Nectocaris

Nectocaris pteryx is a species of possible cephalopod[2] known from the "early Cambrian" (Series 2) Emu Bay Shale and Chengjiang biota, the "middle Cambrian" (Mioalingian, Wuliuan) Burgess Shale.

| Nectocaris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Current reconstruction showing the large and small morphs of Nectocaris (from Smith, 2013[1]) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca (?) |

| Family: | †Nectocarididae |

| Genus: | †Nectocaris Conway Morris, 1976 |

| Species: | †N. pteryx |

| Binomial name | |

| †Nectocaris pteryx Conway Morris, 1976 | |

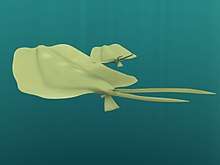

Nectocaris was a free-swimming, predatory or scavenging organism. This lifestyle is reflected in its binomial name: Nectocaris means "swimming shrimp" (from the Ancient Greek νηκτόν, nekton, meaning "swimmer" and καρίς, karis, "shrimp"; πτέρυξ, pteryx, means "wing"). Two morphs are known: a small morph, about an inch long, and a large morph, anatomically identical but around four times longer.[3]

The closely related Ordovician taxon Nectocotis is a second genus, closely resembling Nectocaris, but possessing an internal skeletal element.[4]

Anatomy

Nectocaris had a flattened, kite-shaped body with a fleshy fin running along the length of each side.[2] The small head had two stalked eyes, a single pair of tentacles, and a flexible funnel opening out to the underside of the body.[2] The funnel often gets wider away from the head. Internally, a chamber runs along the body axis, containing a pair of gills; the gills comprise blades emerging from a zig-zag axis. Muscle blocks surrounded the axial cavity, and are now preserved as dark blocks in the lateral body.[3] The fins also show dark blocks, with fine striations superimposed over them. These striations often stand in high relief above the rock surface itself.[3]

Diversity

Although Nectocaris is known from Canada, China and Australia, in rocks spanning some 20 million years, there does not seem to be much diversity; size excepted, all specimens are anatomically very similar. Historically, three genera have been erected for nectocaridid taxa from different localities, but these 'species' – Petalilium latus and Vetustovermis planus – likely belong to the same genus or even the same species as N. pteryx. Within N. pteryx, there seem to be two discrete morphs, one large (~10 cm in length), one small (~3 cm long). These perhaps represent separate male and female forms.[3]

Ecology

The unusual shape of the nectocaridid funnel has led to its interpretation as an eversible proboscis, but this is difficult to reconcile with the fossil evidence. Instead, its fluid dynamics seem optimal for a role in jet propulsion, where it would have maintained an efficient slow flow of water over the large internal gills.[3] The eyes of Nectocaris would have had a similar visual acuity to modern Nautilus (if they lacked a lens) or squid (if they did not).[3]

Affinity

The affinity of Nectocaris has been a controversial subject, and some scientists feel that it is still uncertain.[5][6] The balance of evidence seems to suggest a relationship with the cephalopods, whether in an ancestral or derived position.[3] The most pleasing interpretation – which is not without problems – is to interpret some of the features of Nectocaris as shared with the earliest cephalopods. Features that seem to be shared with the modern coleoids (which evolved much later) can then be attributed to convergence – but perhaps using the same underlying genetic machinery as modern coleoids do today.[3]

History of study

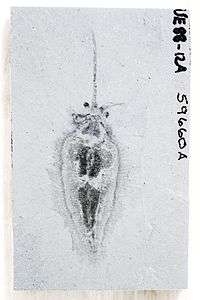

Nectocaris has a long and convoluted history of study. Charles Doolittle Walcott, the discoverer of the Burgess Shale, had photographed the one specimen he had collected in the 1910s, but never had time to investigate it further. As such, it was not until 1976 that Nectocaris was formally described, by Simon Conway Morris.[7]

Because the genus was originally known from a single, incomplete specimen and with no counterpart,[8] Conway Morris was unable to deduce its affinity. It had some features which were reminiscent of arthropods, but these could well have been convergently derived.[7][9] Its fins were very unlike those of arthropods.[7]

Working from photographs, the Italian palaeontologist Alberto Simonetta believed he could classify Nectocaris within the chordates.[10] He focussed mainly on the tail and fin morphology, interpreting Conway Morris's 'gut' as a notochord – a distinctive chordate feature.[10]

The classification of Nectocaris was revisited in 2010, when Martin Smith and Jean-Bernard Caron described 91 additional specimens, many of them better preserved than the type. These allowed them to reinterpret Nectocaris as a primitive cephalopod, with only 2 tentacles instead of the 8 or 10 limbs of modern cephalopods. The structure previous researchers had identified as an oval carapace or shield behind the eyes[11] was suggested to be a soft funnel, similar to the ones used for propulsion by modern cephalopods. The interpretation would push back the origin of cephalopods by at least 30 million years, much closer to the first appearance of complex animals, in the Cambrian explosion, and implied that – against the widespread expectation – cephalopods evolved from non-mineralized ancestors.[2]

A later analysis claimed to undermine the cephalopod interpretation, stating that it did not square with the established theory of cephalopod evolution.[12] According to these authors, Nectocaris is best treated as a member incertae sedis of the arthropod group Dinocaridida (which includes the anomalocaridids), but they stopped short of formally changing the classification.[12] However, it is straightforward to demonstrate that an anomalocaridid affinity is not supported.[5][13] Other studies have yet to put forward a more plausible affinity,[5][6] and alternatives to the cephalopod affinity are fraught with difficulties.[3] Whether Nectocaris represents a derived or basal cephalopod, and whether it belongs in the stem or crown group, it is more parsimonious to interpret its distinctive features as homologues of their equivalent in cephalopods – even if the absence of a shell in Nectocaris is an independent feature.[3]

Vetustovermis

Vetustovermis (from Latin: "very old worm")[14] is a soft-bodied middle Cambrian animal, known from a single reported fossil specimen from the South Australian Emu Bay shale. It is probably a junior synonym of Nectocaris pteryx.[3]

The original description of Vetustovermis hedged its bets regarding classification, but tentatively highlighted some similarities with the annelid worms.[14] It was later considered an arthropod,[15][16] and in 2010 Smith and Caron, agreeing that Petalilium was at least a close relative of Vetustovermis (but that treating it as a synonym was premature, given the poor preservation of the Vetustovermis type), placed it with Nectocaris in the clade Nectocarididae.[2]

Early press reports misspelled the genus name as Vetustodermis.

Petalilium

Petalilium (sometimes misspelled Petalium)[17] is an enigmatic genus of Cambrian organism known from the Haikou area,[18] from the Maoshoiatan mudstone member of the Chengjiang biota.[19] The taxon is a junior synonym of Nectocaris pteryx.[3]

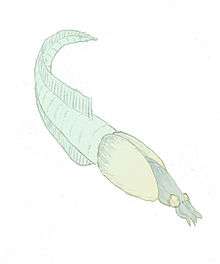

Fossils of Petalilium[lower-alpha 1] show a dorsoventrally flattened body, usually 5 to 6 centimetres, but ranging from 1.5 to 10 cm. It has an ovate trunk region and a large muscular foot, and a head with stalked eyes and a pair of long tentacles. The trunk region possesses about 50 soft, flexible, transverse bars, lateral serialised structures of unknown function. The upper part of the body, interpreted as a mantle, is covered with a random array of spines on the back, while gills project underneath. A complete, tubular gut runs the length of the body.

Whilst it was originally described as a phyllocarid,[15] and a ctenophore affinity has been suggested,[20] neither interpretation is supported by any compelling evidence.[21]

Some of the characters observed in Chen et al.'s (2005) study[17] suggested that Petalilium may be related to Nectocaris.[2]

See also

- Cambrian explosion

- Chengjiang biota

Footnotes

References

- Smith, M.R. (2013). "Data from: Affinity, ecology and diversity of the early 'cephalopod' Nectocaris". Dryad Digital Repository (dataset). Cambrian explosion. doi:10.5061/dryad.7m6kg. hdl:10255/dryad.46734.

- Smith, M.R.; Caron, J.B. (2010). "Primitive soft-bodied cephalopods from the Cambrian". Nature. 465 (7297): 469–472. Bibcode:2010Natur.465..469S. doi:10.1038/nature09068. hdl:1807/32368. PMID 20505727. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016.

- Smith, M.R. (2013). "Nectocaridid ecology, diversity and affinity: Early origin of a cephalopod-like body plan". Paleobiology. 39 (2): 291–321. doi:10.1666/12029.

- Smith, Martin R. (2019). "An Ordovician nectocaridid hints at an endocochleate origin of Cephalopoda" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 94: 64–69. doi:10.1017/jpa.2019.57b.

- Runnegar, B. (2011). "Once again: Is Nectocaris pteryx a stem-group cephalopod?". Lethaia. 44 (4): 373. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2011.00296.x.

- Kröger, B.R.; Vinther, J.; Fuchs, D. (2011). "Cephalopod origin and evolution: A congruent picture emerging from fossils, development and molecules". BioEssays. 33 (8): 602–613. doi:10.1002/bies.201100001. PMID 21681989.

- Conway Morris, S. (1976). "Nectocaris pteryx, a new organism from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Monatshefte. 12: 703–713.

- Gould, S.J. (1989). Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. Hutchison Radius. Bibcode:1989wlbs.book.....G. ISBN 978-0-09-174271-3.

- Waggoner, B.M. (1996). "Phylogenetic hypotheses of the relationships of Arthropods to Precambrian and Cambrian problematic fossil taxa". Systematic Biology. 45 (2): 190–222. doi:10.2307/2413615. JSTOR 2413615.

- Simonetta, A.M. (1988). "Is Nectocaris pteryx a chordate?". Bollettino di Zoologia. 55 (1–2): 63–68. doi:10.1080/11250008809386601.

- Conway Morris, Simon (1989). "Burgess Shale Faunas and the Cambrian Explosion". Science. 246 (4928): 339–346. Bibcode:1989Sci...246..339C. doi:10.1126/science.246.4928.339. PMID 17747916.

- Mazurek, D.; Zatoń, M. (2011). "Is Nectocaris pteryx a cephalopod?". Lethaia. 44: 2–4. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2010.00253.x.

- Smith, M.R.; Caron, J.-B. (2011). "Nectocaris and early cephalopod evolution: Reply to Mazurek & Zatoń". Lethaia. 44 (4): 369–372. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2011.00295.x.

- Glaessner, M.F. (1979). "Lower Cambrian Crustacea and annelid worms from Kangaroo Island, South Australia". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 3: 21–29. doi:10.1080/03115517908565437.

- Luo, H.-L.; Hu, S.-X.; Chen, L.-Z. (1999). Early Cambrian Chengjiang fauna from Kunming region, China. Kunming, China: Yunnan Science & Technology Press.

- "Strange fossil defies grouping". BBC News.

- Chen, J.Y.; Huang, D.Y.; Bottjer, D.J. (2005). "An Early Cambrian problematic fossil: Vetustovermis and its possible affinities". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 272 (1576): 2003–2007. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3159. PMC 1559895. PMID 16191609.

- Steiner, M.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Erdtmann, B. (2005). "Lower Cambrian Burgess Shale-type fossil associations of South China". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 220 (1–2): 129–152. Bibcode:2005PPP...220..129S. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2003.06.001.

- Han, J.; Shu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Yao, Y. (2006). "Preliminary notes on soft-bodied fossil concentrations from the Early Cambrian Chengjiang deposits". Chinese Science Bulletin. 51 (20): 2482. Bibcode:2006ChSBu..51.2482H. doi:10.1007/s11434-005-2151-0.

- Chen, L.Z.; Luo, H.L.; Hu, S.X.; Yin, J.Y.; Jiang, Z.W.; Wu, Z.L.; Li, F.; Chen, A.L. (2002). Early Cambrian Chengjiang Fauna in Eastern Yunnan, China (in Chinese and English). Kunming: Yunnan Science and Technology Press. p. 199.

- Hu, S.; Steiner, M.; Zhu, M.; Erdtmann, B.D.; Luo, H.; Chen, L.; Weber, B. (2007). "Diverse pelagic predators from the Chengjiang Lagerstätte and the establishment of modern-style pelagic ecosystems in the early Cambrian". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 254 (1–2): 307–316. Bibcode:2007PPP...254..307H. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.03.044.

Further reading

- "Nectocaris pteryx". Burgess Shale Fossil Gallery. Virtual Museum of Canada. 2011. – 3D animations are available and a more detailed consideration of Nectocaris

- Switek, Brian (5 July 2011). "Nectocaris: What the heck is this thing?". Laelaps. – Brian Switek discusses the taxonomy and history of Nectocaris in his blog

- Moskvitch, Katia (27 May 2010). "Mystery fossil is ancestor of squid". BBC News. – BBC News coverage of the Smith & Caron's (2010) re-description

- Taylor, Christopher (14 January 2011). "So nice when people agree with you". Catalogue of Organisms. – a blog article supporting Mazurek & Zatoń's (2011) view

- Conway Morris, S. (1997). The Crucible of Creation: the Burgess Shale and the rise of animals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-286202-2.

External links