Moschorhinus

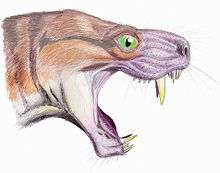

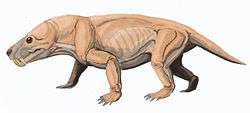

Moschorhinus is an extinct genus of therocephalian in the family Akidnognathidae, with only one species: M. kitchingi. It was a carnivorous, lion-sized synapsid which has been found in the Late Permian to Early Triassic of the South African Karoo Supergroup. It had a broad, blunt snout which bore long, straight canines. It appears to have replaced the gorgonopsids ecologically, and hunted much like a big cat. While most abundant in the Late Permian, it survived a little after the Permian Extinction, though these Triassic individuals had stunted growth.

| Moschorhinus | |

|---|---|

_(18228737998).jpg) | |

| Illustration of the skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Therocephalia |

| Family: | †Akidnognathidae |

| Genus: | †Moschorhinus Broom, 1920 |

| Type species | |

| Moschorhinus kitchingi Broom, 1920 | |

Taxonomy

The genus name Moschorhinus is derived from the Ancient Greek words μόσχος (mos'-khos) moschos for calf or young animal, and rhin/rhino- for nose or snout, in reference to its short, broad snout. The species name, kitchingi, refers to Mr. James Kitching, who originally found (but did not describe) the specimen.[1]

Kitching discovered the holotype specimen, a skull (best preserved, the palate), in the Karoo Supergroup in South Africa, near the village of Nieu-Bethesda. It was first described by paleontologist Robert Broom in 1920.[1] It is now one of the best known and most recognizable therapsids of the supergroup.[2]

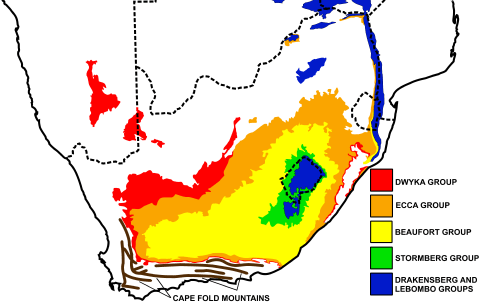

Moschorhinus remains have been found most prominently in the Upper Permian to Lower Triassic Beaufort Group.[2][3][4]

Classification

Moschorhinus is a therocephalian, a member of the clade Eutheriodontia and the sister taxon to cynodonts and modern mammals. Moschorhinus is classified into the family Akidnognathidae, along with other large, carnivorous theraspids with strong skulls and large upper canines.[5]

Moschorhinus took over the niche once controlled by gorgonopsids. Both groups were built much like big cats. Following the extinction of Moschorhinus by the Triassic, cynodonts took over a similar niche.[5]

Description

The skull is similar to that of the Gorgonopsids, with large temporal fenestrae (three in total as a synapsid) and a convexly bowed palate. The skull ranged in size to comparable to a monitor lizard, to those of a lion. They possess a characteristically short, broad snout. They possess a pair of prominently long incisors, similar to the canines of saber toothed cats.[5][6]

Lateral view of Moschorhinus jaw, showing range of motion necessary for such large incisors, and upper palatal fenestrae of snout. (From van Valkenburgh and Jenkins, 2002).[5]

Snout

The snout of Moschorhinus is characteristically short and broad. The blunt tip of the snout features a ridge running down the midline to the frontal bone.[5][3] The lower jaw is much broader than that of any other therocephalian.[5][3] The upper snout projects a bit beyond the incisors in juveniles.[3]

The nostrils were large and positioned towards the tip of the snout.[3]

Teeth

_(18228730598).jpg)

_(18418228921).jpg)

Moschorhinus is thought to have had a dental formula of I6.C1.M3, with 6 incisors, 1 canine, and 3 molars in either side of the upper jaw.[1]

The incisors are housed in the premaxillae. They are large, curve slightly, and have a bell-shaped cross-section. They had smooth cutting surfaces, and, unlike those of other therocephalians, lacked facets or striae resulting from abrasion and wear.[3]

The large saber-like canines are held within the maxillae, and are quickly identifiable features of Moschorhinus. They are especially thick and strong, and uniquely circular in cross-section. In length, these sabers are comparable to gorgonopsids. While there is no real modern analogue, the most similar living example would be the clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa).[5]

Like other therocephalians, Moschorhinus had a reduced number of molars which were housed in the maxillae. In most therocephalians, the “teeth,” or rather toothlike projection (denticulations) of the pterygoid bones, are greatly reduced or missing, and in Moschorhinus they are absent.[3][7]

Skull roof

Tracing the roof of the skull, Moschorhinus possesses small prefrontal bones above the eyes, followed by large, widened frontal bones. The parietals form a narrow sagittal crest along the midline of the skull, which houses a very basic pineal foramen.[1][3] Indentations can be seen in the temporal fossae, depressions on either side of the crest, indicating the presence of many blood vessels and nerves supplying the brain.[8]

Eye sockets

The lacrimal bone is larger than the reduced prefrontal, and forms the majority of the eye socket. The lacrimal has a bony boss (a rounded knob) on the orbit, and a large foramen towards its inner side. The lower edge of the eye socket is formed the jugal and maxillary bones.[1] The jugal ends at the eye socket, and is not convex, as in several later thercephalians.[3]

Palate

Overall, the palate is convex, with a broad, triangular vomer, with paired tubercles, rounded projections pointing ventrally,[5][3] similar to other akidnognathids.[1] The palatine bones (forming the back of the roof of the mouth) are enlarged and thick, especially on their outer edges where they are joined to the maxilla. On their inner edges, the palatines are joined to the pterygoid and vomer on the nose, forming part of the circumference of the nasal cavity. Between the palatine and maxilla, just behind the canines, are large foramens, presumably to allow for nerves. A slanting ridge along the middle of the palatine presumably supported a soft palate, which allowed air to travel between the nose and the lungs.[5]

The sabers require the mouth to open widely for use, making feeding difficult. The closely related Promoschorynchus shows stiff folds (choanal crest) on the border of the nasal passage and the throat, used to keep it open and to allow for breathing while eating. The development of a secondary palate in the skull gradually evolved in therocephalians, and the choanal crest is featured in all later therocephalians.[7]

Paleobiology

It is presumed that Moschorhinus was a cat-like predator, being able to pierce skin and hold onto struggling prey with its long canines. This is the first record of this kind of hunting technique. Given its sturdily designed, thick snout, enormous canines, and powerful jaw muscles, Moschorhinus appears to have been a daunting predator.[5]

Paleoecology

Many vertebrate fossils have been uncovered in the Karoo Basin. Other therocephalians from the same rock level are Tetracynodon and Promoschorhynchus.[2] Moschorhinus specimens were the only large therocephalians.[9][3]

Moschorhinus seems to have gone extinct in the Early Triassic after the Permian Extinction by 252 mya,[10][11] along with 80–95% of animal species, due to a mass hypoxia event. This appears to have led to stunted growth,[2] intense seasons, reduced ecosystem diversity, and a loss of forests.[3] Fossil evidence shows that Triassic Moschorhinus grew faster than Permian ones, resulting in reduced body size in the former, largely believed to be an effect of the harsher environmental variability after the Permian Extinction (Lilliput effect).[2][12][3] Permian skulls average 207 mm (8.1 in) in length, while that of Triassic skull is only 179 mm (7.0 in).[2] Nonetheless, Triassic Moschorhinus were the largest therocephalians of their time.[2][9]

References

- Broom R (1920). "On Some New Therocephalian Reptiles from the Karroo Beds of South Africa". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 351–354.

- Huttenlocker AK, Botha-Brink J (2013). "Body size and growth patterns in the therocephalian Moschorhinus kitchingi (Eutheriodontia) before and after the end-Permian extinction in South Africa". Paleobiology. 39 (2): 253–77. doi:10.1666/12020.

- Huttenlocker, Adam (2013). The Paleobiology of South African Therocephalian Therapsids (Amniota, Synapsida) and the Effects of the End-Permian Extinction on Size, Growth, and Bone Microstructure (Ph.D). University of Washington.

- Rubidge, B. S.; Sidor, C. A. (2001). "Evolutionary Patterns Among Permo-Triassic Therapsids". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 32: 449–480. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114113.

- van Valkenburgh B, Jenkins I (2002). "EVOLUTIONARY PATTERNS IN THE HISTORY OF PERMO-TRIASSIC AND CENOZOIC SYNAPSID PREDATORS" (PDF). Paleontological Society Papers. 8: 267–88. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-17.

- Huttenlocker Adam (2009). "An Investigation into the Cladistic Relationships and Monophyly of Therocephalian Theraspids". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 157 (4): 865–891. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00538.x.

- Maier W, van den Heever J, Durand F (1996). "New therapsid specimens and the origin of the secondary hard and soft palate of mammals". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 34: 9–19. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.1996.tb00805.x.

- Durand J F (1991). "A revised descripction of the skull of moschorhinus (therapsida, therocephalia)". Annals of the South African Museum. 99: 381–413.

- Christian A. Sidor; Roger M. H. Smith; Adam K. Huttenlocker; Brandon R. Peecook (2014). "New Middle Triassic Tetrapods from the Upper Fremouw Formation of Antarctica and Their Depositional Setting". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (4): 793–801. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.837472.

- Peter D Ward; Jennifer Botha; Roger Buik; Michiel O. De Kock; Douglas H. Erwin; Geoffrey H Garrison; Joseph L Kirschvink; Roger Smith (2005). "Abrupt and Gradual Extinction Among Late Permian Land Vertebrates in the Karoo Basin, South Africa". Science. 307 (5710): 709–714. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.503.2065. doi:10.1126/science.1107068. PMID 15661973.

- Botha J, Smith RM (2006). "Rapid vertebrate recuperation in the Karoo Basin of South Africa following the End-Permian extinction" (PDF). Journal of African Earth Sciences. 45 (4–5): 502–14. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2006.04.006.

- Richard J Twitchett (2007). "The Lilliput effect in the aftermath of the end-Permian extinction event" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 252 (1–2): 132–144. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.11.038.