Nausicaä (character)

Nausicaä (/ˈnɔːsɪkə/; Naushika (ナウシカ, [naɯꜜɕi̥ka])) is a fictional character from Hayao Miyazaki's science fiction manga series Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and his anime film of the same name. Her story is set in the future on a post-apocalyptic Earth, where Nausicaä is the princess of the Valley of the Wind, a minor kingdom. She assumes the responsibilities of her ill father and succeeds him to the throne over the course of the story. Fueled by her love for others and for life itself, Nausicaä studies the ecology of her world to understand the Sea of Corruption, a system of flora and fauna which came into being after the Seven Days of Fire.

| Nausicaä | |

|---|---|

| Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind character | |

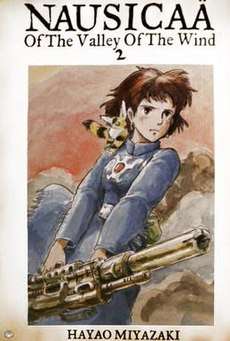

Nausicaä on the cover of volume 2 of the Viz "Editor's Choice" manga release. Teto is on her shoulder. | |

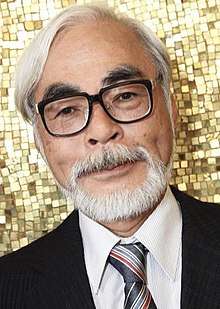

| Created by | Hayao Miyazaki |

| Voiced by | Sumi Shimamoto |

| In-universe information | |

| Relatives | King Jihl (father) |

| Nationality | Valley of the Wind |

Nausicaä's abilities include determination and commitment. Her magnetic personality attracts admiration and adoration from nearly all those who meet her. Her empathy allows her to communicate with many animals. Nausicaä joins a war between adjacent territories of the remaining inhabitable land. Assuming command of the Valley's small force sets her off on a journey that will alter the course of human existence.

Many experts and manga enthusiasts have interpreted the character. Nausicaä won the seventh Animage Grand Prix,[1] and the June 1987 Grand Prix,[2] coming second in May 1991,[3] and again coming first in December 1992.[4] In 2014, IGN ranked her as the ninth greatest anime character of all time, saying that "She is a genuine, charismatic character who is loved and respected by her people. But she's also a capable, though reluctant, warrior."[5]

Character outline

Although a skillful fighter,[6] Miyazaki's Nausicaä is humane and peace-loving. She has an unusual gift for communicating with the giant insects and is noted for her empathy toward animals, humans, as well as other beings. As an intelligent girl, Nausicaä frequently explores the toxic wasteland, which surrounds the realms and conducts scientific experiments in an attempt to define the true nature and origins of the toxic world in which she lives. Her explorations are facilitated by her skill at "windriding": flying with an advanced glider-like craft called Mehve, equipped with a jet-assist.

Development

Nausicaä has her origins in Miyazaki's aborted anime adaption of Richard Corben's Rowlf, a comic book about princess Maryara of the Land of Canis and her dog Rowlf.[7] Miyazaki found similarities with Beauty and the Beast. The similarities inspired in him the desire to create a character to highlight the theme of "devotion, self-giving".[lower-alpha 1] Finding Corben's princess "bland", Miyazaki imagined "a young girl with character, brimming with sensitivity, to contrast her with an incapable father".[lower-alpha 2] Named "Yara" (ヤラ, yara) by Miyazaki, short for Corben's Maryara, this character was a young princess left "bearing the crushing weight of her destiny" when her sick father abdicated, bestowing the burden of the kingdom on her and forcing her to bridle her personal aspirations.[lower-alpha 3] Miyazaki's Yara is initially portrayed with a dog "which always accompanied her from a young age and especially cared for his mistress". This pet dog is found in many design sketches of Yara but is omitted when the story develops. Canis valley eventually becomes Valley of the Wind and the pet dog is replaced with a fictional fox squirrel. Miyazaki intended Yara to wear short pants and moccasins, exposing her bare legs "to effectively show vigorous movements and a dynamic character", but he had to abandon that idea as it did not make sense to expose her legs in the harsh environment that began to evolve as he developed the setting for the story. [lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5]

The transition from Yara to Nausicaä came when Miyazaki began to develop his own character, after the project to adapt Corben's comic fell through. The character went through a few intermediate phases in which the name was retained. Miyazaki had taken a liking to the name "Nausicaä" and he used it to rename his main character.

The name comes from the Phaeacian princess Nausicaa of the Odyssey, who assisted Odysseus. The Nausicaa of the Odyssey was "renowned for her love of nature and music, her fervid imagination and disregard for material possessions", traits which Dani Cavallaro sees in Miyazaki's Nausicaä.[12] Miyazaki has written that he identified particularly with Bernard Evslin's description of the character in Gods, Demigods and Demons, translated into Japanese by Minoru Kobayashi.[lower-alpha 6] Miyazaki expressed disappointment, about not finding the same splendor in the character he had found in Evlin's book, when he read Homer's original poem.[lower-alpha 7]

Another inspiration is the main character from The Princess Who Loved Insects, a Japanese tale from the Heian period, one of the short stories collected in the Tsutsumi Chūnagon Monogatari. It tells the story of a young princess who is considered to be rather eccentric by her peers because, although of marriageable age, she prefers to spend her time outdoors studying insects, rather than grooming herself in accordance with the rules and expectations of the society of her era. The princess questions why other people see only the beauty of the butterfly and do not recognise the beauty and usefulness of the caterpillar from which it must grow.[19] Miyazaki notes that the lady would not be perceived the same way in our own time as in the Heian period. He wonders about her ultimate fate, which isn't explained in the surviving fragments of the incomplete texts. Miyazaki has said that Evslin's Nausicaa reminds him of this princess, stating that the two characters "became fused into one and created the story".[lower-alpha 8]

Miyazaki also said that Nausicaä is "governed by a kind of animism".[20] Miyazaki felt that it was important to make Nausicaä a female because he felt that this allowed him to create more complex villains, saying, "If we try to make an adventure story with a male lead, we have no choice but to do Indiana Jones, with a Nazi or someone else who is a villain in everyone's eyes." Miyazaki said of Nausicaä that "[She] is not a protagonist who defeats an opponent, but a protagonist who understands, or accepts. She is someone who lives in a different dimension. That kind of person should be female, not male."[21] When asked about Nausicaä's "vision and intellect far greater than other people's," her "distinguished fighting skills," as well as her leadership, including taking "the role of legendary savior," Miyazaki said that he wanted to create a heroine who was not a "consummately normal" person, "just like you or everyone else around you."[22]

Nausicaä's affinity with the wind was inspired by translations of European geography books from the Middle Ages, where mastery of the wind was described as "witchcraft" and was feared and respected. Mills were described in these books as being used for "pushing sand dunes or grinding grain," which left an impression on Miyazaki. Inspired by the Earthsea cycle of Ursula K. Le Guin, Miyazaki coined the term kaze tsukai (風使い) as an alternative to Guin's "Master Windkey", which was translated into Japanese as kaze no shi (風の司, lit. "one who controls the wind").[lower-alpha 9]

Miyazaki had intended to make Yara more pulpy than his other female characters, a feature of sketches of her created between 1980 and 1982.[lower-alpha 10] However, he realised that he could not draw Nausicaä nude without feeling like he should apologise, changing his idea of the story to be more "spiritual."[22] When Miyazaki draws Nausicaä in poses which are a little "sexy", like the cover of Animage in March 1993, where Nausicaä smiles while wearing a torn tank top, he cautions that "Nausicaä never takes such a pose," however this does not prevent him from drawing her like this,[lower-alpha 11] saying, "Well, if I hadn't drawn her as beautiful, there would have been some problems. I thought that I should settle down and draw her consistently, but every time I drew her, her face changed-even I was overpowered."[22] He felt that over the 14-year run of the manga, rather than Nausicaä changing as a character, instead Miyazaki felt that he understood her better.[22] When Miyazaki is obligated to draw Nausicaä smiling for covers or character posters, he finds it difficult because "it does not match the character of [my] heroine."[lower-alpha 12] He does not like "representing Nausicaä as too radiant or with the attitudes typical of a heroine," and imagines that instead of this, when she is alone, she has a "serious [...] calm and collected" (but "not surly") attitude.[lower-alpha 13] He regards her "sombre and reserved" nature to be offset by her femininity. Miyazaki believes that characters like this, "far from being fulfilled [...] are the most altruistic."[lower-alpha 14]

The kana Miyazaki chose to write Nausicaä's name in, ナウシカ (nauʃika), follows the spelling used by Kobayashi for the translations of Evslin's work. Miyazaki prefers it to other transcriptions of Nausicaä also in use, ノシカ (noʃika) and ノジカ (noʒika).[lower-alpha 15] In English, the Greek name is normally pronounced /nɔːˈsɪkeɪ.ə/, but in the soundtrack for the film it is /ˈnɔːsɪkə/.

Helen McCarthy considers Shuna from Journey of Shuna to be prototypical to Nausicaä,[23] and Dani Cavallaro feels Lana from Future Boy Conan and Clarisse of Castle of Cagliostro are also prototypical to Nausicaä.[12]

Plot overview

The story of the manga, refined by Miyazaki over 13 years between February 1982 and March 1994, was published in the magazine Animage and collected into seven volumes. It is much more complex than the story told by the film.

The film was developed in 1983, when Tokuma Shoten, the publisher of Animage, felt that the manga was successful enough to make "a gamble" at a film being economically viable.[24] The film takes the context and characters, but the scenario is radically different from that of the manga,[25] although many scenes from the manga (corresponding roughly to the first two volumes) were used with only slight changes.

In the summary below, parts of the manga where Nausicaä is absent have been omitted to focus on the character.

In the manga

Nausicaä is the princess of the Valley of the Wind, a very small nation with fewer than 500 inhabitants (and steadily declining in population).[26] She is the eleventh child of King Jihl and the only one to live to maturity. She is rarely seen without her Mehve or her companion, Teto the fox-squirrel. At the beginning of the manga, Nausicaä, the princess of the Valley of the Wind, is set to succeed her ill father, who can no longer go to war to honour an old alliance. Under the command of the princess of Tolmekia, Kushana, Nausicaä needs to go to war against the Dorok Empire in a suicide mission across the Sea of Corruption.[lower-alpha 16] Delayed in the forest by the attack of Asbel, where she saves the insects, she encounters a tribe of Dorok and learns of their plans to destroy the Tolmekian army. She helps the baby Ohmu which was tortured by the Dorok to attract the insects to the Tolmekian army and her dress is stained blue with its blood. She is recognised as "The Blue Clad One", a figure in the Dorok mythos who is fated to cause a revolution in the world.

Having awakened the old heretical legends, Nausicaä becomes a mortal enemy of Miralupa, the younger of the two brothers who rule the Dorok Empire, who uses his mental powers to try to infiltrate her mind when she is weak. Miralupa is betrayed and murdered by his older brother, Namulith and at the doors of death, finds his redemption in the spirit of Nausicaä. Nausicaä discovers that the Dorok are using a new fungus of the forest as a biological weapon to extend their reach. She arrives at an understanding of the role of the Sea of Corruption and its inhabitants in the process of purifying the Earth.

When Namulith decided to forcefully marry Kushana to form a single empire under his rule she initially feigns acceptance but later rejects him and his proposal. His grand designs start to unravel. In a confrontation with Nausicaä, Namulith spitefully foists a rediscovered god-warrior off on Nausicaä in revenge and shoulders her with the burden of taking care of the reactivated creature and the responsibility for saving the world.[lower-alpha 17] The god-warrior is a living weapon, an artifact from the ancient world which led to the Seven Days of Fire. Not knowing what to do with this immeasurably dangerous and uncontrollable creature who takes her for its mother, found at Pejite, then stolen by the Tolmekians and finally by the Dorok, Nausicaä names the god-warrior Ohma. She decides to go with Ohma to the Crypt of Shuwa to seal all the technologies of the ancient world behind its doors. However, Ohma is damaged and crash lands near some ruins. Hidden within these ruins Nausicaä discovers the Garden of Shuwa, a repository of seeds, animals, as well as cultural knowledge from previous ages.

She goes through a test of character, as the Master of the Garden imitates her mother to tempt her to stay. She outwits the Master and learns the secrets of the Sea of Corruption and the Crypt. Meanwhile, Ohma, controlled by the Tolmekian Emperor Vuh, fights the Master of the Crypt. After cracking the crypt, Ohma dies of his wounds. Nausicaä finally joins in destroying the foundations of the building, sealing the old technology inside.

In the film

After finding the shell of an Ohmu while collecting spores in the Toxic Forest, Nausicaä rescues Master Yupa from an Ohmu that she pacifies. Lord Yupa gives Nausicaa a fox squirrel she names Teto. Upon returning to the Valley of the Wind, Obaba tells the legend of the Blue Clad One, who will walk in a field of gold and renew the lost link with the Earth. The next night, a Tolmekian airship is attacked by insects and crashes in the Valley of the Wind and Nausicaä hears the last words of Lastel, a princess of the city of Pejite who wants the ship's cargo to be destroyed. When the people of the Valley of the Wind try to destroy the airborne spores of the Toxic Jungle, they note that a wounded insect that Nausicaä reassured retreated back to the Toxic Jungle.

The cargo of the Tolmekian ship, a hibernating god-warrior, is retrieved by the people of the Valley of the Wind and they are immediately visited by many Tolmekian ships and tanks who kill Nausicaä's father King Jihl. The Tolmekians, led by Princess Kushana, intend to retrieve and awaken the god-warrior and use it to burn the Toxic Jungle. Obaba opposes this idea, saying that all who have tried to destroy the forest have been killed by the angry Ohmu and the jungle grew over their towns and bodies. However, to avoid a slaughter, Nausicaä agrees to become Kushana's hostage and accompany her to rejoin the main Tolmekian army at the city of Pejite, which the Tolmekians have already conquered.

During the journey, they are attacked by Lastel's brother Asbel, who almost destroys the entire fleet and is apparently killed. Mito, Nausicaä and Kushana escape using the gunship and land in the jungle. Nausicaä communicates with the Ohmu and discovers that Asbel is alive and she uses her glider to rescue him. They sink into the sands of the jungle and discover a non-toxic world beneath the jungle. Nausicaä realizes that the plants of the jungle are purifying the soil and producing clean water and air.

Actors

Nausicaä is voiced in Japanese by Sumi Shimamoto, who won the role after impressing Hayao Miyazaki with her performance of Clarisse in Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro.[lower-alpha 18] Patrick Drazen praised Shimamoto's acting in a scene where Nausicaä stops an insect from diving into an acidic pool by getting in its way. She is burned by the acid and she screams. Drazen described this scream as being one which "tears at the listener and raises the bar for cartoon voices".[24] In Walt Disney Pictures' English dub of the movie, Nausicaä's voice was performed by Alison Lohman.

Reception

In a chapter dealing with "Female masculinity and fantasy spaces", Nausicaä is described as being a "strong young female lead drawn strongly from the shoujo tradition", relating the story of a Takarazuka Revue playwright called Ogita who compares his work with Miyazaki's. For Ogita, it is most important that the heroines of Miyazaki are pure and asexual, to emphasise themes of purity and strength.[21] who "takes charge" of her own life,[6] Nausicaä has also been said to have a "brave and wholesome" mind,[29] and as "one of the best examples of a truly "empowered" female."[30] Stig Høgset found the too-perfect portrayal of Nausicaä to be unrealistic.[31] Susan J. Napier argues that as Nausicaa is the heroine of an epic, her competence, powers, and presentation as a messiah are not part of Nausicaa being an unrealistic character, but instead, she is real as a character inside the epic genre.[32] In the beginning of the film, Nausicaä is presented as "a mix of precocity and fairy-tale innocence", her innocence coming not from naivety but from scientific wonder.[33] Early in the story, she kills the warriors who killed her father, which Susan J. Napier described as "genuinely shocking,"[6] and Kaori Yoshida points to as evidence of Nausicaä representing "traditional masculinity rather than femininity".[29] When she avenges her father's death, the scene is "ambivalent" in its message, suggesting both "a masculine rite-of-passage" and "a moral object lesson", which makes Nausicaä afraid of her own power.[33] Nausicaä later "comes to regret her vengeance" and becomes a diplomat to prevent further wars between the different states.[34] Although Nausicaä is a warrior, Nausicaä acts "reassuringly cute" such as taming Teto and calling things "pretty", which contrasts her with San of Princess Mononoke.[6] Inaga Shimegi feels that Teto's taming is the first glimpse of Nausicaä's "supernatural ability of communication".[35] Thomas Zoth regards Nausicaä as "Miyazaki's archetypal heroine" and notes shades of her in Ashitaka, San and Lady Eboshi of Princess Mononoke.[34]

.jpg)

Opinion is divided as to whether Nausicaä is sexualised or not - Napier notes that Nausicaä's relationship with Asbel is "potentially erotic",[6] but Kaori Yoshida says that Nausicaä's body "is not the typical kind designed to stimulate" the male gaze.[29] The quality of tapes on early fansubs lead to the rumor that Nausicaä does not wear any pants.[36] Yoshida presents Hiromi Murase's theory that Nausicaä represents a post-oedipal mother figure.[29] Susan J. Napier and Patrick Drazen note a parallel between the character of Kushana, the rival warrior princess, and that of Nausicaä: Napier describes Kushana as Nausicaä's "shadow", noting that Kushana is not shown with any "alleviating, feminine" virtues as Nausicaä is, but that they share the same tactical brilliance.[37] Drazen describes this as a "feminine duality".[24] Miyazaki has described the two characters as being "two sides of the same coin", but Kushana has "deep, physical wounds".[22]

Nausicaä is presented as a messiah and also acts on an ideology of how to interact with the natural world. Her powers are presented as proof of the "rightness" of her "mode of thought". Unlike other characters who avoid or try to ignore the forest, Nausicaä is scientifically and beatifically interested in the forest. Lucy Wright believes that Nausicaa's world-view reflects a Shinto worldview, as expressed by Motoori Norinaga: "this heaven and earth and all things therein are without exception strange and marvelous when examined carefully." Wright believes that Nausicaa is presented as a "healing deity", as she is concerned with the space between purity and corruption, as well as atones for the wrongs of other people.[38] In the manga, Nausicaa faces an old monk who says "the death of the world is inescapable" because of the folly of men, Nausicaa retorts: "Our God of the Winds teaches us that life is above all! And I love life! The light, the sky, the men, the insects, I love them all more than anything!!"[39] Later, she responds to the Guardian of the tomb of Shuwa who tries to tell her she is selfish for refusing the purification program of the old Earth and allowing the sacrifice of all the lives of the ancient world: "We can know the beauty and the cruelty of the world without the help of a giant tomb and its retinue of servants. Because our god, he lives in the smallest leaf and the smallest insect."[40] Raphaël Colson and Gaël Régner see in these tirades a "world view which clearly calls to mind the spirit of Shinto".[41]

When the god soldier is activated, he chooses Nausicaä to be his "mother" and asks her who she wants him to kill. Marc Hairston considers this to be a recurring theme throughout the manga: Nausicaä is given power and is told to make difficult decisions.[42] In 2000, Nausicaä placed eleventh in an Animax poll of favourite anime characters.[43] The first daughter of Jean Giraud is named after the character.[44] The character Nakiami from Xam'd: Lost Memories has been noted to bear many similarities to Nausicaä.[45]

Frederik L. Schodt believes that in the film, Nausicaä's character became "slightly sweeter, almost sappy" and suggests that her "high voice" and the low camera angles which show the bottom of her skirt to be due to "an emphasis on 'prepubescent female cuteness' in commercial animation."[46] Marc Hairston reads the 1995 music video "On Your Mark" as being Miyazaki's "symbolic release" of Nausicaä.[47]

Raphaël Colson and Gaël Régner feel that Nausicaa had "to grow up faster than her age" because of her responsibilities, but that she acts with maturity, diplomacy, attention and resolve. They see her as "the princess of an idealised feudal system ... loved and respected by her subjects, ... feared and admired by her enemies."[48] The character Rey from the 2015 film Star Wars: The Force Awakens has been compared to Nausicaa, with both having generally similar personalities and strikingly similar headwear.[49]

Notes

- Recueil d'aquarelles: « la dévotion, le don de soi », Page 147.[8]

- Recueil d'aquarelles: « fade »... « une jeune fille au caractère affirmé, débordante de sensibilité et assortie d’un père incapable », Page 148.[8]

- Recueil d'aquarelles: « portant le poids écrasant de son destin », Page 148-149.[8] An example from the first volume; She has to go off to wage war on behalf of an allied kingdom, which means that she has to terminate her "secret garden", where she researches the plants from the Sea of Corruption. Animage Special 1, Page 82.[9]

- Recueil d'aquarelles: « qui l’accompagnait toujours depuis son plus jeune âge et qui éprouvait des sentiments particuliers envers sa maîtresse », Page 178-179, 188, 192-193.[8] July 1983 issue of Animage, page 164-165.[10] Kanō (2006), page 39.[11]

- Recueil d'aquarelles: « rendre efficacement les mouvements vigoureux d’un personnage dynamique », Page 193.[8]

- Mentioned as Minoru Kobayashi (小林稔, Kobayashi Minoru) in the Japanese Webcat Plus database and in Hayao Miyazaki's Watercolor Impressions. In the Japanese edition on page 150 and in the English edition on page 149.[13][14][15] On page 150 in the French translation of Watercolor Impressions book, and on some Nausicaä related websites, the translator's name is given as Yataka Kobayashi.[8]

- Hayao Miyazaki's essay On Nausicaä, ナウシカのこと (Naushika no koto) first published in Japanese in Animage Special 1, Endpaper.[9] Reprinted, in English translation, in Perfect Collection Volume 1.[16] See also McCarthy (1999), page 74.[17][18]

- On Nausicaa.[9][16]

- Recueil d'aquarelles: « repousser l’avancée des dunes ou moudre le grain », Page 150.[8]

- Recueil d'aquarelles, Page 178.[8]

- Recueil d'aquarelles: « Nausicaä ne prendrait jamais une telle pose », Page 68.[8]

- Recueil d'aquarelles: « ça ne correspond pas au caractère de [son] héroïne », Page 26.[8]

- Recueil d'aquarelles: « représenter Nausicaä trop rayonnante ou dans des attitudes typiques d’héroïne » ... « grave […] calme et posée » ... « pas renfrognée », Page 80.[8]

- Recueil d'aquarelles: « sombre et réservée ».... « loin d’être épanouis […] sont les plus altruistes », Page 152.[8]

- Recueil d'aquarelles, Page 150.[8]

- The mission, given by the brothers of Kushana, is a trap as they fear losing their sister.[27]

- Namulith is annoyed by Nausicaä's messianic side and her propensity to elevate people. She reminds him of Miralupa when he was briefly a philanthropist, about a century earlier. Quote:

"I will destroy your reputation and humiliate you. The warrior-god will return you to right. [...] Take all on your shoulders and see if you can save this world!" Based on the French translation of the manga: « Je briserai ta réputation et je t’humilierai. [...] Le dieu-guerrier te reviendra de droit […] Porte tout cela sur tes épaules, et voyons si tu peux sauver ce monde !!» [28] - McCarthy (1999), page 57.[17]

References

- "月刊アニメージュ【公式サイト】". Animage.jp. Archived from the original on May 23, 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- "月刊アニメージュ【公式サイト】". Animage.jp. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- "月刊アニメージュ【公式サイト】". Animage.jp. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- "月刊アニメージュ【公式サイト】". Animage.jp. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- Isler, Ramsey (February 4, 2014). "Top 25 Greatest Anime Characters". IGN. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- Napier, Susan J. (2001). "Confronting Master Narratives: History As Vision in Miyazaki Hayao's Cinema of De-assurance". Positions east asia cultures critique. 9 (2): 467–493. doi:10.1215/10679847-9-2-467. ISBN 9780822365204.

- Richard V. Corben (w, a). "Rowlf" Rowlf: 1/1 (1971), San Francisco: Rip Off Press, ISBN 9788436517149

- Miyazaki, Hayao (November 9, 2006). Nausicaä de la vallée du vent: Recueil d'aquarelles par Hayao Miyazaki [Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Watercolor Collection by Hayao Miyazaki] (Softcover A4) (in French). Glénat. pp. 26, 68, 80, 147–153, 178–179, 188, 192–193. ISBN 2-7234-5180-1. Archived from the original on 2016-04-24. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- Miyazaki, Hayao (September 25, 1982). Ogata, Hideo (ed.). アニメージュ増刊 風の谷のナウシカ [Animage Special Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind'] (Softcover B5) (in Japanese). 1. Michihiro Koganei (first ed.). Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten.

- "Nausicaä Notes, episode 1". Animage (in Japanese). Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten (61): 164–165. June 10, 1983. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- Kanō, Seiji (January 1, 2007) [first published March 31, 2006]. 宮崎駿全書 [Miyazaki Hayao complete book] (in Japanese) (2nd ed.). Tokyo: Film Art Inc. pp. 34–73. ISBN 978-4-8459-0687-1. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- Cavallaro, Dani (2006) "Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind" in The Animé Art of Hayao Miyazaki McFarland & Company p. 48 ISBN 978-0-7864-2369-9

- "Webcat Plus Database entry for Minoru Kobayashi (Japanese)".

- Miyazaki, Hayao (September 5, 1996). 風の谷のナウシカ 宮崎駿水彩画集 [Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind Watercolor collection] (Softcover A4) (in Japanese). ISBN 4-19-810001-2. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- Miyazaki, Hayao (November 6, 2007). The Art of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind: Watercolor Impressions by Hayao Miyazaki (Softcover A4). Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- Miyazaki, Hayao (1995). Viz Graphic Novel, Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind, Perfect Collection volume 1.

- McCarthy, Helen (1999). Hayao Miyazaki Master of Japanese Animation (2002 ed.). Berkeley, Ca: Stone Bridge Press. pp. 30, 39, 41–42, 72–92. ISBN 1880656418. Archived from the original on December 25, 2010.

- Evslin, Bernard (September 1979). Gods, Demigods and Demons [ギリシア神話小事典] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shakai shisō-sha. ISBN 4390110004.

- Backus, Robert L. (1985). The Riverside Counselor's Stories: Vernacular Fiction of Late Heian Japan. Stanford University Press. pp. 41–69, esp. p.63. ISBN 0-8047-1260-3.

- Mayumi, Kozo; Solomon, Barry D.; Chang, Jason (2005). "The ecological and consumption themes of the films of Hayao Miyazaki". Ecological Economics. 54: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.03.012.

- Roberson, James E.; Suzuki, Nobue (2003). Men and Masculinities in Contemporary Japan: Dislocating the Salaryman Doxa. Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 0415244463.

- Saitani, Ryo (January 1995). "I Understand NAUSICAA a Bit More than I Did a Little While Ago". Comic Box. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- McCarthy, Helen (January 1, 2006). 500 Manga Heroes and Villains. Barron's Educational Series. p. 70. ISBN 9780764132018.

- Drazen, Patrick (October 2002). "Flying with Ghibli: The Animation of Hayao Miyazaki and Company". Anime Explosion! The What, Why & Wow of Japanese Animation. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. pp. 253–280. ISBN 1880656728.

- Napier, Susan (2001). "Anime and Global/Local Identity". Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave. p. 20. ISBN 0312238630.

- Miyazaki, Hayao (w, a). Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Tokyo, Japan: Tokuma Shoten

- Hayao Miyazaki (trans. Yann Leguin), Nausicaä de la vallée du Vent. 2 , vol. 2, Glénat , coll. « Ghibli / NAUSICAÄ », November 15, 2000, 180x256mm, p.54 (ISBN 2-7234-3390-0 et ISBN 978-2-7234-3390-7) (in French)

- Hayao Miyazaki (trans. Olivier Huet), Nausicaä de la vallée du Vent. 6, vol. 6, Glénat, coll. « Ghibli / NAUSICAÄ », November 14, 2001, 180x256mm, pp. 147-148 (ISBN 2-7234-3394-3 et ISBN 978-2-7234-3394-5) (in French)

- Yoshida, Kaori (2002). "Evolution of Female Heroes: Carnival Mode of Gender Representation in Anime". Western Washington University. Archived from the original on February 28, 2005. Retrieved November 25, 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Napier, Susan J. (1998). "Vampires, Psychic Girls, Flying Women and Sailor Scouts". In Martinez, Dolores P. (ed.). The Worlds of Japanese Popular Culture: Gender, Shifting Boundaries and Global Culture. Cambridge University Press. p. 106. ISBN 0521631289.

- Høgset, Stig. "Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind". T.H.E.M. Anime Reviews 4.0. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- Napier, Susan J. (2001). "The Enchantment of Estrangement: The shōjo in the world of Miyazaki Hayao". Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave. pp. 135–138. ISBN 0312238630.

- Osmond, Andrew. "Nausicaa and the fantasy of Hayao Miyazaki". nausica.net. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- Zoth, Thomas. "10 Iconic Anime Heroines". Mania Entertainment. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- http://shinku.nichibun.ac.jp/jpub/pdf/jr/IJ1106.pdf

- Toyama, Ryoko. "Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind FAQ". Nausicaa.net. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- Napier, Susan J. (1998). "Vampires, Psychic Girls, Flying Women and Sailor Scouts". In Martinez, Dolores P. (ed.). The Worlds of Japanese Popular Culture: Gender, Shifting Boundaries and Global Culture. Cambridge University Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 0-521-63128-9.

- Wright, Lucy. "Forest Spirits, Giant Insects and World Trees: The Nature Vision of Hayao Miyazaki". Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. University of Toronto Press. 10 (1): 3. doi:10.3138/jrpc.10.1.003. Archived from the original on November 7, 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- Hayao Miyazaki ( trans. Olivier Huet), Nausicaä de la vallée du Vent , vol. 4, Glénat , coll. « Ghibli / NAUSICAÄ », June 13, 2001, page 85 ( ISBN 2-7234-3392-7 and 978-2-7234-3392-1 )

- Hayao Miyazaki ( trans. Olivier Huet), Nausicaä de la vallée du Vent , vol. 7, Glénat , coll. « Ghibli / NAUSICAÄ », March 20, 2002, page 208 ( ISBN 2-7234-3395-1 et 978-2-7234-3395-2 )

- Raphaël Colson and Gaël Régner, (November 1, 2010) Hayao Miyazaki : Cartographie d'un univers, Les Moutons électriques, p.297 ISBN 978-2-915793-84-0 (in French)

- Hiranuma, G.B. "Anime and Academia: Interview with Marc Hairston on pedagogy and Nausicaä". AnimeCraze. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- "Gundam Tops Anime Poll". Anime News Network. September 12, 2000. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- Bordenave, Julie. "Miyazaki Moebius : coup d'envoi" (in French). AnimeLand.com. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- Tiu, Diane. "Xam'd: Lost Memories". T.H.E.M. Anime Reviews 4.0. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- Schodt, Frederik L. (2007). "Beyond Manga". Dreamland Japan : writings on modern manga (5 ed.). Berkeley, Calif: Stone Bridge Press. pp. 279–280. ISBN 9781880656235.

- "Coda: On Your Mark and Nausicaa". Utd500.utdallas.edu. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- Raphaël Colson and Gaël Régner, (November 1, 2010) Hayao Miyazaki : Cartographie d'un univers, Les Moutons électriques, p.226 ISBN 978-2-915793-84-0 (in French)

- Peters, Megan (December 18, 2017). "Did You Notice This Hayao Miyazaki 'Star Wars' Connection?". ComicBook.com.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cosplay of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind |

- Dufayet, Nathalie (2006) "Nausicaä de la Vallée du Vent : la grande saga mythopoétique de Hayao Miyazaki" in Montandon, Alain (e.d.) Mythe et bande dessinée Clermont-Ferrand, France: Presses de Université Blaise-Pascal pp. 39–53 ISBN 2-84516-332-0 (in French)

- Hairston, Marc (2010) "Miyazaki's Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind: Manga into Anime and Its Reception" in Johnson-Woods, Toni (e.d.) Manga: An Anthology of Global and Cultural Perspectives Continuum International Publishing Group ISBN 978-0-8264-2938-4

- Miyazaki, Hayao [1996] (2007) The Art of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind: Watercolor Impressions Viz Media ISBN 1-4215-1499-0

- Napier, Susan J. (2005) Anime: From Akira to Howl's Moving Castle Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 1-4039-7052-1

- Vincent, Marie; Lucas Nicole (2009) "Nausicaa de la vallée du vent, une écologie du monstrueux" in Travelling sur le cinéma d'animation à l'école Editions Le Manuscrit pp. 208–213 ISBN 2-304-03046-7 (in French)