn Davidson.[15][16] The Swoosh was first used by Nike on June 18, 1971, and was registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office on January 22, 1974.[17]

In 1976, the company hired John Brown and Partners, based in Seattle, as its first advertising agency.[18] The following year, the agency created the first "brand ad" for Nike, called "There is no finish line", in which no Nike product was shown.[18] By 1980, Nike had attained a 50% market share in the U.S. athletic shoe market, and the company went public in December of that year.[19]

Wieden+Kennedy, Nike's primary ad agency, has worked with Nike to create many print and television advertisements, and Wieden+Kennedy remains Nike's primary ad agency. It was agency co-founder Dan Wieden who coined the now-famous slogan "Just Do It" for a 1988 Nike ad campaign,[20] which was chosen by Advertising Age as one of the top five ad slogans of the 20th century and enshrined in the Smithsonian Institution.[21] Walt Stack was featured in Nike's first "Just Do It" advertisement, which debuted on July 1, 1988.[22] Wieden credits the inspiration for the slogan to "Let's do it", the last words spoken by Gary Gilmore before he was executed.[23]

Throughout the 1980s, Nike expanded its product line to encompass many sports and regions throughout the world.[24] In 1990, Nike moved into its eight-building World Headquarters campus in Beaverton, Oregon.[25] The first Nike retail store, dubbed Niketown, opened in downtown Portland in November of that year.[26]

Phil Knight announced in mid-2015 that he would step down as chairman of Nike in 2016.[27][28] He officially stepped down from all duties with the company on June 30, 2016.[29]

In a company public announcement on March 15, 2018, Nike CEO Mark Parker said Trevor Edwards, a top Nike executive who was seen as a potential successor to the chief executive, was relinquishing his position as Nike's brand president and would retire in August.[30]

In October 2019, John Donahoe was announced as the next CEO, and succeeded Parker on January 13, 2020.[31] In November 2019, the company stopped selling directly through Amazon, focusing more on direct relationships with customers.[32]

Acquisitions

Nike has acquired and sold several apparel and footwear companies over the course of its history. Its first acquisition was the upscale footwear company Cole Haan in 1988,[33] followed by the purchase of Bauer Hockey in 1994.[34] In 2002, Nike bought surf apparel company Hurley International from founder Bob Hurley.[35] In 2003, Nike paid US$309 million to acquire sneaker company Converse.[36] The company acquired Starter in 2004[37] and soccer uniform maker Umbro in 2007.[38]

In order to refocus its business lines, Nike began divesting itself of some of its subsidiaries in the 2000s.[39] It sold Starter in 2007[37] and Bauer Hockey in 2008.[34] The company sold Umbro in 2012 [40] and Cole Haan in 2013.[41] As of 2020, Nike owns only one subsidiary: Converse Inc.

Finance

Nike bought back $8 billion of Nike's class B stock in four years after the current $5 billion buyback program was completed in the second quarter of fiscal year 2013. Up to September 2012, Nike Inc. has bought back $10 billion of stock.[42]

Nike was made a member of the Dow Jones Industrial Average in 2013, when it replaced Alcoa.[43]

On December 19, 2013, Nike's quarterly profit rose due to a 13 percent increase in global orders for merchandise since April of that year. Future orders of shoes or clothes for delivery between December and April, rose to $10.4 billion. Nike shares (NKE) rose 0.6 percent to $78.75 in extended trading.[44]

In November 2015, Nike announced it would initiate a $12 billion share buyback, as well as a two-for-one stock split, with shares to begin trading at the decreased price on December 24.[45] The split will be the seventh in company history.

In June 2018, Nike announced it would initiate a $15 billion share buyback over four years, to begin in 2019 upon completion of the previous buyback program.[46]

For the fiscal year 2018, Nike reported earnings of US$1.933 billion, with an annual revenue of US$36.397 billion, an increase of 6.0% over the previous fiscal cycle. Nike's shares traded at over $72 per share, and its market capitalization was valued at over US$114.5 billion in October 2018.[47]

In March 2020, Nike reported a 5% drop in Chinese sales associated with stores' closure due to the COVID-19 outbreak. It was the first decrease in six years. At the same time, the company's online sales grew by 36% during Q1 of 2020. Also, the sales of personal training apps grew by 80% in China.[48]

| Year | Revenue in mil. USD |

Net income in mil. USD |

Total assets in mil. USD |

Price per share in USD |

Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 13,740 | 1,212 | 8,794 | 8.75 | |

| 2006 | 14,955 | 1,392 | 9,870 | 9.01 | |

| 2007 | 16,326 | 1,492 | 10,688 | 12.14 | |

| 2008 | 18,627 | 1,883 | 12,443 | 13.05 | |

| 2009 | 19,176 | 1,487 | 13,250 | 12.14 | |

| 2010 | 19,014 | 1,907 | 14,419 | 16.80 | |

| 2011 | 20,117 | 2,133 | 14,998 | 19.82 | |

| 2012 | 23,331 | 2,211 | 15,465 | 23.39 | |

| 2013 | 25,313 | 2,472 | 17,545 | 30.50 | 48,000 |

| 2014 | 27,799 | 2,693 | 18,594 | 38.56 | 56,500 |

| 2015 | 30,601 | 3,273 | 21,597 | 53.18 | 62,600 |

| 2016 | 32,376 | 3,760 | 21,379 | 54.80 | 70,700 |

| 2017 | 34,350 | 4,240 | 23,259 | 54.99 | 74,400 |

| 2018 | 36,397 | 1,933 | 22,536 | 72.63 | 73,100 |

Products

Sports equipment

Nike produces a wide range of sports equipment. Their first products were track running shoes. They currently also make shoes, jerseys, shorts, cleats, baselayers, etc. for a wide range of sports, including track and field, baseball, ice hockey, tennis, association football (soccer), lacrosse, basketball, and cricket. Nike Air Max is a line of shoes first released by Nike, Inc. in 1987. Additional product lines were introduced later, such as Air Huarache, which debuted in 1992. The most recent additions to their line are the Nike 6.0, Nike NYX, and Nike SB shoes, designed for skateboarding. Nike has recently introduced cricket shoes called Air Zoom Yorker, designed to be 30% lighter than their competitors'.[49] In 2008, Nike introduced the Air Jordan XX3, a high-performance basketball shoe designed with the environment in mind.

Nike sells an assortment of products, including shoes and apparel for sports activities like association football,[50] basketball, running, combat sports, tennis, American football, athletics, golf, and cross training for men, women, and children. Nike also sells shoes for outdoor activities such as tennis, golf, skateboarding, association football, baseball, American football, cycling, volleyball, wrestling, cheerleading, aquatic activities, auto racing, and other athletic and recreational uses. Nike recently teamed up with Apple Inc. to produce the Nike+ product that monitors a runner's performance via a radio device in the shoe that links to the iPod nano. While the product generates useful statistics, it has been criticized by researchers who were able to identify users' RFID devices from 60 feet (18 m) away using small, concealable intelligence motes in a wireless sensor network.[51][52]

In 2004, Nike launched the SPARQ Training Program/Division.[53] Some of Nike's newest shoes contain Flywire and Lunarlite Foam to reduce weight.[54] The Air Zoom Vomero running shoe, introduced in 2006 and currently in its 11th generation, featured a combination of groundbreaking innovations including a full-length air cushioned sole,[55] an external heel counter, a crashpad in the heel for shock absorption, and Fit Frame technology for a stable fit.[56]

Nike Vaporfly

The Nike Vaporfly first came out in 2017 and their popularity, along with its performance, prompted a new series of running shoes.[57][58] The Vaporfly series has a new technological composition that has revolutionized long-distance running since studies have shown that these shoes can improve run times up to 4.2%.[58] The composition of the sole contains a foamy material, Pebax, that Nike has altered and now calls it ZoomX (which can be found in other Nike products as well). Pebax foam can also be found in airplane insulation and is "squishier, bouncier, and lighter" than foams in typical running shoes.[58] In the middle of the ZoomX foam there is a full-length carbon fiber plate "designed to generate extra spring in every step".[58] At the time of this writing Nike had just released its newest product from the Vaporfly line, the Nike ZoomX Vaporfly NEXT%, which was marketed as "the fastest shoe we’ve ever made" using Nike's "two most innovative technologies, Nike ZoomX foam and VaporWeave material".[59]

Street fashions

The Nike brand, with its distinct V-shaped logo, quickly became regarded as a status symbol[60] in modern urban fashion and hip-hop fashion[61] due to its association with success in sport.[62] Beginning in the 1980s, various items of Nike clothing became staples of mainstream American youth fashion, especially tracksuits, shell suits, baseball caps, Air Jordans, Air Force 1's, and Air Max running shoes[63] with thick, air cushioned rubber soles and contrasting blue, yellow, green, white, or red trim.[64] Limited edition sneakers and prototypes with a regional early release were known as Quickstrikes,[65] and became highly desirable items[66] for teenage members of the sneakerhead subculture.[67]

By the 1990s and 2000s, American and European teenagers[68] associated with the preppy[69] or popular clique[70] began combining these sneakers,[71] leggings, sweatpants, crop tops,[72] and tracksuits with regular casual chic[73] street clothes[74] such as jeans, skirts, leg warmers, slouch socks, and bomber jackets. Particularly popular were the unisex spandex Nike Tempo compression shorts[75] worn for cycling and running, which had a mesh lining, waterproofing, and, later in the 2000s, a zip pocket for a Walkman or MP3 player.[76]

From the late 2000s into the 2010s, Nike Elite basketball socks began to be worn as everyday clothes by hip-hop fans and young children.[77] Originally plain white or black, these socks had special shock absorbing cushioning in the sole[78] plus a moisture wicking upper weave.[79] Later, Nike Elite socks became available in bright colors inspired by throwback basketball uniforms,[80] often with contrasting bold abstract designs, images of celebrities,[81] and freehand digital print[82] to capitalise upon the emerging nostalgia for 1990s fashion.

In 2015, a new self-lacing shoe was introduced. Called the Nike Mag, which are replicas of the shoes featured in Back to the Future Part II, it had a preliminary limited release, only available by auction with all proceeds going to the Michael J. Fox Foundation.[83] This was done again in 2016.[84]

Nike have introduced a premium line, focused more on streetwear than sports wear called NikeLab.[85]

In March 2017, Nike announced its launch of a plus-size clothing line, which will feature new sizes 1X through 3X on more than 200 products.[86] Another significant development at this time was the Chuck Taylor All-Star Modern, an update of the classic basketball sneaker that incorporated the circular knit upper and cushioned foam sole of Nike's Air Jordans.[87]

Collectibles

On 23 July 2019 a pair of Nike Inc. running shoes sold for $437,500 at a Sotheby's auction. The so-called "Moon Shoes" were designed by Nike co-founder and track coach Bill Bowerman for runners participating in the 1972 Olympics trials. The buyer was Miles Nadal, a Canadian investor and car collector, who had just paid $850,000 for a group of 99 rare of limited collection pairs of sport shoes. The purchase price was the highest for one pair of sneakers, the previous record being $190,373 in 2017 for a pair of signed Converse shoes in California, said to have been worn by Michael Jordan during the 1984 basketball final of the Olympics that year.[88]

Headquarters

Nike's world headquarters are surrounded by the city of Beaverton but are within unincorporated Washington County. The city attempted to forcibly annex Nike's headquarters, which led to a lawsuit by Nike, and lobbying by the company that ultimately ended in Oregon Senate Bill 887 of 2005. Under that bill's terms, Beaverton is specifically barred from forcibly annexing the land that Nike and Columbia Sportswear occupy in Washington County for 35 years, while Electro Scientific Industries and Tektronix receive the same protection for 30 years.[89] Nike is planning to build a 3.2 million square foot expansion to its World Headquarters in Beaverton.[90] The design will target LEED Platinum certification and will be highlighted by natural daylight, and a gray water treatment center.[90]

Controversy

Nike has contracted with more than 700 shops around the world and has offices located in 45 countries outside the United States.[91] Most of the factories are located in Asia, including Indonesia, China, Taiwan, India,[92] Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan, Philippines, and Malaysia.[93] Nike is hesitant to disclose information about the contract companies it works with. However, due to harsh criticism from some organizations like CorpWatch, Nike has disclosed information about its contract factories in its Corporate Governance Report.

Sweatshops

Nike has been criticized for contracting with factories (known as Nike sweatshops) in countries such as China, Vietnam, Indonesia and Mexico. Vietnam Labor Watch, an activist group, has documented that factories contracted by Nike have violated minimum wage and overtime laws in Vietnam as late as 1996, although Nike claims that this practice has been stopped.[94] The company has been subject to much critical coverage of the often poor working conditions and exploitation of cheap overseas labor employed in the free trade zones where their goods are typically manufactured. Sources for this criticism include Naomi Klein's book No Logo and Michael Moore documentaries.

Campaigns have been taken up by many colleges and universities, especially anti-globalisation groups, as well as several anti-sweatshop groups such as the United Students Against Sweatshops.[95]

As of July 2011, Nike stated that two-thirds of its factories producing Converse products still do not meet the company's standards for worker treatment. A July 2011 Associated Press article stated that employees at the company's plants in Indonesia reported constant abuse from supervisors.[96]

Child labor allegations

During the 1990s, Nike faced criticism for the use of child labor in Cambodia and Pakistan in factories it contracted to manufacture soccer balls. Although Nike took action to curb or at least reduce the practice, they continue to contract their production to companies that operate in areas where inadequate regulation and monitoring make it hard to ensure that child labor is not being used.[97]

In 2001, a BBC documentary uncovered occurrences of child labor and poor working conditions in a Cambodian factory used by Nike.[98] The documentary focused on six girls, who all worked seven days a week, often 16 hours a day.

Strike in China factory

In April 2014, one of the biggest strikes in mainland China took place at the Yue Yuen Industrial Holdings Dongguan shoe factory, producing amongst others for Nike. Yue Yuen did underpay an employee by 250 yuan (40.82 US Dollars) per month. The average salary at Yue Yuen is 3000 yuan per month. The factory employs 70,000 people. This practice was in place for nearly 20 years.[99][100][101]

Paradise Papers

On 5 November 2017, the Paradise Papers, a set of confidential electronic documents relating to offshore investment, revealed that Nike is among the corporations that used offshore companies to avoid taxes.[102][103][104]

Appleby documents detail how Nike boosted its after-tax profits by, among other maneuvers, transferring ownership of its Swoosh trademark to a Bermudan subsidiary, Nike International Ltd. This transfer allowed the subsidiary to charge royalties to its European headquarters in Hilversum, Netherlands, effectively converting taxable company profits to an account payable in tax-free Bermuda.[105] Although the subsidiary was effectively run by executives at Nike's main offices in Beaverton, Oregon—to the point where a duplicate of the Bermudan company's seal was needed—for tax purposes the subsidiary was treated as Bermuda. Its profits were not declared in Europe and came to light only because of a mostly unrelated case in US Tax Court, where papers filed by Nike briefly mention royalties in 2010, 2011 and 2012 totaling $3.86 billion.[105] Under an arrangement with Dutch authorities, the tax break was to expire in 2014, so another reorganization transferred the intellectual property from the Bermudan company to a Dutch commanditaire vennootschap or limited partnership, Nike Innovate CV. Dutch law treats income earned by a CV as if it had been earned by the principals, who owe no tax in the Netherlands if they do not reside there.[105]

Colin Kaepernick

In September 2018, Nike announced it had signed former American football quarterback Colin Kaepernick, noted for his controversial decision to kneel during the playing of the US national anthem, to a long-term advertising campaign.[106] According to Charles Robinson of Yahoo! Sports, Kaepernick and Nike agreed to a new contract despite the fact Kaepernick has been with the company since 2011 and said that "interest from other shoe companies" played a part in the new agreement. Robinson said the contract is a "wide endorsement" where Kaepernick will have his own branded line including shoes, shirts, jerseys and more. According to Robinson, Kaepernick signed a "star" contract that puts him level with a "top-end NFL player" worth millions per year plus royalties.[107] In response, some people set fire to their own Nike-branded clothes and shoes or cut the Nike swoosh logo out of their clothes, and the Fraternal Order of Police called the advertisement an "insult";[108][109][110] others, such as LeBron James,[111] Serena Williams,[112] and the National Black Police Association,[110] praised Nike for its campaign. The College of the Ozarks removed Nike from all their athletic uniforms in response.[113]

During the following week, Nike's stock price fell 2.2%, even as online orders of Nike products rose 27% compared with the previous year.[114] In the following three months, Nike reported a rise in sales.[115]

In July 2019, Nike released a shoe featuring a Betsy Ross flag called the Air Max 1 Quick Strike Fourth of July trainers. The trainers were designed to celebrate Independence Day. The model was subsequently withdrawn after Colin Kaepernick told the brand he and others found the flag offensive because of its association with slavery.[116][117][118]

Nike's decision to withdraw the product drew criticism from Arizona's Republican Governor, Doug Ducey, and Texas's Republican Senator Ted Cruz.[119] Nike's decision was praised by others due to the use of the flag by white nationalists,[118] but the Anti-Defamation League's Center on Extremism has declined to add the flag to its database of "hate symbols."[120]

Hong Kong protests

U.S. Vice President Mike Pence criticized Nike for "siding with the Chinese Communist Party and silencing free speech".[121]

Nike Vaporfly Shoe

On January 31, 2020, the World Athletics issued new guidelines concerning shoes to be used in the upcoming Tokyo 2020 Olympics.[122] These updates came in response to criticisms concerning technology in the Nike Vaporfly running shoes, which had been submitted beginning around 2017–2018.[123] These criticisms stated that the shoes provided athletes with an unfair advantage over their opponents and some critics considered it to be a form of mechanical doping.[58][124] According to Nike funded research, the shoes can improve efficiency by up to 4.2%[58] and runners who have tested the shoe are saying that it causes reduced soreness in the legs; sports technologist Bryce Dyer attributes this to the ZoomX and carbon fiber plate since it absorbs the energy and "spring[s] runners forward".[124] Some athletes, scientists, and fans have compared this to the 2008 LAZR swimsuit controversy.[125]

Some of the major changes in the guidelines that have come about as a result of these criticisms include that the "sole must be no thicker than 40mm" and that "the shoe must not contain more than one rigid embedded plate or blade (of any material) that runs either the full length or only part of the length of the shoe. The plate may be in more than one part but those parts must be located sequentially in one plane (not stacked or in parallel) and must not overlap". The components of the shoes are not the only thing that had major changes; starting April 30, 2020, "any shoe must have been available for purchase by any athlete on the open retail market (online or in store) for a period of four months before it can be used in competition".[122] Prior to these new guidelines World Athletics reviewed the Vaporfly shoes and "concluded that there is independent research that indicates that the new technology incorporated in the soles of road and spiked shoes may provide a performance advantage" and that it recommends further research to "establish the true impact of [the Vaporfly] technology."[122]

Environmental record

According to the New England-based environmental organization Clean Air-Cool Planet, Nike ranked among the top three companies (out of 56) in a survey of climate-friendly companies in 2007.[126] Nike has also been praised for its Nike Grind program (which closes the product lifecycle) by groups like Climate Counts.[127] One campaign that Nike began for Earth Day 2008 was a commercial that featured basketball star Steve Nash wearing Nike's Trash Talk Shoe, which had been constructed in February 2008 from pieces of leather and synthetic leather waste from factory floors. The Trash Talk Shoe also featured a sole composed of ground-up rubber from a shoe recycling program. Nike claims this is the first performance basketball shoe that has been created from manufacturing waste, but it only produced 5,000 pairs for sale.[128]

Another project Nike has begun is called Nike's Reuse-A-Shoe program. This program, started in 1993, is Nike's longest-running program that benefits both the environment and the community by collecting old athletic shoes of any type in order to process and recycle them. The material that is produced is then used to help create sports surfaces such as basketball courts, running tracks, and playgrounds.[129]

A project through the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found workers were exposed to toxic isocyanates and other chemicals in footwear factories in Thailand. In addition to inhalation, dermal exposure was the biggest problem found. This could result in allergic reactions including asthmatic reactions.[130][131]

Marketing strategy

Nike promotes its products by sponsorship agreements with celebrity athletes, professional teams and college athletic teams.

Advertising

In 1982, Nike aired its first three national television ads, created by newly formed ad agency Wieden+Kennedy (W+K), during the broadcast of the New York Marathon.[132] The Cannes Advertising Festival has named Nike its Advertiser of the Year in 1994 and 2003, making it the first company to receive that honor twice.[133]

Nike also has earned the Emmy Award for best commercial twice since the award was first created in the 1990s. The first was for "The Morning After," a satirical look at what a runner might face on the morning of January 1, 2000 if every dire prediction about the Y2K problem came to fruition.[134] The second was for a 2002 spot called "Move," which featured a series of famous and everyday athletes in a variety of athletic pursuits.[135]

Beatles song

Nike was criticized for its use of the Beatles song "Revolution" in a 1987 commercial against the wishes of Apple Records, the Beatles' recording company. Nike paid US$250,000 to Capitol Records Inc., which held the North American licensing rights to the recordings, for the right to use the Beatles' rendition for a year.

Apple Records sued Nike Inc., Capitol Records Inc., EMI Records Inc. and Wieden+Kennedy for $15 million.[136] Capitol-EMI countered by saying the lawsuit was "groundless" because Capitol had licensed the use of "Revolution" with the "active support and encouragement of Yoko Ono, a shareholder and director of Apple Records."

Nike discontinued airing ads featuring "Revolution" in March 1988. Yoko Ono later gave permission to Nike to use John Lennon's "Instant Karma" in another advertisement.

New media marketing

Nike was an early adopter of internet marketing, email management technologies, and using broadcast and narrowcast communication technologies to create multimedia marketing campaigns.

Minor Threat advertisement

In late June 2005, Nike received criticism from Ian MacKaye, owner of Dischord Records, guitarist/vocalist for Fugazi and The Evens, and front man of the defunct punk band Minor Threat, for appropriating imagery and text from Minor Threat's 1981 self-titled album's cover art in a flyer promoting Nike Skateboarding's 2005 East Coast demo tour.

On June 27, Nike Skateboarding's website issued an apology to Dischord, Minor Threat, and fans of both and announced that they have tried to remove and dispose of all flyers. They stated that the people who designed it were skateboarders and Minor Threat fans themselves who created the advertisement out of respect and appreciation for the band.[137] The dispute was eventually settled out of court between Nike and Minor Threat.

Nike 6.0

As part of the 6.0 campaign, Nike introduced a new line of T-shirts that include phrases such as "Dope", "Get High" and "Ride Pipe" – sports lingo that is also a double entendre for drug use. Boston Mayor Thomas Menino expressed his objection to the shirts after seeing them in a window display at the city's Niketown and asked the store to remove the display. "What we don't need is a major corporation like Nike, which tries to appeal to the younger generation, out there giving credence to the drug issue," Menino told The Boston Herald. A company official stated the shirts were meant to pay homage to extreme sports, and that Nike does not condone the illegal use of drugs.[138] Nike was forced to replace the shirt line.[139]

NBA uniform deal

In June 2015, Nike signed an 8-year deal with the NBA to become the official uniform supplier for the league, beginning with the 2017–18 season. The brand took over for Adidas, who provided the uniforms for the league since 2006. Unlike previous deals, Nike's logo appear on NBA jerseys – a first for the league.[140] The only exception is the Charlotte Hornets, owned by longtime Nike endorser Michael Jordan, which instead uses the Jumpman logo associated with Jordan-related merchandise.[141]

Sponsorship

Nike sponsors top athletes in many sports to use their products and promote and advertise their technology and design. Nike's first professional athlete endorser was Romanian tennis player Ilie Năstase.[142] The first track endorser was distance runner Steve Prefontaine. Prefontaine was the prized pupil of the company's co-founder, Bill Bowerman, while he coached at the University of Oregon. Today, the Steve Prefontaine Building is named in his honor at Nike's corporate headquarters. Nike has only made one statue of its sponsored athletes and it is of Steve Prefontaine.[143]

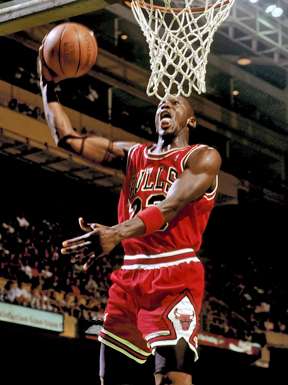

Nike has also sponsored many other successful track and field athletes over the years, such as Sebastian Coe, Carl Lewis, Jackie Joyner-Kersee, Michael Johnson and Allyson Felix. The signing of basketball player Michael Jordan in 1984, with his subsequent promotion of Nike over the course of his career, with Spike Lee as Mars Blackmon, proved to be one of the biggest boosts to Nike's publicity and sales.[144]

Nike is a major sponsor of the athletic programs at Penn State University and named its first child care facility after Joe Paterno when it opened in 1990 at the company's headquarters. Nike originally announced it would not remove Paterno's name from the building in the wake of the Penn State sex abuse scandal. After the Freeh Report was released on July 12, 2012, Nike CEO Mark Parker announced the name Joe Paterno would be removed immediately from the child development center. A new name has yet to be announced.[147][148]

in the early 1990s Nike made a strong push into the association football business making endorsement deals with famous and charismatic players such as Romario, Eric Cantona or Edgar Davids. They continued the growth in the sport by signing more top players including: Ronaldo, Ronaldinho, Francesco Totti, Thierry Henry, Didier Drogba, Andrés Iniesta, Wayne Rooney and still have many of the sport's biggest stars under their name, with Cristiano Ronaldo, Zlatan Ibrahimović, Neymar, Harry Kane, Eden Hazard and Kylian Mbappé among others.[149]

In 2012, Nike carried a commercial partnership with the Asian Football Confederation.[150] In August 2014, Nike announced that they will not renew their kit supply deal with Manchester United after the 2014–15 season, citing rising costs.[151] Since the start of the 2015–16 season, Adidas has manufactured Manchester United's kit as part of a world-record 10-year deal worth a minimum of £750 million.[152] Nike still has many of the top teams playing in their uniforms, including: FC Barcelona, Paris Saint-Germain and Liverpool (the latter from the 2020–21 season),[153] and the national teams of Brazil, France, England, Portugal and the Netherlands among many others.

Nike has been the sponsor for many top ranked tennis players. Brand's commercial success in the sport went hand in hand with the endorsement deals signed with the biggest and the world's most charismatic stars and number one ranked players of the subsequent eras, including John McEnroe in the 1980s, Andre Agassi and Pete Sampras in the 1990s and Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, Serena Williams and Maria Sharapova with the start of the XXI century.[154]

Nike has sponsored Tiger Woods for much of his career, and remained on his side amid the controversies that shaped the golfer's career.[155] In January 2013, Nike signed Rory McIlroy, the then No 1 golfer in the world to a 10-year sponsorship deal worth $250 million. The deal includes using Nike's range of golf clubs, a move Nick Faldo previously described as "dangerous" for McIlroy's game.[156]

Nike has been the official kit sponsor for the Indian cricket team since 2005.[157][158] On February 21, 2013, Nike announced it suspended its contract with South African limbless athlete Oscar Pistorius, due to his being charged with premeditated murder.[159]

Nike consolidated its position in basketball in 2015 when it was announced that the company would sign an 8-year deal with the NBA, taking over from the league's previous uniform sponsor, Adidas. The deal required all franchise team members to wear jerseys and shorts with the Swoosh logo, beginning with the 2017/18 season.[160] After the success of partnership with Jordan, which resulted in the creation of the unique Air Jordan brand, Nike has continued to build partnership with the biggest names in basketball. Lebron James was given the Slogan "We are All Witnesses" when he signed with Nike. Similar to "Air Jordan", LeBron's brand became massively popular. The slogan was an extremely accurate way to describe the situation LeBron was heading into in the NBA he was expected to be the new king of the NBA.[161] Some have had signature shoes designed for them, including Kobe Bryant, Jason Kidd, Vince Carter and more recently LeBron James, Kevin Durant and Paul George, among others.[162][163][164][165][166]

A news report originating from CNN reported that Nike spent $11.5 billion, nearly a third of its sales, on marketing and endorsement contracts in the year 2018. Nike and its Jordan brand sponsored 85 men's and women's basketball teams in the NCAA tournament.[167]

Ties with the University of Oregon

The company maintains strong ties, both directly and indirectly (through partnership with Phil Knight), with the University of Oregon. Nike designs the University of Oregon football program's team attire. New unique combinations are issued before every game day.[168] Tinker Hatfield, who also redesigned the university's logo, leads this effort.[169]

More recently, the corporation donated $13.5 million towards the renovation and expansion of Hayward Field.[170]

Phil Knight has invested substantial personal funds towards developing and maintaining the university's athletic apparatus.[171] His university projects often involve input from Nike designers and executives, such as Tinker Hatfield.[169]

Causes

In 2012, Nike is listed as a partner of the (PRODUCT)RED campaign together with other brands such as Girl, American Express, and Converse. The campaign's mission is to prevent the transmission of the HIV virus from mother to child by 2015 (the campaign's byline is "Fighting For An AIDS Free Generation"). The company's goal is to raise and send funds, for education and medical assistance to those who live in areas heavily effected by AIDS.[172]

Program

The Nike Community Ambassador Program, allows Nike employees from around the world to go out and give to their community. Over 3,900 employees from various Nike stores have participated in teaching children to be active and healthy.[173]

See also

- Nike timeline

- Breaking2 - A project by Nike to break the 2 hour marathon barrier.

- List of companies based in Oregon

Notes

- The pronunciations of "Nike"[3] include /ˈnaɪki/ NY-kee officially and in the US, as well as /naɪk/ NYKE outside of the US.

References

- "US SEC: 2020 Form 10-K NIKE, Inc". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Published letter between NIKE to Philip H. Knight,https://static.independent.co.uk/s3fs-public/thumbnails/image/2014/06/02/10/nikey.JPG (2014)

- It's official: Nike rhymes with spiky – and you're saying all these wrong too". The Guardian. Retrieved December 21, 2014

- Sage, Alexandria (June 26, 2008). "Nike profit up but shares tumble on U.S. concerns". Reuters. Retrieved July 10, 2008.

- Ozanian, Mike (July 10, 2014). "The Forbes Fab 40: The World's Most Valuable Sports Brands 2014". Forbes. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- null. "Nike - pg.16". Forbes. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- "Fortune 500 Companies 2018: Who Made the List". Fortune. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- Levinson, Philip. "How Nike almost ended up with a very different name". Business Insider. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- "Nike CR7". Nike, Inc.

- "Nike sells Bauer Hockey for $200 Million". The Sports Network. February 21, 2008. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- O'Reilly, Lara. "11 Things Hardly Anyone Knows About Nike". Business Insider. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- O' Reilly, Lara (November 4, 2014). "11 Things Hardly Anyone Knows About Nike." BusinessInsider.com. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- Hague, Jim (May 14, 2006). "Truant officer was Olympic hero Emerson High has gold medalist in midst". The Hudson Reporter. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- "Nike Company History".

- "Logos that became legends: Icons from the world of advertising". The Independent. London. January 4, 2008. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- Meyer, Jack (August 14, 2019). "History of Nike: Timeline and Facts". TheStreet. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- "Registration Number 72414177". TSDR. U.S. Patent & Trademark Office. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- "Nike Inc". adage.com. September 15, 2003. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- "Nike Inc | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- Bella, Timothy (September 4, 2018). "'Just Do It': The surprising and morbid origin story of Nike's slogan". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- "Ad Age Advertising Century: Top 10 Slogans". adage.com. March 29, 1999. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- "Nike's 'Just Do It' slogan celebrates 20 years". OregonLive.com. July 18, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- Peters, Jeremy W. (August 19, 2009). "The Birth of 'Just Do It' and Other Magic Words". The New York Times. Retrieved September 30, 2009.

- "History of Nike". www.newitts.com. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- Brettman, Allan (February 2, 2013). "As Nike looks to expand, it already has a 22-building empire". The Oregonian. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

The first phase of the Nike World Headquarters campus opened in 1990 and included eight buildings. Now, there are 22 buildings.

- Brettman, Allan (October 27, 2011). "NikeTown Portland to close forever [at its original location] on Friday". The Oregonian. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- Wightman-Stone, Danielle (July 1, 2015). "Nike chairman Phil Knight to step down in 2016". FashionUnited. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- Bain, Marc (June 30, 2015). "How Phil Knight turned the Nike brand into a global powerhouse". Quartz. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- Vinton, Kate (June 30, 2016). "Nike Cofounder And Chairman Phil Knight Officially Retires From The Board". FashionUnited. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- Hsu, Tiffany (March 15, 2018). "Nike Executive Resigns; C.E.O. Addresses Workplace Behavior Complaints". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Turner, Nick (October 22, 2019). "Nike Taps EBay Veteran John Donahoe to Succeed Parker as CEO". Bloomberg LP. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- Hanbury, Mary (November 13, 2019). "Nike confirms that it is no longer selling its products on Amazon". Business Insider. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- "Cole-Haan to Nike For $80 Million". The New York Times. April 26, 1988. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Austen, Ian (February 22, 2008). "Hockey Fan, and Investor, Buys Bauer From Nike". The New York Times. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Connelly, Laylan (January 22, 2013). "Bob Hurley: Success built on everyone's inner surfer". Orange County Register. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Partlow, Joshua (July 2003). "Nike Drafts An All Star". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- "Nike unloads Starter for $60M". Portland Business Journal. November 15, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Townsend, Matt (October 24, 2012). "Iconix Brand Buys Nike's Umbro Soccer Unit for $225 Million". BloombergBusinessweek. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Dezember, Ryan (October 24, 2012). "After Umbro, Nike Turns to Cole Haan Sale". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- Stevens, Suzanne (December 3, 2012). "Nike completes Umbro sale to Iconix". Portland Business Journal. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "Nike completes Cole Haan sale". Portland Business Journal. February 4, 2013. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Prasad, Sakthi (September 20, 2012). "Nike approves $8 billion share repurchase program". Reuters.

- GOLDWYN BLUMENTHAL, ROBIN. "Alcoa's CEO Is Remaking the Industrial Giant". Barron's. Barron's. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- "Nike Fiscal 2nd-Quarter Profit Jumps 40 Percent". December 19, 2013.

- Scholer, Kristen (November 20, 2015). "What Nike's Two-For-One Stock Split Means for the Dow". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- "Nike surges after beating on earnings and announcing $15 billion in buybacks (NKE) | Markets Insider". markets.businessinsider.com. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- "NIKE Revenue 2006-2018 | NKE". www.macrotrends.net. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- Harper, Justin (March 25, 2020). "Nike turns to digital sales during China shutdown". BBC News. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "Nike launches cricket shoe Air Zoom Yorker". The Hindu Business Line. September 2, 2006. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- "Nike Air Zoom Control II FS Futsal Shoes at Soccer Pro". Soccerpro.com. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- T. Scott Saponas; Jonathan Lester; Carl Hartung; Tadayoshi Kohno. "Devices That Tell On You: The Nike+iPod Sport Kit" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 7, 2012.

- Tom Espiner (December 13, 2006). "Nike+iPod raises RFID privacy concerns". CNet.

- "SPARQ - Nike Performance Summitt". SPECTRUM, Inc. June 4, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- "Latest materials improve sportswear performance". ICIS Chemical Business. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- 20th Anniversary of Air Zoom

- New Air Zoom Vomero

- "Factbox: Nike's Vaporfly running shoes and tumbling records". Reuters. January 24, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- Safdar, Rachel Bachman and Khadeeja (January 31, 2020). "Nike Vaporfly Shoes Won't Be Banned From Olympics". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- "Nike Vaporfly. Featuring the new Vaporfly NEXT%". Nike.com. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- McKee, Alan (April 15, 2008). Beautiful things in popular culture. Wiley. p. 106. ISBN 9781405178556. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- Goldman, Peter; Papson, Stephen (1998). Nike Culture: The Sign of the Swoosh. SAGE. pp. 88, 102. ISBN 9780761961499. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- Carbasho, Tracy (2010). Nike. ABC-CLIO. p. 17. ISBN 9781598843439. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- "Nike's High-Stepping Air Force". Popular Mechanics. August 1987. p. 33. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- "Nike advert". Working Mother. p. 76. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- GQ guide to selling sneakers

- High Snob

- Sneaker Watch

- How teens spend money

- Brand failures

- Dress to express

- Queen of the basic bitches

- Vogue magazine

- Nike vs J Crew

- Exeter basic bitch

- "Nike Tempo trend". Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- Running for beginners. Imagine. p. 240. ISBN 9781908955111. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- Young and stylish

- Introducing the Nike Elite

- Colorful socks no longer a fad

- "Dr Jays". Archived from the original on April 16, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- Aaliyah, Nino Brown and Freddy Kruger socks

- Digital ink printed socks

- "The 2015 Nike Mag". NIKE, Inc. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- Rooney, Kyle (October 21, 2016). "The Michael J. Fox Foundation does raffle with Nike to raise awareness for Parkinson's disease". Hotnewhiphop. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- "NikeLab". www.nike.com. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- Lekach, Sasha. "Nike finally releases plus-size clothing line for women". Mashable. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- Nike unveils converse modern

- "Nike shoes race to $437,500 world record auction price for sneakers". Reuters. July 24, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- "Appellate court rejects Beaverton annexation | The Oregonian Extra". Blog.oregonlive.com. June 16, 2006. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- Siemers, Erik (January 20, 2016). "A first look at Nike's $380M-plus HQ expansion (Renderings)". American City Business Journals.

- NikeBiz | Investors | Corporate Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "India's 50 most trusted brands". rediff.com. January 20, 2011.

- Archived June 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Nike Labor Practices in Vietnam Archived April 18, 2001, at the Wayback Machine

- "Sweatfree Campus Campaign Launch". Studentsagainstsweatshops.org. September 28, 2005. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- Associated Press, "Nike still dogged by worker abuses", Japan Times, July 15, 2011, p. 4.

- "MIT" (PDF). Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- Sun Thyda, 12 (October 15, 2000). "Programmes | Panorama | Archive | Gap and Nike: No Sweat? October 15, 2000". BBC News. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- More than ten thousand workers stage strike at massive Dongguan shoe factory, April 14, 2014

- Yue Yuen shoe factory workers' strike at Dongguan plants continues, April 17, 2014.

- Yue Yuen strikers vow to continue until benefit contribution deficit paid in full, South China Morning Post, April 18, 2013.

- "'Paradise papers' expose tax evasion schemes of the global elite". Deutsche Welle. 5 November 2017.

- "So lief die SZ-Recherche". Süddeutsche Zeitung. 5 November 2017.

- "Offshore Trove Exposes Trump-Russia Links And Piggy Banks Of The Wealthiest 1 Percent". International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. November 5, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- Simon Bowers (November 6, 2017). "How NikeStays One Step Ahead of the Regulators: When One Tax Loophole Closes, Another Opens". ICIJ. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- Einhorn, Bruce (September 4, 2018). "Nike Falls as Critics Fume on Social Media Over Kaepernick Deal". Bloomberg.

- Daniels, Tim (September 3, 2018). "Colin Kaepernick Named Face of Nike's 30th Anniversary of 'Just Do It' Campaign". Bleacher Report.

- "People Are Already Burning Their Nikes in Response to the Colin Kaepernick Ad". Esquire. September 4, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- "People are destroying their Nike shoes and socks to protest Nike's Colin Kaepernick ad campaign". Business Insider France (in French). Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- Golding, Shenequa (September 6, 2018). "The National Black Police Association Is In Full Support Of Nike's Colin Kaepernick Ad". Vibe. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- Cancian, Dan (September 6, 2018). "LeBron 'Stands with Nike' in Support of Colin Kaepernick's Campaign". Newsweek. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- "Serena Williams supports Nike's decision to endorse Colin Kaepernick". Global News. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- Wheeler, Wyatt D. (September 5, 2018). "College of the Ozarks drops Nike, will 'choose country over company'". Springfield News-Leader. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- Novy-Williams, Eben. "Nike Orders Rose in Four-Day Period After Kaepernick Ad Debut". Bloomberg. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- "Nike hit by conservative backlash over 'racist trainer'". BBC. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- Safdar, Khadeeja; Beaton, Andrew (July 1, 2019). "Nike Nixes 'Betsy Ross Flag' Shoe After Kaepernick Intervenes". Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- "Nike pulls Fourth of July trainers after Colin Kaepernick 'raises concerns'". The Independent. July 2, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- "Nike 'pulls Betsy Ross flag trainer after Kaepernick complaint'". BBC News. July 2, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- "Nike Pulls 'Betsy Ross Flag' Sneakers After Kaepernick Complaint". July 2, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- Goldberg, Jonah (July 15, 2019). "Nike fans the flames of the culture war". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- "Pence backs Hong Kong protests in China speech, slams NBA and Nike". Reuters. October 24, 2019.

- "World Athletics modifies rules governing competition shoes for elite athletes| News". www.worldathletics.org. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- The Race for Brands to Match Nike’s Vaporfly, retrieved March 26, 2020

- "Nike Vaporfly Shoes Controversy". NPR.org. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- sportsEmailEmailBioBioFollowFollow, Adam Kilgore closeAdam KilgoreReporter covering national. "Nike's Vaporfly shoes changed running, and the track and field world is still sifting through the fallout". Washington Post. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- Zabarenko, Deborah (June 19, 2007). "Reuters report". Reuters. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- "Nike". ClimateCounts. Archived from the original on February 12, 2011. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- Archived May 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Wicked Local". April 29, 2008. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2008.

- Todd, L. A.; Sitthichok, T. P.; Mottus, K.; Mihlan, G.; Wing, S. (2008). "Health Survey of Workers Exposed to Mixed Solvent and Ergonomic Hazards in Footwear and Equipment Factory Workers in Thailand". Annals of Occupational Hygiene. 52 (3): 195–205. doi:10.1093/annhyg/men003. PMID 18344534.

- Todd, L. A.; Mottus, K.; Mihlan, G. J. (2008). "A Survey of Airborne and Skin Exposures to Chemicals in Footwear and Equipment Factories in Thailand". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. 5 (3): 169–181. doi:10.1080/15459620701853342. PMID 18213531.

- Nudd, Tim. "W+K Finds Its First Ads Ever, for Nike, on Dusty Old Tapes". Adweek. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- "Nike's Knight Is Advertiser of the Year". AllBusiness.com. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- Fass, Allison (August 31, 2000). "The Media Business – Advertising – Addenda – Nike Spot Wins An Emmy Award". New York Times. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- Rutenberg, Jim (September 20, 2002). "Nike Spot Wins An Emmy Award". The New York Times. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- According to a July 28, 1987 article written by the Associated Press.

- "Skateboarding". Nike. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- Brettman, Allan (June 22, 2011). "Nike courts controversy, publicity with drug-themed skater shirts". The Oregonian. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- "Nike Inc. (NYSE:NKE) Facing Slogan Backlash". stocksandshares.tv. June 24, 2011. Archived from the original on June 27, 2011.

- "Nike Signs 8-Year Deal With NBA". BallerStatus.com. June 11, 2015.

- Dator, James (June 26, 2017). "The Hornets will be the only NBA team to have jerseys licensed by Jumpman". SB Nation. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- Meyer, Jack (August 14, 2019). "History of Nike: Timeline and Facts". TheStreet.com. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

- "Fire on the Track - The Steve Prefontaine Story - Part 1". YouTube. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- Skidmore, Sarah. "23 years later, Air Jordans maintain mystique", The Seattle Times, January 10, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- Bailey, Ryan. "The 10 Most 'Bling' Boots in Football". Bleacher Report. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- "A Shortish History of Online Video". Vidyard. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- "Paterno's name off child care center". FOX Sports. July 12, 2012. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- "Joe Paterno's Name Removed From Child Development Center at Nike Headquarters". NESN.com. July 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- "Jogadores de Futebol Patrocinados pela Nike". Nike Brasil. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- "Nike offers further backing for Asian soccer". Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- "Premier League: Sportswear giants Nike to end Manchester United sponsorship". Sky Sports. London. August 7, 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- "Manchester United sign record 10-year kit deal with Adidas worth £750m". Sky Sports. London. July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- "LFC announces multi-year partnership with Nike as official kit supplier from 2020-21". Liverpool F.C. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- https://news.nike.com/news/the-history-of-nike-tennis

- Handley, Lucy (April 6, 2018). "Nike welcomes Tiger Woods back to the Masters with ad featuring his greatest hits". www.cnbc.com. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- Tom Fordyce (January 14, 2013). "Rory McIlroy, Nike and the $250m, 10-year sponsorship deal". BBC. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- "Team India's new NIKE ODI kit". Cricbuzz.com. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- "Indian Cricket team's NIKE ODI kit". Cricketliveguide.com. September 29, 2010. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- Scott, Roxanna (February 21, 2013). "Oscar Pistorius dropped by Nike". USA Today. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- "Sources: NBA, Nike have near-$1B apparel deal". ESPN.com. June 10, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- Fleetwood, Nicole R. (2015). On Racial Icons: Blackness and the Public Imagination (DGO - Digital original ed.). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6515-6.

- "Nike Zoom Kobe 4 Protro 'White/Del Sol' POP Returns May 24 On SNKRS". Lakers Nation. May 23, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- "Vince Carter Nike Shox BB4 Raptors PE | SneakerNews.com". Sneaker News. March 7, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- "Nike Unleashes "Hot Lava" LeBron 16s". HYPEBEAST. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- "Kevin Durant unveils Nike KD 12". SI.com. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- "The story behind Paul George's signature sneaker". SI.com. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- "Nike stocks fall after basketball prodigy touted as the 'next LeBron James' blows out his sneaker". nine.come. au. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- Alger, Tyson. "Oregon Ducks add orange to their Nike uniform repertoire for Colorado game". The Oregonian. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- Peter, Josh. "Behind Oregon's (Phil) Knight in shining armor". USA Today. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- Germano, Sara. "Nike Pledges $13.5 Million to Help Renovate University of Oregon Track Facilities". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- Bishop, Greg. "Oregon Embraces 'University of Nike' Image". The New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- "(RED) Partners". (RED). (RED), a division of The ONE Campaign. 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- "Nike Community Ambassadors | Nike Global Community Impact". Nike Global Community Impact. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

Further reading

- "The Swoon of the Swoosh" by Timothy Egan at The New York Times Magazine, September 13, 1998

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nike, Inc.. |

- Business data for Nike, Inc.:

- Company summary, from the New York Stock Exchange website