New Idria Mercury Mine

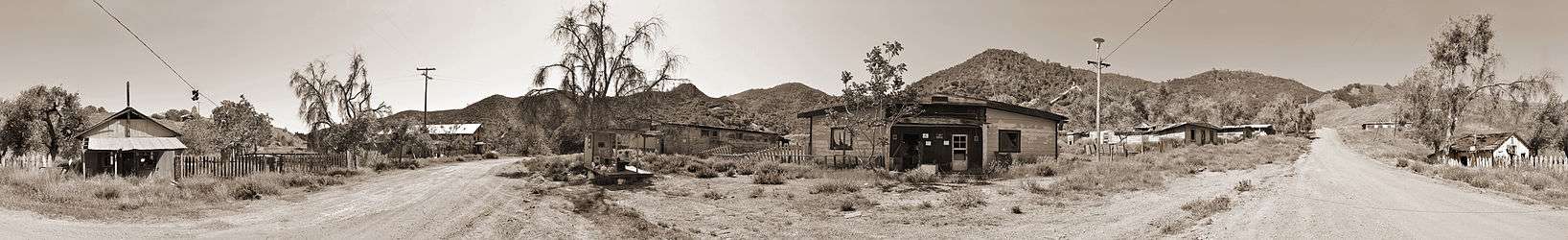

The New Idria Mercury Mine encompasses 8,000 acres of land in the Diablo Mountain range, incorporating the town of Idria in San Benito County, California. Idria, initially named New Idria, is situated at 36°25′01″N 120°40′24″W and 2440 feet (680m) above mean sea level. The area was, in the past, recorded in the US Census Bureau as a rural community; however, Idria has become a ghost town since the closing of once lucrative mining operations in the early 1970s.[2]

New Idria | |

|---|---|

Quicksilver Mine | |

Pollution left behind | |

New Idria Location within the state of California | |

| Coordinates: 36°25′1″N 120°40′24″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | San Benito County |

| EPA code | CA0001900463 |

| Official name | New Idria Mine[1] |

| Reference no. | 324 |

In 1990, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) investigated the mercury contamination level in soils, groundwater, surface water, and air of Idria, and concerned with the impact that the mining industry had had on the local environment. However, the contamination was not ranked high enough to be listed on the EPA’s Superfund Site List, nor its National Priorities List.[3]

On March 10, 2011, after the site had been reassessed in 2002 along with an expanded site in 2009, the EPA finally proposed adding Idria to California's Superfund List. Mercury, along with heavy metals and acid mine drainage, were found in nearby San Carlos Creek, Silver Creek and a portion of Panoche Creek at high toxic level to aquatic organisms and nearby populations. The contamination was also shown to be potentially threatening to habitats extending to the San Joaquin River and San Francisco Bay.[4]

History

The New Idria Mercury Mine was claimed in 1854, with the first brick furnace built in 1857. During the California Gold Rush, mercury was the key component to extract Gold from ores. Mercury, a major component in the cinnabar-rich rocks in Idria, could be economically extracted to support nearby gold mining and processing operations. Idria eventually became the second most productive mercury mine in North America, producing over 38 million pounds of mercury during its lifetime. Mercury mining operations ceased in 1972, with the closure of the New Idria Quicksilver Mining Company.,[3][4] However, the environmental consequences of mercury mining remained well past the abandonment of the town.

Geology

The New Idria Serpentine is a elongate intrusive body, 14 miles long and 4 miles wide, surrounded by numerous former quicksilver mines. The Jurassic Franciscan Formation, consisting of arkosic sandstone, forms a discontinuous ring around this serpentine, or as inclusions. This New Idria dome is exposed at the crest of the Coalinga anticline. The New Idria thrust fault is located along the northeast portion of this core, though normal faults are located along the southwest and west boundary. The New Idria Serpentine is the source of the quicksilver mineralization, and chrysotile asbestos. Bordering this plug of rocks is the Upper Cretaceous Panoche Formation consisting of silty-shale and concretionary sandstone up to 20,000 feet thick. Most of the New Idria mine production came from the hydrothermally altered shale controlled by faulting. Quicksilver deposits also occur in silica-carbonate rocks produced from serpentine, known as the "Quicksilver Rock" of California. Cinnabar is the chief ore mineral.[5]

Regional Mercury Reservoir

The land surrounding New Idria Mercury Mine currently has an emissions flux of 9.2 ng Hg/m2h, possibly lower than expected due to the amount of mercury confined to rock fractures and unit boundaries. The annual flux is around 18 kg per year. Since Idria has natural mercury reservoirs, it is important to factor in these background emissions in measuring the total impact from mining itself. As such, areas disrupted by human activity have been measured to contribute around 15% of these total (background included) mercury emissions into the atmosphere.[6]

Once abandoned, the New Idria Mercury Mine also discharged mercury-containing acid mine drainage (AMD) into San Carlos Creek, Silver Creek and a portion of Panoche Creek. AMD discharge accounted for about 50% of the water downstream from the mine and heavily impacted downstream ecosystems. It's estimated that AMD inputs into the surface water was 24 L/s during the six months of wet season and 5 L/s during the six months of dry season, with downstream unfiltered total mercury concentrations of 3400 ng/L (measured in 1997). 1500 g of mercury have been released from the mine each year.,[7][8]

Mercury Speciation in New Idria

Three main sources of mercury are industrial discharge, atmospheric deposition, and discharge from inoperative gold and mercury mines. Idria, as well as the western United States as a whole, faces a sizable threat of mercury contamination from the latter due to the prevalence of such mining operations.,[3][7]

Mercury, known to be highly toxic, has been found in various forms in Idria: elemental mercury (Hg(0)), inorganic mercury (Hg(II)) and monomethyl mercury(CH3Hg+, also called MMHg). MMHg, a potent neurotoxin, poses the greatest threat to organisms.[7] Measurements were taken by collecting water samples, which were later analyzed by tin chloride reduction, atomic fluorescence, and cold vapor atomic fluorescence spectrometry. The samples showed that mercury discharge and interaction was occurring throughout the course of the San Carlos Creek. The biggest contributions were found in the acid mine drainage and the mine tailings 1.2 km downstream from the drainage input.[9]

However, mercury was not simply detected in steady increments; in some areas, there was mercury scavenging of unfiltered total mercury. Dissolved mercury also underwent abiotic atmospheric evasion as gaseous mercury was released into the atmosphere. Both processes accounted for the loss of measured mercury concentrations downstream.[7]

Effects and Consequences

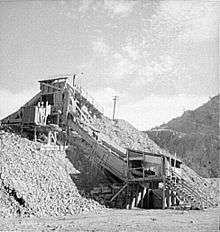

New Idria utilized the process of calcination to mine mercury, which involved crushing and roasting cinnabar, then condensing the release of mercury vapor.[10] The leftover ores or calcines from this process were piled along with other waste rock, totaling between 0.5 and 2 million tons and cover over 40 acres of mining ground.[4]

After the end of production in the 1970s, groundwater eventually flooded the mine and reacted with high iron and sulfur content of the bedrock. This created the ubiquitous acid mine drainage and acidic solution in New Idria, which was contaminated and allowed to run into the San Carlos Creek. The issue was compounded by the proximity of 2,500 feet of the creek’s flow to the calcine tailing piles, contaminating the water with mercury and other metals including aluminum, arsenic, copper, iron, and zinc[3]

Although there are few regularly occupied developments near the mine, there is a significant ecological concern associated with the uncontrolled drainage.[4] A small concentration of mercury can harm aquatic organisms, poison water streams and surrounding ecosystems in highly contaminated areas like Idria.[7] Waters enriched in mercury were detected as far as 20 miles downstream from the mine in Panoche Creek, at levels toxic to aquatic life.[10] The lengths of San Carlos, Silver, and Panoche Creek run through a regionally unique wetland habitat housing several threatened and endangered species, including the California red-legged frog and the steelhead trout.[11] The river system eventually flows into the San Joaquin River, and, subsequently, San Francisco Bay, areas of both recreational and commercial fishing.

Cleanup

The proposal to add the New Idria Mercury Mine to the Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund List was made in March 2011. EPA worked to re-rout the acid mine drainage out of the way of the waste pilings, construct a settling pool for the AMD, and minimize the erosion of the pilings into San Carlos Creek. These actions were completed in November 2011, with follow-up investigations scheduled for late 2013.[12]

See also

Notes

- "New Idria Mine". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-10-11.

- New Idria, California

- http://www.new-idria.org/

- http://yosemite.epa.gov/R9/SFUND/R9SFDOCW.NSF/3dc283e6c5d6056f88257426007417a2/54dc8315ad9b2118882578640082622e/$FILE/NIMM3_11_294kb.pdf

- Linn, Robert (1968). Ridge, John (ed.). New Idria Mining District, in Ore deposits of the United States, 1933-1967. New York: The American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers, Inc. pp. 1623–1649.

- Gustin, Mae Sexauer. "Are mercury emissions from geologic sources significant? A status report." Science of the Total Environment 304.1 (2003): 153-167

- Ganguli, Priya M., et al. "Mercury speciation in drainage from the New Idria mercury mine, California." Environmental science & technology 34.22 (2000): 4773-4779

- Gustin, Mae Sexauer, et al. "Assessing the contribution of natural sources to regional atmospheric mercury budgets." Science of the Total Environment259.1 (2000): 61-71.

- Ganguli, Priya M. Mercury speciation in acid mine drainage: New Idria Quicksilver Mine, California. Diss. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, 1998

- http://yosemite.epa.gov/R9/SFUND/R9SFDOCW.NSF/3dec8ba3252368428825742600743733/4d99072d0c3ba0ce8825784f00067c90!OpenDocument

- http://www.cdpr.ca.gov/docs/endspec/espdfs/35pe1299.pdf

- http://cfpub.epa.gov/supercpad/cursites/csitinfo.cfm?id=0905346

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New Idria. |