Nausicaa

Nausicaa (/nɔːˈsɪkiə/, also US: /-keɪə, naʊˈ-/;[1][2] Ancient Greek: Ναυσικάα, romanized: Nausikáa, or Ναυσικᾶ, Nausikâ [nau̯sikâː]) also spelled Nausicaä or Nausikaa, is a character in Homer's Odyssey. She is the daughter of King Alcinous and Queen Arete of Phaeacia. Her name means "burner of ships" (ναῦς ‘ship’; κάω ‘to burn’).[3]

Role in the Odyssey

In Book Six of the Odyssey, Odysseus is shipwrecked on the coast of the island of Scheria (Phaeacia in some translations). Nausicaä and her handmaidens go to the seashore to wash clothes. Awakened by their games, Odysseus emerges from the forest completely naked, scaring the servants away, and begs Nausicaä for aid. She gives Odysseus some of the laundry to wear and takes him to the edge of the town. Realizing that rumors might arise if Odysseus is seen with her, she and the servants go into town ahead of him, but first she advises him to go directly to Alcinous's house and make his case to Nausicaä's mother, Arete. Arete is known as wiser even than Alcinous, and Alcinous trusts her judgment. Odysseus follows this advice, approaching Arete and winning her approval, and is received as a guest by Alcinous.[4]

During his stay, Odysseus recounts his adventures to Alcinous and his court. This recounting forms a substantial portion of the Odyssey. Alcinous then generously provides Odysseus with the ships that finally bring him home to Ithaca.

Nausicaä is young and very pretty; Odysseus says she resembles a goddess, particularly Artemis. Nausicaä is known to have several brothers. According to Aristotle and Dictys of Crete, she later married Odysseus's son Telemachus, and had a son, Poliporthes.

Homer gives a literary account of love never expressed (possibly one of the earliest examples of unrequited love in literature). Nausicaä is presented as a potential love interest for Odysseus: she tells her friend that she would like her husband to be like him, and her father tells Odysseus that he would let him marry her. But the two do not have a romantic relationship. Nausicaä is also a mother figure for Odysseus; she ensures his return home, and says "Never forget me, for I gave you life". Odysseus never tells Penelope about his encounter with Nausicaä, out of all the women he met on his long journey home. Some suggest this indicates a deeper level of feeling for the young woman.[5]

Later influence

- The 2nd century BC grammarian Agallis attributed the invention of ballgames to Nausicaä, most likely because she was the first person in literature to be described playing with a ball.[6] (Herodotus 1.94 attributes the invention of games, including ballgames, to the Lydians.)

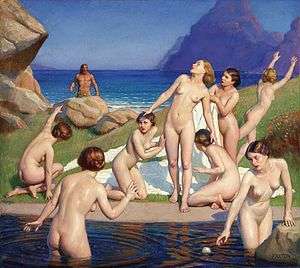

Odysseus and Nausicaä, by William McGregor Paxton

Odysseus and Nausicaä, by William McGregor Paxton

- An asteroid discovered in the year 1879, 192 Nausikaa, is named after her.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, in Beyond Good and Evil, said: "One should part from life as Odysseus parted from Nausicaa—blessing it rather than in love with it."

- In his 1892 lecture "The Humor of Homer" (collected in his Selected Essays), Samuel Butler concludes that Nausicaä was the real author of the Odyssey, since the laundry scene is more realistic and plausible than many other scenes in the epic. His theory that the Odyssey was written by a woman was further developed in his 1897 book The Authoress of the Odyssey.

- An episode in James Joyce's Ulysses echoes the Nausicaä story to a degree: the character Gerty McDowell (Nausicaä's analogue) tempts Bloom.

- In 1907, the Hungarian composer Zoltán Kodály wrote the song "Nausikaa" to a poem by Aranka Bálint. Kodály showed great interest in Greek antiquity in his whole life, studying the language thoroughly and reading up on different editions of the Iliad and Odyssey, and began planning an opera about Odysseus in 1906. Only one song, "Nausikaa", survived from this plan.

- In 1915 the Polish composer Karol Szymanowski completed Métopes, op. 29, a cycle of three miniature tone poems drawing on Greek mythology and each featuring a female character Odysseus encounters on his homeward voyage. The movements are "The Isle of the Sirens", "Calypso" and "Nausicaa".

- William Faulkner named the cruise ship Nausikaa in his 1927 novel Mosquitoes.

- Armenian poet, prose writer Yeghishe Charents wrote his poem "Navzike" in 1936 about longing for his Nausicaä, himself being "lost" in the political storms of the forties.[7]

- Robert Graves's 1955 novel Homer's Daughter presents Nausicaä as the Odyssey's author.

- The Australian composer Peggy Glanville-Hicks wrote the opera Nausicaa (libretto by Graves), first performed in 1961 at the Athens Festival.

- The poet Derek Walcott's poem "Sea Grapes" alludes to Nausicaa.[8]

- On film, Nausicaa was portrayed by Rossana Podestà in the 1954 film Ulysses, by Barbara Bach in the Ialian 1968 miniseries L'Odissea, and by Katie Carr in the 1997 miniseries The Odyssey.

- The title character of the 1982 manga Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and its 1984 animated film adaptation, written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki, was indirectly inspired by the Odyssey. Miyazaki read a description of Nausicaa in a Japanese translation of Bernard Evslin's anthology of Greek mythology, which portrayed her as a lover of nature. He added other elements based on Japanese short stories and animist tradition.

- In 1991, the public aquarium Nausicaä Centre National de la Mer, one of Europe's largest, opened in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France.

- In 2010, the band Glass Wave recorded the song "Nausicaa", written from her point of view.

- Nausicaans are a race of tall, strong, aggressive humanoids in the Star Trek universe.

References

- "Nausicaa". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- "Nausicaä". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Shipley, Joseph T. (2011). The Origins of English Words: A Discursive Dictionary of Indo-European Roots. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 160.

- Hamilton, Edith (1999) [1942]. Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes. New York: Grand Central Publishing Hachette Book Group USA.

- Powell, Barry B. Classical Myth. Second ed. With new translations of ancient texts by Herbert M. Howe. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1998, p. 581.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. (1990). Women in Hellenistic Egypt: From Alexander to Cleopatra. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-8143-2230-1.

- "Charents Yeghishe - armenianlanguage.am". www.armenianlanguage.am.

- Derek Walcott, "Sea Grapes," Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

Sources

- Portions of this material originated as excerpts from the public-domain 1848 edition of the Classical Dictionary by John Lemprière.

External links