Montgomery Ward

Montgomery Ward Inc. is the name of two successive brand-related American retail enterprises. It can refer either to the original Montgomery Ward, a pioneering mail order and department store retailer which operated between 1872 and 2001, and to the current catalog and online retailer also known as Wards.

Montgomery Ward retailer logo, also the store's 1982–1995 and 2004–present logo | |

| Private – Original incarnation, mail order and department store Current incarnation, online retailer and catalog merchant | |

| Industry | Retail |

| Fate | Bankruptcy in 2000; Full liquidation in 2001 namesake retailer launched in 2004 after purchase of trademarks |

| Founded | 1872 (as mail order company and later department store, defunct 2001) 2004 (as current online retailer) |

| Defunct | June 2001 (original company) |

| Headquarters | Original company in Chicago, Illinois, United States 2004 to 2008: namesake company Monroe, Wisconsin, United States |

Key people | Original company: 1872 founder, Aaron Montgomery Ward namesake company: John Baumann, president of parent company Swiss Colony |

| Products | Clothing, footwear, bedding, furniture, jewelry, beauty products, appliances, housewares, tools, and electronics. |

| Brands | Riverside Airline Powr-Kraft |

| Divisions | Electric Avenue Wards Kids Montgomery Ward Catalog Montgomery Wards Auto Express |

| Website | wards |

History

Original Montgomery Ward (1872–2001)

Company origins

Montgomery Ward was founded by Aaron Montgomery Ward in 1872. Aaron had conceived of the idea of a dry goods mail-order business in Chicago, Illinois, after several years of working as a traveling salesman among rural customers. He observed that rural customers often wanted "city" goods, but their only access to them was through rural retailers who had little competition and did not offer any guarantee of quality. Ward also believed that by eliminating intermediaries, he could cut costs and make a wide variety of goods available to rural customers, who could purchase goods by mail and pick them up at the nearest train station.

Ward started his business at his first office, either in a single room at 825 North Clark Street[1] or in a loft above a livery stable on Kinzie Street, between Rush and State Streets.[2] He and two partners raised $1,600 and issued their first catalog in August 1872. It consisted of an 8 in × 12 in (20 cm × 30 cm) single-sheet price list, listing 163 items for sale with ordering instructions for which Ward had written the copy. His two partners left the following year, but he continued the struggling business and was joined by his future brother-in-law, George Robinson Thorne.

In the first few years, the business was poorly received by rural retailers. Considering Ward a threat, they sometimes publicly burned his catalog. Despite the opposition, however, the business grew at a fast pace over the next several decades, fueled by demand primarily from rural customers who were inspired by the wide selection of items that were unavailable to them locally. Customers were also inspired by the innovative company policy of "satisfaction guaranteed or your money back", which Ward began in 1875. Ward turned the copywriting over to department heads but continued poring over every detail in the catalog for accuracy.

In 1883, the company's catalog, which became popularly known as the "Wish Book", had grown to 240 pages and 10,000 items. In 1896, Wards encountered its first serious competition in the mail order business, when Richard Warren Sears introduced his first general catalog. In 1900, Wards had total sales of $8.7 million, compared to $10 million for Sears, and both companies struggled for dominance during much of the 20th century. By 1904, Wards had expanded such that it mailed three million catalogs, weighing 4 lb (1.8 kg) each, to customers.[3]

In 1908, the company opened a 1.25-million-square-foot (116,000 m2) building stretching along nearly one-quarter mile of the Chicago River, north of downtown Chicago. The building, known as the Montgomery Ward & Co. Catalog House, served as the company headquarters until 1974, when the offices moved across the street to a new tower designed by Minoru Yamasaki. The catalog house was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1978 and a Chicago historic landmark in May 2000.[4] In the decades before 1930, Montgomery Ward built a network of large distribution centers across the country in Baltimore, Fort Worth, Kansas City, Oakland, Portland, and St. Paul. In most cases, these reinforced concrete structures were the largest industrial structures in their respective locations. The Baltimore Montgomery Ward Warehouse and Retail Store was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2000.[5][6]

.jpg)

Expansion into retail outlets

Aaron Montgomery Ward died in 1913, after 41 years of running the catalog business. The company president, William C. Thorne (the co-founder's eldest son) died in 1917 and was succeeded by Robert J. Thorne, who retired in 1920 due to ill health.

In 1926, the company broke with its mail-order-only tradition when it opened its first retail outlet store in Plymouth, Indiana. It continued to operate its catalog business while pursuing an aggressive campaign to build retail outlets in the late 1920s. In 1928, two years after opening its first outlet, it had opened 244 stores. By 1929, it had more than doubled its number of outlets to 531. Its flagship retail store in Chicago was located on Michigan Avenue between Madison and Washington streets.[7]

In 1930, the company declined a merger offer from its rival chain Sears. Losing money during the Great Depression, Wards alarmed its major investors, including J. P. Morgan. In 1931, Morgan hired a new president, Sewell Avery, who cut staff levels and stores, changed lines, hired store rather than catalog managers, and refurbished stores. These actions caused the company to become profitable before the end of the 1930s.[8]

Wards was very successful in its retail business. "Green awning" stores dotted hundreds of small towns across the country. Larger stores were built in the major cities. By the end of the 1930s, Montgomery Ward had become the country's largest retailer, and Sewell Avery became the company's chief executive officer.[9]

In 1939, as part of a Christmas promotional campaign, staff copywriter Robert L. May created the character Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer and an eponymous illustrated poem. In 1946, the store distributed six million copies of the poem as a storybook, and Gene Autry popularized the song nationally.

In 1946, the Grolier Club, a society of bibliophiles in New York City, exhibited the Wards catalog alongside Webster's Dictionary as one of 100 American books chosen for their influence on life and culture of the people.

Government seizure

In April 1944, four months into a nationwide strike by the company's 12,000 workers, U.S. Army troops seized the company's Chicago offices. The action was ordered due to Avery's refusal to settle the strike as requested by the Roosevelt administration, concerned about the adverse effect on the delivery of goods in wartime.[10] Avery had refused to comply with a War Labor Board order to recognize the unions and institute the terms of a collective bargaining agreement. Eight months later, with Montgomery Ward continuing to refuse to recognize the unions, President Roosevelt issued an executive order seizing all of Montgomery Ward's property nationwide, citing the War Labor Disputes Act as well as his power under the Constitution as commander-in-chief. In 1945, Truman ended the seizure and the Supreme Court ended the pending appeal as moot.[11]

Decline

After World War II, Sewell Avery believed the country would fall back into a recession or even a depression. He decided to not open any new stores, and did not even permit expenditure for paint to freshen the existing stores. His plan was to bank profits to preserve liquidity when the recession or depression hit, and then buy up his retail competition. However, without new stores or any investment back into the business, Montgomery Ward declined in sales volume compared to Sears; many have blamed the conservative decisions of Avery, who seemed to not understand the changing economy of the postwar years. As new shopping centers were built after the war, Sears was perceived to have gotten better locations than Wards. Nonetheless, for many years Wards was still the nation's third-largest department store chain.

In 1955, investor Louis Wolfson waged a high-profile proxy fight to obtain control of the board of Montgomery Ward. The new board forced the resignation of Avery. This fight led to a state court decision that Illinois corporations were not entitled to stagger elections of board members."[12]

Meanwhile, throughout the 1950s, the company was slow to respond to the general movement of the American middle class to suburbia. While its competitors Sears, JCPenney, Macy's, Gimbels, and Dillard's established new anchor outlets in the growing number of suburban shopping malls, Avery and succeeding top executives had been reluctant to pursue such expansion. They stuck to their downtown and main street stores until the company had lost too much market share to compete with its rivals. After Avery's departure in 1955, it was two years before the first new store since the 1930s was opened. Wards tried to become more aggressive with store opening, but it was too late. As the existing stores looked worn and disheveled, malls would often not allow Wards to build there. Its catalog business had also begun to slip by the 1960s.

In 1961, company president John Barr hired Robert Elton Brooker to lead Montgomery Ward as president in its turnaround. Brooker brought with him a number of key new management people, including Edward Donnell, former manager of Sears' Los Angeles stores. The new management team achieved the turnaround reducing the number of suppliers from 15,000 to 7,000 and the number of brands being carried dropped from 168 to 16. Ward's private brands were given 95 percent of the volume compared with 40 percent in 1960. The results of these changes were lower handling costs and higher quality standards. Buying was centralized but store operations were decentralized, under a new territory system modeled after Sears.[13] In 1966, Ed Donnell was named company president. Brooker continued as chairman and chief executive officer until the mid 1970s. In 1968, Brooker helped engineer a friendly merger with Container Corporation of America; the new company was named MARCOR. In 1974, Mobil oil company bought MARCOR.[14]

During the 1970s, the company continued to struggle. In 1973, its 102nd year in business, it purchased a small discount store chain, the Miami-based Jefferson Stores, renaming these locations Jefferson Ward.[15] Mobil, flush with cash from the recent rise in oil prices, acquired Montgomery Ward in 1976. By 1980, Mobil realized that the Montgomery Ward stores were doing poorly in comparison to the Jefferson stores, and decided that high quality discount units, along the lines of Dayton Hudson Company's Target stores, would be the retailer's future. Within 18 months, management quintupled the size of the operation, now called Jefferson Ward, to more than 40 units and planned to convert one-third of Montgomery Ward's existing stores to the Jefferson Ward model. The burden of servicing the new stores fell to the tiny Jefferson staff, who were overwhelmed by the increased store count, had no experience in dealing with some of the product lines they now carried, and were unfamiliar with buying for northern markets. Almost immediately, Jefferson had turned from a small moneymaker into a large drain on profits.[16] The company sold the chain's 18-store northern division to Bradlees, a division of Stop & Shop, in 1985. The remaining stores closed.[17]

In 1985, the company closed its catalog business after 113 years and began an aggressive policy of renovating its remaining stores. It restructured many of the store layouts in the downtown areas of larger cities and affluent neighborhoods into boutique-like specialty stores, as these were drawing business from traditional department stores. In 1988, the company management undertook a successful $3.8 billion leveraged buyout, making Montgomery Ward a privately held company.[18]

In 1987, the company began a push into consumer electronics, opening stand alone "Electric Avenue" stores. Montgomery Ward greatly expanded its electronics presence by shifting from a predominantly private label mix to an assortment dominated by major brands such as Sony, Toshiba, Hitachi, Panasonic, JVC, and others. They advertised using the Eddy Grant song Electric Avenue. Vice President Vic Sholis, later president of the Tandy Retail Group (McDuff, VideoConcepts, and Incredible Universe), led this strategy. In 1994, revenues increased 94% largely due to Montgomery Ward's tremendously successful direct-marketing arms. For a short period, the company reentered the mail-order business via a licensing agreement with Fingerhut. However, by the mid-1990s, sales margins eroded in the competitive electronics and appliance hardlines, which traditionally were Montgomery Ward's strongest lines.

In 1989, the company's small electronics leader, Jim Hamilton (later known as the father of computer retailing), offered a deeply discounted PC for $1499. The promotion was a huge success and led to the development of the nation's first branded computer store department. Space was allocated in three Sacramento stores to create SOHO (small office/home office) departments. Since many of the brands like Hewlett Packard and Panasonic would not disrupt their dealer channel and sell direct to Montgomery Ward, Hamilton had to create relationships with distributors. When the Sacramento stores opened, their shelves included products from Hewlett Packard and OkiData, companies which had never been in a national retailer. The test was a major success and the SOHO department was rolled out to all Montgomery Ward locations. Montgomery Ward was one of the first retailers to carry consumer products from IBM, Apple, Compaq, Hewlett Packard, Western Digital and many others. The SOHO Department was carved into a separate division of the company and quickly became Montgomery Ward's largest revenue producing division, with over $4 billion in revenues.

In 1994, Wards acquired the now-defunct New England retail chain Lechmere.

Bankruptcy, restructuring, and liquidation

By the 1990s even its rivals began to lose ground to low-price competition from Kmart, Wal-Mart, and especially Target, which eroded even more of Montgomery Ward's traditional customer base. In 1997, it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, emerging from protection by the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of Illinois in August 1999 as a wholly owned subsidiary of GE Capital, which was by then its largest shareholder. As part of a last-ditch effort to remain competitive, the company closed over 100 retail locations[19] in 30 U.S. states (including all the Lechmere and Electric Avenue stores),[20] abandoned the specialty store strategy, renamed and rebranded the chain as simply Wards (although unrelated, Wards was the original name for the now-defunct Circuit City), and spent millions of dollars to renovate its remaining outlets to be flashier and more consumer-friendly. GE Capital reneged on promises of further financial support of Montgomery Ward's restructuring plans.[21]

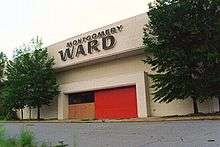

On December 28, 2000, after lower-than-expected sales during the Christmas season, the company announced it would cease operating, close its remaining 250 retail outlets, and lay off its 37,000 employees. All stores closed within weeks of the announcement. The subsequent liquidation was at the time the largest retail Chapter 7 bankruptcy liquidation in American history (this would be later surpassed by the 2009 and 2018 store closures of Circuit City and Toys 'R' Us). Roger Goddu, Montgomery Ward's CEO, received an offer from JCPenney to become CEO, but he declined under pressure from GE Capital. One of the last closing stores was Salem, Oregon, the location of its human resources division. Montgomery Ward was liquidated by the end of May 2001, ending a 129-year enterprise.

Termination of pension plan

In 1999, Montgomery Ward completed a standard termination of its $1.1 billion employee pension plan (Wards Retirement Plan WRP and Retired/Terminated Associate Plan RTAP), which at that time had an alleged estimated surplus of $270 million.[22] The termination of the pension plan included 30,000 Wards retirees and 22,000 active employees who were employed by Wards in 1999. According to tax rules at that time (to avoid paying a 50% federal excise tax on the plan's termination), Wards then placed 25% of the plan's surplus into a replacement pension plan, and paid federal tax of just 20% on the balance of the surplus. The final result: the estimated remaining $25 to $50 million of the employee pension plan surplus went to Wards free of income taxes, because the company, which was in Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings, had huge operating losses.[23] In reality, Wards received an alleged estimated $25 to $50 million for ending the employee pension plan and avoided paying hundreds of thousands in yearly pension premiums to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation. Employees and retirees vested in the pension plan were given a choice of receiving an annuity from an insurance company or a lump sum payment.

Distribution centers

Five of the seven massive catalog distribution centers Montgomery Ward built between 1921 and 1929 remain. Four have been renovated for adaptive reuse. The buildings are perhaps the most tangible legacy of Montgomery Ward. Two others have been demolished for various types of redevelopment.

- In Baltimore, the 1925 warehouse, an eight-story, 1.3-million-square-foot (120,000 m2) building at 1800 Washington Blvd.[24] southwest of downtown Baltimore, now known as Montgomery Park, has been restored for office use. It has a green building with a green roof, storm water reutilization systems, and extensive use of recycled building materials.[25] It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2000 as the Montgomery Ward Warehouse and Retail Store.[26]

- The eight-story Fort Worth facility at West 7th St and Carroll[27] was built in 1928 to replace the previous operation in a former Chevrolet assembly plant across the street. In its history, the warehouse survived a flood in 1949 that reached the second floor[28] and a direct hit from a tornado in 2000.[29] After the demise of the company, developers renovated the structure as a mixed-use condominium project and retail center known as Montgomery Plaza.[30]

- The Portland, Oregon, center at NW 27th and Vaughn,[31] ceased operation as a warehouse in 1976. A developer purchased the property in 1984 and renamed it Montgomery Park, converting it for offices making it the second-largest office building in Portland.[32][33]

- The Kansas City distribution center at St. John Street and North Belmont Boulevard houses the Super Flea flea market.[34]

- The Menands (just outside Albany) catalog distribution center on Route 32 was also built in 1929. It did later house a store as well, and was renovated after some time vacant into office space, now known as the Riverview Center.

- The St. Paul, Minnesota, center at 1450 University Ave West was the fourth of the distribution centers to be built and employed up to 2,500 employees in the 1920s. It had nearly 1.2 million square feet (110,000 m2) or approximately 27 acres under roof, making it the largest building in St. Paul at the time. The last remaining section of the original building was demolished in 1996. The site was redeveloped as a shopping center called Midway Marketplace.[35]

- The Oakland, California, facility, constructed in 1923, was an eight-story 950,000-square-foot (88,000 m2) structure of reinforced concrete frame that was the largest industrial building in Oakland.[36] After years of community organizing that urged city leaders to either demolish or re-purpose the site, despite opposition by preservation groups,[37] the building at 2875 International Boulevard was demolished in 2003. It has been replaced by the Cesar Chavez Education Center, an elementary school.[38]

As online retailer

At its height, the original Montgomery Ward was one of the largest retailers in the US. After its demise, the familiarity of its brand meant its name, corporate logo, and advertising were considered valuable intangible assets. In 2004, catalog marketer Direct Marketing Services Inc. (DMSI), an Iowa-based direct marketing company, purchased much of the intellectual property assets of the former Wards, including the "Montgomery Ward" and "Wards" trademarks, for an undisclosed amount.[39]

DMSI applied the brand to a new online and catalog-based retailing operation, with no physical stores, headquartered in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. DMSI then began operating under the Montgomery Ward branding, and managed to get it up and running in three months. The new firm began operations in June 2004, selling essentially the same categories of products as the former brand, but as a new, smaller catalog.[39]

DMSI's version of Montgomery Ward was not the same company as the original. The new company did not honor its predecessors' obligations, such as gift cards and items sold with a lifetime guarantee. David Milgrom, then president of the DMSI-owned firm, said in an interview with David Carpenter of Associated Press: "We're rebuilding the brand, and we want to do it right."[39]

In July 2008, DMSI announced it was on the auction block, with sale scheduled for the following month. On August 5, 2008, the catalog retailer Swiss Colony purchased DMSI. Swiss Colony—which changed its name to Colony Brands Inc. on June 1, 2010—announced it would keep the Montgomery Ward catalog division open. The website launched September 10, 2008, with new catalogs mailing in February 2009.[40] A month before the catalog's launch, Swiss Colony president John Baumann told United Press International the retailer might also resurrect Montgomery Ward's Signature and Powr-Kraft store brands.[41]

See also

- Montgomery Ward Building (disambiguation) (numerous buildings)

- Montgomery Ward Company Complex

References

Notes

- Robertson, Patrick (November 8, 2011). Robertson's Book of Firsts: Who Did What For the First Time. New York City: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1596915794.

- "A. Montgomery Ward Park". Chicago Park District. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "About Us". Montgomery Ward. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "Landmarks: Montgomery Ward & Co. Catalog House". City of Chicago. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- "Montgomery Ward Warehouse and Retail Store". Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "Montgomery Ward's History". December 9, 2006. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Ingham, John (1983). Biographical Dictionary of American Business Leaders, Volume 1. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 30–31. ISBN 9780313239076.

- Ingham, John (1983). Biographical Dictionary of American Business Leaders, Volume 1 Biographical Dictionary of American Business Leaders. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 30–31. ISBN 9780313239076.

- Horne, Louther (April 30, 1944). "Montgomery Ward Seizure Stirs Wide Criticism". The New York Times. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

The seizure by troops on Wednesday of the Chicago units of Montgomery Ward Co., second largest of the country's merchandising corporations, has raised a Central West storm of criticism of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's action among business and industrial leaders and the usual Republican denouncers of the national Administration.

- "This Day in History – December 27, 1944: FDR seizes control of Montgomery Ward". History Channel. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- Emerson, Frank D. (January 1, 1956). "Congressional Investigation of Proxy Regulation: A Case Study of Committee Exploratory Methods and Techniques". Villanova Law Review. Villanova University. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "GENERAL MERCHANDISE RETAILING IN AMERICA:", American National Business Hall of Fame, 25 October 2014. Retrieved on 8 December 2017.

- "Mobil Corporation", Encyclopedia Britannica, Retrieved on 8 December 2017.

- Talley, Jim; Herzog, Carl (July 12, 1985). "Jefferson Ward Store Closed". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- Aldrich, Dave. "It's the Montgomery, Not the Ward". Pleasant Family Shopping. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- Talley, Jim (November 1, 1985). "Jefferson Closes Stores". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- Rosenberg, Joyce M. "Mobil Selling Montgomery Ward in $3.8 billion LBO CX Filed mfstfpasn". AP NEWS. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- "Company News; Montgomery Ward Emerges From Bankruptcy". The New York Times. August 3, 1999. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- TELEVISIONARCHIVES (October 28, 2009). "Montgomery Ward going out of business commercial". Retrieved March 14, 2018 – via YouTube.

- "Montgomery Ward to close doors". The Cincinnati Enquirer. December 29, 2000. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "Montgomery Ward Holding Corp., Chicago, might terminate its $1 billion..." Pensions&Investments. July 18, 1997. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Chandler, Susan (March 18, 1999). "WARDS TERMINATING PENSION PLAN IN MOVE TO END BANKRUPTCY". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "1800 Washington Blvd, Baltimore, MD-street view". Google maps. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "Montgomery Park ushers in a new era of entrepreneurial spirit". Montgomery Park. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "W 7th & Carroll Street, Ft. Worth, TX- Street view". Google maps. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "Trinity River flood of May 17, 1949 covered most of near west side". Fort Worth Architecture. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "Montgomery Ward Retail Store & Warehouse". Fort Worth Architecture. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "About Montgomery Plaza: Now". Montgomery Plaza. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "NW Vaughn St & NW 27th Ave, Portland, OR-street view". Google Maps. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- Oregon Historical Quarterly Archived December 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Projects: Montgomery Park". Naito Development. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- "Our Location". Super Flea. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- Millett, Larry (September 15, 1996). Twin Cities Then and Now. Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0873513272.

- "Montgomery Ward Company". Oakland Public Library. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- League for Protection of Oakland's Architectural and Historic Resources v. Oakland, 52 Cal.App.4th 896 A074348 (February 10, 1997).

- "Cesar Chavez Education Center". Collaborative for High Performance Schools. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- Carpenter, David (December 9, 2006). "Montgomery Ward brand name is back, as an Internet and catalog retailer". Lincoln Journal Star. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Tierney, Jim (August 8, 2008). "Swiss Colony Acquires DMSI". Multichannel Merchant. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- Harrington, Gerry (January 14, 2009). "Montgomery Ward catalog to return". United Press International. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

Further reading

- Boorstin, Daniel J. (1973). "A. Montgomery Ward's Mail-Order Business". Chicago History. 2 (3). pp. 142–152.

- Latham, Frank B. (1972). 1872–1972: A Century of Serving Consumers. The Story of Montgomery Ward.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Montgomery Ward. |

- Official website

- Christmas Catalogs and Holiday Wishbooks (Website) – Dozens of Montgomery Ward Christmas Catalogs.