Lilliput effect

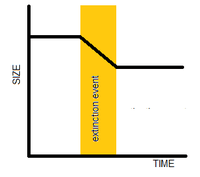

The Lilliput effect is a decrease in body size in animal species which have survived a major extinction.[1] There are several hypotheses as to why these patterns appear in the fossil record, some of which are: the survival of small taxa, dwarfing of larger lineages, and the evolutionary miniaturization from larger ancestral stocks.[2] The term was coined in 1993 by Adam Urbanek in his paper concerning the extinction of graptoloids[3] and is derived from the island of Lilliput inhabited by a miniature race of people in Gulliver’s Travels. This size decrease may just be a temporary phenomenon restricted to the survival period of the extinction event. In 2019 Atkinson et coined the term the Brobdingnag effect[4] to describe a related phenomenon operating in the opposite direction, whereby new species evolving after the Triassic-Jurassic mass extinction originated at small body sizes before undergoing a size increase[4]. The term is also from Gulliver’s Travels where Brobnignag is a land inhabited by a race of giants.

Significance

Trends in body size changes are seen throughout the fossil record in many organisms, and major changes (shrinking and dwarfing) in body size can significantly affect the morphology of the animal itself as well as how it interacts with the environment.[2] Since Urbanek's publication several researchers have described a decrease in body size in fauna post-extinction event, although not all use the term "Lilliput effect" when discussing this trend in body size decrease.[5][6][7]

The Lilliput effect has been noted by several authors to have occurred after the Permian-Triassic mass extinction event. Early Triassic fauna, both marine and terrestrial, is notably smaller than those preceding and following in the geologic record.[1]

Potential Causes of Smaller Body Sizes

Extinction of Larger Taxa

The extinction event may affect the larger-bodied organisms more severely, leaving smaller bodies taxa behind.[1] As such, the smaller organisms which now make up the population will take time to grow into larger body sizes.[1] These larger animals may be evolutionarily selected against for several reasons, including high energy requirements for which the resources may not longer be available, increased generation times compared to smaller bodied organisms, and smaller population sizes which would be more severely affected by environmental changes.[1]

Development of New Organisms

New animal taxa tend to originally develop at a small size, as hypothesized by S.M. Stanley.[8]

Shrinking of Surviving Taxa

It is possible that organisms within a lineage reduced in body size during the extinction event, so that the organisms surviving the event were smaller than their ancestors living before the extinction event occurred.[1]

References

- Twitchett, R.J. (2007). "The Lilliput effect in the aftermath of the end-Permian extinction event". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 252 (1–2): 132–144. Bibcode:2007PPP...252..132T. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.11.038.

- Harries, P.J.; Knorr, P.O. (2009). "What does the 'Lilliput Effect' mean?". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 284 (1–2): 4–10. Bibcode:2009PPP...284....4H. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.08.021.

- Urbanek, Adam (1993). "Biotic Crises in the History of Upper Silurian Graptoloids: A Palaeobiological Model". Historical Biology. 7: 29–50. doi:10.1080/10292389309380442.

- Atkinson, Jed W.; Wignall, Paul B.; Morton, Jacob D.; Aze, Tracy (2019). "Body size changes in bivalves of the family Limidae in the aftermath of the end-Triassic mass extinction: the Brobdingnag effect". Palaeontology. 62 (4): 561–582. doi:10.1111/pala.12415. ISSN 1475-4983. Archived from the original on 14 Jan 2019.

- Kaljo, D (1996). "Diachronous recovery patterns in Early Silurian corals, graptolites and acritarchs". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 102 (1): 127–134. Bibcode:1996GSLSP.102..127K. doi:10.1144/gsl.sp.1996.001.01.10.

- Girard, C; Renaud, S (1996). "Size variations in conodonts in response to the upper Kellwasser crisis (upper Devonian of the Montagne Noire, France)". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série IIA. 323: 435–442.

- Jeffery, C.H. (2001). "Heart urchins at the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary: a tale of two clades". Paleobiology. 27: 140–158. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2001)027<0140:huatct>2.0.co;2.

- Stanley, S.M. (1973). "An explanation for Cope's Rule". Evolution. 27 (1): 1–26. doi:10.2307/2407115. JSTOR 2407115.