Metamynodon

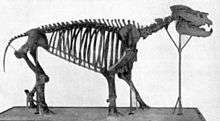

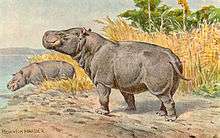

Metamynodon is an extinct genus of amynodont rhino that lived in North America (White River Fauna) and Asia from the late Eocene until early Oligocene[1], although the questionable inclusion of M. mckinneyi could extend their range to the Middle Eocene.[2] The various species were large, displaying a suit of semiaquatic adaptations similar to those of the modern hippopotamus despite their closer affinities with rhinoceroses.

| Metamynodon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | †Amynodontidae |

| Genus: | †Metamynodon Scott & Osborn, 1887 |

| Species | |

| |

Taxonomy

Metamynodon is a member of the extinct family Amynodontidae, sometimes called "swamp rhinos" as they were once all believed to be semi-aquatic. It is split into two tribes: the semi-aquatic Metamynodontini–Paramynodon, Sellamynodon, Megalamynodon, and Metamynodon–and the tapir-like Cadurcodontini–Procadurcodon, Zaisanamynodon, Cadurcodon, and Cadurcotherium. The Metamynodontini are found across the world, with Paramynodon from Myanmar, Sellamynodon from Romania, and Megalamynodon and Metamynodon from North America.[3] Megalamynodon is likely the ancestor of Metamynodon, though it is possible it could have evolved from an Asiatic ancestor.[4]

Metamynodon was first described in 1887 by William Berryman Scott and Henry Fairfield Osborn based on a skull of M. planifrons found in the White River Formation.[5]

In 1922, paleontologist Clive Forster-Cooper initially described tooth remains from Balochistan, Pakistan as M. bugtienses before returning 2 years later and reassigning it to the genus Paraceratherium.[6][3]

Metamynodon bones are common in Early Oligocene riverbed deposits of Badlands National Park in South Dakota, giving them the nickname "the Metamynodon channels."[7][4]

In 1981, a large jawbone, 41723-5, from Brewster County, Texas was described as M. mckinneyi, named after one of the discoverers Billy Pat McKinney, and was found in an area dated to 43 mya in the Late Eocene. The jawbone and tusks were more massive than that of M. chadronensis, and it could represent either a transitional phase between Amynodon and M. chadronensis, or simply a migrant to the area.[8]

Description

Metamynodon planifrons, the largest species, was about 4 metres (13 ft) in length and 1.8 metric tons (2 short tons) in weight, and, although it was distantly related to modern rhinos, looked more like a hippo (Hippopotamus amphibius).[9] Its front legs had four toes instead of the three found in modern rhinos.[10]

Like other swamp rhinos, Metamynodon has large canines, and Metamynodonts generally have larger canines than other swamp rhinos. The shortened snout and large nostrils indicate Metamynodon had a prehensile lip. Metamynodonts were more brachycephalic and had a broader than longer snout. The nostrils would have been on the top portion of the snout like the modern hippo. As other aquatic mammals, Metamynodon had a poorer sense of smell than other swamp rhinos. The eyes were located high on the skull so it could see while also being completely submerged.[10][4] It had a dental formula of 3.1.3.33.1.2.3.[5]

Like other aquatic mammals, Metamynodon had small neural spines projecting upwards from the thoracic vertebrae, indicating weak neck muscles, which probably was due to buoyancy and a lack of necessity to support the head while submerged. The ribcage was broad and Metamynodon had a barrel-like chest similar to the hippo, which could either be an adaptation to an expanding digestive tract or to develop muscles necessary to prevent rolling over in the water. Like other aquatic mammals, the leg muscles–popliteus in the knee; gastrocnemius, soleus, and peroneus tertius in the calf; and extensor digitorum longus in the foot–were all large and well-developed, probably to exert more force while walking and to better wade through muddy soil.[4]

Paleobiology

_(19730529624).jpg)

Like other Metamynodonts, Metamynodon was semi-aquatic. Like the modern hippo, Metamynodon was likely a grazer, feeding on grass and tough plant material at night and residing in the water during the day. Like hippos, males may have used their large tusks for fighting or for finding food in river banks. They went extinct in the Late Oligocene.[10][7]

The Early Oligocene Badlands National Park were probably streams coursing through grasslands, gallery woodlands, and savannas. Metamynodon was probably abundant and restricted to the streams; common in the gallery woodlands were the horse Mesohippus and the pig-like Merycoidodon; and in the savannas the rabbit Palaeolagus, the deer-like Leptomeryx and Hypertragulus.[11] During the Whitneyan stage of the NALMA classification, still in the Early Oligocene, Metamynodon becomes more rare.[4]

The Early Oligocene Badlands National Park had several carnivores: the dog-like Hyaenodon, the dog Hesperocyon, the bear dog Daphoenus, the false saber-toothed cat Dinictis, and the weasel-like Paleogale. It also had a wide array of other animals including: the entelodont pigs Daeodon and Archaeotherium; the deer Leptomeryx and Protoceras; the rodents Ischyromys, Eumys, and Megalagus; the lizard Peltosaurus; and the small marsupial Herpetotherium. A turtle, Oligogopherous, has also been found, along with isolated fish fossils.[12]

See also

References

- "Metamynodon". Fossilworks.

- Wall, William P. (1989). "The phylogenetic history and adaptive radiation of the Amynodontidae". In Prothero, Donald R; Schoch, Robert M. (eds.). The Evolution of perissodactyls. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195060393.

- Tissier, J.; Becker, D.; Codrea, V.; Couster, L.; Fărcaş, C. (2018). "New data on Amynodontidae (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from Eastern Europe: Phylogenetic and palaeobiogeographic implications around the Eocene-Oligocene transition". PLOS ONE. 13 (4): e0193774. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0193774. PMC 5905962. PMID 29668673.

- Wall, W. P.; Heinbaugh, K. L. (1999). "Locomotor adaptations in Metamynodon planifrons compared to other amynodontids (Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotoidea)" (PDF). National Parks Paleontological Research. 4: 8–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-19. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- Scott, W. B.; Osborn, H. F. (1887). Preliminary Account of the Fossil Mammals from the White River Formation contained in the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 165–169. ISBN 978-1-248-54867-7.

- Forster-Cooper, C. (1922). "LXXIV.—Metamynodon bugtiensis, sp. n., from the Dera Bugti deposits of Baluchistan.—Preliminary notice". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 9 (53): 617–620. doi:10.1080/00222932208632717.

- Prothero, D. R.; Schoch, R. M. (2002). Horns, Tusks, and Flippers: The Evolution of Hoofed Mammals. JHU Press. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-8018-7135-1.

- Wilson, J. A.; Schiebout, J. A. (1984). Early Tertiary Vertebrate Faunas Trans-Pecos Texas: Amynodontidae (PDF). Pearce-Sellards Series. University of Texas. pp. 48–52.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-20. Retrieved 2012-05-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-84028-152-1.

- Wall, W. P.; Collins, C. M. (1998). "A comparison of feeding adaptations in two primitive ruminants, Hypertragulus and Leptomeryx, from the Oligocene deposits of Badlands National Park" (PDF). National Park Service Paleontological Research: 13–17.

- Benton, R. C.; Terry, Jr., D. O.; Cherry, M.; Evanoff, E.; Grandstaff, D. E. (2014). Paleontologic Resource Management at Badlands National Park, South Dakota: A Field Guide for the 10th Conference on Fossil Resources (PDF). National Park Service.