Mishpatim

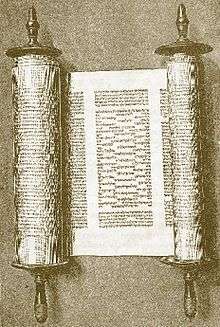

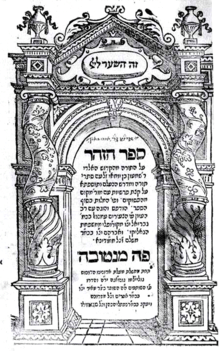

Mishpatim (Hebrew: מִּשְׁפָּטִים — Hebrew for "laws," the second word of the parashah) is the eighteenth weekly Torah portion (Hebrew: פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the sixth in the Book of Exodus. The parashah sets out a series of laws, which some scholars call the Covenant Code. It reports the people's acceptance of the covenant with God. The parashah constitutes Exodus 21:1–24:18. The parashah is made up of 5,313 Hebrew letters, 1,462 Hebrew words, 118 verses, and 185 lines in a Torah scroll (Hebrew: סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1]

Jews read it the eighteenth Sabbath after Simchat Torah, generally in February or, rarely, in late January.[2] As the parashah sets out some of the laws of Passover, Jews also read part of the parashah, Exodus 22:24–23:19, as the initial Torah reading for the second intermediate day (Hebrew: חוֹל הַמּוֹעֵד, Chol HaMoed) of Passover. Jews also read the first part of parashah Ki Tisa, Exodus 30:11–16, regarding the half-shekel head tax, as the maftir Torah reading on the special Sabbath Shabbat Shekalim, which often falls on the same Sabbath as Parashat Mishpatim (as it does in 2023, 2026, 2028, and 2029).

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or Hebrew: עליות, aliyot.[3]

First reading — Exodus 21:1–19

In the first reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), God told Moses to give the people laws concerning Hebrew slaves,[4] homicide,[5] striking a parent,[6] kidnapping,[7] insulting a parent,[8] and assault.[9]

Second reading — Exodus 21:20–22:3

The second reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah) addresses laws of assault,[10] a homicidal animal,[11] damage to livestock,[12] and theft.[13]

Third reading — Exodus 22:4–26

The third reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah) addresses laws of damage to crops,[14] bailment,[15] seduction,[16] sorcery,[17] bestiality,[18] apostasy,[19] wronging the disadvantaged,[20] and lending.[21]

Fourth reading — Exodus 22:27–23:5

The fourth reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah) addresses laws of duties to God,[22] judicial integrity,[23] and humane treatment of an enemy.[24]

Fifth reading — Exodus 23:6–19

The fifth reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah) addresses laws concerning the disadvantaged,[25] false charges,[26] bribery,[27] oppressing the stranger,[28] the sabbatical year for crops (Hebrew: שמיטה, Shmita),[29] the Sabbath,[30] the mention of other gods,[31] the Three Pilgrimage Festivals (Hebrew: שָׁלוֹשׁ רְגָלִים, Shalosh Regalim),[32] sacrifice (Hebrew: קָרְבָּן, korban),[33] and First Fruits (Hebrew: ביכורים, Bikkurim).[34]

Sixth reading — Exodus 23:20–25

In the short sixth reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), God promised to send an angel with the Israelites to bring them to the place God had prepared.[35] God directed the Israelites to obey the angel, for if they did, then God would be an enemy to their enemies.[36] The Israelites were not to serve other gods, but to serve only God.[37]

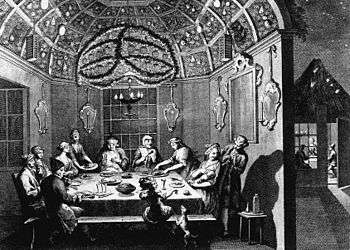

Seventh reading — Exodus 23:26–24:18

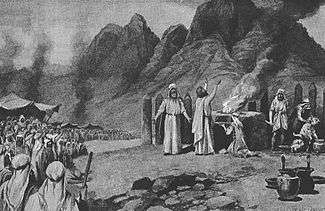

In the seventh reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), God promised reward for obedience to God.[38] God invited Moses, Aaron, Nadab, Abihu, and 70 elders to bow to God from afar.[39] Moses repeated the commandments to the people, who answered: "All the things that the Lord has commanded we will do!"[40] Moses then wrote the commandments down.[41] He set up an altar and some young Israelite men offered sacrifices.[42] Moses took a book referred to as the Book of the Covenant and read the covenant aloud to the people, who once again affirmed that they would follow it.[43] Moses took blood from the sacrifices and dashed it on the people.[44] Moses, Aaron, Nadab, Abihu, and the 70 elders of Israel then ascended, saw God, ate, and drank.[45] Moses and Joshua arose, and Moses ascended Mount Sinai, leaving Aaron and Hur in charge of legal matters.[46] A cloud covered the mountain, hiding the Presence of the Lord for six days, appearing to the Israelites as a fire on the top of the mountain.[47] Moses went inside the cloud and remained on the mountain for 40 days and nights.[48]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[49]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020, 2023, 2026 . . . | 2021, 2024, 2027 . . . | 2022, 2025, 2028 . . . | |

| Reading | 21:1–22:3 | 22:4–23:19 | 23:20–24:18 |

| 1 | 21:1–6 | 22:4–8 | 23:20–25 |

| 2 | 21:7–11 | 22:9–12 | 23:26–30 |

| 3 | 21:12–19 | 22:13–18 | 23:31–33 |

| 4 | 21:20–27 | 22:19–26 | 24:1–6 |

| 5 | 21:28–32 | 22:27–23:5 | 24:7–11 |

| 6 | 21:33–36 | 23:6–13 | 24:12–14 |

| 7 | 21:37–22:3 | 23:14–19 | 24:15–18 |

| Maftir | 21:37–22:3 | 23:14–19 | 24:15–18 |

In ancient parallels

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Exodus chapters 21–22

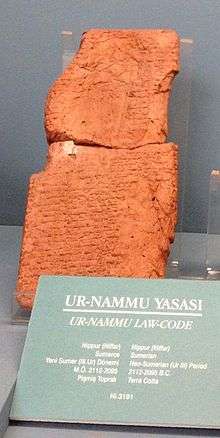

The laws in the parashah find parallels in several ancient law codes.[50]

| Topic of Law | In Exodus 21–23 | In Ancient Parallels |

|---|---|---|

| Debt Slavery | Exodus 21:2: If you buy a Hebrew servant, six years he shall serve; and in the seventh he shall go out free for nothing. |  Hammurabi's Code Code of Hammurabi 117 (1750 BCE): If anyone fails to meet a claim for debt, and sells himself, his wife, his son, and daughter for money or gives them away to forced labor: They shall work for three years in the house of the man who bought them, or the proprietor, and in the fourth year they shall be set free.[51] |

| The Maid-Servant-Wife | Exodus 21:7–11: 7And if a man sells his daughter to be a maid-servant, she shall not go out as the men-servants do. 8If she does not please her master, who has espoused her to himself, then he shall let her be redeemed; he shall have no power to sell her to a foreign people, seeing he has dealt deceitfully with her. 9And if he espouses her to his son, he shall deal with her after the manner of daughters. 10If he takes another wife, he shall not diminish her food, her clothing, and her conjugal rights. 11And if he does not give her these three, then she shall go out for nothing, without money. | Code of Hammurabi 146–47 (1750 BCE):

146If a man takes a wife and she gives this man a maid-servant as wife and she bears him children, and then this maid assumes equality with the wife: because she has borne him children, her master shall not sell her for money, but he may keep her as a slave, reckoning her among the maid-servants. 147If she has not borne him children, then her mistress may sell her for money.[52] |

| Homicide | Exodus 21:12–14: 12He who strikes a man, so that he dies, shall surely be put to death. 13And if a man does not lie in wait, but God causes it to come to hand; then I will appoint you a place to which he may flee. 14And if a man comes presumptuously upon his neighbor, to slay him with guile; you shall take him from My altar, that he may die. |  Code of Ur-Nammu Code of Hammurabi 206–208 (1750 BCE): 206If during a quarrel one man strikes another and wounds him, then he shall swear, "I did not injure him wittingly," and pay the physicians. 207If the man dies of his wound, he shall swear similarly, and if he (the deceased) was a free-born man, he shall pay half a mina in money. 208If he was a freed man, he shall pay one-third of a mina.[54] |

| A Fight | Exodus 21:18–19: 18And if men contend, and one strikes the other with a stone, or with his fist, and he does not die, but keeps his bed; 19if he rises again, and walks abroad on his staff, then he who struck him shall go free; only he shall pay for the loss of his time, and shall cause him to be thoroughly healed. | Code of Hammurabi 206 (1750 BCE): If during a quarrel one man strikes another and wounds him, then he shall swear, "I did not injure him wittingly," and pay the physicians.[55]

Hittite Laws 10 (1500 BCE): If anyone injures a man so that he causes him suffering, he shall take care of him. Yet he shall give him a man in his place, who shall look after his house until he recovers. But if he recovers, he shall give him six shekels of silver. And to the physician this one shall also give the fee.[56] |

| Assault on a Debt Slave | Exodus 21:20–21: 20And if a man strikes his bondman, or his bondwoman, with a rod, and he dies under his hand, he shall surely be punished. 21Notwithstanding if he continue a day or two, he shall not be punished; for he is his property. | Code of Hammurabi 115–116 (1750 BCE): 115If anyone has a claim for grain or money upon another and imprisons him; if the prisoner dies in prison a natural death, the case shall go no further. 116If the prisoner dies in prison from blows or maltreatment, the master of the prisoner shall convict the merchant before the judge. If he was a free-born man, the son of the merchant shall be put to death; if it was a slave, he shall pay one-third of a mina of gold, and all that the master of the prisoner gave he shall forfeit.[57] |

| Harm to a Pregnant Woman | Exodus 21:20–25: 22And if men strive together, and hurt a woman with child, so that her fruit depart, and yet no harm follows, he shall surely be fined, according as the woman's husband shall lay upon him; and he shall pay as the judges determine. 23But if any harm follows, then you shall give life for life, 24eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, 25burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe. | Sumerian Code 1 (1800 BCE): If one father of one household accidentally strikes the daughter of another, other, and she miscarries, then the fine is ten shekels.[58]

Code of Hammurabi 209–214 (1750 BCE): 209If a man strikes a free-born woman so that she loses her unborn child, he shall pay ten shekels for her loss. 210If the woman dies, his daughter shall be put to death. 211If a woman of the free class loses her child by a blow, he shall pay five shekels in money. 212If this woman dies, he shall pay half a mina. 213If he strikes the maid-servant of a man, and she loses her child, he shall pay two shekels in money. 214If this maid-servant dies, he shall pay one-third of a mina.[59] .jpg) Hittite Laws Hittite Laws 17–18 (1500 BCE): 17If anyone causes a free woman to miscarry, [if] it is her tenth month, he shall pay 10 shekels of silver, if it is her fifth month, he shall pay 5 shekels of silver. He shall look to his house for it. 18If anyone causes a female slave to miscarry, if it is her tenth month, he shall pay 5 shekels of silver.[60] Middle Assyrian Laws 50–52 (1200 BCE): 50If a man struck a married woman and caused her to miscarry, the striker's wife will be treated in the same way: He will pay for the unborn child on the principle of a life for a life. But if (the first) woman died, the man is to be executed: he will pay for the unborn child on the principle of a life for a life. If (the first) woman's husband has no son, and she has been struck causing a miscarriage, the striker will be executed, even if the child was a girl: He will still pay for the unborn child on the principle of a life for a life. 51If a man struck a married woman who does not rear her children and caused her to miscarry, he is to pay two talents of lead. 52If a man struck a harlot and caused her to miscarry, he is to be struck with the same number and type of blows: In this way he will pay on the principle of a life for a life.[61] |

| An Eye for an Eye | Exodus 21:23–25: 23But if any harm follows, then you shall give life for life, 24eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, 25burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe. | Laws of Eshnunna 42–43 (1800 BCE): 42If a man bites the nose of another man and thus cuts it off, he shall weigh and deliver 60 shekels of silver; an eye — 60 shekels; a tooth — 30 shekels; an ear — 30 shekels; a slap to the cheek — he shall weigh and deliver 10 shekels of silver. 43If a man should cut off the finger of another man, he shall weigh and deliver 40 shekels of silver.[62]

Code of Hammurabi 196–201 (1750 BCE): 196If a man puts out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out. 197If he breaks another man's bone, his bone shall be broken. 198If he puts out the eye of a freed man, or breaks the bone of a freed man, he shall pay one gold mina. 199If he puts out the eye of a man's slave, or breaks the bone of a man's slave, he shall pay one-half of its value. 200If a man knocks out the teeth of his equal, his teeth shall be knocked out. 201If he knocks out the teeth of a freed man, he shall pay one-third of a gold mina.[63] |

| An Ox that Gores | Exodus 21:28–36: 28And if an ox gores a man or a woman, that they die, the ox shall surely be stoned, and its flesh shall not be eaten; but the owner of the ox shall go free. 29But if the ox was wont to gore in times past, and warning has been given to its owner, and he has not kept it in, but it has killed a man or a woman; the ox shall be stoned, and its owner also shall be put to death. 30If there is laid on him a ransom, then he shall give for the redemption of his life whatever is laid upon him. 31Whether it has gored a son, or has gored a daughter, according to this judgment shall it be done to him. 32If the ox gores a bondman or a bondwoman, he shall give to their master 30 shekels of silver, and the ox shall be stoned. . . . 35And if one man's ox hurts another's, so that it dies; then they shall sell the live ox, and divide the price of it; and the dead also they shall divide. 36Or if it be known that the ox was wont to gore in times past, and its owner has not kept it in; he shall surely pay ox for ox, and the dead beast shall be his own. | Laws of Eshnunna 53–55 (1800 BCE): 53If an ox gores another ox and thus causes its death, the two ox-owners shall divide the value of the living ox and the carcass of the dead ox. 54If an ox is a gorer and the ward authorities so notify the owner, but he fails to keep his ox in check, and it gores a man and thus causes his death, the owner of the ox shall weigh and deliver 40 shekels of silver. 55If it gores a slave and thus causes his death, he shall weigh and deliver 15 shekels of silver.[64]

Code of Hammurabi 251–252 (1750 BCE): 251If an ox is a goring ox, and it is shown that he is a gorer, and he does not bind his horns, or fasten the ox up, and the ox gores a free-born man and kills him, the owner shall pay one-half a mina in money. 252If he kills a man's slave, he shall pay one-third of a mina.[65] |

| Son or Daughter | Exodus 21:31: Whether it has gored a son, or has gored a daughter, according to this judgment shall it be done to him. | Code of Hammurabi 229–231 (1750 BCE): 229If a builder builds a house for someone, and does not construct it properly, and the house that he built falls in and kills its owner, then that builder shall be put to death. 230If it kills the son of the owner, the son of that builder shall be put to death. 231If it kills a slave of the owner, then he shall pay slave for slave to the owner of the house.[66] |

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[67]

Exodus chapters 21–23

Professor Benjamin Sommer of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America argued that Deuteronomy 12–26 borrowed whole sections from the earlier text of Exodus 21–23.[68]

Exodus chapter 21

In three separate places — Exodus 21:22–25; Leviticus 24:19–21; and Deuteronomy 19:16–21 — the Torah sets forth the law of "an eye for an eye."

Exodus chapter 22

Exodus 22:20 admonishes the Israelites not to wrong the stranger, "for you were strangers in the land of Egypt." (See also Exodus 23:9; Leviticus 19:33–34; Deuteronomy 1:16; 10:17–19; 24:14–15 and 17–22; and 27:19.) Similarly, in Amos 3:1, the 8th century BCE prophet Amos anchored his pronouncements in the covenant community's Exodus history, saying, "Hear this word that the Lord has spoken against you, O children of Israel, against the whole family that I brought up out of the land of Egypt."[69]

Exodus 22:25–26 admonishes: "If you take your neighbor's garment in pledge, you must return it to him before the sun sets; it is his only clothing, the sole covering for his skin." Similarly, in Amos 2:8, Amos condemned people of Judah who "recline by every altar on garments taken in pledge."

Exodus chapter 23

Passover

Exodus 23:15 refers to the Festival of Passover. In the Hebrew Bible, Passover is called:

- "Passover" (Hebrew: פֶּסַח, Pesach);[70]

- "The Feast of Unleavened Bread" (Hebrew: חַג הַמַּצּוֹת, Chag haMatzot);Exodus 12:17; 23:15; 34:18; Leviticus 23:6; Deuteronomy 16:16; Ezekiel 45:21; Ezra 6:22; 2 Chronicles 8:13; 30:13,35:17.[71] and

- "A holy convocation" or "a solemn assembly" (Hebrew: מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh).Exodus 12:16; Leviticus 23:7–8; Numbers 28:18,[72]

Some explain the double nomenclature of "Passover" and "Feast of Unleavened Bread" as referring to two separate feasts that the Israelites combined sometime between the Exodus and when the Biblical text became settled.[73] Exodus 34:18–20 and Deuteronomy 15:19–16:8 indicate that the dedication of the firstborn also became associated with the festival.

Some believe that the "Feast of Unleavened Bread" was an agricultural festival at which the Israelites celebrated the beginning of the grain harvest. Moses may have had this festival in mind when in Exodus 5:1 and 10:9 he petitioned Pharaoh to let the Israelites go to celebrate a feast in the wilderness.[74]

"Passover," on the other hand, was associated with a thanksgiving sacrifice of a lamb, also called "the Passover," "the Passover lamb," or "the Passover offering."Exodus 12:11,Deuteronomy 16:2,Ezra 6:20;2 Chronicles 30:15,35:1,[75]

Exodus 12:5–6, Leviticus 23:5, and Numbers 9:3 and 5, and 28:16 direct "Passover" to take place on the evening of the fourteenth of Aviv (Nisan in the Hebrew calendar after the Babylonian captivity). Joshua 5:10, Ezekiel 45:21, Ezra 6:19, and 2 Chronicles 35:1 confirm that practice. Exodus 12:18–19, 23:15, and 34:18, Leviticus 23:6, and Ezekiel 45:21 direct the "Feast of Unleavened Bread" to take place over seven days and Leviticus 23:6 and Ezekiel 45:21 direct that it begin on the fifteenth of the month. Some believe that the propinquity of the dates of the two Festivals led to their confusion and merger.[74]

Exodus 12:23 and 27 link the word "Passover" (Hebrew: פֶּסַח, Pesach) to God's act to "pass over" (Hebrew: פָסַח, pasach) the Israelites' houses in the plague of the firstborn. In the Torah, the consolidated Passover and Feast of Unleavened Bread thus commemorate the Israelites' liberation from Egypt. Exodus 12:42; 23:15; 34:18; Numbers 33:3; Deuteronomy 16:1,[76]

The Hebrew Bible frequently notes the Israelites' observance of Passover at turning points in their history. Numbers 9:1–5 reports God's direction to the Israelites to observe Passover in the wilderness of Sinai on the anniversary of their liberation from Egypt. Joshua 5:10–11 reports that upon entering the Promised Land, the Israelites kept the Passover on the plains of Jericho and ate unleavened cakes and parched grain, produce of the land, the next day. 2 Kings 23:21–23 reports that King Josiah commanded the Israelites to keep the Passover in Jerusalem as part of Josiah's reforms, but also notes that the Israelites had not kept such a Passover from the days of the Biblical judges nor in all the days of the kings of Israel or the kings of Judah, calling into question the observance of even Kings David and Solomon. The more reverent 2 Chronicles 8:12–13, however, reports that Solomon offered sacrifices on the Festivals, including the Feast of Unleavened Bread. And 2 Chronicles 30:1–27 reports King Hezekiah's observance of a second Passover anew, as sufficient numbers of neither the priests nor the people were prepared to do so before then. And Ezra 6:19–22 reports that the Israelites returned from the Babylonian captivity observed Passover, ate the Passover lamb, and kept the Feast of Unleavened Bread seven days with joy.

Shavuot

Exodus 23:16 refers to the Festival of Shavuot. In the Hebrew Bible, Shavuot is called:

- The Feast of Weeks (Hebrew: חַג שָׁבֻעֹת, Chag Shavuot);[77]

- The Day of the First-fruits (Hebrew: יוֹם הַבִּכּוּרִים, Yom haBikurim);[78]

- The Feast of Harvest (Hebrew: חַג הַקָּצִיר, Chag haKatzir);[79] and

- A holy convocation (Hebrew: מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh).[80]

Exodus 34:22 associates Shavuot with the first-fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרֵי, bikurei) of the wheat harvest.[81] In turn, Deuteronomy 26:1–11 set out the ceremony for the bringing of the first fruits.

To arrive at the correct date, Leviticus 23:15 instructs counting seven weeks from the day after the day of rest of Passover, the day that they brought the sheaf of barley for waving. Similarly, Deuteronomy 16:9 directs counting seven weeks from when they first put the sickle to the standing barley.

Leviticus 23:16–19 sets out a course of offerings for the fiftieth day, including a meal-offering of two loaves made from fine flour from the first-fruits of the harvest; burnt-offerings of seven lambs, one bullock, and two rams; a sin-offering of a goat; and a peace-offering of two lambs. Similarly, Numbers 28:26–30 sets out a course of offerings including a meal-offering; burnt-offerings of two bullocks, one ram, and seven lambs; and one goat to make atonement. Deuteronomy 16:10 directs a freewill-offering in relation to God's blessing.

Leviticus 23:21 and Numbers 28:26 ordain a holy convocation in which the Israelites were not to work.

2 Chronicles 8:13 reports that Solomon offered burnt-offerings on the Feast of Weeks.

Sukkot

And Exodus 23:16 refers to the Festival of Sukkot. In the Hebrew Bible, Sukkot is called:

- "The Feast of Tabernacles (or Booths)";Leviticus 23:34;Deuteronomy 16:13,31:10; Zechariah 14:16,Ezra 3:4;2 Chronicles 8:13.[82]

- "The Feast of Ingathering";[83]

- "The Feast" or "the festival";1 Kings 8:2,12:32;2 Chronicles 5:3;7:8.[84]

- "The Feast of the Lord";[85]

- "The festival of the seventh month";[86] and

- "A holy convocation" or "a sacred occasion."[87]

Sukkot's agricultural origin is evident from the name "The Feast of Ingathering," from the ceremonies accompanying it, and from the season and occasion of its celebration: "At the end of the year when you gather in your labors out of the field";[79] "after you have gathered in from your threshing-floor and from your winepress."[88] It was a thanksgiving for the fruit harvest.[89] And in what may explain the festival's name, Isaiah reports that grape harvesters kept booths in their vineyards.[90] Coming as it did at the completion of the harvest, Sukkot was regarded as a general thanksgiving for the bounty of nature in the year that had passed.

Sukkot became one of the most important feasts in Judaism, as indicated by its designation as "the Feast of the Lord"[91] or simply "the Feast."[84] Perhaps because of its wide attendance, Sukkot became the appropriate time for important state ceremonies. Moses instructed the children of Israel to gather for a reading of the Law during Sukkot every seventh year.[92] King Solomon dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem on Sukkot.[93] And Sukkot was the first sacred occasion observed after the resumption of sacrifices in Jerusalem after the Babylonian captivity.[94]

In the time of Nehemiah, after the Babylonian captivity, the Israelites celebrated Sukkot by making and dwelling in booths, a practice of which Nehemiah reports: "the Israelites had not done so from the days of Joshua."[95] In a practice related to that of the Four Species, Nehemiah also reports that the Israelites found in the Law the commandment that they "go out to the mountains and bring leafy branches of olive trees, pine trees, myrtles, palms and [other] leafy trees to make booths."[96] In Leviticus 23:40, God told Moses to command the people: "On the first day you shall take the product of hadar trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook," and "You shall live in booths seven days; all citizens in Israel shall live in booths, in order that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt."[97] The book of Numbers, however, indicates that while in the wilderness, the Israelites dwelt in tents.[98] Some scholars consider Leviticus 23:39–43 (the commandments regarding booths and the four species) to be an insertion by a late redactor.[99]

Jeroboam son of Nebat, King of the northern Kingdom of Israel, whom 1 Kings 13:33 describes as practicing "his evil way," celebrated a festival on the fifteenth day of the eighth month, one month after Sukkot, "in imitation of the festival in Judah."[100] "While Jeroboam was standing on the altar to present the offering, the man of God, at the command of the Lord, cried out against the altar" in disapproval.[101]

According to Zechariah, in the messianic era, Sukkot will become a universal festival, and all nations will make pilgrimages annually to Jerusalem to celebrate the feast there.[102]

Milk

In three separate places — Exodus 23:19 and 34:26 and Deuteronomy 14:21 — the Torah prohibits boiling a kid in its mother's milk.

Stone pillars

In Genesis 28:18, Jacob took the stone on which he had slept, set it up as a pillar (Hebrew: מַצֵּבָה, matzeivah), and poured oil on the top of it. Exodus 23:24 would later direct the Israelites to break in pieces the Canaanites' pillars (Hebrew: מַצֵּבֹתֵיהֶם, matzeivoteihem). Leviticus 26:1 would direct the Israelites not to rear up a pillar (Hebrew: מַצֵּבָה, matzeivah). And Deuteronomy 16:22 would prohibit them to set up a pillar (Hebrew: מַצֵּבָה, tzevahma), "which the Lord your God hates."

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[103]

Exodus chapter 22

The Damascus Document of the Qumran community prohibited non-cash transactions with Jews who were not members of the community. Professor Lawrence Schiffman of New York University read this regulation as an attempt to avoid violating prohibitions on charging interest to one's fellow Jew in Exodus 22:25; Leviticus 25:36–37; and Deuteronomy 23:19–20. Apparently, the Qumran community viewed prevailing methods of conducting business through credit to violate those laws.[104]

Exodus chapter 23

One of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Community Rule of the Qumran sectarians, cited Exodus 23:7, "Keep far from a deceitful matter," to support a prohibition of business partnerships with people outside of the group.[105]

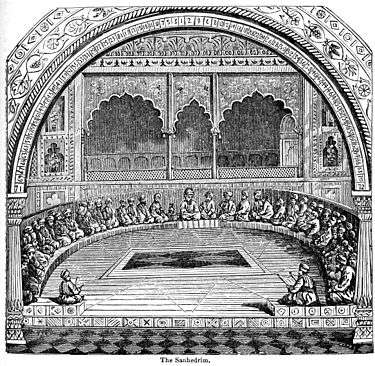

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[106]

Exodus chapter 21

Rabbi Akiva deduced from the words "now these are the ordinances that you shall put before them" in Exodus 21:1 that the teacher must wherever possible explain to the student the reasons behind the commandments.[107]

Part of chapter 1 of Tractate Kiddushin in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Hebrew servant in Exodus 21:2–11 and 21:26–27; Leviticus 25:39–55; and Deuteronomy 15:12–18.[108] The Mishnah taught that a Hebrew manservant (described in Exodus 21:2) was acquired by money or by contract, and could acquire his freedom by years of service, by the Jubilee year, or by deduction from the purchase price. The Mishnah taught that a Hebrew maidservant was more privileged in that she could acquire her freedom by signs of puberty. The servant whose ear was bored (as directed in Exodus 21:6) is acquired by boring his ear, and acquired his freedom by the Jubilee year or the master's death.[109]

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that the words of Deuteronomy 15:16 regarding the Hebrew servant, "he fares well with you," indicate that the Hebrew servant had to be "with" — that is, equal to — the master in food and drink. Thus the master could not eat white bread and have the servant eat black bread. The master could not drink old wine and have the servant drink new wine. The master could not sleep on a feather bed and have the servant sleep on straw. Hence, they said that buying a Hebrew servant was like buying a master. Similarly, Rabbi Simeon deduced from the words of Leviticus 25:41, "Then he shall go out from you, he and his children with him," that the master was liable to provide for the servant's children until the servant went out. And Rabbi Simeon deduced from the words of Exodus 21:3, "If he is married, then his wife shall go out with him," that the master was responsible to provide for the servant's wife, as well.[110]

Reading the words of Exodus 6:13, "And the Lord spoke to Moses and to Aaron, and gave them a command concerning the children of Israel," Rabbi Samuel bar Rabbi Isaac asked about what matter God commanded the Israelites. Rabbi Samuel bar Rabbi Isaac taught that God gave them the commandment about the freeing of slaves in Exodus 21:2–11.[111]

The Gemara read Exodus 21:4 to address a Hebrew slave who married the Master's Canaanite slave. The Gemara thus deduced from Exodus 21:4 that the children of such a marriage were also considered Canaanite slaves and thus that their lineage flowed from their mother, not their father. The Gemara used this analysis of Exodus 21:4 to explain why Mishnah Yevamot 2:5[112] taught that the son of a Canaanite slave mother does not impose the obligation of Levirite marriage (Hebrew: יִבּוּם, yibbum) under Deuteronomy 25:5–6.[113] Further interpreting Exodus 21:4, the Gemara noted that the Canaanite slave woman nonetheless had an obligation to observe certain commandments.[114]

Rabbi Eleazar reasoned that because Exodus 21:6 uses the term "ear" (in connection with the slave who refused to go out free) and Leviticus 14:14 also uses the term "ear" (in connection with the purification ritual for one with skin disease), just as Leviticus 14:14 explicitly requires using the right ear of the one to be cleansed, so Exodus 21:5 must also require using the slave's right ear.[115]

Reading Exodus 21:6, regarding the Hebrew servant who chose not to go free and whose master brought him to the doorpost and bore his ear through with an awl, Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai explained that God singled out the ear from all the parts of the body because the servant had heard God's Voice on Mount Sinai proclaiming in Leviticus 25:55, "For to me the children of Israel are servants, they are my servants," and not servants of servants, and yet the servant acquired a master for himself when he might have been free. Rabbi Simeon bar Rabbi explained that God singled out the doorpost from all other parts of the house because the doorpost was witness in Egypt when God passed over the lintel and the doorposts (as reported in Exodus 12) and proclaimed (in the words of Leviticus 25:55), "For to me the children of Israel are servants, they are my servants," and not servants of servants, and so God brought them forth from bondage to freedom, yet this servant acquired a master for himself.[116]

The Mishnah interpreted the language of Exodus 21:6 to teach that a man could sell his daughter, but a woman could not sell her daughter.[117]

Rabbi Eliezer interpreted the conjugal duty of Exodus 21:10 to require relations: for men of independence, every day; for laborers, twice a week; for donkey-drivers, once a week; for camel-drivers, once in 30 days; for sailors, once in six months.[118]

Chapter 2 of tractate Makkot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the cities of refuge in Exodus 21:12–14, Numbers 35:1–34, Deuteronomy 4:41–43, and 19:1–13.[119]

The Mishnah taught that those who killed in error went into banishment. One would go into banishment if, for example, while one was pushing a roller on a roof, the roller slipped over, fell, and killed someone. One would go into banishment if while one was lowering a cask, it fell down and killed someone. One would go into banishment if while coming down a ladder, one fell and killed someone. But one would not go into banishment if while pulling up the roller it fell back and killed someone, or while raising a bucket the rope snapped and the falling bucket killed someone, or while going up a ladder one fell down and killed someone. The Mishnah's general principle was that whenever the death occurred in the course of a downward movement, the culpable person went into banishment, but if the death did not occur in the course of a downward movement, the person did not go into banishment. If while chopping wood, the iron slipped from the ax handle and killed someone, Rabbi taught that the person did not go into banishment, but the sages said that the person did go into banishment. If from the split log rebounding killed someone, Rabbi said that the person went into banishment, but the sages said that the person did not go into banishment.[120]

Rabbi Jose bar Judah taught that to begin with, they sent a slayer to a city of refuge, whether the slayer killed intentionally or not. Then the court sent and brought the slayer back from the city of refuge. The Court executed whomever the court found guilty of a capital crime, and the court acquitted whomever the court found not guilty of a capital crime. The court restored to the city of refuge whomever the court found liable to banishment, as Numbers 35:25 ordained, "And the congregation shall restore him to the city of refuge from where he had fled."[121] Numbers 35:25 also says, "The manslayer . . . shall dwell therein until the death of the high priest, who was anointed with the holy oil," but the Mishnah taught that the death of a high priest who had been anointed with the holy anointing oil, the death of a high priest who had been consecrated by the many vestments, or the death of a high priest who had retired from his office each equally made possible the return of the slayer. Rabbi Judah said that the death of a priest who had been anointed for war also permitted the return of the slayer. Because of these laws, mothers of high priests would provide food and clothing for the slayers in cities of refuge so that the slayers might not pray for the high priest's death.[122] If the high priest died at the conclusion of the slayer's trial, the slayer did not go into banishment. If, however, the high priests died before the trial was concluded and another high priest was appointed in his stead and then the trial concluded, the slayer returned home after the new high priest's death.[123]

Rabbi Akiva cited Exodus 21:14, in which the duty to punish an intentional murderer takes precedence over the sanctity of the altar, to support the proposition that the avoidance of danger to human life takes precedence over the laws of the Sabbath. Thus, if a murderer came as priest to do the Temple service, one could take him away from the precincts of the altar. And Rabbah bar bar Hana taught in the name of Rabbi Johanan that to save life — for example, if a priest could testify to the innocence of a defendant — one could take a priest down from the altar even while he was performing the Temple service. Now if this is so, even where doubt existed whether there was any substance to the priest's testimony, yet one interrupted the Temple service, and the Temple service was important enough to suspend the Sabbath, how much more should the saving of human life suspend the Sabbath laws.[124]

Similarly, the Gemara reasoned that just as the Temple service — which was of high importance and superseded the Sabbath, as labor prohibited on the Sabbath could be performed in connection with the Temple service — could itself be superseded by the requirement to carry out a death sentence for murder, as Exodus 21:14 says, "You shall take him from My altar, that he may die," how much more reasonable is it that the Sabbath, which is superseded by the Temple service, should be superseded by the requirement to carry out a death sentence for murder?[125]

Noting that Exodus 21:17 commands, "He that curses his father or his mother shall surely be put to death," and Leviticus 24:15 commands, "Whoever curses his God shall bear his sin," the Rabbis taught in a Baraita that Scripture likens cursing parents to cursing God. As Exodus 20:11 (20:12 in NJSP) commands, "Honor your father and your mother," and Proverbs 3:9 directs, "Honor the Lord with your substance," Scripture likens the honor due to parents to that due to God. And as Leviticus 19:3 commands, "You shall fear your father and mother," and Deuteronomy 6:13 commands, "The Lord your God you shall fear and you shall serve," Scripture likens the fear of parents to the fear of God. But the Baraita conceded that with respect to striking (which Exodus 21:15 addresses with regard to parents), that it is certainly impossible (with respect to God). The Baraita concluded that these comparisons between parents and God are only logical, since the three (God, the mother, and the father) are partners in creation of the child. For the Rabbis taught in a Baraita that there are three partners in the creation of a person — God, the father, and the mother. When one honors one's father and mother, God considers it as if God had dwelt among them and they had honored God. And a Tanna taught before Rav Nachman that when one vexes one's father and mother, God considers it right not to dwell among them, for had God dwelt among them, they would have vexed God.[126]

Rav Aha taught that people have no power to bring about healing (and thus one should not practice medicine, but leave healing to God). But Abaye disagreed, as it was taught in the school of Rabbi Ishmael that the words of Exodus 21:19, "He shall cause him to be thoroughly healed," teach that the Torah gives permission for physicians to heal.[127]

The Gemara taught that the words "eye for eye" in Exodus 21:24 meant pecuniary compensation. Rabbi Simon ben Yohai asked those who would take the words literally how they would enforce equal justice where a blind man put out the eye of another man, or an amputee cut off the hand of another, or where a lame person broke the leg of another. The school of Rabbi Ishmael cited the words "so shall it be given to him" in Leviticus 24:20, and deduced that the word "give" could apply only to pecuniary compensation. The school of Rabbi Hiyya cited the words "hand for hand" in the parallel discussion in Deuteronomy 19:21 to mean that an article was given from hand to hand, namely money. Abaye reported that a sage of the school of Hezekiah taught that Exodus 21:23–24 said "eye for eye" and "life for life," but not "life and eye for eye," and it could sometimes happen that eye and life would be taken for an eye, as when the offender died while being blinded. Rav Papa said in the name of Rava (Abba ben Joseph bar Ḥama) that Exodus 21:19 referred explicitly to healing, and the verse would not make sense if one assumed that retaliation was meant. And Rav Ashi taught that the principle of pecuniary compensation could be derived from the analogous use of the term "for" in Exodus 21:24 in the expression "eye for eye" and in Exodus 21:36 in the expression "he shall surely pay ox for ox." As the latter case plainly indicated pecuniary compensation, so must the former.[128]

Tractate Bava Kamma in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of damages related to oxen in Exodus 21:28–32, 35–36, pits in Exodus 21:33–34, men who steal livestock in Exodus 21:37, crop-destroying beasts in Exodus 22:4, fires in Exodus 22:5, and related torts.[129] The Mishnah taught that Scripture deals with four principal causes of damage: (1) the ox (in Exodus 21:35–36), (2) the pit (in Exodus 21:33–34), (3) the crop-destroying beast (in Exodus 22:4), and (4) the fire (in Exodus 22:5). The Mishnah taught that although they differed in some respects, they had in common that they are in the habit of doing damage, and they have to be under their owner's control so that whenever one of them does damage, the owner is liable to indemnify with the best of the owner's estate (when money is not tendered).[130] The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that Scripture identifies three principal categories of damage by the ox: (1) by the horn (in Exodus 21:28), (2) by the tooth (in Exodus 22:4), and (3) by the foot (also in Exodus 22:4).[131]

Noting that Exodus 21:37 provides a penalty of five oxen for the theft of an ox but only four sheep for the theft of a sheep, Rabbi Meir deduced that the law attaches great importance to labor. For in the case of an ox, a thief interferes with the beast's labor, while in the case of a sheep, a thief does not disturb it from labor. Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai taught that the law attaches great importance to human dignity. For in the case of an ox, the thief can walk the animal away on its own feet, while in the case of a sheep, the thief usually has to carry it away, thus suffering indignity.[132]

Exodus chapter 22

Rabbi Ishmael cited Exodus 22:1, in which the right to defend one's home at night takes precedence over the prohibition of killing, to support the proposition that the avoidance of danger to human life takes precedence over the laws of the Sabbath. For in Exodus 22:1, in spite of all the other considerations, it is lawful to kill the thief. So even if in the case of the thief — where doubt exists whether the thief came to take money or life, and even though Numbers 35:34 teaches that the shedding of blood pollutes the land, so that the Divine Presence departs from Israel — yet it was lawful to save oneself at the cost of the thief's life, how much more may one suspend the laws of the Sabbath to save human life.[133]

The Mishnah interpreted the language of Exodus 22:2 to teach that a man was sold to make restitution for his theft, but a woman was not sold for her theft.[117]

Rabbi Ishmael and Rabbi Akiba differed over the meaning of the word "his" in the clause "of the best of his own field, and of the best of his own vineyard, shall he make restitution" in Exodus 22:4. Rabbi Ishmael read Exodus 22:4 to require the damager to compensate the injured party out of property equivalent to the injured party's best property, whereas Rabbi Akiba read Exodus 22:4 to require the damager to compensate the injured party out of the damager's best property. The Mishnah required that a damager compensates for damage done out of the damager's best quality property.[134] The Gemara explained that the Mishnah imposed this high penalty because Exodus 22:4 requires it, and Exodus 22:4 imposes this penalty to discourage the doing of damage.[135]

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani in the name of Rabbi Johanan interpreted the account of spreading fire in Exodus 22:5 as an application of the general principle that calamity comes upon the world only when there are wicked persons (represented by the thorns) in the world, and its effects always manifest themselves first upon the righteous (represented by the grain).[136]

Rabbi Isaac the smith interpreted Exodus 22:5 homiletically to teach that God has taken responsibility to rebuild the Temple, as God allowed the fire of man's sin to go out of Zion to destroy it, as Lamentations 4:11 reports, "He has kindled a fire in Zion, which has devoured the foundations thereof," and God will nonetheless rebuild them, as Zechariah 2:9 reports, "For I, says the Lord, will be to her a wall of fire round about, and I will be the glory in the midst of her."[137]

Chapter 3 and portions of the chapters 7 and 8 of Tractate Bava Metzia in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of bailment in Exodus 22:6–14.[138] The Mishnah identified four categories of guardians (shomrim): (1) an unpaid custodian (Exodus 22:6–8), (2) a borrower (Exodus 22:13–14a), (3) a paid custodian (Exodus 22:11), and (4) a renter (Exodus 22:14b). The Mishnah summarized the law when damage befell the property in question: An unpaid custodian must swear for everything and bears no liability, a borrower must pay in all cases, a paid custodian or a renter must swear concerning an animal that was injured, captured, or died, but must pay for loss or theft.[139]

Rabbah explained that the Torah in Exodus 22:8–10 requires those who admit to a part of a claim against them to take an oath, because the law presumes that no debtor is so brazen in the face of a creditor as to deny the debt entirely.[140]

Rabbi Haninah and Rabbi Johanan differed over whether sorcery like that in Exodus 22:17 had real power.[141]

Rabbi Eliezer the Great taught that the Torah warns against wronging a stranger (Hebrew: גֵר, ger) in 36, or others say 46, places (including Exodus 22:20 and 23:9).[142] The Gemara went on to cite Rabbi Nathan's interpretation of Exodus 22:20, "You shall neither wrong a stranger, nor oppress him; for you were strangers in the land of Egypt," to teach that one must not taunt one's neighbor about a flaw that one has oneself. The Gemara taught that thus a proverb says: If there is a case of hanging in a person's family history, do not say to the person, "Hang up this fish for me."[143]

Citing Exodus 22:20 to apply to verbal wrongs, the Mishnah taught that one must not say to a repentant sinner, "remember your former deeds," and one must not taunt a child of converts saying, "remember the deeds of your ancestors."[144] Similarly, a Baraita taught that one must not say to a convert who comes to study the Torah, "Shall the mouth that ate unclean and forbidden food, abominable and creeping things, come to study the Torah that was uttered by the mouth of Omnipotence!"[145]

The Gemara taught that the Torah provided similar injunctions in Exodus 22:25 and Deuteronomy 24:12–13 to teach that a lender had to return a garment worn during the day before sunrise, and return a garment worn during the night before sunset.[146]

Tractate Bekhorot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Talmud interpreted the laws of the firstborn in Exodus 13:1–2, 12–13; 22:28–29; and 34:19–20; and Numbers 3:13 and 8:17.[147] Elsewhere, the Mishnah drew from Exodus 13:13 that money in exchange for a firstborn donkey could be given to any Kohen;[148] that if a person weaves the hair of a firstborn donkey into a sack, the sack must be burned;[149] that they did not redeem with the firstborn of a donkey an animal that falls within both wild and domestic categories (a koy);[150] and that one was prohibited to derive benefit in any quantity at all from an unredeemed firstborn donkey.[151] And elsewhere, the Mishnah taught that before the Israelites constructed the Tabernacle, the firstborns performed sacrificial services, but after the Israelites constructed the Tabernacle, the Priests (Hebrew: כֹּהֲנִים, Kohanim) performed the services.[152]

Exodus chapter 23

In the Babylonian Talmud, the Gemara read Exodus 23:2, "You shall not follow a multitude to do evil," to support the rule that when a court tried a non-capital case, the decision of the majority of the judges determined the outcome.[153]

A Baraita taught that one day, Rabbi Eliezer employed every imaginable argument for the proposition that a particular type of oven was not susceptible to ritual impurity, but the Sages did not accept his arguments. Then Rabbi Eliezer told the Sages, "If the halachah agrees with me, then let this carob tree prove it," and the carob tree moved 100 cubits (and others say 400 cubits) out of its place. But the Sages said that no proof can be brought from a carob tree. Then Rabbi Eliezer told the Sages, "If the halachah agrees with me, let this stream of water prove it," and the stream of water flowed backwards. But the Sages said that no proof can be brought from a stream of water. Then Rabbi Eliezer told the Sages, "If the halachah agrees with me, let the walls of this house of study prove it," and the walls leaned over as if to fall. But Rabbi Joshua rebuked the walls, telling them not to interfere with scholars engaged in a halachic dispute. In honor of Rabbi Joshua, the walls did not fall, but in honor of Rabbi Eliezer, the walls did not stand upright, either. Then Rabbi Eliezer told the Sages, "If the halachah agrees with me, let Heaven prove it," and a Heavenly Voice cried out: "Why do you dispute with Rabbi Eliezer, for in all matters the halachah agrees with him!" But Rabbi Joshua rose and exclaimed in the words of Deuteronomy 30:12: "It is not in heaven." Rabbi Jeremiah explained that God had given the Torah at Mount Sinai; Jews pay no attention to Heavenly Voices, for God wrote in Exodus 23:2: "After the majority must one incline." Later, Rabbi Nathan met Elijah and asked him what God did when Rabbi Joshua rose in opposition to the Heavenly Voice. Elijah replied that God laughed with joy, saying, "My children have defeated Me, My children have defeated Me!"[154]

Rav Aḥa bar Pappa cited Exodus 23:2, "Neither shall you answer in a cause (Hebrew: רִב, riv)," to support the rule of Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:2[155] that in capital cases, the judges began issuing their opinions from the side, where the least significant judges sat. The Sages interpreted Exodus 23:2 to read, "Neither shall you answer after the Master (Hebrew: רַב, rav), that is: Do not dispute the opinion of the greatest among the judges. Were the judges to begin issuing their opinions from the greatest to the least among the judges, and the greatest would find the accused guilty, no judge would acquit the accused. Thus to encourage the lesser judges to speak freely in capital cases, the Mishnah's rule had them speak first.[156]

The Mishnah read the emphatic words of Exodus 23:5, "you shall surely release it," repeating the verb in the Hebrew, to teach that Exodus 23:5 required a passer-by to unload an enemy's animal to let it get up and to reload the animal. And even if the passer-by repeated the process four or five times, the passer-by was still bound to do it again, because Exodus 23:5 says, "you shall surely help." If the owner of the animal simply sat down and said to the passer-by that the obligation rested upon the passer-by to unload, then the passer-by was exempt, because Exodus 23:5 says, "with him." Yet if the animal's owner was old or infirm, the passer-by was bound to do it without the owner's help. The Mishnah taught that Exodus 23:5 required the passer-by to unload the animal, but not to reload it. But Rabbi Simeon said that Exodus 23:5 required the passer-by to load it too. Rabbi Jose the Galilean said that if the animal bore more than its proper burden, then the passer-by had no obligation towards the owner, because Exodus 23:5 says, "If you see the donkey of him who hates you lying under its burden," which means, a burden under which it can stand.[157]

Rav Aḥa bar Pappa read Exodus 23:6, "You shall not incline the judgment of your poor in his cause," to teach that a court could not convict one accused of a capital crime (the "poor" person to whom Rav Aḥa read the verse to refer) by just a simple one-vote majority. Rav Aḥa's thus read Exodus 23:6 to make it harder for a court to convict one accused of a capital crime.[158]

The Mishnah interpreted Exodus 23:8 to teach that judges who accept bribes and change their judgments on account of the bribe will not die of old age before their eyes grow weak.[159]

A Baraita reasoned that Exodus 23:8, "And you shall take no bribe," cannot teach merely that one should not acquit the guilty nor convict the innocent due to a bribe, for Deuteronomy 16:19 already says, "You shall not wrest judgment." Rather, Exodus 23:8 teaches that even if a bribe is given to ensure that a judge acquit the innocent and convict the guilty, Exodus 23:8 nevertheless says, "And you shall take no bribe." Thus it is prohibited for a judge to receive anything from litigants, even if there is no concern at all that justice will be perverted.[160]

Rava taught that the reason for the prohibition against taking a bribe is that once a judge accepts a bribe from a party, the judge's thoughts draw closer to the party and the party becomes like the judge's own self, and one does not find fault with oneself. The Gemara noted that the term "bribe" (Hebrew: שֹּׁחַד, shochad) alludes to this idea, as it can be read as "as he is one" (shehu chad), that is, the judge is at one mind with the litigant. Rav Papa taught that judges should not judge cases involving those whom the judge loves (as the judge will not find any fault in them), nor involving those whom the judge hates (as the judge will not find any merit in them).[161]

The Sages taught that it is not necessary to say that Exodus 23:8 precludes bribery by means of money, and even verbal bribery is also prohibited. The law that a bribe is not necessarily monetary was be derived from the fact that Exodus 23:8 does not say: "And you shall take no profit." The Gemara illustrated this by telling how Samuel was once crossing a river on a ferry and a certain man gave him a hand to help him out of the ferryboat. Samuel asked him what he was doing in the place, and when the man told Samuel that he had a case to present before Samuel, Samuel told him that he was disqualified from presiding over the case, as the man did Samuel a favor, and although no money changed hands, a bond had been formed between them. Similarly, the Gemara told that Ameimar disqualified himself from presiding over the case of a person who removed a feather from Ameimar's head, and Mar Ukva disqualified himself from presiding over the case of a person who covered spittle that was lying before Mar Ukva.[162]

A Midrash read Exodus 23:9 to says, "And a convert shall you not oppress," and read it together with Psalm 146:8–9, which the Midrash read as, "The Lord loves the righteous; the Lord preserves the converts." The Midrash taught that God loves those who love God, and thus God loves the righteous, because their worth is due neither to heritage nor to family. The Midrash compared God's great love of converts to a king who had a flock of goats, and once a stag came in with the flock. When the king was told that the stag had joined the flock, the king felt an affection for the stag and gave orders that the stag have good pasture and drink and that no one beat him. When the king's servants asked him why he protected the stag, the king explained that the flock have no choice, but the stag did. The king accounted it as a merit to the stag that had left behind the whole of the broad, vast wilderness, the abode of all the beasts, and had come to stay in the courtyard. In like manner, God provided converts with special protection, for God exhorted Israel not to harm them, as Deuteronomy 10:19 says, "Love therefore the convert," and Exodus 23:9 says, "And a convert shall you not oppress."[163]

Tractate Sheviit in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of the Sabbatical year in Exodus 23:10–11, Leviticus 25:1–34, and Deuteronomy 15:1–18 and 31:10–13.[164] The Mishnah asked until when a field with trees could be plowed in the sixth year. The House of Shammai said as long as such work would benefit fruit that would ripen in the sixth year. But the House of Hillel said until Shavuot. The Mishnah observed that in reality, the views of two schools approximate each other.[165] The Mishnah taught that one could plow a grain-field in the sixth year until the moisture had dried up in the soil (that it, after Passover, when rains in the Land of Israel cease) or as long as people still plowed in order to plant cucumbers and gourds (which need a great deal of moisture). Rabbi Simeon objected that if that were the rule, then we would place the law in the hands of each person to decide. But the Mishnah concluded that the prescribed period in the case of a grain-field was until Passover, and in the case of a field with trees, until Shavuot.[166] But Rabban Gamaliel and his court ordained that working the land was permitted until the New Year that began the seventh year.[167] Rabbi Johanan said that Rabban Gamaliel and his court reached their conclusion on Biblical authority, noting the common use of the term "Sabbath" (Hebrew: שַׁבַּת, Shabbat) in both the description of the weekly Sabbath in Exodus 31:15 and the Sabbath-year in Leviticus 25:4. Thus, just as in the case of the Sabbath Day, work is forbidden on the day itself, but allowed on the day before and the day after, so likewise in the Sabbath Year, tillage is forbidden during the year itself, but allowed in the year before and the year after.[168]

The Mishnah taught that exile resulted from (among other things) transgressing the commandment (in Exodus 23:10–11 and Leviticus 25:3–5) to observe a Sabbatical year for the land.[169] Rabbi Isaac taught that the words of Psalm 103:20, "mighty in strength that fulfill His word," speak of those who observe the Sabbatical year. Rabbi Isaac said that we often find that a person fulfills a precept for a day, a week, or a month, but it is remarkable to find one who does so for an entire year. Rabbi Isaac asked whether one could find a mightier person than one who sees his field untilled, see his vineyard untilled, and yet pays his taxes and does not complain. And Rabbi Isaac noted that Psalm 103:20 uses the words "that fulfill His word (Hebrew: דְּבָרוֹ, devaro)," and Deuteronomy 15:2 says regarding observance of the Sabbatical year, "And this is the manner (Hebrew: דְּבַר, devar) of the release," and argued that Hebrew: דְּבַר, devar means the observance of the Sabbatical year in both places.[170]

Tractate Shabbat in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Sabbath in Exodus 16:23 and 29; 20:7–10 (20:8–11 in the NJPS); 23:12; 31:13–17; 35:2–3; Leviticus 19:3; 23:3; Numbers 15:32–36; and Deuteronomy 5:11 (5:12 in the NJPS).[171]

A Midrash asked to which commandment Deuteronomy 11:22 refers when it says, "For if you shall diligently keep all this commandment that I command you, to do it, to love the Lord your God, to walk in all His ways, and to cleave to Him, then will the Lord drive out all these nations from before you, and you shall dispossess nations greater and mightier than yourselves." Rabbi Levi said that "this commandment" refers to the recitation of the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4–9), but the Rabbis said that it refers to the Sabbath, which is equal to all the precepts of the Torah.[172]

The Alphabet of Rabbi Akiva taught that when God was giving Israel the Torah, God told them that if they accepted the Torah and observed God's commandments, then God would give them for eternity a most precious thing that God possessed — the World To Come. When Israel asked to see in this world an example of the World To Come, God replied that the Sabbath is an example of the World To Come.[173]

The Gemara deduced from the parallel use of the word "appear" in Exodus 23:14 and Deuteronomy 16:15 (regarding appearance offerings) on the one hand, and in Deuteronomy 31:10–12 (regarding the great assembly) on the other hand, that the criteria for who participated in the great assembly also applied to limit who needed to bring appearance offerings. A Baraita deduced from the words "that they may hear" in Deuteronomy 31:12 that a deaf person was not required to appear at the assembly. And the Baraita deduced from the words "that they may learn" in Deuteronomy 31:12 that a mute person was not required to appear at the assembly. But the Gemara questioned the conclusion that one who cannot talk cannot learn, recounting the story of two mute grandsons (or others say nephews) of Rabbi Johanan ben Gudgada who lived in Rabbi's neighborhood. Rabbi prayed for them, and they were healed. And it turned out that notwithstanding their speech impediment, they had learned halachah, Sifra, Sifre, and the whole Talmud. Mar Zutra and Rav Ashi read the words "that they may learn" in Deuteronomy 31:12 to mean "that they may teach," and thus to exclude people who could not speak from the obligation to appear at the assembly. Rabbi Tanhum deduced from the words "in their ears" (using the plural for "ears") at the end of Deuteronomy 31:11 that one who was deaf in one ear was exempt from appearing at the assembly.[174]

Tractate Beitzah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws common to all of the Festivals in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:16; 34:18–23; Leviticus 16; 23:4–43; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–30:1; and Deuteronomy 16:1–17; 31:10–13.[175]

Tractate Pesachim in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Passover in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:15; 34:25; Leviticus 23:4–8; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–25; and Deuteronomy 16:1–8.[176]

The Mishnah noted differences between the first Passover in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:15; 34:25; Leviticus 23:4–8; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–25; and Deuteronomy 16:1–8. and the second Passover in Numbers 9:9–13. The Mishnah taught that the prohibitions of Exodus 12:19 that "seven days shall there be no leaven found in your houses" and of Exodus 13:7 that "no leaven shall be seen in all your territory" applied to the first Passover; while at the second Passover, one could have both leavened and unleavened bread in one's house. And the Mishnah taught that for the first Passover, one was required to recite the Hallel (Psalms 113–118) when the Passover lamb was eaten; while the second Passover did not require the reciting of Hallel when the Passover lamb was eaten. But both the first and second Passovers required the reciting of Hallel when the Passover lambs were offered, and both Passover lambs were eaten roasted with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. And both the first and second Passovers took precedence over the Sabbath.[177]

The Gemara noted that in listing the several Festivals in Exodus 23:15, Leviticus 23:5, Numbers 28:16, and Deuteronomy 16:1, the Torah always begins with Passover.[178]

The Gemara cited Exodus 23:15 to support the proposition, which both Resh Lakish and Rabbi Johanan held, that on the mid-festival days (Chol HaMoed) it is forbidden to work. For the Rabbis taught in a Baraita the view of Rabbi Josiah that because the word "keep" is read to imply prohibition of work, the words, "The Feast of Unleavened Bread shall you keep, seven days," in Exodus 23:15 teach that work is forbidden for seven days, and thus work is forbidden on the mid-festival days.[179]

According to one version of the dispute, Resh Lakish and Rabbi Johanan disagreed over how to interpret the words, "None shall appear before Me empty," in Exodus 23:15. Resh Lakish argued that Exodus 23:15 taught that whenever a pilgrim appeared at the Temple, even during the succeeding days of a multi-day Festival, the pilgrim had to bring an offering. But Rabbi Johanan argued that Exodus 23:15 refers to only the first day of a Festival, and not to succeeding days. After relating this dispute, the Gemara reconsidered and concluded that Resh Lakish and Rabbi Johanan differed not over whether additional offerings were obligatory, but over whether additional offerings were permitted.[180]

Tractate Sukkah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of Sukkot in Exodus 23:16; 34:22; Leviticus 23:33–43; Numbers 29:12–34; and Deuteronomy 16:13–17; 31:10–13.[181]

The Mishnah taught that a sukkah can be no more than 20 cubits high. Rabbi Judah, however, declared taller sukkot valid. The Mishnah taught that a sukkah must be at least 10 handbreadths high, have three walls, and have more shade than sun.[182] The House of Shammai declared invalid a sukkah made 30 days or more before the festival, but the House of Hillel pronounced it valid. The Mishnah taught that if one made the sukkah for the purpose of the festival, even at the beginning of the year, it is valid.[183]

The Mishnah taught that a sukkah under a tree is as invalid as a sukkah within a house. If one sukkah is erected above another, the upper one is valid, but the lower is invalid. Rabbi Judah said that if there are no occupants in the upper one, then the lower one is valid.[184]

It invalidates a sukkah to spread a sheet over the sukkah because of the sun, or beneath it because of falling leaves, or over the frame of a four-post bed. One may spread a sheet, however, over the frame of a two-post bed.[185]

It is not valid to train a vine, gourd, or ivy to cover a sukkah and then cover it with sukkah covering (s'chach). If, however, the sukkah-covering exceeds the vine, gourd, or ivy in quantity, or if the vine, gourd, or ivy is detached, it is valid. The general rule is that one may not use for sukkah-covering anything that is susceptible to ritual impurity (tumah) or that does not grow from the soil. But one may use for sukkah-covering anything not susceptible to ritual impurity that grows from the soil.[186]

Bundles of straw, wood, or brushwood may not serve as sukkah-covering. But any of them, if they are untied, are valid. All materials are valid for the walls.[187]

Rabbi Judah taught that one may use planks for the sukkah-covering, but Rabbi Meir taught that one may not. The Mishnah taught that it is valid to place a plank four handbreadths wide over the sukkah, provided that one does not sleep under it.[188]

The Mishnah deduced from the words "the feast of harvest, the first-fruits of your labors, which you sow in the field" in Exodus 23:16 that first fruits were not to be brought before Shavuot. The Mishnah reported that the men of Mount Zeboim brought their first fruits before Shavuot, but the priests did not accept them, because of what is written in Exodus 23:16.[189]

Tractate Bikkurim in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of the first fruits in Exodus 23:19, Numbers 18:13, and Deuteronomy 12:17–18 and 26:1–11.[190] The Mishnah interpreted the words "the first-fruits of your land" in Exodus 23:19 to mean that a person could not bring first fruits unless all the produce came from that person's land. The Mishnah thus taught that people who planted trees but bent their branches into or over another's property could not bring first fruits from those trees. And for the same reason, the Mishnah taught that tenants, lessees, occupiers of confiscated property, or robbers could not bring first fruits.[191]

The Mishnah taught that they buried meat that had mixed with milk in violation of Exodus 23:19 and 34:26 and Deuteronomy 14:21.[192]

Rav Nachman taught that the angel of whom God spoke in Exodus 23:20 was Metatron (Hebrew: מטטרון). Rav Nahman warned that one who is as skilled in refuting heretics as Rav Idit should do so, but others should not. Once a heretic asked Rav Idit why Exodus 24:1 says, "And to Moses He said, 'Come up to the Lord,'" when surely God should have said, "Come up to Me." Rav Idit replied that it was the angel Metatron who said that, and that Metatron's name is similar to that of his Master (and indeed the gematria (numerical value of the Hebrew letters) of Metatron (Hebrew: מטטרון) equals that of Shadai (Hebrew: שַׁדַּי), God's name in Genesis 17:1 and elsewhere) for Exodus 23:21 says, "for my name is in him." But if so, the heretic retorted, we should worship Metatron. Rav Idit replied that Exodus 23:21 also says, "Be not rebellious against him," by which God meant, "Do not exchange Me for him" (as the word for "rebel," (Hebrew: תַּמֵּר, tameir) derives from the same root as the word "exchange"). The heretic then asked why then Exodus 23:21 says, "he will not pardon your transgression." Rav Idit answered that indeed Metatron has no authority to forgive sins, and the Israelites would not accept him even as a messenger, for Exodus 33:15 reports that Moses told God, "If Your Presence does not go with me, do not carry us up from here."[193]

The Midrash Tanhuma taught that the words "the place which I have prepared" in Exodus 23:20 indicate that the Temple in Jerusalem is directly opposite the Temple in Heaven.[194]

The Gemara interpreted the words of Moses, "I am 120 years old this day," in Deuteronomy 31:2 to signify that Moses spoke on his birthday, and that he thus died on his birthday. Citing the words "the number of your days I will fulfill" in Exodus 23:26, the Gemara concluded that God completes the years of the righteous to the day, concluding their lives on their birthdays.[195]

The Gemara reported a dispute over the meaning of Exodus 23:26. Rava taught that King Manasseh of Judah tried and executed Isaiah, charging Isaiah with false prophesy based, among other things, on a contradiction between Exodus 23:26 and Isaiah's teachings. Manasseh argued that when (as reported in Exodus 23:26) Moses quoted God saying, "The number of your days I will fulfill," God meant that God would allow people to live out their appointed lifespan, but not add to it. But Manasseh noted that Isaiah told Manasseh's father Hezekiah (as reported in 2 Kings 20:5–6) that God promised Hezekiah, "I will add on to your days fifteen years." According to Rava, Isaiah did not dispute Manasseh's charges, knowing that Manasseh would not accept Isaiah's argument, no matter how truthful, and Manasseh had Isaiah killed. The Gemara reported that the Tannaim disagreed about the interpretation of the words "the number of your days I will fulfill" in Exodus 23:26. A Baraita taught that "the number of your days I will fulfill" refers to the lifespan that God allots to every human being at birth. Rabbi Akiba taught that if one is worthy, God allows one to complete the full period; if unworthy, God reduces the number of years. The Sages, however, taught that if one is worthy, God adds years to one's life; if one is unworthy, God reduces the years. The Sages argued to Rabbi Akiba that Isaiah's prophesy to Hezekiah in 2 Kings 20:5–6, "And I will add to your days fifteen years," supports the Sages' interpretation. Rabbi Akiba replied that God made the addition to Hezekiah's lifespan from years that God had originally intended for Hezekiah that Hezekiah had previously lost due to sin. Rabbi Akiba cited in support of his position the words of the prophet in the days of Jeroboam, before the birth of Hezekiah, who prophesied (as reported in 1 Kings 13:2), "a son shall be born to the house of David, Josiah by name." Rabbi Akiba argued that since the prophet prophesied the birth of Manasseh's son Josiah before the birth of Manasseh's father Hezekiah, it must be that at Hezekiah's birth God had allotted to Hezekiah enough years to extend beyond the time of Hezekiah's illness (when Isaiah prophesied in 2 Kings 20:5–6) so as to include the year of Manasseh's birth. Consequently, Rabbi Akiba argued, at the time of Hezekiah's illness, God must have reduced the original number of years allotted to Hezekiah, and upon Hezekiah's recovery, God must have added back only that which God had previously reduced. The Rabbis, however, argued back that the prophet in the days of Jeroboam who prophesied in 1 Kings 13:2 did not prophesy that Josiah would necessarily descend from Hezekiah. The prophet prophesied in 1 Kings 13:2 that Josiah would be born "to the house of David." Thus Josiah might have descended either from Hezekiah or from some other person in the Davidic line.[196]

A Baraita taught that the words, "I will send My terror before you, and will discomfort all the people to whom you shall come, and I will make all your enemies turn their backs to you," in Exodus 23:27, and the words, "Terror and dread fall upon them," in Exodus 15:16 show that no creature was able to withstand the Israelites as they entered into the Promised Land in the days of Joshua, and those who stood against them were immediately panic-stricken and lost control of their bowels. And the words, "till Your people pass over, O Lord," in Exodus 15:16 allude to the first advance of the Israelites into the Promised Land in the days of Joshua. And the words, "till the people pass over whom You have gotten," in Exodus 15:16 allude to the second advance of the Israelites into the Promised Land in the days of Ezra. The Baraita thus concluded that the Israelites were worthy that God should perform a miracle on their behalf during the second advance as in the first advance, but that did not happen because the Israelites' sin caused God to withhold the miracle.[197]

In Exodus 23:28, God promised to "send the hornet (Hebrew: צִּרְעָה, tzirah) before you, which shall drive out the Hivite, the Canaanite, and the Hittite, from before you," and in Deuteronomy 7:20, Moses promised that "the Lord your God will send the hornet (Hebrew: צִּרְעָה, tzirah) among them." But a Baraita taught that the hornet did not pass over the Jordan River with the Israelites. Rabbi Simeon ben Lakish reconciled the two sources, explaining that the hornet stood on the eastern bank of the Jordan and shot its venom over the river at the Canaanites. The venom blinded the Canaanites' eyes above and castrated them below, as Amos 2:9 says, "Yet destroyed I the Amorite before them, whose height was like the height of the cedars, and he was strong as the oaks; yet I destroyed his fruit from above and his roots from beneath." Rav Papa offered an alternative explanation, saying that there were two hornets, one in the time of Moses and the other in the time of Joshua. The former did not pass over the Jordan, but the latter did.[198]

Exodus chapter 24

Rav Huna son of Rav Kattina sat before Rav Chisda, and Rav Chisda cited Exodus 24:5, "And he sent the young men of the children of Israel, who offered burnt-offerings, and sacrificed peace-offerings of oxen to the Lord," as an application of the proposition stated in the Mishnah that "before the Tabernacle was set up . . . the service was performed by the firstborn; after the tabernacle was set up . . . the service was performed by priests."[199] (The "young men" in Exodus 24:5 were the firstborn, not priests.) Rav Huna replied to Rav Chisda that Rabbi Assi taught that after that the firstborn ceased performing the sacrificial service (even though it was nearly a year before the Tabernacle was set up).[200]

It was taught in a Baraita that King Ptolemy brought together 72 elders and placed them in 72 separate rooms, without telling them why he had brought them together, and asked each of them to translate the Torah. God then prompted each of them to conceive the same idea and write a number of cases in which the translation did not follow the Masoretic Text, including, for Exodus 24:5, "And he sent the elect of the children of Israel" — writing "elect" instead of "young men"; and for Exodus 24:11, "And against the elect of the children of Israel he put not forth his hand" — writing "elect" instead of "nobles."[201]

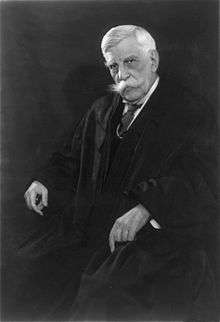

.jpg)

Rabbi Isaac taught that when a king administers an oath to his legions, he does so with a sword, implying that whoever transgressed the oath would have the sword pass over his neck. Similarly, at Sinai, as Exodus 24:6 reports, "Moses took half of the blood" (thus adjuring them with the blood). The Midrash asked how Moses knew how much was half of the blood. Rabbi Judah bar Ila'i taught that the blood divided itself into halves on its own. Rabbi Nathan said that its appearance changed; half of it turned black, and half remained red. Bar Kappara told that an angel in the likeness of Moses came down and divided it. Rabbi Isaac taught that a Heavenly Voice came from Mount Horeb, saying that this much is half of the blood. Rabbi Ishmael taught in a Baraita that Moses was expert in the regulations relating to blood, and by means of that knowledge divided it. Exodus 24:6 goes on to say, "And he put it in basins (Hebrew: אַגָּנֹת, aganot)." Rav Huna said in the name of Rabbi Avin that Exodus 24:6 writes the word in a form that might be read aganat ("basin," singular) indicating that neither basin was larger than the other. Moses asked God what to do with God's portion. God told Moses to sprinkle it on the people. (Exodus 24:8 reports, "And Moses took the blood, and sprinkled it on the people.") Moses asked what he should do with the Israelites' portion. God said to sprinkle it on the altar, as Exodus 24:6 says, "And half of the blood he dashed against the altar."[202]

Reading Exodus 24:7 "And he took the book of the covenant, and read in the hearing of the people," the Mekhilta asked what Moses had read. Rabbi Jose the son of Rabbi Judah said that Moses read from the beginning of Genesis up to Exodus 24:7. Rabbi said that Moses read to them the laws commanded to Adam, the commandments given to the Israelites in Egypt and at Marah, and all other commandments that they had already been given. Rabbi Ishmael said that Moses read to them the laws of the sabbatical years and the jubilees [in Leviticus 25] and the blessings and the curses in Leviticus 26, as it says at the end of that section (in Leviticus 26:46), "These are the statutes and ordinances and laws." The Israelites said that they accepted all those.[203]

.jpg)

Reading the words of Exodus 24:7, "will we do, and hear" the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that God asked the Israelites whether they would receive for themselves the Torah. Even before they had heard the Torah, they answered God that they would keep and observe all the precepts that are in the Torah, as Exodus 24:7 reports, "And they said, 'All that the Lord has spoken will we do, and be obedient.'"[204]

Rabbi Phineas taught that it was on the eve of the Sabbath that the Israelites stood at Mount Sinai, arranged with the men apart and the women apart. God told Moses to ask the women whether they wished to receive the Torah. Moses asked the women first, because the way of men is to follow the opinion of women, as Exodus 19:3 reflects when it says, "Thus shall you say to the house of Jacob" — these are the women — and only thereafter does Exodus 19:3 say, "And tell the children of Israel" — these are the men. They all replied as with one voice, in the words of Exodus 24:7, "All that the Lord has spoken we will do, and be obedient."[205]

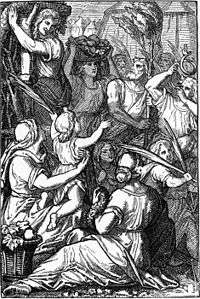

Reading the words of Exodus 24:7, "will we do, and hear" Rabbi Simlai taught that when the Israelites gave precedence to "we will do" over "we will hear" (promising to obey God's commands even before hearing them), 600,000 ministering angels came and set two crowns on each Israelite man, one as a reward for "we will do" and the other as a reward for "we will hear." But as soon as the Israelites committed the sin of the Golden Calf, 1.2 million destroying angels descended and removed the crowns, as it is said in Exodus 33:6, "And the children of Israel stripped themselves of their ornaments from mount Horeb."[206]