Renal medulla

The renal medulla is the innermost part of the kidney. The renal medulla is split up into a number of sections, known as the renal pyramids. Blood enters into the kidney via the renal artery, which then splits up to form the interlobar arteries. The interlobar arteries each in turn branch into arcuate arteries, which in turn branch to form interlobular arteries, and these finally reach the glomeruli. At the glomerulus the blood reaches a highly disfavourable pressure gradient and a large exchange surface area, which forces the serum portion of the blood out of the vessel and into the renal tubules. Flow continues through the renal tubules, including the proximal tubule, the Loop of Henle, through the distal tubule and finally leaves the kidney by means of the collecting duct, leading to the renal pelvis, the dilated portion of the ureter.

| Renal medulla | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| System | Urinary system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Medulla renalis |

| MeSH | D007679 |

| TA | A08.1.01.020 |

| FMA | 74268 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The renal medulla (Latin renes medulla = kidney middle) contains the structures of the nephrons responsible for maintaining the salt and water balance of the blood. These structures include the vasa rectae (both spuria and vera), the venulae rectae, the medullary capillary plexus, the loop of Henle, and the collecting tubule.[1] The renal medulla is hypertonic to the filtrate in the nephron and aids in the reabsorption of water.

Blood is filtered in the glomerulus by solute size. Ions such as sodium, chloride, potassium, and calcium are easily filtered, as is glucose. Proteins are not passed through the glomerular filter because of their large size, and do not appear in the filtrate or urine unless a disease process has affected the glomerular capsule or the proximal and distal convoluted tubules of the nephron.

Though the renal medulla only receives a small percentage of the renal blood flow, the oxygen extraction is very high, causing a low oxygen tension and more importantly, a critical sensitivity to hypotension, hypoxia, and blood flow.[2] The renal medulla extracts oxygen at a ratio of ~80% making it exquisitely sensitive to small changes in renal blood flow. The mechanisms of many perioperative renal insults are based on the disruption of adequate blood flow (and therefore oxygen delivery) to the renal medulla.[2]

Interstitium

The medullary interstitium is the tissue surrounding the loop of Henle in the medulla. It functions in renal water reabsorption by building up a high hypertonicity, which draws water out of the thin descending limb of the loop of Henle and the collecting duct system.hypertonicity, in turn, is created by an efflux of urea from the inner medullary collecting duct.[3]

Pyramids

| Renal pyramids | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| System | Urinary system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Pyramides renales |

| MeSH | D007679 |

| TA | A08.1.01.020 |

| FMA | 74268 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Renal pyramids (or malpighian pyramids or Malpighi's pyramids named after Marcello Malpighi, a seventeenth-century anatomist) are cone-shaped tissues of the kidney. In humans, the renal medulla is made up of 10 to 18 of these conical subdivisions.[4][5] The broad base of each pyramid faces the renal cortex, and its apex, or papilla, points internally towards the pelvis. The pyramids appear striped because they are formed by straight parallel segments of nephrons' Loops of Henle and collecting ducts. The base of each pyramid originates at the corticomedullary border and the apex terminates in a papilla, which lies within a minor calyx, made of parallel bundles of urine collecting tubules.

Papilla

The renal papilla is the location where the renal pyramids in the medulla empty urine into the minor calyx in the kidney. Histologically it is marked by medullary collecting ducts converging to form a papillary duct to channel the fluid. Transitional epithelium begins to be seen.

Clinical significance

Some chemicals toxic to the kidney, called nephrotoxins, damage the renal papillae. Damage to the renal papillae may result in death to cells in this region of the kidney, called renal papillary necrosis. The most common toxic causes of renal papillary necrosis are NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, acetylsalicylic acid, and phenylbutazone, in combination with dehydration. Perturbed renal papillary development has also been shown to be associated with onset of functional obstruction and renal fibrosis.[6][7][8]

Renal papillary damage has also been associated with nephrolithiasis and can be quantified according to the papillary grading score, which accounts for contour, pitting, plugging and randall plaque.[9]

Additional Images

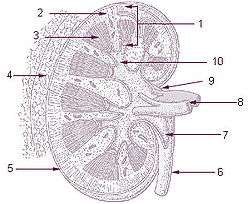

- Renal medulla

- Renal medulla

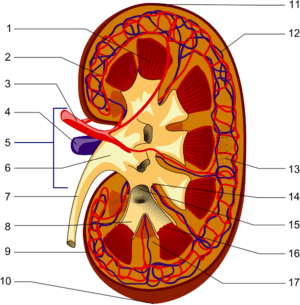

- Renal papilla

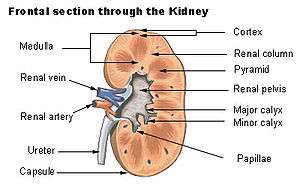

Frontal section through the kidney

Frontal section through the kidney Vertical section of kidney. (Label "medullary sub." visible near top.)

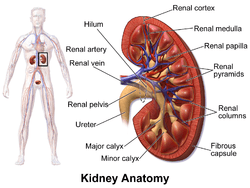

Vertical section of kidney. (Label "medullary sub." visible near top.) Kidney anatomy, with pyramids labeled at right

Kidney anatomy, with pyramids labeled at right

See also

- Medullipin

- Kokko and Rector Model, a theory to explain how a gradient is generated in the inner medulla

- Renal sinus

- Medullary interstitium

- Renal capsule

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1221 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Netter's, plate 337

- Miller's Anesthesia, 8th edition. 553-554.

- Walter F., PhD. Boron (2003). Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approaoch. Elsevier/Saunders. p. 1300. ISBN 1-4160-2328-3. Page 837

- Young, Barbara; O'Dowd, Geraldine; Woodford, Phillip (2014). Wheater's Functional Histology (6 ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-7020-4747-3.

- "Renal Pyramids Function, Anatomy & Diagram | Body Maps". Healthline.

- Wilkinson, L; Kurniawan, ND; Phua, YL; Nguyen, MJ; Li, J; Galloway, GJ; Hashitani, H; Lang, RJ; Little, MH (August 2012). "Association between congenital defects in papillary outgrowth and functional obstruction in Crim1 mutant mice" (PDF). The Journal of Pathology. 227 (4): 499–510. doi:10.1002/path.4036. PMID 22488641.

- Phua, YL; Gilbert, T; Combes, A; Wilkinson, L; Little, MH (April 2016). "Neonatal vascularization and oxygen tension regulate appropriate perinatal renal medulla/papilla maturation". The Journal of Pathology. 238 (5): 665–76. doi:10.1002/path.4690. PMID 26800422.

- Phua, YL; Martel, N; Pennisi, DJ; Little, MH; Wilkinson, L (April 2013). "Distinct sites of renal fibrosis in Crim1 mutant mice arise from multiple cellular origins". The Journal of Pathology. 229 (5): 685–96. doi:10.1002/path.4155. PMID 23224993.

- Cohen, Andrew J.; Borofsky, Michael S.; Anderson, Blake B.; Dauw, Casey A.; Gillen, Daniel L.; Gerber, Glenn S.; Worcester, Elaine M.; Coe, Fredric L.; Lingeman, James E. (2017). "Endoscopic Evidence That Randall's Plaque is Associated with Surface Erosion of the Renal Papilla". Journal of Endourology. 31 (1): 85–90. doi:10.1089/end.2016.0537. ISSN 0892-7790. PMC 5220550. PMID 27824271.

External links

- Anatomy figure: 40:03-02 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Anatomy photo:40:06-0107 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Posterior Abdominal Wall: Internal Structure of a Kidney"

- Histology image: 15901loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Urinary System: neonatal kidney"

- posteriorabdomen at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (renalpelvis)