Municipal Asphalt Plant

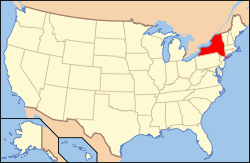

The Municipal Asphalt Plant is located in Manhattan's Upper East Side in New York City. The building was built in 1941.[1]

It currently serves as home to Asphalt Green, a pool and fitness center that opened in 1984.[2]

It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.[3]

Architecture

Built for the Office of the Borough President of Manhattan by architects Ely Jacques Kahn and Robert Allen Jacobs, the Municipal Asphalt Plant was built from 1941 - 1944.

Although an asphalt plant had stood there previously, that asphalt plant had become outdated, as the surrounding neighborhoods transformed from semi-commercial to residential. However, Borough President Stanley Isaacs felt that the neighborhood remained the ideal location for an asphalt plant because the location of the neighborhood minimized the need for the trucking of raw materials through the streets. Therefore, he called for the new asphalt plant to be made in a style that would be an industrial structure, but also be more suited towards the residential character of the neighborhood. The interior of the plant was designed first, and the exterior of the building was designed based on the internal structure. The exterior was designed with four arched ribs, constructed with reinforced concrete. They are spaced twenty two feet apart, eighty four feet and six inches high, and ninety feet wide. The sides of the ribs have windows a third of the way up the walls.

The arch was an efficient design because a more conventional form, such as a rectangle, would have resulted in unused space at the top of the building. The arch further reduced stresses and the need for extraneous reinforced steel. Meeting this need was important because the United States was entering World War II, which made reinforced steel very expensive. One of the most significant aspects of this building is its use of reinforced concrete, a cheaper alternative that had been experimented with in Europe, but not used to any great effect.[4]

The asphalt plant also had two supporting structures: a rectangular storage facility for the raw materials that trucks had brought in and a conveyor belt that brought the raw materials to the mixing plant.[5]

Significant alterations

The surrounding structures, such as the storage facility and the conveyor, were torn down in 1968 because the mixing plant was no longer functioning as a mixing plant. Designated a New York City landmark in 1972, the city added a one hundred yard long recreation field. The City contributed $1.6 million in Federal Community Development Funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. There were plans to remake the Municipal Asphalt Plant into three high rise buildings and a new school. However, George and Annette Murphy challenged these plans and argued for the remaking of the Municipal Asphalt Plant into a recreational center because the area was already twice as dense as the rest of Manhattan, the area had two underutilized schools, and this was the last remaining land that could be used for the recreational center that this area lacked. The architects for this project were Pasanella + Klein. This meant massive changes to the structure of the interior of the building. For instance, the main entrance is now where trucks would have been received and the main gymnasium is now on the top floor where the cement used to be mixed. They also infilled the entrance with glass blocks and used new materials. In 1993, a new building was added to Asphalt Green because the original remaining building had reached maximum capacity. This building was designed by Richard Dattner.[5]

Reception

The Municipal Asphalt Plant has been described as post-modernist. Robert Moses, the Parks Commissioner, called it the "Cathedral of Asphalt" and "the most hideous waterfront structure ever inflicted on a city by a combination of architectural conceit and official bad taste."[6] Walter D. Binger, Commissioner of Borough Works, defended it in a New York Times article and the Museum of Modern Art defended it in an exhibit called "Art in Progress" and a book called "Built in U.S.A, 1932 - 1944."[4] The Museum of Modern Art makes specific reference to the words of Robert Moses, "The New Municipal Asphalt Plant...which Park Commissioner Robert Moses has recently damned with the designation 'Cathedral of Asphalt'...has just been selected by the Museum of Modern Art as '...one of the buildings in the entire country which best represent progress in design and construction during the past twelve years.'"[7] It continues:

"Sharply diversified industrial operations invite sharply differentiated architectural forms. Here there are three distinct and well related elements: conveyor belt, storage building and mixing plant. The main conveyor belt starts at the East River barge moorings, runs under the Drive, then above ground through a diagonal tube (later to be cased in chromium) to the rectangular concrete storage building, where the sand and stone is dropped into a network of bins. From there, underground conveyors run to the third and most prominent unit, the mixing plant. "The bold semi-ellipse of the mixing plant is no affectation. These clean curves represent the most efficient structural form which could house the machinery. The building is of reinforced concrete, its thin vault strengthened by four 90-foothigh ribs. Since the ribs are reinforced with light, selfsupporting steel trusses rather than with the usual rods, no elaborate scaffolding was required while the concrete was poured and dried. Here is industrial architecture which is a distinct asset to its residential neighborhood and an exciting experience for motorists on the adjacent super-highway."

The March 1944 issue of Architectural Forum also described it as functionalistic.[4]

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan above 59th to 110th Streets

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 59th to 110th Streets

References

- Marjorie Pearson and Elizabeth Spencer-Ralph (October 1978). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Municipal Asphalt Plant". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2011-03-25. See also: "Accompanying two photos". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

- Asphalt Green Gym Is Nearly All Roof, and It's Leaky

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "Municipal Asphalt Plant" (PDF). Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 27, 1976.

- "George and Annette Murphy Center at Asphalt Green Sports and Arts Center | docomomo united states". www.docomomo-us.org. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- "Asphalt Green Highlights : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- "Controversial Municipal Asphalt Plant Chosen by Museum of Modern Art as Outstanding Example of Recent American Architecture" (PDF). Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2016-05-01.