Seal of Muhammad

Seal of Muhammad (Arabic ختم الرسول[lower-alpha 1]) is one of the relics of Muhammad kept in the Topkapı Palace by the Ottoman Sultans as part of the Sacred Relics collection. It is allegedly the replica of a seal used by Muhammad on several letters sent to foreign dignitaries.

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier in 1675 reported that the seal was kept in a small ebony box in a niche cut in the wall by the foot of a divan in the relic room at Topkapı. The seal itself is encased in crystal, approximately 3" × 4", with a border of ivory. It has been used as recently as the 17th century to stamp documents.[1]

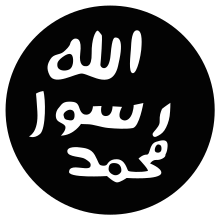

The seal is a rectangular piece of red agate, about 1 cm in length, inscribed with الله / محمد رسول (i.e., Allah "God" in the first line, and Muḥammad rasūl "Muhammad, messenger" in the second). According to Muslim historiographical tradition, Muhammad's original seal was inherited by Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman, but lost by Uthman in a well in Medina. Uthman is said to have made a replica of the seal, and this seal was supposedly found in the capture of Baghdad (1534) and brought to Istanbul.[2]

According to George Frederick Kunz, when Mohammed was about to send a letter to the Emperor Heraclius, he was told he needed a seal to be recognized as coming from him. Mohammed had a seal made of silver, with the words "Mohammed Rasūl Allah" or "Mohammed the Apostle of God." The three words, on three lines, were on the ring, and Mohammed ordered that no duplicate was to be made. After his death, the ring came down to Uthman, who accidentally dropped the ring into the well of Aris. The well was so deep the bottom has never been found, and the ring remained lost. At that time a copy was made, but the loss of the original ring was assumed to be an indication of ill-fortune to come.[3][4][5]

Sir Richard Francis Burton writes that it is a "Tradition of the Prophet" that carnelian is the best stone for a signet ring, and that tradition was still in use in 1868. The carnelian stone is also "a guard against poverty".[6]

A different design of the "seal of Muhammad" is circular, based on Ottoman era manuscript copies of the letters of Muhammad. This is the variant that has become familiar as the "seal of Muhammad."

The authenticity of the letters and of the seal is dubious and has been contested almost as soon as their discovery, although there is little research on the subject. Some scholars such as Nöldeke (1909) consider the currently preserved copy to be a forgery, and Öhrnberg (2007) considers the whole narrative concerning the letter to the Muqawqis to be "devoid of any historical value", and the seal to be fake on paleographical grounds, the writing style being anachronical and hinting at an Ottoman Turkish origin.[8]

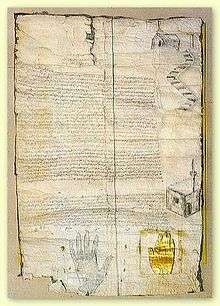

In addition to using a signet ring to seal documents, Mohammed may have also used other techniques to show the provenance of his correspondence. In an alleged letter to the Saint Catherine's Monastery in Egypt, he signed the letter, also called the Ashtiname of Muhammad, by inking his hand and pressing the impression on the paper. The letter granted protection and privileges to the monastery. In part it says: "I shall exempt them from that which may disturb them; of the burdens which are paid by others as an oath of allegiance. They must not give anything of their income but that which pleases them—they must not be offended, or disturbed, or coerced or compelled. Their judges should not be changed or prevented from accomplishing their offices, nor the monks disturbed in exercising their religious order, or the people of seclusion be stopped from dwelling in their cells. No one is allowed to plunder these Christians, or destroy or spoil any of their churches, or houses of worship, or take any of the things contained within these houses and bring it to the houses of Islam. And he who takes away anything therefrom, will be one who has corrupted the oath of God, and, in truth, disobeyed His Messenger." It is sealed with an imprint representing Muhammad's hand.[9]

Notes

- to be distinguished:

- ختم الرسول or خاتم الرسول: "seal of the messenger", the term for Muhammad's signet ring (also خاتم محمد "seal of Muhammad");

- خاتم النبيين: "seal of the prophets", the title given to Muhammad;

- خاتم النبوة: "seal of prophethood", the name of the egg-shaped protrusion on Muhammad's shoulder-blade;

- also, محمد خاتمی by coincidential near-homography, the name of Mohammad Amir Khatam.

References

- Tavernier, Jean-Baptiste. "Nouvelle Relation de l'Intérieur du Sérail du Grand Seigneur", 1675.

- Rachel Milstein, "Futuh-i Haramayn: sixteenth-century illustrations of the Hajj route" in: David J Wasserstein and Ami Ayalon (eds.), Mamluks and Ottomans: Studies in Honour of Michael Winter , Routledge, 2013, p. 191 (on the point of the tradition being controversial referencing 15th-century scholar al-Samhudi). William Muir in The Caliphate: Its Rise, Decline and Fall (1892) gives an account of the legend on Uthman's loss of the seal, the fruitless search for it, the calamity of the omen, and Uthman's eventual consent "to supply the lost signet by another of like fashion".

- Ibn Khaldun. 1865. "Prolégomènes Historiques." Prolégomènes d'Ebn-Khaldoun, texte arabe, publié, d'après les manuscrits de la Bibliothèque impériale.. Volume XX, pt i, pp 61–62. Paris.

- Kunz, George F. Rings for the Finger, from the Earliest Known Times to the Present. Philadelphia and London, 1917. Page 141. See: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b361035;view=1up;seq=213

- Ibn Khaldūn, Etienne Quatremère, and William MacGuckin Slane. Prolégomènes d'Ebn-Khaldoun, texte arabe, publié, d'après les manuscrits de la Bibliothèque impériale. Paris: F. Didot frères, fils et cie, imprimeurs de l'Institut impériale de France, 1858.

- Burton, Richard Francis. Supplementary Nights, in Seven Volumes. [Place of publication not identified]: Private, n.d. Volume V, page 52.

- "the original of the letter was discovered in 1858 by Monsieur Etienne Barthelemy, member of a French expedition, in a monastery in Egypt and is now carefully preserved in Constantinople. Several photographs of the letter have since been published. The first one was published in the well-known Egyptian newspaper Al-Hilal in November 1904" Muhammad Zafrulla Khan, Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1980 (chapter 12). The drawing of the document published in Al-Hilal was reproduced in David Samuel Margoliouth, Mohammed and the Rise of Islam, London (1905), p. 365, which is the source of this image.

- "The story of this particular embassy to al-Mukawkis must be considered as legendary and devoid of any historical value. The parchment which was thought to be the original of Muhammad's letter to al-Mukawkis—it was found in a monastery at Akhmim in 1850 (cf. the publication by Belin, in JA [1854], 482-518)—has been recognized almost from the beginning as a fake, on both historical as well as paleographical grounds (J. Karabacek, Beiträge zur Geschichte der Mazjaditen, Leipzig 1874, 35 n. 47; Nöldeke-Schwally, Geschichte des Qorans, i, Leipzig 1909, 190)." K. Öhrnberg, Encyclopedia of Islam Second Edition s.v. "Muḳawḳis", (2007).

- Ratliff, "The monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai and the Christian communities of the Caliphate."