Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-23

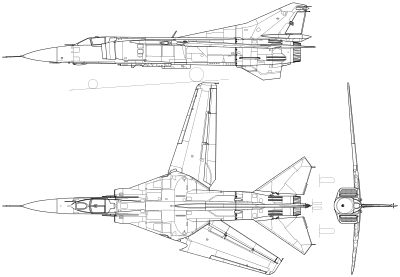

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-23 (Russian: Микоян и Гуревич МиГ-23; NATO reporting name: Flogger) is a variable-geometry fighter aircraft, designed by the Mikoyan-Gurevich design bureau in the Soviet Union. It is a third-generation jet fighter, the world's most-produced variable-geometry aircraft, along with similar Soviet fighters such as the Su-15 "Flagon". It was the first Soviet fighter to field a look-down/shoot-down radar and one of the first to be armed with beyond-visual-range missiles. Production started in 1969 and reached large numbers with over 5,000 aircraft built. Today the MiG-23 remains in limited service with some export customers.

| MiG-23 | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Soviet Air Force MiG-23MLD | |

| Role | Fighter aircraft (M series) Fighter-bomber (B series) |

| National origin | Soviet Union |

| Manufacturer | Mikoyan-Gurevich / Mikoyan |

| First flight | 10 June 1967 |

| Introduction | 1970 |

| Status | In limited service |

| Primary users | Soviet Air Force (historical) Syrian Air Force Indian Air force(historical) Bulgarian Air Force (historical) See Operators below |

| Produced | 1967–1985 |

| Number built | 5,047 |

| Unit cost |

$3.6–6.6 million (1980)[1] |

| Variants | Mikoyan MiG-27 |

The basic design was also used as the basis for the Mikoyan MiG-27, a dedicated ground-attack variant. Among many minor changes, the MiG-27 replaced the MiG-23's nose-mounted radar system with an optical panel holding a laser designator and a TV camera.

Development

The MiG-23's predecessor, the MiG-21, was fast and agile, but limited in its operational capabilities by its primitive radar, short range, and limited weapons load (restricted in some aircraft to a pair of short-range R-3/K-13 (AA-2 "Atoll") air-to-air missiles). Work began on a replacement for the MiG-21 in the early 1960s. The new aircraft was required to have better performance and range than the MiG-21, while carrying more capable avionics and weapons including beyond-visual-range (BVR) missiles. A major design consideration was take-off and landing performance. The VVS demanded the new aircraft have a much shorter take-off run. Low-level speed and handling was also to be improved over the MiG-21. Manoeuvrability was not an urgent requirement. This led Mikoyan to consider two options: lift jets, to provide an additional lift component, and variable-geometry wings, which had been developed by TsAGI for both "clean-sheet" aircraft designs and adaptations of existing designs.[2][3]

The first option, for an aircraft fitted with lift jets, resulted in the "23-01", also known as the MiG-23PD (Podyomnye Dvigatyeli – lift jet), was a tailed delta of similar layout to the smaller MiG-21 but with two lift jets in the fuselage. This first flew on 3 April 1967, but it soon became apparent that this configuration was unsatisfactory, as the lift jets became useless dead weight once airborne.[4][5] Work on the second strand of development was carried out in parallel by a team led by A.A Andreyev, with MiG directed to build a variable-geometry prototype, the "23-11" in 1965.[6]

The 23-11 featured variable-geometry wings which could be set to angles of 16, 45 and 72 degrees, and it was clearly more promising. The maiden flight of 23–11 took place on 10 June 1967, flown by the famous MiG test pilot Aleksandr Vasilyevich Fedotov (who set the absolute altitude record in 1977 in a Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-25).[7] Six more flight prototypes and two static-test prototypes were prepared for further flight and system testing. All featured the Tumansky R-27-300 turbojet engine with a thrust of 77 kN (17,300 lbf). The order to start series production of the MiG-23 was given in December 1967. The first production "MiG-23S" (NATO reporting name 'Flogger-A') took to the air on 21 May 1969, with Fedotov at the controls.[8]

The General Dynamics F-111 and McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II were the main Western influences on the MiG-23. The Soviets, however, wanted a much lighter, single-engined fighter to maximize agility. Both the F-111 and the MiG-23 were designed as fighters, but the heavy weight and inherent stability of the F-111 turned it into a long-range interdictor and kept it out of the fighter role. The MiG-23's designers kept the MiG-23 light and agile enough to dogfight with enemy fighters.

Design

Armament

The MiG-23's armament evolved as the type's avionics were upgraded and new variants were deployed. The earliest versions, which were equipped with the MiG-21's fire control system, were limited to firing variants of the R-3/K-13 (AA-2 "Atoll") missile. The R-60 (AA-8 "Aphid") replaced the R-3 during the 1970s, and from the MiG-23M onwards the BVR R-23/R-24 (AA-7 "Apex") was carried. The MiG-23MLD is capable of firing the R-73 (AA-11 "Archer"), but this missile was not exported until the MiG-29 was released for export. The helmet-mounted sight associated with the R-73 missile was fitted on the MiG-23MLDG and other experimental MiG-23MLD subvariants that never entered production as had been originally planned. The reason was that these MiG-23MLD subvariants had less priority than the then ongoing MiG-29 program, and the Mikoyan bureau therefore decided to concentrate all their efforts on the MiG-29 program and halted further work on the MiG-23. Nevertheless, a helmet-mounted sight is now offered as part of the MiG-23-98 upgrade. There were reports of the MiG-23MLD being capable of firing the R-27 (AA-10 "Alamo") beyond experimental tests; however, it seems only Angola's MiG-23-98s are capable of doing so. A MiG-23 was used to test and fire the R-27, R-73, and R-77 (AA-12 "Adder") air-to-air missiles during their early flight and firing trials. Ground-attack armament includes 57 mm rocket pods, general-purpose bombs up to 500 kg in size, gun pods, and Kh-23 (AS-7 "Kerry") radio-guided missiles. Up to four external fuel tanks could be carried.

Cockpit

The MiG-23's cockpit was considered an improvement over previous Soviet fighters as it took greater account of human factors in its layout. It was however a "very busy" cockpit, preoccupying the pilot with manipulating switches and monitoring gauges, compared to more modern aircraft with HOTAS controls. The instrument panel did feature a white stripe to serve as a visual aid for centering the control column during an out-of-control situation.[9][10] To prevent the pilot from exceeding a 17° angle of attack, the control column incorporated a "knuckle rapper" which would strike the pilot's knuckles as they approached the limit.[9]

Cockpit visibility was also somewhat poor in the MiG-23, although the view straight ahead was superior compared to the MiG-21.[10] In particular visibility was poor looking to the rear, partially due to the fighter's ejection seat which wrapped around the pilot's head, requiring the pilot to lean forward to look to the side or behind them. To assist with looking directly behind the pilot, the cockpit was fitted with a mirror or 'periscope' embedded in the middle rail of the canopy similar to on the MiG-17. With an infinity focus, the periscope provided a clear view of behind the plane, but did not have a wide field of view.[9][10]

The MiG-23's ejection seat, the KM-1, was built with extreme altitude and speed in mind: leg stirrups, shoulder harness, pelvic D-ring, and a 3-parachute system. Engaging the ejection seat could take a long time, as the pilot had to place their feet in the stirrups, let go of the control column, grab the two trigger handles, squeeze and lift them. The first parachute, the size of a large handkerchief, was deployed out of a telescoping rod which would pop out of the top back of the seat as it started to clear the windscreen windbreak area. It was supposed to help rotate the seat into the windblast and stabilize into a flight path that would take it above and behind the vertical stabilizer. As the first chute and rod separated from the seat, a larger drogue parachute deployed to slow down the seat, allowing the deployment of the main parachute. If engaged at low altitudes, the seat included a barometric element that allowed the drogue chute to separate more quickly. One problem with the KM-1 was that it was not a zero-zero ejection seat, and would only work at a minimum speed of 90 knots.[11]

Control Surfaces

The MiG-23 was among the first Soviet aircraft to feature variable-geometry wings. These were hydraulically controlled by means of a small lever set beneath the throttle in the cockpit. There were three main sweep angles that were set by the pilot for different levels of flying. The first, with the wings fully spread at 16°, was used when cruising at below Mach .7 or when taking off and landing. Putting the wings at mid-spread of 45° was used for basic fighter maneuvering, as well as cruising at high speeds or making low-altitude intercepts. Moving the wings to fully swept at 72° was reserved for making high-altitude intercepts or high-speed dashes at low altitudes.[12] Starting with the Type 1971 model the MiG-23's wings had their surface area increased by 20%, necessitating the positions be changed to 18°, 47° 40', and 74° 40' (though for convenience the cockpit indicators and manuals retained the original labeling).[13]

The wings were not fitted with ailerons but did possess spoilers to control rolling when the wings were at 16° and 45° angles. In addition to the spoilers, the wings were also fitted with trailing edge flaps and leading edge slats to try and give the fighter a short take-off and landing performance.[12] Although there was a gauge in the cockpit showing what position the wings were currently set, where they were in motion, and the Mach limit for each position, there was none to indicate what was the optimum wing position based on the surrounding conditions.[14]

Two tailerons controlled pitch and roll, in the latter case working in conjunction with the wings when they were not fully swept back. In addition to a fairly large vertical stabilizer (which also stored the brake parachute for landings), the MiG-23 featured a ventral fin to improve directional stability at high speeds. During take-off and landings, the fin was designed to fold sideways any time the landing gears were extended so it would not scrap against the ground.[10][12]

Engine

The MiG-23's original engine was a powerful Tumansky R-29-300 that could generate 27,500 lb (12,500 kg) of thrust, easily taking the fighter to its top speed of Mach 2.4.[15] It also had excellent acceleration, requiring just 3-4 seconds to go from idle to full power, and less than a second to ignite the afterburner.[10] In fact, the engine was so powerful that the MiG-23 could technically go faster than its placarded top speed, but doing so would cause the cockpit canopy to implode.[16] The engine's intake featured a system of louvers which took surplus bleed air for use by the plane's environmental control system to keep the avionics and pilot cool.[15]

However, like early examples of the F-4 Phantom's J-79 engine, the R-29 would generate smoke when at non-afterburn power.[10] The R-29 also ran extremely hot, which sometimes triggered false fire alarms. Moreover, the engine was only good for a couple of hundred sorties at most before requiring replacement.[17] Partly this was due to the fact that Russian engines were designed to last about 150 hours before being replaced.[18] It was also a way to make money back from export customers by selling them new engines in exchange for hard currency.[19] Getting the engine in or out of the MiG-23 could be an issue as it required the plane be pulled in half.[20]

The engine was also a weak point on early models of the MiG-23 as its mounting was not stressed for strong yaw movement. In the event the fighter went into a spin, the engine shaft could warp from the motion. This would cause the compressor blades to tear out the louvers, which would go into the turbine section and cause the turbine blades to break off, fly everywhere and destroy the engine. The problem was solved with the introduction of the R-29B-300 which was better suited to this motion.[15]

Early models of the MiG-23 also ran into the problem that the plane's fuel tank, located in the fuselage wingbox, were integral to the structure rather contained within a fuel bladder. This meant that as the structure developed hairline fractures fuel would seep out, requiring severe g-force limits until a solution could be found. Until structure quality was improved in later models, one fix was to weld a plate on the inside surface and a stiffener on the outer skin.[21]

Performance tests

Most potential enemies of the USSR and its client states have had opportunities to evaluate the MiG-23's performance. In the summer of 1977, after a political realignment by the Egyptian government, Egypt provided a number of MiG-23MSs and MiG-23BNs to the United States; these were evaluated under a pair of exploitation programs codenamed HAVE PAD and HAVE BOXER respectively. These and other MiGs, including additional MiG-23s acquired through other sources, were used as part of a secret training program known as project Constant Peg to familiarize American pilots with Soviet aircraft.[18] Additionally, a Cuban pilot flew a MiG-23BN to the U.S. in 1991, and a Libyan MiG-23 pilot also defected to Greece in 1981. In both cases, the aircraft were later repatriated.[22]

Initially, American intelligence on the MiG-23 assumed that the fighter could turn well and had reasonable acceleration capability, but testing during HAVE PAD proved this assumption to be incorrect. While its turning capability was comparable to an original F-4E Phantom, newer American fighters like the F-15 Eagle or F-4E upgraded with slats could easily out-turn the MiG-23 in a dogfight. In fact, whenever the MiG-23 approached high angle of attack it became very unstable and liable to leave controlled flight.[23][10] Conversely, the MiG-23's acceleration capability was tremendous, particularly at low altitudes (below 10,000 ft (3,000 m)) and crossing the sound barrier, where it could out-accelerate any American fighter.[23][10] The fighter's small profile gave it the advantage of being hard to spot visually as well. Overall, HAVE PAD testing determined that the MiG-23 - while a poor dogfighter - made for a good interceptor capable of performing hit-and-run attacks. Despite its limitations, in the hands of a very capable pilot the MiG-23 represented a serious threat in air combat.[23][10]

Col (ret.) John "Sax" Saxman,

4477th Test and Evaluation Squadron[24]

Test pilots who flew the MiG-23 as part of Constant Peg came to similar conclusions about the MiG-23 being a terrible maneuvering aircraft that used speed to win, and sought to teach these aspects to the frontline Tactical Air Command squadrons (nicknamed Blue Air) against whom they trained. "We taught the guys that if you were defensive with a Flogger right behind you, then you were automatically offensive, because even the worst pilot in the world would be able to deny him the shot. You would turn, he would try and turn with you, but he would never be able to turn the same corner as you," according to Col (ret.) Paco Geisler. As recalled by LtCol (USMC ret.) Lenny Bucko regarding two vs two training: "One of the MiG-23s would retreat while the other guy would come in behind you. In the training environment the Blue Air pilots would do their intercepts at 350 to 400 knots, so when they all of a sudden get this Flogger coming at Mach 1.5, it really changes the geometry of things. It blows your mind because you are not used to seeing that kind of speed."[24]

The MiG-23's speed in particular was used as a teaching aid for a couple of situations during a potential war with the Soviet Union. The first was at low altitudes to demonstrate its ability to run down any NATO or American strike aircraft (barring the late-model F-111F Aardvark), which would be attempting to go low and fast to penetrate Soviet territory. The second was to simulate the MiG-25 Foxbat, a high, fast flyer (HHF) which would be going after high-value targets such as aerial refueling or airborne early warning and control aircraft like the E-3 Sentry.[24]

The early MiG-23M series was also used to test the American Northrop F-5s captured by the North Vietnamese and sent to the former USSR for evaluation. The Russians acknowledged the F-5 was a very agile aircraft, and at some speeds and altitudes better than the MiG-23M, one of the main reasons the MiG-23MLD and MiG-29 developments were started. These tests allowed the Russians to make modifications to several of their fourth-generation aircraft. The MiG-23, however, was not designed to combat F-5s, a weakness reflected by early MiG-23 variants.[25]

Dutch pilot Leon van Maurer, who had more than 1,200 hours flying F-16s, flew against MiG-23MLs from air bases in Germany and the U.S. as part of NATO's aerial mock combat training with Soviet equipment. He concluded the MiG-23ML was superior in the vertical to early F-16 variants, just slightly inferior to the F-16A in the horizontal, and had superior BVR capability.[26] The Soviet combat manual for MiG-23M pilots claims the MiG-23M to have a slight superiority over the F-4 and Kfir, and describes combat history involving Syrian MiG-23MFs versus Israeli F-15 and F-16s, which it labels "successful". This manual also recommends tactics to be used against these fighters.[27]

Operational history

Western and Russian aviation historians usually differ in respect to combat record for their military vehicles and doctrines part due to the bias in favor of their respective national industries and academies. They also usually accept claims going along with their respective political views since usually many conflicting and contradictory reports are written and accepted by their respective historians.[28][29][30] Before recent years, with widespread use of hand portable cameras, little pictorial evidence could be published about specific losses and victories of the different combat systems, with a limited number of losses and victories confirmed by both parties.[31]

Soviet and Warsaw Pact

Because of its distinctive appearance with large air intakes on both sides of the fuselage the aircraft was nicknamed "Cheburashka" by some Soviet pilots after a popular Russian cartoon character representing a fictional animal with big ears. The nickname did not stick and was later firmly assigned to Antonov An-72/74, although to this day it is sometimes applied to different aircraft with similar exterior features, including the USAF A-10 Thunderbolt II.

The aircraft was not used in large numbers by the non-Soviet air forces of the Warsaw Pact as originally envisioned. When the MiG-23s were initially deployed, they were considered the elites of the Eastern Bloc air forces. However, very quickly the disadvantages became evident and the MiG-23 did not replace the MiG-21 as initially intended. The aircraft had some deficiencies that limited its operational serviceability and its hourly operating cost was thus higher than the MiG-21s. The Eastern Bloc air forces used their MiG-23s to replace MiG-17s and MiG-19s still in service.

By 1990, over 1,500 MiG-23s of different models were in service with the VVS and the V-PVO. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the new Russian Air Force began to cut back its fighter force, and it was decided the single-engined MiG-23s and MiG-27s were to be retired to operational storage. The last model to serve was the MiG-23P air defense variant and it was retired on 1 May 1998.[32]

When East and West Germany unified, no MiG-23s were transferred to the German Air Force, but twelve former East German MiG-23s were supplied to the US. When Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the Czechs received all the MiG-23s, which were retired in 1998. Hungary retired their MiG-23s in 1996, Poland in 1999, Romania in 2000, and Bulgaria in 2004.

The MiG-23 was the Soviet Air Force's "Top Gun"-equivalent aggressor aircraft from the late 1970s to the late 1980s. It proved a difficult opponent for early MiG-29 variants flown by inexperienced pilots. Exercises showed when well-flown, a MiG-23MLD could achieve favorable kill ratios against the MiG-29 in mock combat by using hit-and-run tactics and not engaging the MiG-29s in dogfights. Usually the aggressor MiG-23MLDs had a shark mouth painted on the nose just aft of the radome, and many were piloted by Soviet–Afghan War veterans. In the late 1980s, these aggressor MiG-23s were replaced by MiG-29s, also featuring shark mouths.[33]

- Soviet–Afghan War

Soviet MiG-23s were used over Afghanistan. Some of them were claimed to have been shot down.

Soviet and Afghan MiG-23s and Pakistani F-16s clashed a few times during the Soviet–Afghan War from 1987. Two MiG-23 were claimed shot down in air to air fight by Pakistani F-16s when crossing the border[34] (they both were not confirmed[35]) while one F-16 was shot down on 29 April 1987. Pakistani and Western[36] sources consider it a friendly fire incident but the Soviet-backed Afghan government of the time claimed that Soviet aircraft downed the Pakistani F-16 – a claim that The New York Times and the Washington Post also reported.[37][38] According to a Russian version of the event, the F-16 was shot down when Pakistani F-16s encountered Soviet MiG-23MLDs. Soviet MiG-23MLD pilots, while on a bombing raid along the Pakistani-Afghan border, reported being attacked by F-16s and then seeing one F-16 explode. It could have been downed by gunfire from a MiG whose pilot did not report the kill, because Soviet pilots were not allowed to attack Pakistani aircraft without permission.[39]

In 1988, Soviet MiG-23MLDs using R-23s (NATO: AA-7 "Apex") downed two Iranian AH-1J Cobras that had intruded into Afghan airspace. In a similar incident a decade earlier, on 21 June 1978, a PVO MiG-23M flown by Pilot Captain V. Shkinder shot down two Iranian Boeing CH-47 Chinook helicopters that had trespassed into Soviet airspace, one helicopter being dispatched by two R-60 missiles and the other by cannon fire.

- Soviet support of People's Democratic Republic of Yemen

The USSR supported the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen with Soviet Air Force MiG-23BN and MiG-25R based in Aden starting from the late Seventies. During the South Yemen Civil War in January 1986, the Soviet MiG-23BN fleet flew strikes in support of loyalist forces.[40] It is not clear if these MiG-23 were ever transferred to the South Yemeni control and later to the unified Yemeni Air Force or they always remained under Soviet control and withdrew later.[41]

Syria

- Combat against Israel (since 1973)

The first MiG-23s were supplied to Syria on 14 October 1973, when two MiG-23MSs and two MiG-23UBs were shipped in crates, aboard An-12B transports. By the time these planes could be assembled, flight-tested and their crews made combat ready, the war with Israel was over. During 1974 several Syrian MiG-23s were lost in accidents. The process of making the MiG-23 operational was complex and difficult, and only eight were operational by 1974. The first MiG-23s to see combat were export variants with many limitations. For example, the MiG-23MS lacked a radar warning receiver. In addition, compared to the MiG-21, the aircraft was mechanically complex and expensive and also less agile. Early export variants also lacked many "war reserve modes" in their radars, making them vulnerable against electronic countermeasures (ECM), at which the Israelis were especially proficient.

On 13 April 1974, after almost 100 days of artillery exchanges and skirmishes along the Golan Heights, Syrian helicopters delivered commandos to attack the Israeli observation post at Jebel Sheikh. This provoked heavy clashes in the air and on the ground for almost a week. On 19 April 1974, Captain al-Masry, flying a MiG-23MS on a weapons test mission, spotted a group of IAF F-4Es and shot two of them down after firing three missiles. He was about to attack another F-4 with cannon fire, but was shot down by friendly fire from a SAM battery.[42] Due to this success, an additional 24 MiG-23MS interceptors, as well as a similar number of MiG-23BN strike variants, were delivered to Syria during the following year. In 1978 deliveries of MiG-23MFs started and two squadrons were equipped with them.

The MiG-23MF, MiG-23MS and MiG-23BN were used in combat by Syria over Lebanon between 1981 and 1985. On 26 April 1981, Syria claimed that two Israeli A-4 Skyhawks attacking a camp in Sidon were shot down by two MiG-23MSs.[42] However, Israel does not report any loss of aircraft from this incident and no loss of aircraft was reported on that date. Russian historian Vladimir Ilyin writes that the Syrians lost six MiG-23MFs, four MiG-23MSs and a few MiG-23BNs in June 1982. One more MiG-23 fighter was lost in July. The Israelis also claimed that they shot down two MiG-23s in 1985, which the Syrians deny. Overall, 11–13 Syrian MiG-23 fighter variants were lost in air combat from 1982 to 1985. Israel confirms only loss of BQM-34 Firebee which was downed by Syrian MiG-23MF on 6 June 1982.

At the end of April 2002 Syrian MiG-23ML shot down an Israeli UAV with an air-to-air missile near As-Suwayda.[43]

- Syrian Civil War

A former Syrian Air Force MiG-23MS became iconic of the Siege of Abu al-Duhur Airbase: on 7 March 2012, Syrian rebels used a 9K115-2 Metis-M anti-tank guided missile to hit the derelict MiG. Later, in March 2013 they entered in the base, showing the worn out and damaged MiG. Finally, in May 2013, the Syrian Air Force bombed it to completely destroy the wreck.[44]

Syrian MiG-23BNs bombed the city of Aleppo on 24 July 2012, becoming the first use of fixed-wing aircraft for bombing in the Syrian civil war.[45][46][47]

On 13 August 2012, a Syrian MiG-23BN was reportedly shot down by the rebels of the Free Syrian Army near Deir ez-Zor, although the government claimed that it went down due to technical difficulties.[48]

Since then, Syrian Air Force MiG-23s together with different Syrian Air Force fighter jets have regularly been spotted performing attack runs on Syrian insurgents, who have claimed different MiGs being shot down or destroyed on the ground on different occasions.

On 23 March 2014, one Syrian MiG-23 was shot down after being hit by an AIM-9 Sidewinder fired by a Turkish F-16 in the vicinity of the Syrian town of Kessab. The pilot ejected safely and was recovered by friendly forces. Turkish sources said the fighter violated Turkish airspace and it was downed after several radio warnings while approaching the border. Another Syrian MiG-23 returned to Syria after trespassing into Turkish airspace.[49]

On 15 June 2017, one Jordanian Selex ES Falco UAV was shot down by a Syrian MiG-23MLD in the vicinity of the Syrian town of Derra. On 16 June, another Selex ES Falco was shot down by MiG-23ML both using R-24R missiles.[50]

Iraq

- Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988)

The MiG-23 took part in the Iran–Iraq War and was used in both air-to-air and air-to-ground roles. The reports about performance in air combat are mixed – some authors claim that Iraqi MiG-23s had some victories and several losses against Iranian F-14s, F-5s and F-4s.

- Iranian Air Force Colonel, Mohammed-Hashem All-e-Agha was shot down by an Iraqi MiG-23ML while flying his F-14A on 11 August 1984. [51]

- Iranian Air Force Colonel Abdolbaghi Darvish was shot down by an Iraqi MiG-23ML while flying his Fokker F27-600 on 20 February 1986. All 49 crew members and passengers were killed.[52] The aircraft was carrying a delegation of military and government officials on a mission.

- Iranian Air Force Captain Bahram Ghanei was shot down by a MiG-23ML while flying his F-14A on 17 January 1987.[53][54]

- Known Iraqi MiG-23 fighter pilot was Captain Omar Goben. He shot down at least one F-5E and one F-4E with a MiG-23, and two F-5Es and one F-4E with a MiG-21.[55][56]

According to researcher Tom Cooper, Iranian F-14s caused exceptionally heavy losses to the MiG-23s (most of them bombers, model MiG-23BN) early in the war, much to the disappointment of the Iraqi Air Force, which thought that the Soviet fighter would be a match for the Tomcat.[57] During the Iran-Iraq War at least 58 MiG-23s are claimed to be shot down by F-14s (15 of these are confirmed according to Cooper),[58] and 20 MiG-23s are claimed by F-4s (16 confirmed according to Cooper).[59] According to official Iraqi data only 29 MiG-23s were lost during the entire war (between 20 and 28 of them were shot down by AAA, enemy fighters or friendly fire).[60]

- Iraqi MiG-23MS/MFs (fighters) were used in the first half of the war scoring no less than 8 kills while suffering 2 MiG-23MS and 4 MiG-23MF losses.

- MiG-23MLs (fighters) were used in the second half of the war. They possibly scored 7 kills (including 2 F-14) while possibly suffering 3 losses.[61][62][63][64]

- MiG-23BNs (ground-attack variant) were successfully used against ground targets. On 22 September 1980, BNs were used in first combat sorties against Iran. Two F-4 Phantoms were destroyed at Mehrabad Air Base in BNs attack. However up to 22 MiG-23BNs were downed by Iranian interceptors during the war. According to other sources, 16 BNs were lost during war, 13 of them in combat.[60][64][65]

- According to Iranian sources, four MiG-23BNs were shot down by F-14s on 29 October 1980, but the victory was not confirmed.[66]

- Kuwait Invasion and Gulf War (1990–1991)

On 2 August 1990, the Iraqi Air Force supported the invasion of Kuwait with MiG-23BN and Su-22 aircraft as the main strike assets. A number of Iraqi aircraft and helicopters were claimed shot down by Kuwaiti air defense MIM-23 Hawk SAM sites, among them a MiG-23BN.[67]

Iraqi documents captured after the invasion of Iraq revealed that they possessed 127 MiG-23s, included 38 MiG-23BNs and 21 MiG-23 trainers, at the start of Operation Desert Storm.[68] During the Gulf War, the United States Air Force reported downing eight Iraqi MiG-23s with F-15s.[69] Iraqi documents confirm the total destruction of 43 MiG-23s from all causes, with another 10 damaged and 12 others fleeing to Iran. This left Iraq with just 63 MiG-23s after the war, including 18 Mig-23BNs and 12 trainers.[68]

The United States stated that the losses of the F-16Cs were caused by 2K12 Kub and S-125 Neva/Pechora surface-to-air missiles rather than enemy aircraft.[70] Also, no Tornado loss is attributed to enemy aircraft as per the Royal Air Force and the Italian Air Force.[71][72]

- No Fly Zone and invasion of Iraq (1991–2003)

On 17 January 1993, a USAF F-16C destroyed an Iraqi MiG-23 with an AMRAAM missile.[73] On 9 September 1999, a lone MiG-23 crossed the no-fly zone heading towards a flight of F-14s. One F-14 fired an AIM-54 Phoenix at the MiG but missed and the MiG headed back north.

In 2003, during Operation Iraqi Freedom, the entire Iraqi Air Force remained grounded with several airframes found by US and allied forces around the Iraqi air bases in derelict condition after the invasion. The invasion marked the end of Iraqi service for the MiG-23.

Cuba

- Cuba in Angola

Cuban MiG-23MLs and South African Mirage F1 pilots had several encounters during the Cuban intervention in Angola, one of which resulted in severe damage to a Mirage F1.

On 27 September 1987, during Operation Moduler, two MiG-23 pilots surprised a pair of Mirages and fired missiles: Alberto Ley Rivas engaged a Mirage flown by Capt Arthur Douglas Piercy with a pair of R-23Rs (some sources say a R-60), while the other Cuban pilot fired a single R-60 at a Mirage flown by Captain Carlo Gagiano. Although the missiles homed on the Mirages, only one R-23R exploded close enough to cause damage to the landing hydraulics of Capt Piercy's Mirage (and, according to some accounts, the aircraft's drag chute). The damage likely contributed to the Mirage veering off the runway on landing, after which the nose gear collapsed. The nose hit the ground so hard that Piercy's ejection seat fired. As a result of this ground level ejection, Piercy was paralyzed. The aircraft was written off, but a large portion of the airframe and components were used to repair another accident damaged Mirage F-1 and return it to service. In total, the Cubans claimed 6 air victories with the MiG-23 (1 destroyed, 1 damaged and 4 were unconfirmed).[74]

FAPLA MiG-23s outclassed SAAF Mirage F-1CZ and F-1AZ fighters in terms of power/acceleration, radar/avionics capabilities, and air-to-air weapons. The MiG-23's R-23 and R-60 missiles gave FAPLA pilots the ability to engage SAAF aircraft from most aspects. The SAAF, hobbled by an international arms embargo, was forced to carry an obsolescent version of the French Matra R.550 Magic missile or early-generation V-3 Kukri missiles, which had limited range and performance relative to the R-60 and R-23. Despite these limitations, SAAF pilots were able to vector within the firing envelope and fire AAMs at MiG-23s (gun camera shots evidence this).[75] The missiles either missed or exploded ineffectually behind in the tail plume rather than homing on the hot airframe.

UNITA rebels, opposing Cuban/MPLA forces, shot down a number of MiG-23s with American-supplied FIM-92 Stinger MANPADS missiles. South African ground forces shot down a MiG-23, which was prosecuting a raid on the Calueque Dam, by using the Ystervark (porcupine) 20 mm AA gun.[76]

Libya

.jpg)

Libya received a total of 54 MiG-23MS and MiG-23Us between 1974 and 1976, followed by a similar number of MiG-23BNs. Many of these were immediately put into storage, but at least 20 MiG-23MSs and MiG-23UBs entered service with the 1023rd Squadron and 1124th Squadron.

One Libyan MiG-23MS was shot down by an Egyptian MiG-21 fighter during and immediately after the Libyan–Egyptian War in 1977 while supporting a strike on the airfield at Mersa-Matruh, forcing the remaining MiG to abort the mission. In one skirmish in 1979, two LARAF MiG-23MS engaged two EAF MiG-21MF which had been upgraded to carry Western air-to-air missiles such as the AIM-9P3 Sidewinder. The Libyan pilots made the mistake of trying to outmaneuver the more nimble Egyptian MiG-21s, and one MiG-23MS was shot down by Maj. Sal Mohammad with an AIM-9P3 Sidewinder missile, while the other used its superior speed to escape.[77]

On 18 July 1980, the wreckage of an LARAF MiG-23MS was found on the northern side of Mount Sila, in the middle of the Italian province of Calabria. The deceased pilot, Captain Ezzedin Fadhel Khalil, was found still strapped to his ejection seat.[78][79]

Libyan MiG-23s were employed during the Chadian–Libyan conflict performing different roles in the 1980s. On 5 January 1987, a Libyan MiG-23 was shot down[80] and few months later, on 5 September 1987, Chadian forces performed a land raid against Maaten al-Sarra Air Base in Libya, destroying several Libyan aircraft on the ground, among them, three MiG-23s.[81]

Two Libyan MiG-23MS fighters were shot down by U.S. Navy F-14s in the Second Gulf of Sidra incident in 1989.

- Libyan Civil War

In the 2011 Libyan civil war, Libyan Air Force MiG-23s were used to bomb rebel positions.[82] On 15 March 2011, a rebel website reported that opposition forces started using a captured MiG-23 and a helicopter to sink 2 loyalist ships and bomb some tank positions.[83]

On 19 March 2011, a MiG-23BN of the Free Libyan Air Force was shot down over Benghazi by its own air defenses, who mistook it for a loyalist aircraft.[84] The pilot was killed after he ejected too late.[85]

On 26 March 2011, five MiG-23s together with two Mi-35 helicopters were destroyed by the French Air Force while parked at Misrata airport, early reports misidentified the fixed wing aircraft as G-2 Galebs.[86]

On 9 April, a rebel MiG-23 was intercepted over Benghazi by NATO aircraft and escorted back to its base for violating the UN no-fly zone.[87]

A limited number of MiG-23's which survived the 2011 Libyan civil war and NATO bombings were involved in air strikes between the opposing Libyan House of Representatives and the rival General National Congress during the Second Libyan Civil War with both parties controlling a limited number of aircraft.[88]

On 23 March 2015, a New General National Congress operated MiG-23UB was shot down while bombing Al Watiya airbase, controlled by the Libyan House of Representative probably with an Igla-S MANPADS. Both pilots were killed.[89] At the beginning of 2016, Libyan House of Representatives forces controlled three airworthy MiG-23s among other aircraft, two MiG-23MLA and one MiG-23UB. They were all lost in three separate occasions with a first MiG-23MLA, serial 6472, lost near Benina airbase on 4 January, after an airstrike,[90] the second MiG-23MLA, serial 6132, lost on 8 February while conducting air strikes against Islamic State near Derna[91] and the MiG-23UB, serial 7834, lost on 12 February 2016 while operating west of Benghazi, claimed shot down by the Islamic State with the official government attributing the loss to anti aircraft artillery.[92][93] In all the occasions the aircrews ejected while the cause of the first two crashes remained debated between hostile fire and mechanical causes.

On 28 February 2016, a MiG-23MLA serial 6453 was restored to flying status after several years,[94] becoming the only MiG-23 in service with the Libyan Air Force as of March 2016, performing missions against enemy positions and vehicles since March 2016.[95][96]

In the following weeks, both the Libyan Air Force and the opposing Libyan Dawn Air Force, restored a number of MiG-23BN, MiG-23ML and MiG-23UB to flying status and they were recorded while flying over Libyan skyes and striking enemy positions.[97][98]

On 6 December 2019, a Libyan National Army (LNA) MiG-23MLD was shot down by forces loyal to the Government of National Accord (GNA). In the ongoing Libyan Civil War both parties are pushing back to service stored airframes after repairs with foreign assistance. The jet, serial 26144, was restored using the wings of two different airframes and became flyable again in August 2019, after around 20 years of storage.[99] The jet was hit over the Yarmouk frontline in southern Tripoli and crashed in Al Zawiya city and the pilot, Amer Jagem was detained after ejecting. A video emerged showing the aircraft diving for attack with soldiers on the ground firing a Strela-2M MANPADS in response. The LNA reported they lost a MiG-23 due to technical fault, denying it crashed due to enemy fire.[99][100][101]

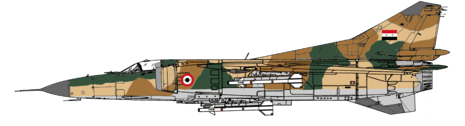

Egypt

Egypt became one of the first export customers when in 1974 bought eight MiG-23MS interceptors, eight MiG-23BN strikers and four MIG-23U trainers, concentrating them into a single regiment based at Mersa Matruh. By 1975 all Egyptian MiG-23s had been withdrawn from active duty and placed in storage due to the Egyptian foreign policy shifting towards the West and thus losing USSR support.

In 1978 China purchased two MiG-23MS interceptors, two MiG-23BNs, two MiG-23Us, ten MiG-21MFs, and ten KSR-2 (AS-5 Kelt) air-to-surface missiles in exchange for spare parts and technical support for the Egyptian fleet of Soviet-supplied MiG-17 Frescos and MiG-21s. The Chinese used the aircraft as the basis for their J-9 project, which never ventured beyond the research phase.

Some time later the remaining six MiG-23MS examples and six MiG-23BNs, as well as 16 MiG-21MFs, two Sukhoi Su-20 Fitters, two MiG-21Us, two Mil Mi-8 Hips and ten KSR-2 were purchased for the Foreign Technology Division, a special department of the USAF, responsible for evaluating adversary technologies. These were exchanged for weapons and spares support, including AIM-9J/P Sidewinder missiles, which were installed on remaining Egyptian MiG-21s.

Ethiopia

MiG-23s supplied by the Soviet Union to Mengistu Haile Mariam's Derg were heavily used by the Ethiopian Air Force against the array of rebel guerillas fighting the government during the Ethiopian Civil War. According to a 1990 Human Rights Watch report, the attacks, often using napalm or phosphorus and cluster munitions, were not only aimed at the rebels, but against civilian populations (in both Eritrea and Ethiopia) and humanitarian convoys in a deliberate fashion.[102]

Ethiopian MiG-23s were used in ground attack and strike missions during the border war with Eritrea from May 1998 to June 2000, even striking targets at the airport in the Eritrean capital city, Asmara on several occasions.[103][104] Three Ethiopian MiG-23BNs were claimed shot down by Eritrean MiG-29s.[105]

India

- Kargil War (1999)

On 26 May, the Indian forces started air strikes during the Kargil War. Flying from the Indian airfields of Srinagar, Avantipur and Adampur, MiG-23BN, joined the other Indian strike aircraft, MiG-21s, MiG-27s, Jaguars and Mirage 2000 in striking the enemy positions.[106]

Variants

First-generation

- Ye-231

- ("Flogger-A") was the prototype built for testing, and it lacked the sawtooth leading edge that later appeared on all MiG-23/-27 models. This experimental model was the common basic design that both the MiG-23/-27 and Sukhoi Su-24 were based on, but the Su-24 experienced much greater modification.

- MiG-23

- ("Flogger-A") was the pre-production model that lacked the hardpoints on later production versions, but the sawtooth leading edge appeared on this model, and it was also armed with guns. This model marked the divergence of the MiG-23/-27 and Su-24 from their common ancestor.

- MiG-23S

- ("Flogger-A") was the initial production variant. Only around 60 were built between 1969 and 1970. These aircraft were used for both flight and operational testing. The MiG-23S had an improved R-27F2-300 turbojet engine with a maximum thrust of 98 kN (22,000 lbf). As the Sapfir-23 radar was delayed, the aircraft were installed with the S-21 weapons control system with the RP-22SM radar—basically the same weapons system as in the MiG-21MF/bis. A twin-barreled 23 mm GSh-23L gun with 200 rounds of ammunition was fitted under the fuselage. This variant suffered from various teething problems and was never fielded as an operational fighter.

- MiG-23SM

- ("Flogger-A") was the second pre-production variant, which was also known as the MiG-23 Type 1971. It was considerably modified compared to the MiG-23S: it had the full S-23 weapons suite, featuring a Sapfir-23L radar coupled with Vympel R-23R (NATO: AA-7 "Apex") BVR missiles. It also had a further improved R-27F2M-300 (later redesignated Khatchaturov R-29-300) engine with a maximum thrust of 118 kN (26,500 lbf). The modified "type 2" wing had an increased wing area and a larger sawtooth leading edge. The slats were deleted and wing sweep was increased by 2.5 degrees; wing positions were changed to 18.5, 47.5 and 74.5 degrees, respectively. The tail fin was moved further aft, and an extra fuel tank was added to the rear fuselage, as in the two-seat variant (see below). Around 80 examples were manufactured. The overall reliability was increased over the previous variant, but the "Sapfir" radar still proved to be immature.

- MiG-23M

- ("Flogger-B") This variant first flew in June 1972. It was the first truly mass-produced version of the MiG-23, and the first VVS fighter to feature look-down/shoot-down capabilities (although this capability was initially very limited). The wing was modified again and now featured leading-edge slats. The Tumansky R-29 (R-29A) engine was now rated for 123 kN (27,600 lbf). It finally had the definitive sensor suite: an improved Sapfir-23D (NATO: 'High Lark') radar, a TP-23 infra-red search and track (IRST) sensor and an ASP-23D gunsight. The "High Lark" radar had a detection range of some 45 km against a high-flying, fighter-sized target. It was not a true Doppler radar but instead utilized the less effective "envelope detection" technique, similar to some radars on Western fighters of the 1960s.

- MiG-23MF

- ("Flogger-B") This was an export derivative of the MiG-23M originally intended to be exported to Warsaw Pact countries, but it was also sold to many other allies and clients, as most export customers were dissatisfied with the rather primitive MiG-23MS. It actually came in two versions. The first one was sold to Warsaw Pact allies, and it was essentially identical to Soviet MiG-23M, with small changes in "identify friend or foe" (IFF) transponders and communications equipment. The second variant was sold outside Eastern Europe and it had a different IFF and communications suite (usually with the datalink removed), and downgraded radar, which lacked the electronic counter-countermeasure (ECCM) features and modes of the baseline "High Lark". This variant was more popular abroad than the MiG-23MS and considerable numbers were exported, especially to the Middle East.

- The infrared system had a detection range of around 30 km against high-flying bombers, but less for fighter-sized targets. The aircraft was also equipped with a Lasur-SMA datalink. The standard armament consisted of two radar- or infrared-guided Vympel R-23 (NATO: AA-7 "Apex") BVR missiles and two Molniya R-60 (NATO: AA-8 "Aphid") short-ranged infrared missiles. From 1974 onwards, double pylons were installed for the R-60s, enabling up to four missiles to be carried. Bombs, rockets and missiles could be carried for ground attack. Later, compatibility for the radio-guided Kh-23 (NATO: AS-7 "Kerry") ground-attack missile was added. Most Soviet MiGs were also wired to carry tactical nuclear weapons. Some 1300 MiG-23Ms were produced for the VVS and Soviet Air Defense Forces (PVO Strany) between 1972 and 1978. It was the most important Soviet fighter type from the mid-to-late 1970s.

- MiG-23U

- ("Flogger-C") The MiG-23U was a twin-seat training variant. It was based on the MiG-23S, but featured a lengthened cockpit with a second crew station behind the first. One forward fuel tank was removed to accommodate an extra seat; this was compensated for by adding a new fuel tank in the rear fuselage. The MiG-23U had the S-21 weapon system, although the radar was later mostly removed. During its production run, both its wings and engine were improved to the MiG-23M standard. Production began at Irkutsk in 1971 and eventually converted to the MiG-23UB.

- MiG-23UB

- ("Flogger-C") Very similar to MiG-23U except that the Tumansky R-29 turbojet engine replaced the older R-27 installed in the MiG-23U. Production continued until 1985 (for the export variant). A total of 769 examples were built, including conversions from the MiG-23U.

- MiG-23MP

- ("Flogger-E") Similar to the MiG-23MS (described below), but produced in much fewer numbers and was never exported. Virtually identical to MiG-23MS except the addition of a dielectric head above the pylon, which was often associated with the ground-attack versions—for which it might have been a developmental prototype.

- MiG-23MS

- ("Flogger-E") This was an export variant, as the '70s MiG-23M was considered too advanced to be exported to Third World countries. It was otherwise similar to MiG-23M, but it had the S-21 standard weapon system, with a RP-22SM (NATO: "Jay Bird") radar in a smaller radome, and the IRST was removed. Obviously, this variant had no BVR capability, and the only air-to-air missiles it was capable of using were the R-3S (NATO: AA-2a "Atoll") and R-60 (NATO: AA-8 "Aphid") IR-guided missiles and the R-3R (NATO: AA-2d "Atoll") semi-active radar homing (SARH) missile. The avionics suite was very basic. This variant was produced between 1973 and 1978 and exported principally to North Africa and the Middle East.

Second-generation

- MiG-23P

- ("Flogger-G") This was a specialized air-defense interceptor variant developed for the PVO Strany. It had the same airframe and powerplant as the MiG-23ML, but there is a cut-back fin root fillet instead of the original extended one on other models. Its avionics suite was improved to meet PVO requirements and mission profiles. Its radar was the improved Sapfir-23P, which could be used in conjunction with the gunsight for better look-down/shoot-down capabilities to counter increasing low-level threats like cruise missiles. The IRST, however, was absent. The autopilot included a new digital computer, and it was linked with the Lasur-M datalink. This enabled ground-controlled interception (GCI) ground stations to steer the aircraft towards the target; in such an intercept, all the pilot had to do was control the engine and use the weapons. The MiG-23P was the most numerous PVO interceptor in the 1980s. Around 500 aircraft were manufactured between 1978 and 1981. The MiG-23P was never exported and served only within the PVO in Soviet service.

- MiG-23bis

- ("Flogger-G") Similar to the MiG-23P except the IRST was restored and the cumbersome radar scope was eliminated because all of the information it provided could be displayed on the new head-up display (HUD).

- MiG-23ML

- The early "Flogger" variants were intended to be used in high-speed missile attacks, but it was soon noticed that fighters often had to engage in more stressful close-in combat. Early production aircraft had actually suffered cracks in the fuselage during their service career. Maneuverability of the aircraft was also criticized. A considerable redesign of the airframe was performed, resulting in the MiG-23ML (L – lightweight), which made it in some ways a new aircraft. Empty weight was reduced by 1250 kg, which was achieved partly by removing a rear fuselage fuel tank. Aerodynamics were refined for less drag. The dorsal fin extension was removed. The lighter weight of the airframe resulted in a different sit on the ground, with the aircraft appearing more level when at rest compared to the nose-high appearance of earlier variants. This has led to a belief that the undercarriage was redesigned for the ML variant, but it is identical to earlier variants. The airframe was now rated for a g-limit of 8.5, compared to 8 g for the early generation MiG-23M/MF "Flogger-B". A new engine model, the R-35F-300, now provided a maximum dry thrust of 84 kN (18,800 lbf), and 127 kN (28,700 lb) with afterburner. This led to a considerable improvement in maneuverability and thrust-to-weight ratio. The avionics set was considerably improved as well. The S-23ML standard included Sapfir-23ML radar and TP-23ML IRST.[107] The new radar was more reliable and a had maximum detection range of about 65 km against a fighter-sized target (25 km in look-down mode). The navigation suite received a new, much improved autopilot. New radio and datalink systems were also installed. The prototype of this variant first flew in 1976 and production began 1978.

- MiG-23MLA

- ("Flogger-G") The later production variant of the "ML" was redesignated the "MLA". Externally, the "MLA" was identical to "ML". Internally, the 'MLA' had an improved radar with better ECM resistance, which made co-operative group search operations possible as the radars would now not jam each other. It also had a new ASP-17ML HUD/gunsight, and the capability to fire improved Vympel R-24R/T missiles. Between 1978 and 1982, around 1,100 "ML/MLA"s were built for both the Soviet Air Force and export customers. As with the MiG-23MF, there were two different MiG-23ML sub-variants for export: the first version was sold to Warsaw Pact countries and was very similar to Soviet aircraft. The second variant had downgraded radar and it was sold to Third World allies.

- MiG-23MLD

- ("Flogger-K") The MiG-23MLD was the ultimate fighter variant of the MiG-23. The main focus of the upgrade was to improve manoeuvrability, especially during high angles of attack (AoA). The pitot boom was equipped with vortex generators, and the wing's notched leading edge roots were 'saw-toothed' to act as vortex generators as well. The flight-control system was modified to improve handling and safety in high-AoA maneuvers. Significant improvements were made in avionics and survivability: the Sapfir-23MLA-II featured improved modes for look-down/shoot-down and close-in fighting. A new SPO-15L radar warning receiver was installed, along with chaff/flare dispensers. The new and very effective Vympel R-73 (NATO: AA-11 "Archer") short-range air-to-air missile was added to inventory. No new-build "MLD" aircraft were delivered to the VVS, as the more advanced MiG-29 was about to enter production. Instead, all Soviet "MLD"s were former "ML/MLA" aircraft modified to "MLD" standard. Some 560 aircraft were upgraded between 1982 and 1985. As with earlier MiG-23 versions, two distinct export variants were offered. Unlike Soviet examples, these were new-build aircraft, though they lacked the aerodynamic refinements of Soviet "MLD"s; 16 examples were delivered to Bulgaria, and 50 to Syria. These were the last single-seat MiG-23 fighters made, and the last example rolled off the production line in December 1984.

Ground-attack variants

- MiG-23B

- ("Flogger-F") The requirement for a new fighter-bomber had become obvious in the late 1960s, and the MiG-23 appeared to be suitable type for such conversion. The first prototype of the project, "32–34", flew for the first time on 20 August 1970. The MiG-23B had a redesigned forward fuselage, but was otherwise similar to the MiG-23S. The pilot seat was raised to improve visibility, and the windscreen was armoured. The nose was flat-bottomed and tapered down. There was no radar; instead it had a PrNK Sokol-23 ground attack sight system, which included an analogue computer, a laser rangefinder and the PBK-3 bomb sight. The navigation suite and autopilot were also improved to provide more accurate bombing. It retained the GSh-23L gun, and its maximum warload was increased to 3000 kg by strengthening the pylons. Survivability was improved by an electronic warfare (EW) suite and inert gas system in the fuel tanks to prevent fire. The first prototype had a MiG-23S type wing, but subsequent examples had the larger "type 2" wing. Most importantly, instead of an R-29 variant, aircraft was powered by the Lyulka AL-21 turbojet with a maximum thrust of 113 kN (25,400 lbf). The production of this variant was limited, however, as the supply of AL-21 engines was needed for the Sukhoi Su-17 and Su-24 production lines. In addition, this engine was not cleared for export. Only three MiG-23B prototypes and 24 production aircraft were produced in 1971–72.

- MiG-23BK

- ("Flogger-H") These were exported to Warsaw Pact countries—but not to Third World customers—and thus had the PrNK-23 navigation and attack system. Additional radar warning receivers were also mounted on the intakes.

- MiG-23BN

- ("Flogger-H") Produced since 1973, the MiG-23BN was based on MiG-23B, but had the same R-29-300 engine as contemporary fighter variants. They were also fitted with "type 3" wings. There were other minor changes in electronics and equipment, and some changes were made during its long production run. Serial production lasted until 1985, with 624 built. Most of them were exported, as the Soviets always viewed it as an interim type and only a small number served in Frontal Aviation regiments. As usual, a downgraded version was sold to Third World customers. This variant proved to be fairly popular and effective. The most distinctive identifying feature between the MiG-23B and MiG-23BN was that the former had the dielectric head just above the pylon, which was removed from the MiG-23BN. In India, the last MiG-23BNs were flown by 221 Squadron (Valiants) of Indian Air Force and were decommissioned on 6 March 2009. Wing Commander Tapas Ranjan Sahu, was the last pilot to land the MiG-23BN on that day.

- MiG-23BM

- ("Flogger-D") This was a MiG-23BK upgrade, with the PrNK-23M replacing the original PrNK-23, and a digital computer replacing the original analog computer. Introduced into service as the MiG-27.

- MiG-23BM experimental aircraft

- ("Flogger-D") The MiG-23 ground-attack versions had too much "fighter heritage" for an attack aircraft, and a new design with more radical changes was developed (later to be re-designated as the MiG-27). The MiG-23BM experimental aircraft served as a predecessor to the MiG-27 and it differs from the standard MiG-23BM and other MiG-23 models in that its dielectric heads were directly on the wing roots, instead of on the pylons.

- MiG-27

- (NATO: "Flogger-D") Introduced in 1975, simplified ground-attack version with simple pitot air intakes, no radar and a simplified engine with two position afterburner nozzle.

Proposed variants and upgrades

- MiG-23R

- was a proposed reconnaissance variant; the project was never finished.

- MiG-23MLGD

- "MLG" and "MLS" were further fighter upgrades with new radar and EW equipment, partly the same as in MiG-29; these variants were also fitted with helmet-mounted sights and were basically MiG-23MLD subvariants. They were abandoned in favor of the then ongoing MiG-29 program.

- MiG-23K

- was a carrier-borne fighter variant based on the MiG-23ML.

- MiG-23A

- was a multi-role variant based on the "K". However, cancellation and subsequent redesign of the Soviet aircraft carrier project also caused cancellation of the MiG-23A and MiG-23K variants and sub-variants. It was planned to develop the MiG-23A into three different sub-variants:

- MiG-23AI

- The MiG-23AI was to be a dedicated fighter.

- MiG-23AB

- The MiG-23AB was to be an attack-dedicated variant.

- MiG-23AR

- MiG-23AR a dedicated reconnaissance variant.

- MiG-23MLK

- Planned to be powered by either two new R-33 engines or one R-100.

- MiG-23MD

- Was basically a MiG-23M fitted with a Saphir-23MLA-2.

- MiG-23ML-1

- MiG-23-98

- In the late 1990s, Mikoyan, following their successful MiG-21 upgrade projects, offered an upgrade which featured new radar, new self-defense suite, new avionics, improved cockpit ergonomics, helmet-mounted sight, and the capability to fire Vympel R-27 (NATO: AA-10 "Alamo") and Vympel R-77 (NATO: AA-12 "Adder") missiles. The projected cost was around US$1 million per aircraft. Smaller upgrades were also offered, which consisted of only improving the existing Sapfir-23 with newer missiles and upgrades of other avionics. Airframe life extension was offered as well.

- MiG-23-98-2

- An export upgrade including the "Saphir" radar fitted to their MiG-23MLs; this radar upgrade allows the Angolan MiG-23s to fire new types of air-to-air and air-to-ground weapons. This radar upgrade seems to be the same offered as part of the radar upgrade.

- MiG-23LL

- (flying laboratory) MiG-23s and MiG-25s were used as the first jet fighter platforms to test a new in-cockpit warning system with a prerecorded female voice to inform pilots about various flight parameters. A female voice was chosen specifically to provide a clear and intuitive distinction between communications from the ground and the messages from internal systems, since ground communications virtually always came in male voice in Soviet service. The idea proved successful for many reasons besides the original one.

Operators

Current operators

- National Air Force of Angola; 22 MiG-23ML/UB/MLD in service

- Cuban Air Force; 24 MiG-23ML/MF/BN/UB in service. One crashed in February 2019.

- DR Congo Air Force; 2 MiG-23s, One single-seat and one twin-seat

- Ethiopian Air Force; 10 MiG-23BN/UBs in service for ground attack role. The interceptor variant, MIG-23ML, was withdrawn from service.

- Military of Kazakhstan. 2 units of training Mig-23UB, as of 2018.

- Libyan Air Force; initially at least five MiG-23ML/UB in service, split among different factions. Four lost. Only one in service with the New General National Congress,[95] while others (e.g. serial 453) may have been made airworthy by both factions.[108]

- North Korean Air Force; 56 MiG-23ML/UBs in service

- Sudanese Air Force; 3 MiG-23MS/UBs in service. Four were refurbished locally in 2016, after nearly 20 years in storage. One lost during testing.[109]

- Syrian Air Force; 90 MiG-23MS/MF/ML/MLD/BN/UB airframes before the Syrian Civil War.

Former operators

.svg.png)

- Afghan Air Force. MiG-23BN/UBs may have served with the Afghan Air Force from 1984. It is unclear whether these were merely Soviet aircraft wearing Afghan colors.

- Algerian Air Force. First 40 arrived in 1979.[110]

.svg.png)

- Belarus Air Force.

- Bulgarian Air Force. A total of 90 MiG-23s served the Bulgarian Air Force from 1976 to their withdrawal from service in 2004. The exact count is: 33 MiG-23BN, 12 MiG-23MF, 1 MiG-23ML, 8 MiG-23MLA, 21 MiG-23MLD and 15 MiG-23UB.

- Cote d'Ivoire Air Force:[111]

- Czech Air Force. The MiGs were retired in 1994 (BN, MF version) and 1998 (ML, UB variant).

- Czechoslovakian Air Force. MiG-23s were transferred to the Czech Republic.

- East German Air Force; transferred to (West) German Air Force. The German Air Force gave two MiG-23s to the United States Air Force and one to a museum in Florida, the others were given away to others states or scrapped.

- Egyptian Air Force. Used until Egypt turned towards Western Governments. Six MiG-23BN/MS/Us were sent to China in exchange for military hardware; China used them to reverse engineer the MiG-23 as the Q-6 but since the Chinese could not reverse engineer the R-29 and build a reliable turbofan, the only MiG-23 elements that were used ended in the J-8II. At least eight were transferred to USA for evaluation.

- German Air Force; In 1990 the West German Air Force inherited 18 MiG-23BNs, 9 MiG-23MFs, 28 MiG-23MLs, 8 MiG-23UBs from East Germany.

- Hungarian Air Force; 16 MiG-23s served and were withdrawn in 1997; the exact count is: 12 MiG-23MFs and four MiG-23 UBs (one of them was purchased in 1990 from the Soviet Air Force).

- Indian Air Force. The MiG-23BN ground attack aircraft was phased out on 6 March 2009 and the MiG-23MF air defence interceptor phased out in 2007. 14 MiG 23UB trainers in service according to "World Air Forces 2020"

- 12 Mig-23s flown over from Iraq in 1991 in storage.

.svg.png)

- Iraqi Air Force. Used until the fall of Saddam Hussein

.jpg) Kyrgyzstan MiG-23 on display in Tokmok.

Kyrgyzstan MiG-23 on display in Tokmok. .svg.png)

- Libyan Air Force; had 130 MiG-23MS/ML/BN/UBs in service (most in storage) prior to the 2011 Libyan civil war. What remains has been passed on to the successor government.

- Polish Air Force. A total of 36 MiG-23MF single-seaters and six MiG-23UB trainers were delivered to the Polish Air Force between 1979 and 1982. The last of them were withdrawn in September 1999. During the period four planes were lost in accidents.

- Namibian Air Force; had two MiG-23 aircraft in service.[112]

- Romanian Air Force. A total of 46 MiG-23 served from 1979 until 2001 and were withdrawn in 2003; the exact count is: 36 MiG-23MF and 10 MiG-23 UB.

- Russian Air Force. Approximately 500, all in reserve.

- Somali Air Force;

- Military of Turkmenistan.

- Passed on to successor states.

- Soviet Air Force

- Soviet Anti-Air Defence

- Sri Lanka Air Force; one MiG-23UB trainer used only for training purposes for their MiG-27 fleet[113]

- Uganda People's Defence Force

- Ukrainian Air Force

- Military of Uzbekistan

- Military of Zambia.

- Air Force of Zimbabwe ; given by Libya.

Evaluation only users

- MiG-23s were obtained from Egypt, and an attempt to incorporate its variable wing design into their Nanchang Q-6. The program did not go ahead and the Q-6 was not built, but some features from the MiG-23 features were incorporated into the J-8II. China currently displays the MiG-23 in several air museums.

- One ex-Syrian MiG-23 flown by a defecting pilot to Israel.[114]

- Samples obtained from Egypt and were mostly stationed in Nellis Air Force Base. The U.S. Air Force operated a small number of MiG-23s, officially designated YF-113, as both test and evaluation aircraft and in an aggressor role for fighter pilot training, from 1977 through 1988 in a program codenamed "Constant Peg".[115]

- Some ex-Iraqi MiG-23s have been used by Flight Test Center (VOC) in the early 1990s.

Civilian operators

- According to the FAA there are 11 privately owned MiG-23s in the U.S.[116]

- Two ex-Czech aircraft, N51734 and N5106E, are registered for civilian use in the United States and are based at New Castle Airport in Wilmington, Delaware.[117]

- An ex-Bulgarian VVS aircraft, N923UB, is operational and on display at the Cold War Air Museum near Dallas, Texas.[118]

Accidents and incidents

- 18 July 1980: three weeks after the loss of Itavia Flight 870, the wreckage of a Libyan MiG-23 and the remains of its pilot were discovered on the Sila Mountains at Castelsilano, southern Italy, around 300 km (190 mi) from Flight 870's crash site.[119]

- 26 April 1984: U.S. Air Force Lieutenant General Robert M. Bond was killed when the MiG-23 he was piloting crashed at the Nevada Test Site.[120] At the time of the mishap, Lt Gen Bond was serving as Vice Commander of Air Force Systems Command at Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland, USA.

- 4 July 1989: a stray Soviet MiG-23M flew 900 km (600 mi) with no-one at the controls, after the pilot had ejected shortly after takeoff, and eventually crashed into a house in Belgium, killing one person.

- 22 December 1992: a Libyan Boeing 727 collided with a Libyan Air Force MiG-23 near Tripoli, causing the death of all 157 people on board the jetliner.

Aircraft on display

Specifications (MiG-23MLD)

Data from Brassey's world aircraft & systems directory, 1996/97[121]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1 sat on a Mikoyan KM-1M ejection seat

- Length: 16.7 m (54 ft 9 in)

- Wingspan: 13.965 m (45 ft 10 in) fully spread

- 7.779 m (25.52 ft) fully-swept

- Height: 4.82 m (15 ft 10 in)

- Wing area: 37.35 m2 (402.0 sq ft) fully-spread

- 34.16 m2 (367.7 sq ft) fully-swept

- Airfoil: root: TsAGI SR-12S (6.5%) ; tip: TsAGI SR-12S (5.5%)[122]

- Gross weight: 14,840 kg (32,717 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 17,800 kg (39,242 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 4,260 l (1,130 US gal; 940 imp gal) internal with provision for up to 3x 800 l (210 US gal; 180 imp gal) drop-tanks

- Powerplant: 1 × Khatchaturov R-35-300[123] afterburning turbojet, 83.6 kN (18,800 lbf) thrust with variable-geometry nozzles dry, 127.49 kN (28,660 lbf) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 2,499 km/h (1,553 mph, 1,349 kn) / M2.35 at altitude

- 1,350 km/h (840 mph; 730 kn) / M1.1 at sea level

- Range: 1,900 km (1,200 mi, 1,000 nmi) clean

- Combat range: 1,500 km (930 mi, 810 nmi) with standard armament, no drop-tanks

- 2,550 km (1,580 mi; 1,380 nmi) with standard armament and 3x 800 l (210 US gal; 180 imp gal) drop-tanks

- Ferry range: 2,820 km (1,750 mi, 1,520 nmi) with 3x 800 l (210 US gal; 180 imp gal) drop-tanks

- Service ceiling: 18,300 m (60,000 ft)

- g limits: +8.5

- Rate of climb: 230 m/s (45,000 ft/min) at sea level

- Take-off distance: 500 m (1,600 ft)

- Landing distance: 750 m (2,460 ft)

Armament

- Guns: 1 × 23 mm Gryazev-Shipunov GSh-23L autocannon with 260 rounds

- Hardpoints: 2 × fuselage, 2 × wing glove and 2 × wing pylons with a capacity of up to 3,000 kg (6,600 lb) of stores,with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets: S-5

- Missiles:

- Bombs: Up to 500 kg (1,100 lb) bombs per hardpoint

According to the MiG-23ML manual, the MiG-23ML has a maximum sustained turn rate of 14.1 deg/sec and a maximum instantaneous turn rate of 16.7 deg/sec. The MiG-23ML accelerates from 600 km/h (373 mph) to 900 km/h (559 mph) in 12 seconds at the altitude of 1000 meters. The MiG-23 accelerates at the altitude of 1 km from 630 km/h (391 mph) to 1300 km/h (808 mph) in 30 seconds and at the altitude of 10–12 km will accelerate from Mach 1 to Mach 2 in 160 seconds.

See also

- 1989 Belgian MiG-23 crash

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Dassault Mirage F1

- Northrop F-5 Tiger II

- General Dynamics F-111

- Shenyang J-8

- Sukhoi Su-24

Related lists

- List of fighter aircraft

- List of Iranian aerial victories during the Iran–Iraq war

- List of Iraqi aerial victories during the Iran–Iraq war

- List of military aircraft of the Soviet Union and the CIS

References

- "Цены". www.airbase.ru.

- Lake 1992, pp. 43–44.

- Mladenov 2004, p. 45.

- Belyakov and Marmain 1992, pp. 351–355.

- Lake 1992, pp. 43–45.

- Lake 1992, p. 45.

- Boyne, Walter J. (2013). Beyond the wild blue a history of the u.s. air force, 1947–2007. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 493. ISBN 1429901802.

- Goebel, Greg. "The Mikoyan MiG-23 & MiG-27 "Flogger" – [1.0] Fighter Floggers". AirVectors.net. v1.0.5 – chapter 1 of 2, 1 Jan 15, greg goebel, public domain. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Davies (2008), ch. 14

- Peck Jr (2012), ch. 4

- Davies (2008), ch. 8

- Mladenov (2016), Ch. 3 - New Design Features

- Mladenov (2016), Ch. 3 - MiG-23 Edition 1971

- Davies (2008), ch. 7

- Davies (2008), ch. 5

- Davies (2008), ch.9

- Davies (2008), ch 10

- Davies (2008), ch.3

- Davies (2008), ch. 10

- Davies (2008), ch. 14

- Davies (2008), ch. 8

- "Family explains Cuban defection." Gainesville Sun, 18 July 1994. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- Peck Jr. (2012), ch. 3

- Davies (2008), ch. 13

- Kondaurov, V. N. "Испытания на Волжских Берегах (Translation: Testing on the Volga shores" (in Russian). testpilot.ru. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- "МиГ-23 в Анголе (Translation: MiG-23 in Angola)" (in Russian). airwar.ru. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- "МиГ-23М (Translation: MiG-23M)" (in Russian). airwar.ru. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- Babich 1999, pp. 24–25

- Ilyin 2000, pp. 36–37

- Hurley, Matthew M. "The BEKAA Valley Air Battle, June 1982: Lessons Mislearned?" Archived 23 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Airpower Journal, Winter 1989. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- "Blooding the MiG-23." Archived 16 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine MiG-23 Flogger, The MiG-23 combat record. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- Walter J. Boyne (2002). Air Warfare: An International Encyclopedia. ABC-Clio. p. 416.

- Pazynich, Sergey. "Агрессоров" (Translation: From the history of Soviet 'Aggression')" (in Russian). airforce.ru. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- "F-16 Air Forces – Pakistan". f-16.net. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Афганистан. Война в воздухе. Виктор Марковский

- "Airframe Details for F-16 #81-0918". f-16.net. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Weintaub, Richard M. "Afghanistan Says It Downed F16 Fighter From Pakistan: U.S. Officials Say Soviet Pilots Involved." Washington Post, 2 May 1987. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- Weisman, Steven R. "Afghans down a Pakistani F-16, saying fighter jet crossed border." The New York Times, 2 May 1987. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- Markovskiy 1997, p. 28

- Sander Peeters. "South Arabia and Yemen, 1945–1995". acig.info. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- "Soviets bolster an Arab ally. Military buildup in South Yemen worries US officials". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Gordon and Dexter 2005, p. 67

- Sander Peeters. "Israeli — Syrian Shadow-Boxing". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "Oryx Blog". spioenkop.blogspot.com.au. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Matthew Weaver (24 July 2012). "Syria crisis: clashes and prison mutiny in Aleppo". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- "Aleppo: BBC journalist on Syria warplanes bombing city". BBC News. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- McElroy, Damien; Samaan, Magdy (24 July 2012). "Syria's regime uses fighter jets for first time as it struggles to contain rebellion". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- "Syria crisis: Rebels 'shoot down warplane'". BBC News. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- "Turkish F-16 shoots down a Syrian MiG-23". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Drones Are Dropping Like Flies From the Sky Over Syria Shoot-downs are becoming commonplace. Tom Cooper. June 22, 2017

- https://web.archive.org/web/20161219172206/http://www.acig.info/CMS/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=37&Itemid=47

- Iran-Iraq War of 1980–1988, Tom Cooper, Farzad Bishop , 2000 – pages-211

- "Chronological Listing of Iranian Air Force Grumman F-14 Tomcat Losses & Ejections." Archived 4 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine ejection-history.org.uk. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- Cooper, Tom. "Iraqi Air-to-Air Victories since 1967." Archived 11 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine ACIG, 25 August 2007. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- David Nicolle; Tom Cooper (2004). Arab MiG-19 and MiG-21 Units in Combat. Osprey Publishing. p. 82.

- "Iraqi Air-to-Air Victories since 1967". ACIG. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Cooper and Bishop 2003, p. 46.

- Cooper and Bishop 2004, pp. 85–88.

- Cooper and Bishop 2003, pp. 87–88.

- "Потери ВВС Ирака". airwar.ru. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Sander Peeters. "Iraqi Air-to-Air Victories since 1967". ACIG. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Sander Peeters. "Iranian Air-to-Air Victories 1976–1981". ACIG. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Sander Peeters. "Iranian Air-to-Air Victories, 1982-Today". ACIG. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "iranian_F_4_Phantom_LOSSES". ejection-history.org.uk. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Tehnika i vooruzhenie", August 2000. pp.4

- Cooper and Bishop 2004, pp. 27–34.

- Sander Peeters. "Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait; 1990 - www.acig.org". acig.info. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- "Iraqi Perspectives Project Phase II. Um Al-Ma'arik (The Mother of All Battles): Operational and Strategic Insights from an Iraqi Perspective" (PDF). p. 353. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- "Coalition Air-to-Air Victories in Desert Storm". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "USAF Manned Aircraft Combat Losses 1990–2002" (PDF).

- "RAF – RAF Tornado Aircraft Losses". mod.uk. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- "Aerei Militari – Tornado IDS". aereimilitari.org. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- "F-16 Aircraft Database: F-16 Airframe Details for 86-0262." F-16.net. Retrieved: 16 May 2008.

- "Cuban Air-to-Air Victories". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Cooper, Tom. "Angola: Claims & Reality about SAAF Losses." Central, Eastern & Southern Africa Database, 2 September 2003. Retrieved: 19 October 2011.

- Heitman, Helmoed-Romer. War in Angola: The Final South African Phase. Lauderhill, Florida: Ashanti Publishing, 1990. ISBN 978-0-620-14370-7.

- Cooper, Tom. "Libya & Egypt, 1971–1979." Western & Northern Africa Database, 13 November 2003. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- Cooper, Tom (28 December 2017). "The Final Flight of Ezzedin Khalil". warisboring.com. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- "Italians conclude crashed plane was shot down in 1980".

- "Libyan MIG-23 Shot Down Over Chad, Army Says". Los Angeles Times. 6 January 1987.

- Greenhouse, Steven (9 September 1987). "Big Libyan Losses Claimed By Chad". The New York Times.

- Aneja, Atul. "Air strikes deter advance on Tripoli." The Hindu News, 1 March 2011.

- Karam, Souhail et al. "Libyan website reports rebels sink Gaddafi ships." reuters.com, 15 March 2011. Retrieved: 20 March 2011.

- Pannell, Ian. "Fighter jet 'shot down' over Benghazi." BBC, 19 March 2011.

- "Benghazi 'bombarded by pro-Gaddafi forces'." BBC News, 20 March 2011.

- "Update 1-French forces destroy seven Libyan aircraft on ground." Reuters, 26 March 2011.

- Leyne, Jon. "Libya: Fierce battle for second day in Ajdabiya." BBC, 10 April 2011. Retrieved: 12 April 2011.

- "Retired general launches war against Islamists in eastern Libya". Janes. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Libya Dawn aircraft crashes during raid on Zintan". janes.com. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Ranter, Harro. "Accident Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-23ML 6472, 04 Jan 2016". aviation-safety.net.

- Ranter, Harro. "Accident Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-23ML 6132, 08 Feb 2016". aviation-safety.net.

- "Another Libyan Air Force plane shot down or crashed in Benghazi". 12 February 2016.

- Martin, Guy. "Last flyable Libyan Air Force MiG-23 shot down – defenceWeb". www.defenceweb.co.za.

- Arnaud, Delalande (28 February 2016). "AeroHisto – Aviation History: Libyan National Army Air Force MiG-23ML serial #26453 entered in service".

- TeamAirsoc. "LIBYAN AIR FORCE LOST ITS LAST MIG-23 - airsoc.com".

- Arnaud, Delalande (29 March 2016). "AeroHisto – Aviation History: "Libyan airstrikes" situation update 26–28 March 2016".

- Arnaud, Delalande (5 May 2016). "AeroHisto – Aviation History: Libyan National Army Air Force has now two MiG-23BNs operational".

- Arnaud, Delalande (13 May 2016). "AeroHisto – Aviation History: "Libyan airstrikes" situation update 7 – 13 May 2016".

- https://www.africanmilitaryblog.com/2019/08/libya-frankenstein-mig-23-flogger-fighter-jet-take-flight

- https://www.itamilradar.com/2019/12/07/lna-mig-23-shot-down-in-tripoli/

- https://theaviationist.com/2019/12/08/libyan-national-army-air-force-mig-23ml-shot-down-by-manpads-near-tripoli/

- "Info" (PDF). www.hrw.org.

- "Eritrea's Chief Sees No Halt in Border War With Ethiopia". The New York Times. 7 June 1998.

- "Ethiopia hits Asmara airport". BBC News. 29 May 2000.

- Sander Peeters. "II Ethiopian Eritrean War, 1998–2000". ACIG. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- John Pike. "1999 Kargil Conflict". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- https://www.defencetalk.com/mig-23-flogger-16805/

- "Libya- LAF photos of MiG-23 that was fully restored after 20 years being out of service, now flying from Benghazi - Today news from war on Daesh, ISIS in English from Somalia, Egypt, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria - isis.liveuamap.com". Today news from war on Daesh, ISIS in English from Somalia, Egypt, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria - isis.liveuamap.com.

- Oryx (26 September 2016). "Oryx Blog: Back from retirement, Sudan's MiG-23s take to the skies".

- "Portfolio: Algerian Air Force thru History". Retrieved 14 November 2014.