Mike Patton

Michael Allan Patton (born January 27, 1968) is an American singer, producer, voice actor and film composer, best known as the lead vocalist of the alternative metal band Faith No More.[9] Noted for his vocal proficiency, diverse singing techniques, wide range of projects, style-transcending influences and eccentric public image, Patton has earned critical praise and influenced many contemporary singers. Patton is also co-founder and lead vocalist of Mr. Bungle, and has played with Tomahawk, Fantômas, Dead Cross, Lovage, The Dillinger Escape Plan, Mondo Cane, and Peeping Tom.

Mike Patton | |

|---|---|

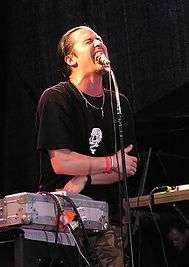

Patton in 2009 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Michael Allan Patton |

| Born | January 27, 1968 Eureka, California, US |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments | Vocals |

| Years active | 1984–present |

| Labels | |

| Associated acts | |

VVN Music found Patton possesses the widest vocal range of any known singer in popular music, with a range of six octaves.[10] He has worked as a producer or co-producer with artists such as John Zorn, Sepultura, Melvins, Melt-Banana, and Kool Keith. He co-founded Ipecac Recordings with Greg Werckman in 1999, and has run the label since. Patton's vast number of musical endeavours and constant touring have led to him being widely identified as a "workaholic".

Early years

—Mike Patton, 2005[11]

Patton was born in Eureka, California to a social worker mother and a PE teacher father.[11][12] He is part Native American.[13] Patton's home was strictly secular.[14] He described himself as "restless" growing up and looked for different ways to spend time in Eureka,[11] a relatively isolated city in the far north of California (being the biggest town between San Francisco and Portland, and surrounded by dense redwood forests).[15]

Patton studied at Eureka High School where he met bassist Trevor Dunn and afterward guitarist Trey Spruance, both members of its music theory class and jazz ensembles.[15] Dunn and Patton formed part of the cover band Gemini that performed songs by popular heavy metal acts.[16] They quickly gained an interest in heavier styles and joined the thrash metal cover group Fiend, but were later kicked out and subsequently recorded a death metal tape under the name Turd with Dunn on vocals and Patton on the instruments. Simultaneously, Spruance, who is a year younger, and drummer Jed Watts were members of Torchure, a Mercyful Fate-inspired band that had played with Fiend, and they went on to form another two-piece extreme metal band called FCA. Eventually, the four musicians decided to join up and established Mr. Bungle in 1985.[17][18] Its members often engaged in late night freighthopping as a way to pass the time in Eureka. They would get off at nearby towns or remote, wooded areas, relying on hitchhiking to find their way home.[15] According to Spruance, they were drawn to dissident music because of the "alien isolation" of Eureka, in particular their dissatisfaction with its rural, uptight Christian culture and "rough" idiosyncrasy.[15]

Patton enrolled in Humboldt State University, located in the nearby town of Arcata, to study English literature.[19][20] At Humboldt, Patton first met his future band Faith No More during a 1986 show at a pizza parlor, where Mr. Bungle played numerous times. After the performance, Spruance, who had invited Patton to the show, gave drummer Mike Bordin Mr. Bungle's first demo The Raging Wrath of the Easter Bunny.[21][19] From school to college, Patton also worked part-time at the only record store in Eureka until he joined Faith No More in 1988.[22][23][19]

During the late 1980s Mr. Bungle released a number of demos on cassette only: 1986's The Raging Wrath of the Easter Bunny, 1987's Bowel of Chiley, 1988's Goddammit I Love America and 1989's OU818. The last three feature tracks that would later be included on their 1991 debut studio release.[24]

Music career

Faith No More: 1988–1998; 2009–present

After the members of Faith No More heard Mr. Bungle's second demo tape in 1987, they approached Patton to audition as their lead singer in 1988.[21] In January 1989, Patton officially replaced Chuck Mosley as vocalist and forced him to quit his studies at Humboldt State University.[19][25] Mosley subsequently formed the bands Cement and VUA, and had several special "one-off" performances at shows with Faith No More and Patton before his death in 2017.[26][27]

Faith No More's The Real Thing was released in 1989. The album reached the top ten on the US charts, thanks largely to MTV's heavy rotation of the "Epic" music video, (which features Patton in a Mr. Bungle T-shirt).[28] Faith No More released three more studio albums—Angel Dust, King for a Day... Fool for a Lifetime, and Album of the Year—before disbanding in 1998. In several interviews, Patton cited the declining quality of the band's work as a contributing factor to the split.[29][30]

On February 24, 2009, after months of speculation and rumors, Faith No More announced they would be reforming with a line-up identical to the Album of the Year era, embarking on a reunion tour called The Second Coming Tour.[31] To coincide with the band's reunion tour, Rhino released the sixth Faith No More compilation, The Very Best Definitive Ultimate Greatest Hits Collection in the UK on June 8.[32] The same line-up eventually released a new album called Sol Invictus in 2015.

When interviewed about his lyrical content with Faith No More, Patton responded, "I think that too many people think too much about my lyrics. I am more a person who works more with the sound of a word than with its meaning. Often I just choose the words because of the rhythm, not because of the meaning".[33]

Solo work and band projects: 1984–present

During his time in Faith No More, Patton continued to work with Mr. Bungle. His success in mainstream rock and metal ultimately helped secure Mr. Bungle a record deal with Warner Bros.[34] The band released a self-titled album (produced by John Zorn) in 1991, and the experimental Disco Volante[35] in 1995. Their final album, California, was released in 1999. The band ceased being active following the 1999–2000 tour in support of the California record, although their disbandment was only officially confirmed in November 2004. Patton explained to Rolling Stone: "I'm at a point now where I crave healthy musical environments, where there is a genuine exchange of ideas without repressed envy or resentment, and where people in the band want to be there regardless of what public accolades may come their way. Unfortunately, Mr. Bungle was not one of those places."[36]

Patton's other projects included two solo albums on the Composer Series of John Zorn's Tzadik label, (Adult Themes for Voice in 1996 and Pranzo Oltranzista in 1997). He is a member of Hemophiliac, in which he performs vocal effects along with John Zorn on saxophone and Ikue Mori on laptop electronics. This group is billed as "improvisational music from the outer reaches of madness".[37] He has also guested on Painkiller and Naked City recordings. He has appeared on other Tzadik releases with Zorn and others, notably as part of the "Moonchild Trio" alongside Joey Baron and Trevor Dunn, named after Zorn's album on which the trio first appeared, Moonchild: Songs Without Words.

In 1998, Patton formed the metal supergroup Fantômas with Buzz Osborne (of The Melvins), Trevor Dunn (of Mr. Bungle), and Dave Lombardo (of Slayer). They have released four studio albums.

In 1999, Patton met former The Jesus Lizard guitarist Duane Denison at a Mr. Bungle concert in Nashville, and the two subsequently formed the band Tomahawk.[38] Tomahawk's straightforward rock sound has often been compared to Album of the Year/King for a Day era Faith No More.[39][40]

In 2001, he contributed vocals to Chino Moreno's group Team Sleep[41] and released the album Music to Make Love to Your Old Lady By with the group Lovage, a collaborative project consisting of Patton, Dan the Automator, Jennifer Charles, and Kid Koala.[42] The next year, Patton performed vocals for Dillinger Escape Plan's 2002 EP, Irony Is a Dead Scene.[43]

In 2004, Patton worked with Björk and the beat boxer Rahzel on the album Medúlla.[44] That same year, Patton released the album Romances with Kaada and contributed vocals to the album White People by Handsome Boy Modeling School (Dan the Automator and Prince Paul).[45][46] In 2005, Patton collaborated with hip-hop DJ trio and turntablists The X-Ecutioners to release the album General Patton vs. The X-Ecutioners.[47]

In February 2006, Mike Patton performed an operatic piece composed by Eyvind Kang, Cantus Circaeus, at Teatro comunale di Modena in Modena, Italy. Patton sang alongside vocalist Jessika Kinney, and was accompanied by the Modern Brass Ensemble, Bologna Chamber Choir, and Alberto Capelli and Walter Zanetti on electric and acoustic guitars. Patton remarked that it was extremely challenging to project the voice without a microphone.[48]

Patton's Peeping Tom album was released on May 30, 2006 on his own Ipecac label. The set was pieced together by swapping song files through the mail with collaborators like Dan the Automator, Rahzel, Norah Jones, Kool Keith, Massive Attack, Odd Nosdam, Amon Tobin, Jel, Doseone, Bebel Gilberto, Kid Koala, and Dub Trio.[49]

In May 2007, he performed with an orchestra a few concerts in Italy, by the name of Mondo Cane, singing Italian oldies from the 50s and the 60s.

In 2008, he performed vocals on the track "Lost Weekend" by The Qemists. In December 2008, along with Melvins, Patton co-curated an edition of the All Tomorrow's Parties Nightmare Before Christmas festival.[50][51] Patton chose half of the lineup and performed the album The Director's Cut in its entirety with Fantômas. Patton also appeared as Rikki Kixx in the Adult Swim show Metalocalypse in a special 2 part episode on August 24.[52]

In June 2009 Mike Patton & Fred Firth performed in Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, England as part of that year's Meltdown Festival.[53]

On May 4, 2010 Mondo Cane, where Patton worked live with a 30-piece orchestra, was released by Ipecac Recordings. The album was co-produced and arranged by Daniele Luppi.[54] Recorded at a series of European performances including an outdoor concert in a Northern Italian piazza, the CD features traditional Italian pop songs as well as a rendition of Ennio Morricone's 'Deep Down'.[55]

Patton is a member of the supergroup Nevermen, alongside Tunde Adebimpe of TV on the Radio and rapper Doseone (with whom Patton had previously collaborated on the Peeping Tom side-project).[56] In 2016, the group released an eponymous debut album on Patton's Ipecac label.[57]

In August 2017, Patton released a new album with the band Dead Cross, a supergroup that includes Slayer and Fantômas drummer Dave Lombardo and the members of Retox Michael Crain and Justin Pearson.[58]

On December 27, 2017, Patton performed his collaborative EP, Irony Is a Dead Scene, as well as a cover of Faith No More's "Malpractice," with the Dillinger Escape Plan live at the band's first of three final shows at Terminal 5 in New York City.[59]

In May 2018, Patton performed two concerts in Modena, Italy, with the American pianist Uri Caine. The setlists of the concerts varied and included songs from Erik Satie, Elton John, Slayer and Violeta Parra. They also performed a new song called "Chansons D'amour" from an album Patton would release with French musician Jean-Claude Vannier (September 2019's Corpse Flower). The shows were recorded, but it is not certain if the material will get a release.

Other ventures

Film work

In 2005, Patton signed on to compose the soundtrack for the independent movie Pinion, marking his debut scoring an American feature-length film. However, this had been held up in production and may be on the shelf permanently.[60] His other film work includes portraying two major characters in the Steve Balderson film Firecracker. He has also expressed a desire to compose for film director David Lynch.[61]

Patton provided the voices of the monsters in the 2007 film I Am Legend starring Will Smith.

He also worked on the Derrick Scocchera short film "A Perfect Place" for the score/soundtrack, which is longer than the film itself.[62]

In 2009, Patton created the soundtrack to the movie Crank: High Voltage.

In the 2010 film Bunraku Patton voiced The Narrator.

Patton composed the soundtrack to the 2012 film The Place Beyond the Pines.

In 2016, Patton provided the voice to lead character Eddy Table in a short animated film, The Absence of Eddy Table.

In 2017, he scored the Stephen King movie 1922 for Netflix.[63]

Video game work

Patton is known to be an avid video game player.[64] In 2007, he provided the voice of the eponymous force in the video game The Darkness,[65] working alongside Kirk Acevedo, Lauren Ambrose and Dwight Schultz. Patton reprised the role in The Darkness II in 2012.

He also had a role in Valve's 2007 release Portal as the voice of the Anger Sphere in the final confrontation with the insane supercomputer, GLaDOS. He has another role in the Valve title Left 4 Dead, voicing the majority of the infected zombies.[3] He also voiced Nathan "Rad" Spencer, the main character in Capcom's 2009 video game Bionic Commando, a sequel to their classic NES title.

Artistry

Voice, techniques and style

Mike Patton's vocals touch on crooning, falsetto, screaming, opera, death growls, rapping, beatboxing, and scatting, among other techniques.[37] While already a proficient singer, Patton is fond of manipulating his voice with effect pedals and diverse tools. This has been a prominent feature in his project Fantômas.[66] In a rundown on several songs sung by Patton, vocal coach Beth Roars distinguished his mastery of several styles from popular singers who usually focus on one approach, approximating Patton more to musical theater singers.[67] Critic Greg Prato writes, "Patton could very well be one of the most versatile and talented singers in rock music".[68] He also has basic knowledge on multiple instruments.[11]

Mike Patton achieved the first place in a May 2014 VVN Music's (Vintage Vinyl News) analysis ranking various rock and pop singers in order of their respective octave ranges.[69] The article served as a retraction to a previous article, which originally awarded the number one position to Axl Rose.[70] The article praised Patton's impressive 6 octaves, 1/2 note range (Eb1 to E7), versus Axl's admirable 5 octaves, 2-1/2 notes.[10] When asked about his range in a 2019 interview, he referred to the article: "I think that range thing is all bullshit. I don't think that I have the biggest range. And even if I do, who cares! ... This is not like the Olympics of vocals. [laughs] I could make a record without singing a note, and I'll be happy with it."[61]

Former bandmate William Winant singled out Patton's immediacy to concretize the musical ideas that he hears in his head,[12] while Faith No More bassist Billy Gould, after observing his reaction to the backbone of the songs from The Real Thing, concluded: "He was trying to figure us out at first, ... But he has this key to understanding music on a real gut level, and his ideas honestly made these songs even better."[71] Author Blake Butler called Patton "a complete and utter musical visionary and a mind-blowing and standard-warping genius."[72]

Patton is enthusiastic about collaborating with other musicians, stating that "It is really what makes life interesting",[73] but since the 2000s he has only participated in projects he feels close to.[74]

Phil Freeman of The Wire groups Patton with Tom Waits, Frank Zappa and Brian Wilson in what he calls 'California Pop Art' - artists from that area who adapted unconventional sources into their music and created pieces to then hire musicians capable of realizing them.[11] Several writers have likened Patton to Zappa (as well as their bands Mr. Bungle to Mothers of Invention) because of the quantity of their work, style-transcending influences and recurrent use of humor.[75][76][77] Patton is averse to this comparison,[22] but he admitted that one of the few records he enjoyed from his parents' collection was from Zappa.[76] Freeman believes that besides superficial elements, their music does not hold many similarities.[11]

Writing

—Mike Patton on his music, 2013[78]

Patton bases his vocal writing on what "the music dictates", whether that is using his voice in a traditional way or as "another [instrument]."[79] On many occasions, while working with bands or similar ensembles, he focuses on "blending [his voice] into the band" rather than being at the forefront of the pieces, like many rock music does. Patton feels that the best recordings have the vocals "a little buried in the mix" as they interact with the other instruments.[80] His composition process usually starts at the moment of listening to a new instrumental, where he tries to find its lead melody, either vocal or otherwise, imagining notes and sounds on top of it.[81][82] After that his writing naturally progresses, e.g. by employing a "third or fourth [harmony]" or "whatever [else] needs to be done".[82] Patton is inclined to produce dense overdubs that comprise numerous vocals or instrumentations in single passages.[83] When asked about the unorthodox use of his voice - drawing on diverse techniques and effects, or eschewing lyrics, Patton remarked: "The voice is an instrument. No rules, just part of the music."[84]

Patton creates lyrics after hearing the instrumentals[78] and, in the same way as the music, he approaches them depending on "what the music needs".[61] His songwriting takes a phonetic perspective instead of a literal one, making sounds paramount[71][81] – "the music tells the story", he says.[85] As soon as he creates the melodies, he generally seeks words that sound the most similar to what he heard in his head.[81] On the other hand, when working thematically, Patton says that each song is usually a character sketch acted out by him, "trying to appropriate their [respective] psycholog[ies]", and does not make them autobiographical.[81] Before writing, Patton tends to read books about the specific topic he wants to address and then fits it into "stolen ideas from other musicians."[86] He once expressed discomfort with penning lyrics,[78] and in some projects such as Fantômas he has avoided them completely in favor of preverbal sounds, believing that in these cases language would be "distracting information".[79] Patton's free-form approach, both vocally and lyrically, mirrors those of singers Demetrio Stratos[87] and The Boredoms' Yamantaka Eye.[11]

His early songs in Mr. Bungle dealt with "real nasty, offensive stuff".[88] By the time of 1989's The Real Thing, Patton was studying English literature in college and that led him to write the lyrics as if they were a "school project".[89]

On his method of composition for other musicians's pieces and filmmakers, Patton said that the most important quality is to remain flexible and open to any style, as well as to always follow the vision of the author.[90][61] His film score approach varies depending on what the directors seek; for example, the backbone of 1992 was written entirely on piano because the director wanted a restrained sound, whereas Crank was made on guitar since the mood of the film was aggressive.[61]

Music development

Patton claims that his parents became aware that he imitated bird vocalizations as a child and that prompted them to give him a flexi disc of vocal exercises, "like guys that could make odd sounds", which became one of his favorite records but without understanding its purpose at the time.[78] He realized the potential of his voice at the age of eight or nine by doing "things to get attention" at school.[84]

Mike Patton is "pretty much [a] self-taught" musician.[23] He developed the bulk of his style by mimicking[91][76] and drawing from all the singers whose music he admired.[71] Since he began to improvise with John Zorn in 1991,[92] along with his discoveries of Demetrio Stratos and Diamanda Galas, Patton started broad explorations into extended vocal techniques and the limits of his voice.[87][93] Many of these exercises were documented on his 1996 album Adult Themes For Voice.[94] His production methods also grew from him figuring out how to accomplish the sounds he tried to convey every time he was in his studio.[11] The Quietus remarked that "Though he feels no great regrets at his lack of formal training, and no jealousies towards those that have, he does occasionally wish he had the patience for such a course of study."[14]

He attributes much of his development to being part of projects with learned musicians.[78] At Humboldt State University, while he studied English literature, his Mr. Bungle bandmates Trevor Dunn, Trey Spruance, Danny Heifetz and Clinton McKinnon were all majoring in music.[95][96] Spruance highlights the great music resources in Humboldt's library, where he spent a lot of time studying,[15] and the band rehearsed at the same place as the college big band, in which the four of them played.[96] Composer and saxophonist John Zorn, who met Patton in 1990, is credited with teaching him "many things", such as vocal improvisation when performing with an ensemble.[11] In 2006, Patton said: "I've been incredibly fortunate to have a friend like that — who is also a peer and a mentor".[79] Some of his recording sessions with Zorn as conductor were so arduous that the singer passed out.[92]

Influences

Regarding his influences, Patton stated: "You should be able to draw inspiration from any and everything. There should be no limits, it's fundamental. A lot of people listen to music that I make and [do not understand why my songs are so eclectic. But] that's the way I listen to music! ... That's the way I see the world and that's how it comes out of me. ... The deeper that well [of inspiration] is and the more places you can find it, the better."[97] Detailing his composition process, Patton once paraphrased the T. S. Eliot quote, "Good artists copy; great artists steal."[86]

His first bands played heavy metal and by the start of Mr. Bungle the frontman was immersed in death metal and hardcore punk.[98] The band's second and third demos shifted its sound to ska and funk, and the last one of 1989 incorporated a wide variety of genres.[24] Patton considers his work at a record store as crucial for his and Mr. Bungle's evolution: upon his arrival, he "devour[ed]" extreme metal and punk music.[98][22] After a few years working there, the singer was allowed to commission albums to have them on sale, subsequently ordering "the craziest shit" he was aware of from diverse styles, with the secret intention of taking those records into his house to make copies of them that he and his bandmates would listen to. This rapidly led their music tastes to grow.[23]

Vocal influences

.jpg)

When asked about his influences and favorite singers in 1992, Patton said "A lot of people, I don't even know [where to start]", but among them mentioned Diamanda Galas, Frank Sinatra, Blixa Bargeld from Einstürzende Neubauten, H.R. from the Bad Brains, Chet Baker, Elton John and Obituary's John Tardy.[99][71] Several reviewers have noted similarities between his most adventurous works and the music of Galas,[100][101][102] and the solo performances and screams of Bargeld.[103][104] The frontman expresses much admiration for Sinatra's musicality, owning rare live records and outtakes from him, and considers unfortunate that the crooner's private life overshadowed his artistry.[23] Some authors observed that Bad Brains' H.R. presaged the dynamic delivery of Patton.[105][106]

One of Patton's biggest influences was Greek-Italian singer and researcher Demetrio Stratos, leader of Area, who studied the limits of the human range and recorded several vocals-only albums that Patton examined.[107][108] Stratos died unexpectedly amid his research, aged 34, and years later writer Anthony Heilbut referred to Patton as his "most famous heir".[87] The surreal vocals of Yamantaka Eye from The Boredoms and Hanatarash inspired the lyric-less compositions by the singer as well, and the former had also played with Naked City before Patton.[11]

His late 1980s nasal-funky rapping drew comparisons to that of Anthony Kiedis,[109][110][111] and Patton recognized funk rock bands such as Kiedis's Red Hot Chili Peppers and Fishbone as inspirations following Mr. Bungle's death metal beginnings.[21] He went on to be influenced by R&B singer Sade on his arrival to Faith No More,[112] reflected in later songs such as "Evidence".[113]

In 2019, he cited the spoken word-esque lyrical style of Leonard Cohen as inspirational, as well as the voice and note placement of Serge Gainsbourg,[23] in addition to the writing of Bob Dylan. Patton used to disregard these type of musicians when he was younger until he eventually "hear[d] new things" in them.[114]

Other influences

Early musical influences include Nomeansno and The Residents.[71] The Quietus pointed out "Patton's love of the Cardiacs, and musical digression" in general as well.[115][116] Patton held in high regard the Super Roots EP series by Boredoms, along with the albums Ozma by Melvins and Drop Dead by Siege.[117] He was also a big admirer of industrial metal band Godflesh[118] and invited its guitarist Justin Broadrick to join Faith No More after the departure of Jim Martin in 1993.[119] The Young Gods would go on to inform him and Faith No More's later use of samples.[120][121]

As of 1992, his favorite genre had become easy listening[99] and years later Patton named composer and arranger Les Baxter as the main influence on one of his film scores.[122] In 2005 the frontman proclaimed: "The orchestration in that music is so dense and so complex and so amazing, if you can get beyond the kitsch. And I can do that in 30 seconds flat. ... I hear new stuff in there every time I listen."[11] The writing by Patton is very influenced by orchestral pop composer Burt Bacharach[73] and in 2001 he publicly expressed his desire to work with him.[98] Additionally, the singer was "besotted" with the music of Jean-Claude Vannier after discovering his arrangements for Serge Gainsbourg, and the two went on to collaborate in 2019.[115]

Patton cited disco band Village People as an inspiration on his use of irony and stage costumes, believing that "a lot of people [did not] understand [the band's deliberate sarcasm]".[123] Mr. Bungle covered "Macho Man" as early as 1985 (its first active year).[124] Another ideological influence was shock rock singer GG Allin,[73] who Patton considered "the musician who never sold out" and admired that "he lived and died for what he believed in."[125]

Other musical influences are Olivier Messiaen, especially his transcriptions of birdsongs, and cartoon music composer Carl Stalling, who was a shared point of reference with John Zorn, whose PhD thesis was on him.[14] The singer expressed fondness for Mauricio Kagel's "negation of opera and the whole tradition of music theater."[14]

Public image

—Mike Patton, 2002[12]

Labelled as an "icon of the alt-metal world",[126] and a "reluctant pin-up boy",[71] Patton reacted strangely to his fame. According to a 2002 article from East Bay Express: "[Mike Patton]'s undeniably striking, with piercing Italian good looks and that inexplicable aura shared by first crushes, high-profile criminals, and celebrities ... And he's definitely, well, a little weird." The newspaper singled out his "straight-up devilish grin" and opined that Patton "seems to always be wrestling with some sort of suppressed Guido" through his different fashion styles through the years.[12]

Mr. Bungle, the band of Patton before his sudden rise to fame, already acted bizarrely in the late 1980s: they self-identified as "Star Wars action figure porno freaks", threw out underwears and bras into the audiences, among other antics.[127][128] In interviews with Faith No More from the early to mid-1990s, he went on to claim to be obsessed with masturbation,[129] to have defecated in an orange juice carton of Axl Rose[130] and in a hotel hair dryer,[131] to have munched on a tampon left on stage by a member of L7, to have lived with an aggressive lizard which inspired his lyrics, and many other things.[89] While Faith No More toured at that time, Patton began to carry a voodoo doll named Toodles, sadomasochistic gear, picture books of embalmed corpses and a pickled fetus in a jar.[89][131] During conversations with reporters, he only showed interest in discussing his "various obsessions" and did not like referring to his music.[131][89] On a January 1993 tour in France where a journalist accompanied them, Patton urinated into his shoe on stage before drinking it, and a few days later he percolated cups of coffee live for the audience.[131]

The North Coast Journal retrospectively pointed out the "profound lack of fact checking" by some journalists on Patton's statements,[132] and Culture Creature stated that it was hard to determine when he was teasing interviewers.[15] In a 2002 interview, answering the question of which aspects of his claims and public behavior were authentic, the frontman said: "The more misconceptions, the better".[12] Around ten years after the release of "Epic", the singer was approached to participate in an episode of the documentary series Where Are They Now? on VH1, to which Patton would only agree to do if they had depicted him as a real homeless person living in a cardboard box.[12] East Bay Express commented:

Patton is a genuine rarity: someone who started at the top [with The Real Thing in 1989] and willingly worked his way down [through his artistic and public endeavors following it.] ... To the mainstream, Patton's forays into noise and New Music are virtually unlistenable. To his colleagues and fervently loyal fans, however, Patton is a brilliant and versatile musician ...[12]

He has also expressed cynicism about the infamous lifestyles of rock stars. He told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1995, "It's hard to see as much as you'd like with our schedule on the road, but it's harder to do coke and fuck whores every night. Now that's a full time job."[133] In the 2000 essay How We Eat Our Young, he mocked the romanticization of popular musicians by comparing their work, including his, to peeping toms and thieves.[74] Patton was also fond of "play[ing] with" people whose "egos [got] tied in with" them, for example he constantly made fun of Anthony Kiedis in interviews after the latter accused him of stealing his style,[134] and afterward did the same with alternative rock band INXS who became upset when Patton turned down an offer to join them.[12] Consequence of Sound called Patton "the epitome of the anti-rock star."[135]

In the mid-2000s, Patton stopped to continually act irreverently offstage[11] and to claim strange things to interviewers;[74] by the last years of the next decade he had entirely ceased to do so. In 2019, he explained: "I'm already giving a thousand percent to the music ... and I realize what's important and what's not. ... There's an art to [talking to the press] ... And [on the other hand] fucking with [it] and being a dick it's not really worth it. ... and I learned that from an early age, ... there was a while when I was a total asshole and I didn't say anything and all I would do was give you a sarcastic answer, and spread out crazy lies and rumors just because it was funny [laughs] ... [but] I grew up ... And I think, I hope I've gotten a little better at that". The frontman concluded: "It's much easier to just be, what did I say to you before: the easiest thing in the world is just to be yourself."[23]

Fanbase

Although Faith No More had a major influence on several mainstream American acts, they found more commercial success in other territories after The Real Thing, such as Australia, Europe and South America.[136][137] Patton's charisma and artistry led the band to garner a "cult-like devotion" by numerous fans, as well as to treat him like, what some authors have described, a "deity".[138][139][14] Throughout the world, multiple online communities dedicated to Faith No More and Patton's projects have emerged since 1995, and many remain active.[140]

In 2002, he was reported as having a "mixed relationship" with his fanbase and the press, and, even though a non-reclusive person, he had been "freak[ed] out" by some aspects of his fame – "[Patton is] a private person who'd much rather shuffle through Burt Bacharach and Joe Meek CDs than talk about himself".[12] Notoriously, in 1993 an Australian female fan handcuffed herself to Patton when he was backstage, remaining so for two hours until personnel from Faith No More could free him.[141] Several fans had also tried to live outside of his house as of 1995.[142] Despite this, he kept conceding to talk or give interviews to his followers on several occasions while touring.[12] In later interviews, Patton thought to have "gotten better" at dealing with admirers and reporters.[143][23]

Personal life

_(4416923380).jpg)

Patton married Cristina Zuccatosta, an Italian artist, in 1994.[144] The couple divided their time between San Francisco and Bologna, Italy, until their separation in 2001,[144] but they later went back together.[74] Until 2001, Patton owned a home in Bologna and became a fluent speaker of Italian.[145] These events tied him closely to Italian culture and its popular music of the mid-20th century.[145][146] In addition, he was conversational in Spanish until the 1990s[147] and still understands it.[148] He also spoke Portuguese slang.[149]

The singer's numerous projects and constant touring have led him to be widely identified as a "workaholic".[150][143][144][151] Patton, who is addicted to coffee,[152] has kept around three projects going on simultaneously throughout the years.[74] He says that his workflow is "as normal as brushing [his] teeth"[74] and does not "feel comfortable unless [he has] got a few unfinished things".[12] In 2002, Patton admitted that his hectic schedule had hindered some of his personal relationships, but nonetheless he emphasized that music is his priority.[12] He has no children.[61] Patton enjoys his privacy and maintains few deep relationships in his life.[74][12]

Patton's right hand is permanently numb from an on-stage incident during his third concert with Faith No More, where he accidentally cut himself on a broken bottle and severed tendons and nerves in his hand. He learned to use his hand again, but has no feeling in it (despite his doctor telling him the opposite situation would happen).[153]

The frontman owns a large record collection and, as of 2005, he regularly traveled to Japan with John Zorn to buy albums.[11] He considers essential for him to discover new music, telling: "I like going into some place like Amoeba and saying 'O.K. what's gonna change my life today?'"[76]

Legacy

A list published by Consequence of Sound based on vocal range acknowledged Mike Patton as "the greatest singer of all time" in popular music.[10] Patton's role in Faith No More has often been credited as an influence to nu metal, a form of alternative metal spearheaded by bands such as Korn and Limp Bizkit in the late-90s.[155][156] He has been less than enthusiastic about being linked to such bands, stating in a 2002 interview that "Nu-metal makes my stomach turn".[157]

A reviewer at The Quietus opined that, notwithstanding Faith No More's far-reaching legacy, the most valuable contribution of Patton has been to use his platform "to become one of the most potent driving forces in avant-garde and alternative music", through his diverse projects and collaborations, and the experimental artists he has signed to Ipecac Recordings.[4]

Prominent vocalists such as Chino Moreno (Deftones),[158] Brandon Boyd (Incubus),[159][160] Jacoby Shaddix (Papa Roach),[161] Greg Puciato (The Dillinger Escape Plan),[162] Daryl Palumbo (Glassjaw),[163] Howard Jones (Killswitch Engage),[164][165] Tommy Rogers (Between the Buried and Me),[166] Daniel Gildenlöw (Pain of Salvation),[167] Doug Robb (Hoobastank),[168] Dimitri Minakakis (The Dillinger Escape Plan),[169] Mike Vennart (Oceansize),[170] Spencer Sotelo (Periphery)[171] and Kin Etik (Twelve Foot Ninja)[172] have cited Patton as their primary influence.

Devin Townsend proclaimed in 2011: "Angel Dust into Mr. Bungle changed every singer in heavy music. Patton is a living treasure."[173] Artistically, he has been named the biggest influence for Corey Taylor (Slipknot),[174] and a major one on Josh Homme (Queens of the Stone Age)[175] and The Avett Brothers.[176]

Selected filmography

- 1990 – Live at the Brixton Academy, London: You Fat Bastards by Faith No More (VHS)

- 1993 – Video Macumba – Short film compiled by Mike Patton containing abstract and extreme footage

- 1993 – Video Croissant by Faith No More (VHS) Released in 1993 it features some of the band's music videos up to that date.

- 1998 – Who Cares a Lot: Greatest Videos by Faith No More (VHS)

- 2002 – A Bookshelf on Top of the Sky: 12 Stories About John Zorn

- 2005 – Firecracker – Frank/David

- 2007 – Kaada/Patton Live – Live performance DVD

- 2007 – I Am Legend – Creature Vocals (voice) (credited as Michael A. Patton)[177]

- 2008 – A Perfect Place – Short film soundtrack by Patton (Released with film as CD/DVD special edition)

- 2008 – Live from London 2006 – Live DVD release of a performance by the Fantômas/Melvins Big Band in London on May 1, 2006

- 2008 – Metalocalypse – Patton voices the character of reformed rocker Rikki Kixx on episodes "Snakes n Barrels II" part one and part two. This special 2 part, half-hour presentation aired on Adult Swim August 24, 2008.

- 2009 – Crank: High Voltage – Film Score

- 2010 – The Solitude of Prime Numbers – Film Score

- 2010 – Bunraku – Narrator

- 2012 – The Place Beyond the Pines – Film Score

- 2016 – The Absence of Eddy Table – Voice of Eddy Table

- 2017 – 1922 – Film Score

Video game voice work

- 2007 – The Darkness – Voice of The Darkness (Starbreeze Studios)

- 2007 – Portal – Voice of the Anger Core (Valve)

- 2008 – Left 4 Dead – Infected voices, Smoker, Hunter (Valve)

- 2009 – Bionic Commando – Voice of Nathan Spencer – the Bionic Commando (Capcom)

- 2009 – Left 4 Dead 2 – Infected voices, Smoker, Hunter (Valve)

- 2012 – The Darkness II – Voice of The Darkness (Digital Extremes)

- 2016 – Edge of Twilight – Return to Glory – Vocals for Lithern and Creatures (FUZZYEYES)

References

- Shore, Robert (February 1, 2013). "Tomahawk, Soilwork, Wounds and Saxon: The best new heavy metal albums". Metro. Archived from the original on March 8, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- "Mike Patton to Score Horror Film "The Vatican Tapes"". Mxdwn.com. January 9, 2014. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Seff, Micah (June 7, 2007). "Mike Patton is The Darkness". IGN. Archived from the original on May 12, 2014.

- Thomson, Jamie (July 22, 2013). "Epic Fail: How Mike Patton Murdered Faith No More". The Quietus. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "Fantômas – Delìrium Còrdia". Uncut. December 1, 2003. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- Rule, Dan (December 14, 2007). "Stripping rock'n'roll". The Age. Archived from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- Fairbrother, Zach (May 24, 2019). "May 19' Compass: Zach's Facts // Funk Metal Feud". Boston Hassle. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

It was the late 80’s and funk metal had reached its apex in popular music. There were two undisputed titan’s in the field, The Red Hot Chili Peppers led by Anthony Kiedis and Faith No More fronted by Mike Patton

- Haire, Chris (August 12, 2009). "Psychostick returns funk metal to its silly roots". Charleston City Paper. Archived from the original on August 13, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- Zorn, John, ed. (2000). Arcana: Musicians on Music. New York: Granary Books/Hips Road. ISBN 1-887123-27-X.

- Coplan, Chris (May 25, 2014). "Turns out Mike Patton, and not Axl Rose, is the greatest singer of all time". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on May 27, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Freeman, Phil (April 2005). "Mike Patton | Fantômas hysteria". The Wire. No. 254.

- St. Clair, Katy (July 10, 2002). "Loco Hero". East Bay Express. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- McPadden, Mike (November 26, 2014). "20 Native American Rockers That We're Thankful For This Thanksgiving". VH1. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Barry, Robert (May 5, 2010). "A Deathly Plague: Mike Patton Talks About Mondo Cane And Avant Metal". The Quietus. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Redding, Dan (August 30, 2016). "Interview with Trey Spruance of Mr. Bungle, Faith No More, Secret Chiefs 3". Culturecreature.com. Event occurs at 3:06-4:25 and 4:51-6:17 (Eureka's isolated and religious culture), 6:45-9:04 (freighthopping), 11:15-12:45 (music classes in school and university), 27:21-27:37 (Faith No More interviews). Archived from the original on September 2, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Gemini, la banda de Mike Patton antes de Mr Bungle". Radio Futuro (in Spanish). August 20, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Bennett, J. (March 24, 2020). "Mr. Bungle Studio Report, Part 2: Thrash, Lyrics, "Death-Metal Virgins"". Revolver. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Burns, Ryan (August 13, 2019). "Eureka-Born Avant-Rock Legends Mr. Bungle Announce Reunion Shows with Members of Anthrax, Slayer". Lostcoastoutpost.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "Mike Patton And The Mr Bungle Tape". October 4, 2015. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- Dick, Jonathan (May 28, 2015). "Faith No More's Mike Patton: 'You Create Your Own Freedom'". NPR. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Hart, Ron (June 20, 2019). "Faith No More's 'The Real Thing' at 30: How They Switched Singers & Delivered a Classic". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 21, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Páez, Daniel (February 17, 2007). "La promiscuidad hecha música, entrevista exclusiva a Mike Patton". Equinoxio.org (in Spanish). Archived from the original on February 21, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Phillips, Lior (September 18, 2019). "Mike Patton on Joining Faith No More, Finding Inspiration from Tom Waits, and Being Yourself". This Must Be the Gig (Podcast). No. 68. Consequence of Sound. Event occurs at 12:02: 16:20-16:42 (meeting Faith No More), 19:06-21:09 (record store), 26:18-26:40 and 27:44-28:19 (self-taught), 30:37-31:18 (growing up in a small town), 33:50-35:05 (Cohen and Gainsbourg), 35:19-36:37 (Sinatra), 37:53-39:17 (relationship with the press). Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Rowland, Jamie (October 22, 2005). "Mr. Bungle - Profile Part 1". Pennyblackmusic.co.uk. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "Famous Humboldt: From the redwoods to the limelight". Times-Standard. June 28, 2011. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- "Video: FAITH NO MORE Rejoined By Former Singer CHUCK MOSLEY On Stage In Detroit". May 9, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- "Faith No More Reuniting With Original Singer Chuck Mosley for Two Shows". Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- Cee, Gary (November 30, 1990). "Faith No More: Inside the insatiable Mike Patton". Circus Magazine. No. #369. pp. 62–64. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- Stratton, Jeff (October 20, 1999). "Mike Patton of Mr. Bungle". The A.V. Club. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- Mike Patton, June 30, 2001, Wâldrock Festival

- "Faith No More To Reform!". Uncut. February 25, 2009. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- "In stores this week: Faith No More best-of, new CDs from Elvis Costello, Simple Minds". slicing up eyeballs // 80s alternative music, college rock, indie. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- Samborska, Agatha (ed.). "Faith No More Frequently Answered Questions". Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- Greg Prato. "Mr. Bungle – Music Biography, Streaming Radio and Discography – AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Greg Prato. "Disco Volante – Mr. Bungle – Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards – AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- "Mr. Bungle Go Kaput : Rolling Stone". May 3, 2008. Archived from the original on May 3, 2008.

- Vang 2013, text.

- DeRogatis, Jim (November 2, 2001). "Super Models: New Bands Show That Supergroups Can Get It Right". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2001. (subscription required)

- "Tomahawk – Tomahawk – Songs, Reviews, Credits – AllMusic". Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- Kreps, Daniel (January 17, 2013). "Hear Tomahawk's Hypnotic 'Oddfellows' Title Track". Spin. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- Moss, Corey. "Deftones' Singer's Team Sleep Project Awakening On West Coast". Mtv.com.

- Mike Patton at AllMusic

- "Irony Is a Dead Scene – The Dillinger Escape Plan". Allmusic.

- "Interview: Bjork – Uncut". Uncut. November 5, 2004. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- "Romances – Kaada/Patton – Songs, Reviews, Credits – AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- Jeffries, David. "Handsome Boy Modeling School – White People". AllMusic.

- Mike Patton at AllMusic

- "404". Archived from the original on March 21, 2006. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- Andy Couch. "Ipecac Recordings". Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- "Nightmare Before Christmas curated by Melvins and Mike Patton – All Tomorrow's Parties". Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Allen, Jeremy (July 30, 2010). "Mike Patton interview". stoolpigeon.co.uk. Archived from the original on July 30, 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Mike Patton on IMDb

- "Meltdown 2009 – eFestivals.co.uk". www.efestivals.co.uk. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- "Mike Patton – Mondo Cane", Discogs.com, Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- "MIKE PATTON's MONDO CANE To Release Debut in May". Archived from the original on March 14, 2010.

- Payne, Chris (August 5, 2015). "TV on the Radio, Faith No More Members Form Nevermen Supergroup, Share 'Tough Towns' Song". Billboard.

- Ham, Robert (January 29, 2016). "Nevermen's self-titled album brings delicious, thick swirls of modern electronica". Alternative Press. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- "Dead Cross' Mike Patton, Dave Lombardo Talk Spastic New Album". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- "Mike Patton joining Dillinger Escape Plan at final show run to perform their collab EP". BrooklynVegan. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- "synthesisradio.net". Archived from the original on February 27, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Shand, Lauren; Shand, Trevor; D'Antonio, Leone (November 6, 2019). "[Podcasts] Mike Patton Schools The Boo Crew on Horror Flicks and Film Scores". Bloody Disgusting (Podcast). No. 82. Event occurs at 8:09 (childless), 13:58-15:27 (approach in film scores), 15:27-16:22 (workflow when working for filmmakers), 19:42-20:13 (dream collaboration with a director), 22:40-23:27 (production techniques and vocals), 23:41-24:22 (vocal range), 25:40-26:37 (lyrical approach). Archived from the original on November 7, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Mike Patton". PopMatters. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- "Faith No More's Mike Patton Scores Stephen King's 1922". Blabbermouth. October 20, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- Andy Couch. "Ipecac Recordings". Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- "The Darkness Preview – Shacknews – PC Games, PlayStation, Xbox 360 and Wii video game news, previews and downloads". Archived from the original on June 8, 2007. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- Pehling, Dave (March 19, 2018). "Local Avant-Rock Singer Teams With Saxophone Iconoclast". CBS Television Stations. San Francisco. Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "Watch a Vocal Coach Analyze Mike Patton's Many Vocal Styles". Ghostcultmag.com (video). May 21, 2019. Event occurs at 8:28-9:13. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Prato, Greg. "Mike Patton Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- "Digging Deeper: Axl Rose is NOT the Singer With the Widest Range ~ VVN Music". Vintage Vinyl News. Archived from the original on July 7, 2016. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Coplan, Chris (May 19, 2014). "Axl Rose is the greatest singer of all time — or, so says this char". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on May 20, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- Sherman, Lee (September 1992). "Faith No More | Get the Funk Out". Guitar Magazine. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Butler, Blake. "Tomahawk – Tomahawk – Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards – AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- "One on One with Mike Patton". Hobotrashcan.com. August 9, 2007. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "A Conversation with Mike Patton". Wortraub.com. June 1, 2006. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "Mike Patton | The Exclaim! Questionnaire". Exclaim!. April 1, 2005. Archived from the original on September 7, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "Mike Patton of Faith No More and Mr. Bungle Still Feels Lucky". Boston (published October 14, 2008). 1999. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Portnoy, Mike (June 25, 2016). "Rock Icons: Frank Zappa by Mike Portnoy". LouderSound.com. Archived from the original on December 29, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Simonini, Ross (January 1, 2013). "An Interview with Mike Patton". The Believer. No. 95. San Francisco. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Davies, Bren (May–June 2006). "Mike Patton: Faith No More, Mr. Bungle, Tomahawk, Fantomas". Tape Op. No. 53. New York City. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Vang 2013, 0:06-2:33.

- "Mike Patton speaks about leftover songs and lyrics to Rock Hard France". Newfaithnomore.com. May 12, 2015. Archived from the original on July 9, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Vang 2013, 7:00-7:40.

- Vang 2013, 7:39-8:19.

- "L'intervista dei Fantofan a Mike Patton". King for a day. Viareggio, Italy. June 2006. pp. 4–5. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Full Metal Jackie (September 11, 2017). "Mike Patton Hopes Dead Cross Will Release 'A Few More Records,' Faith No More on 'Extended Break' [Interview]". Loudwire. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Fuguet, Alberto (November 11, 2011). "Mike Patton: "La música fue una manera de mantenerme ocupado"". Chileanskies.com (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile (published November 12, 2011). Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Heilbut, Anthony (July 1, 2012). "The Male Soprano". The Believer. No. 91. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Mouth Off". Faces Magazine. July 1990. Archived from the original on July 20, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Sutcliffe, Phil (June 1, 2009). "From The Archives: Faith No More Interviewed By Phil Sutcliffe In 1995". The Quietus. San Francisco: Rock's Backpages . Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Vang 2013, 5:39-6:59.

- Hodgson, Peter (November 10, 2012). "INTERVIEW: Mike Patton". Iheartguitarblog.com. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Shteamer, Hank (June 22, 2020). "'He Made the World Bigger': Inside John Zorn's Jazz-Metal Multiverse". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 23, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "Mike Patton Interview | Peeping Tom | MTV Italy 2006 (2/2)" (video).

- Suarez, Gary (April 29, 2010). "HOW THE HELL DID GARY SUAREZ LAND AN INTERVIEW WITH MIKE PATTON?". MetalSucks. Archived from the original on May 2, 2010. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

... But to me, [Adult Themes for Voice] was a learning experience. I was literally exercising my voice for the whole world to hear. And here I was learning, on the job, how to use certain techniques that I thought I could get better at.

- Bottams, Timothy (November 25, 2019). "The Bär Sound of Mr. Bungle". Theswinstandard.net. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Shteamer, Hank (March 2011). "Heavy Metal Be-Bop #3: Interview with Trevor Dunn". Invisible Oranges (published May 13, 2011). Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "William Shatner | Peeping Tom". The Henry Rollins Show. Season 2. Episode 8. IFC. June 1, 2007.

- Young, Simon (October 13, 2001). "The Wanderer". Kerrang!. No. 876.

- Zahn, James (September 22, 1992). "Exclusive - FAITH NO MORE: THE LOST INTERVIEWS (1992, Cable Access)". Therockfather.com (video). Davenport, Iowa: ZTV (published July 7, 2010). Event occurs at 1:15-1:43 (influences) and 1:44-2:08 (easy listening) in the eleventh/last video on the playlist. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "Necroscape | Tetema". Metalnews.fr (in French). May 6, 2020. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Hartmann, Andreas (April 29, 2005). "Es ist nicht alles Gold, was kotzt". Die Tageszeitung (in German) (7652). p. 15. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Mullett, Jimmy (January 13, 2017). "Heavy Vanguard Episode 8: Diamanda Galás // The Divine Punishment". Heavyblogisheavy.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Heilbut, Anthony (June 19, 2012). "The Male Soprano". The Fan Who Knew Too Much. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 277. ISBN 0307958477. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

... [Analyzing Patton's shrieks:] they're embedded between strong-man growls and baby squeals–for him, too, the ultimate freedom is not female but infantile. So far he hasn't published manifestos like Stratos or Bargeld, though he clearly shares their ideology.

- Shryane, Jennifer (October 2009). "A Study of Einstürzende Neubauten" (PhD thesis). University of Liverpool (University of Chester): 229 and 268. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Avril, Pierre (October 6, 2016). "Camion Blanc: PUNK & METAL Des liaisons dangereuses" (in French). Camion Blanc. p. 182. ISBN 2357798696. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

Le chant de HR se fait plus mélodique, et nous permet de profiter de toute l'étendue de ses talents vocaux. ... [I Against I] nous envoie dans les cages à miel ce qu'on peut considérer comme l'ouvrage sur lequel la scène Fusion Metal/Funk/HipHop à venir va se baser. Écoutez le fabuleux «Reignition» pour vous faire une idée: HR y croone d'une façon qu'un certain Mike Patton (Faith No More, Mr Bungle) va largement imiter, ...

- Begrand, Adrien (September 9, 2003). "Bad Brains: Banned in D.C.: Bad Brains Greatest Riffs". PopMatters. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

[H.R.'s] astonishingly versatile voice shows jaw-dropping range, something that the likes of Mike Patton and Serj Tankian would emulate years later.

- Galati, Arianna (January 26, 2018). "Tanti auguri Mike Patton, voce da record". Esquire (in Italian). Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- Santoro, Gianni (May 29, 2015). "Faith No More, il ritorno degli outsider del rock". la Repubblica XL (in Italian). la Repubblica. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- Berman, Stuart (June 10, 2015). "Faith No More: The Real Thing". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on June 11, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Condran, Ed (October 4, 1992). "NOW A HEADLINER, FAITH NO MORE LETS 'DUST' SETTLE". The Morning Call. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Klaas, Michael (December 13, 2018). "Faith No More - The Real Thing". Metal.de. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Prato, Greg (Summer 2005). "Faith No More: The Real Story". Classic Rock. No. 83 (published April 22, 2014). Archived from the original on May 24, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Jai Young Kim (November 18, 1994). "Interview: FAITH NO MORE". Feastorfamine.com. San Francisco: Rockerilla. Archived from the original on July 17, 2001. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Ludwig, Jamie (September 5, 2019). "Mike Patton, Jean-Claude Vannier Collaboration Predicated on Versatility". DownBeat. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 13, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Allen, Jeremy (September 3, 2019). "Reanimator: Mike Patton And Jean-Claude Vannier On Corpse Flower". The Quietus. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Sacher, Andrew (July 22, 2020). "mems of Faith No More, Porcupine Tree, Blur, Voivod, Pinback & more pay tribute to Cardiacs' Tim Smith". BrooklynVegan. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "My Record Collection (Mike Patton)". Kerrang!. June 14, 1997. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Patton, Mike (1992). "The Making of Angel Dust" (Interview). MTV. Event occurs at 6:33-6:36 and 7:30-8:07 (Godflesh), 8:07-8:13 (Melvins). Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Walschots, Natalie Zina. "Faith No More – Return of the King". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Baillargeon, Patrick (August 21, 2019). "De retour au Québec : La longue route des Young Gods". Voir (in French). Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Reinhard, Samuel (January 26, 2015). "Interview: The Young Gods' Franz Treichler on 30 Years of Music". Red Bull Music Academy. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Macaulay, Scott (April 1, 2013). "The Tone of Destiny". Focusfeatures.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Dann, Pip (August 1990). Faith No More. Rage. Australia: ABC.

- "Bister Mungle (Mr Bungle) Eureka High School Talent Show 1985 (Full Show)" (video). Event occurs at 13:14. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "my Patton interview ( March 2005 via email )". Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Lymangrover, Jason. "Zu | Carboniferous". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- Sadie O. (Fall 1989). "MR. BUNGLE". Face It!. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "Mr. Bungle Radio Interview (For Locals Only) 1988". For Locals Only. Arcata, California: KFMI (published September 7, 2017). June 1, 1988. Event occurs at 0:43, 21:01. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- https://books.google.com/books?id=RDWxkmx1bj4C&pg=PA36

- Walschots, Natalie Zina (June 5, 2015). "Five Noteworthy Facts You May Not Know About Faith No More". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on June 6, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Morris, Gina (March 1, 1993). "Faecal Attraction". NME. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Cahill, Jennifer Fumiko (June 26, 2019). "From the Mouths of Bands: Spin's Faith No More Flashback". North Coast Journal. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Snyder, Michael (March 3, 1995). "KEEPING THE FAITH / Bay Area band revamps and goes back on the road". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Phair, Jon (May 1995). "Interview with Mike Patton". Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Young, Alex (February 21, 2010). "Icons of Rock: Mike Patton". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on February 26, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Penguin Pete (August 16, 2014). "Return of the Unique One-Hit Wonder Stories". Lyricinterpretations.com. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Paul, George A. (December 1, 2010). "Faith No More powerful at Palladium opener". Orange County Register. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Rosenberg, Axl; Krovatin, Christopher (October 24, 2017). "A Crash Course in Alternative Metal". Hellraisers: A Complete Visual History of Heavy Metal Mayhem. Race Point Publishing. p. 118, 119. ISBN 1631064304.

FNM fans are cult-like in their devotion, treating charismatic, versatile vocalist Mike Patton as a deity.

- "The Wonderful Weird of Mike Patton". Silentmotorist.media. April 25, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "MULTI-ENTREVISTA: Fans de Faith No More opinan de Sol Invictus y más!". Faithnomore4ever.com (in Spanish). July 19, 2015. Archived from the original on June 23, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Gullick, Steve (July 17, 1993). "Faith No More Set Phonix Alight". Melody Maker. Odense, Denmark. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Morris, Gina (March 1995). "Oh No, Not Again..." Select. Venice, Italy. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Drever, Andrew (December 5, 2003). "Patton pending". The Age. Archived from the original on December 23, 2003. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Mathieson, Craig (November 3, 2012). "The leap from Faith". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Florino, Rick (March 29, 2010). "Faith No More's Mike Patton on Mondo Cane — "I was living a completely different experience, and that was Italy"". Artistdirect. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- Mastrapa, Gus (July 17, 2008). "Mike Patton". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on November 3, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Rocca, Jane (June 4, 2010). "Vocalist turns Italian love affair into a serenade". The West Australian. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "Unpublished Mike Patton interview from March 2003". Bunglefever.com. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Raphael, Amy (August 1992). "Ten Minutes in the Mind of MIKE PATTON". The Face. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Davey, Melissa (November 21, 2016). "Faith No More's Mike Patton talks about new side project tetema: 'It's very, very tricky'". The Guardian. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Calia, Mike (June 16, 2019). "30 years after his Faith No More breakthrough, Mike Patton owns a record label that keeps turning profits". CNBC. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Lymangrover, Jason (March 18, 2008). "Mike Patton 101". AllMusic. Archived from the original on December 29, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Epstein, Daniel Robert (May 29, 2006). "Mike Patton Interview". SuicideGirls. Archived from the original on June 16, 2006. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- Downs, David (January 17, 2007). "Orinda's Noise Vomitorium". East Bay Express. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Mehling, Shane (August 13, 2015). "They Did It All for the Nookie: Decibel Explores the Rise and Fall of Nu-Metal". Decibel. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- Ratliff, Ben (August 13, 2002). "ROCK REVIEW; It's All About Artifice (and Croons and Growls)". The New York Times. New York City (published August 16, 2002). Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Patterson, Dayal (March 11, 2009). "Why The World Doesn't Need New Nu Metal". The Quietus. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- Dunn, Sam (2010). "DEFTONES' Chino Moreno on vocal influences and nu metal | Raw & Uncut". Bangertv.com (video). Toronto: Banger Films (published June 27, 2017). Event occurs at 1:08-1:17 and 2:39-3:52. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- Moss, Corey (December 6, 2001). "Hoobastank 'Crawling' Out Of Incubus' Shadow". Mtv.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

Dan Estrin (Hoobastank guitarist): We have a lot of people that bash us because they think we sound just like Incubus, a lot of people don't understand that we're all the same age, we grew up in the same neighborhood and we're influenced by the same bands. Both our singers were heavily influenced by Mike Patton from Faith No More or Mr. Bungle.

- Farber, Jim (March 7, 2002). "CORNERING THEIR SPOT". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Prato, Greg (April 12, 2015). "Jacoby Shaddix of Papa Roach : Songwriter Interviews". www.songfacts.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

Mike Patton is one of my favorite singers. Faith No More, one of my favorite bands of all time. Very inspiring to me. I fell in love with that band at a very young age, and I saw them a few times growing up. I was bummed out when they parted ways [in 1998], but they're doing shows again, which is awesome. But as far as influence, the way that I sing, I definitely was inspired by Mike Patton [...]

- Prindle, Mark (September 2003). "Greg Puciato – 2003". www.markprindle.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

Growing up, I was always a huge fan of his. If there's anybody that I tried to mimic when I was a kid, it was him [Mike Patton]. I probably wouldn't have even started singing if it wasn't for him. He and H.R. from Bad Brains were my two big influences when I first started it when I was really young. Not only is it an awesome honor and everything to have to come after him, but it's also not as difficult as you would think just because I was already so influenced by him to begin with.

- "DARYL of GLASSJAW". www.showandtellonline.com. June 2002. Archived from the original on January 10, 2003. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

Q: Was Mike Patton a big influence on you?

Daryl Palumbo: Growing up he was one of my heroes... absolutely. I want to say no because I hear he’s a bitter old man and that he laughs at bands that cite him as an influence. Everybody on M-fucking-TV and all heavy bands everywhere site Patton as an influence and he talks shit about them? I still think he is the greatest singer in heavy music history but I feel way above any other band that cites him as an influence. Fuck it if he has a problem with it. - "Up all night: Q&A with Devil You Know vocalist Howard Jones; band set to perform at El Paso's Tricky Falls". El Paso Times. Los Angeles, California. July 9, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

Q: Your voice is very unique in that you can go from very melodic to very heavy from one phrase to the next. Who are some of your influences and where did you learn to sing so melodically?

Howard Jones: I think, obviously, Mike Patton from Faith No More is a big one. [...] - Mahsmann, Steffi (March 29, 2004). "KILLSWITCH ENGAGE (HOWARD JONES)". Terrorverlag.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

[...] I’d say that the band that probably influenced me more than any was probably Faith no more. Just because I listened to it so much, when they were active. [...] I would say “The last to know” by Faith no more! I sing that song in the shower all the time. And I actually wrote the chorus to the song “Breathe life” on our album, I wrote that in the shower. (laughs)

- "Giles - Interview mit Thomas Giles Rogers, Jr". BurnYourEars (in German). June 27, 2005. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Menegakis, Michael. "Here is a Pain of Salvation interview with Daniel Gildenlow from March 1999". Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- McKinny, Brian (February 14, 2013). "HOOBASTANK'S DOUG ROBB: ROCK STAR AND DEVOTED DAD". musicinsidermagazine.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- Webb, Brian (November 1, 2000). "Interview: Dillinger Escape Plan". Theprp.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

Q: Who would you list as your influences?

Dimitri Minakakis: [...] Mike Patton is a big influence on me. When I was 12 or 13, that's when they came around. [...] - Jentsch, Thomas (December 11, 2003). "Oceansize im Interview @ HELLDRIVER MAGAZINE (Dezember 2003)". Helldriver-magazine.de (in German). Würzburg. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

I'm a big fan of almost everything Mike Patton does. My favourite is Mr. Bungle. He's probably the reason why I even thought about singing.

- Tristan (January 6, 2016). "An Interview With : Spencer Sotelo (Periphery)". themetalist.net. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- "EXCLUSIVE: INTERVIEW WITH NIK "KIN" ETIK OF TWELVE FOOT NINJA !!" (in English and Japanese). September 20, 2016. Archived from the original on December 19, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "Devin Townsend on Twitter". August 25, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Aroesti, Rachel (March 1, 2018). "Elvis Presley's power, Tina Turner's legs: musicians pick their biggest influences". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 2, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Kaufman, Spencer (September 13, 2018). "Preview: Joshua Homme calls Mike Patton a "big influence" in new episode of Alligator Hour on Apple Music's Beats 1". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on September 14, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Mervis, Scott (May 26, 2011). "The Avett Brothers (and dad) come north". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Andy Couch. "Ipecac Recordings – News". Ipecac.com. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

Sources cited

Vang, Jes (2013). "Mike Patton – Vocal Alchemist" (video and text). TC-Helicon. Archived from the original on July 22, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mike Patton |