Parietal cell

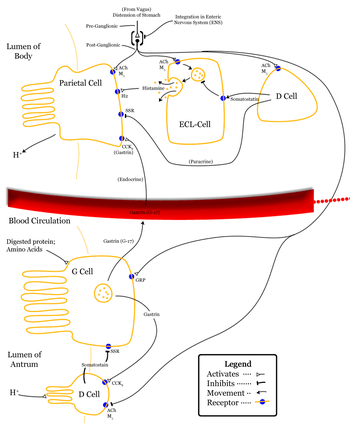

Parietal cells (also known as oxyntic or delomorphous cells) are the epithelial cells that secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl) and intrinsic factor. These cells are located in the gastric glands found in the lining of the fundus and in the cardia of the stomach.[1] They contain an extensive secretory network (called canaliculi) from which the HCl is secreted by active transport into the stomach. The enzyme hydrogen potassium ATPase (H+/K+ ATPase) is unique to the parietal cells and transports the H+ against a concentration gradient of about 3 million to 1, which is the steepest ion gradient formed in the human body. Parietal cells are primarily regulated via histamine, acetylcholine and gastrin signaling from both central and local modulators (see 'Regulation')..

| Parietal cell | |

|---|---|

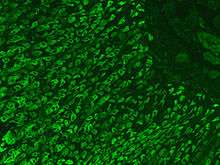

Human parietal cells (pink staining) – stomach | |

Control of stomach acid | |

| Details | |

| Location | Stomach |

| Function | Gastric acid, intrinsic factor secretion |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | exocrinocytus parietalis |

| MeSH | D010295 |

| TH | H3.04.02.1.00033 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Structure

Canaliculus

A canaliculus is an adaptation found on gastric parietal cells. It is a deep infolding, or little channel, which serves to increase the surface area, e.g. for secretion. The parietal cell membrane is dynamic; the numbers of canaliculi rise and fall according to secretory need. This is accomplished by the fusion of canalicular precursors, or "tubulovesicles", with the membrane to increase surface area, and the reciprocal endocytosis of the canaliculi (reforming the tubulovesicles) to decrease it. 00

Function

Hydrochloric acid secretion

Hydrochloric acid is formed in the following manner:

- Hydrogen ions are formed from the dissociation of carbonic acid. Water is a very minor source of hydrogen ions in comparison to carbonic acid. Carbonic acid is formed from carbon dioxide and water by carbonic anhydrase.

- The bicarbonate ion (HCO3−) is exchanged for a chloride ion (Cl−) on the basal side of the cell and the bicarbonate diffuses into the venous blood, leading to an alkaline tide phenomenon.

- Potassium (K+) and chloride (Cl−) ions diffuse into the canaliculi.

- Hydrogen ions are pumped out of the cell into the canaliculi in exchange for potassium ions, via the H+/K+ ATPase. These receptors are increased in number on lumenal side by fusion of tubulovesicles during activation of parietal cells and removed during deactivation. This receptor maintains a million-fold difference in proton concentration. ATP is provided by the numerous mitochondria.

As a result of the cellular export of hydrogen ions, the gastric lumen is maintained as a highly-acidic environment. The acidity aids in digestion of food by promoting the unfolding (or denaturing) of ingested proteins. As proteins unfold, the peptide bonds linking component amino acids are exposed. Gastric HCl simultaneously cleaves pepsinogen, a zymogen, into active pepsin, an endopeptidase that advances the digestive process by breaking the now-exposed peptide bonds, a process known as proteolysis.

Regulation

Parietal cells secrete acid in response to three types of stimuli:[2]

- Histamine, stimulates H2 histamine receptors (most significant contribution).

- Acetylcholine, from parasympathetic activity via the vagus nerve and enteric nervous system, stimulating M3 receptors.[3]

- Gastrin, stimulating CCK2 receptors (least significant contribution, but also causes histamine secretion by local ECL cells)

Activation of histamine through H2 receptor causes increases intracellular cAMP level while Ach through M3 receptor and gastrin through CCK2 receptor increases intracellular calcium level. These receptors are present on basolateral side of membrane.

Increased cAMP level results in increased protein kinase A. Protein kinase A phosphorylates proteins involved in the transport of H+/K+ ATPase from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane. This causes resorption of K+ ions and secretion of H+ ions. The pH of the secreted fluid can fall by 0.8.

Gastrin primarily induces acid-secretion indirectly, increasing histamine synthesis in ECL cells,which in turn signal parietal cells via histamine release/H2 stimulation.[4] Gastrin itself has no effect on the maximum histamine-stimulated gastric acid secretion.[5]

The effect of histamine, acetylcholine and gastrin is synergistic, that is, effect of two simultaneously is more than additive of effect of the two individually. It helps in non-linear increase of secretion with stimuli physiologically.[6]

Intrinsic factor secretion

Parietal cells also produce intrinsic factor. Intrinsic factor is required for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the diet. A long-term deficiency in vitamin B12 can lead to megaloblastic anemia, characterized by large fragile erythrocytes. Pernicious anaemia results from autoimmune destruction of gastric parietal cells, precluding the synthesis of intrinsic factor and, by extension, absorption of Vitamin B12. Pernicious anemia also leads to megaloblastic anemia. Atrophic gastritis, particularly in the elderly, will cause an inability to absorb B12 and can lead to deficiencies such as decreased DNA synthesis and nucleotide metabolism in the bone marrow.

Clinical significance

- Peptic ulcers can result from over-acidity in the stomach. Antacids can be used to enhance the natural tolerance of the gastric lining. Antimuscarinic drugs such as pirenzepine or H2 antihistamines can reduce acid secretion. Proton pump inhibitors are more potent at reducing gastric acid production since that is the final common pathway of all stimulation of acid production.

- In pernicious anemia, autoantibodies directed against parietal cells or intrinsic factor cause a reduction in vitamin B12 absorption. It can be treated with injections of replacement vitamin B12 (methylcobalamin, hydroxocobalamin or cyanocobalamin).

- Achlorhydria is another autoimmune disease of the parietal cells. The damaged parietal cells are unable to produce the required amount of gastric acid. This leads to an increase in gastric pH, impaired digestion of food and increased risk of gastroenteritis.

See also

- Gastric chief cell

- Digestion

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Discovery and Development of Proton Pump Inhibitors

- List of human cell types derived from the germ layers

References

- Hunt, A; Harrington, D; Robinson, S (4 June 2014). "Vitamin B12 deficiency" (PDF). BMJ. 349: g5226. doi:10.1136/bmj.g5226. PMID 25189324. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- Boulpaep, Walter (2009). Medical Physiology. Philadelphia: Saunders. pp. 898–899. ISBN 978-1-4160-3115-4.

- "Gastric acid secretion - Homo sapiens". KEGG. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- Waldum, Helge L., Kleveland, Per M., et al. (2009)'Interactions between gastric acid secretagogues and the localization of the gastrin receptor', Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology,44:4,390 — 393

- Kleveland PM, Waldum HL, Larsson M. Gastric acid secretion in the totally isolated, vascularly perfused rat stomach. A selective muscarinic-1 agent does, whereas gastrin does not, augment maximal histamine-stimulated acid secretion. Scand J Gastroenterol 1987;/22:/705�13.

- Ganong's Review of Medical Physiology 24th edition. LANGE.

External links

- Illustration of Chief cells and Parietal cells at anatomyatlases.org

- The Parietal Cell: Mechanism of Acid Secretion at vivo.colostate.edu

- Histology image: 11303loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - Digestive System: Alimentary Canal: fundic stomach, gastric glands, lumen"

- Nosek, Thomas M. "Section 6/6ch4/s6ch4_8". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24.

- Nosek, Thomas M. "Section 6/6ch4/s6ch4_14". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24.

- Parietal cell antibody

- Antibody to GPC