Merck's rhinoceros

Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis, commonly known as Merck's rhinoceros, is an extinct species of rhino known from the Middle to Late Pleistocene of Eurasia. One of the last members of the genus Stephanorhinus, it is considered to be a typical component of the interglacial Palaeoloxodon large faunal assemblage in Europe.[1] It is most closely related to the Woolly rhinoceros and the Sumatran rhinoceros. In Europe it was sympatric with the narrow nosed rhinoceros S. hemitoechus. It is noted for its very large size, among the largest of Pleistocene rhinoceroses, approaching that of Elasmotherium.

| Merck's rhinoceros | |

|---|---|

| Skull from Azerbaijan | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae |

| Genus: | †Stephanorhinus |

| Species: | †S. kirchbergensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis Jäger, 1839 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Etymology and taxonomy

The first part of the genus name is derived from that of King Stephen I of Hungary, and the second part from 'rhinos' (ρινος, meaning "nose"), as with Dicerorhinus. The species name was given by Georg Friedrich von Jäger in 1839 for Kirchberg an der Jagst in Baden-Württemberg, where the type specimens had been found.[2] It is often known in English (and equivalents in other languages) as Merck's rhinoceros after Carl Heinrich Merck, who gave the initial name to the species in 1784 as Rhinoceros incisivus, that is now considered a nomen oblitum, and who after a widely used junior synonym of the species, Rhinoceros/Dicerorhinus mercki (historically several alternate spellings) was named by Johann Jakob Kaup in 1841.[3]

Origin

The origin of the species is obscure, with various authors suggesting either a European or Asian origin. The earliest definitive records are from Choukoutien Locality 13, in Fangshan District near Beijing at around the Early-Middle Pleistocene transition,[4] though the older records of Stephanorhinus lantianensis and Stephanorhinus yunchuchenensis have been suggested to be synonyms of S. kirchbergensis by some sources.[5] It appears in Europe during the early Middle Pleistocene between 0.7-0.6 Ma, existing alongside the already present S. hundsheimensis.[6] A complete mitochondrial genome obtained from a permafrost specimen[7] and proteome studies[8] suggest that it is more closely related to the Woolly rhinoceros than the Sumatran rhinoceros, but its relationship to other Stephanorhinus species remains unclear.

Range

Its range spans from Europe to East Asia, but appears to be absent from the Iberian Peninsula.[9][10] Its range extended into the Arctic Circle, with a 70–48 thousand-year-old skull known from arctic Yakutia in the Chondon River valley[7] and a late Middle Pleistocene aged lower jaw from the Yana River valley.[11] Teeth are known from caves in Primorsky Krai , suggested to date between 50,000 and 25,000 years ago based on dates of other bones found in the deposit, which are the easternmost known records.[12] A tooth of S. cf. kirchbergensis of an unknown age is known from the Lut Desert in eastern Iran.[13] It is fairly common throughout the Pleistocene in North China,[5] but is a rarer component of South Chinese assemblages,[14] being known from around 30 localities in the region.[4] Antoine (2012) states that D. choukoutienensis, D. lantianensis, and D. yunchuchenensis are local names for the taxon, without elaboration.[5] Its range was strongly controlled by glacial cycles, with the species experiencing repeated cycles of expansion and contraction as the ice sheets advanced, this accounts for its relative rarity of its remains in comparison to the woolly rhinoceros.[9] The species' range underwent significant reduction during the Last Glacial Period, with the youngest records from Italy being in MIS 4 and 3.[15] The youngest reliable records in China are from the Rhino Cave in Hubei, which is early Late Pleistocene in age.[14] Though less definitive remains are known from near Harbin in Heilongjiang, which are thought to be 20 kya in age.[4] Records from Migong Cave just south of the Yangtze River in the Three Gorges area are suggested to date to MIS 2.[16] It is presumed to have had a preference for closed forest and woodland habitats, as opposed the to open grassland habitats favoured by S. hemitoechus.[1]

Diet

Merck's rhinoceros appears to have been a mixed feeder with a more specialised diet than S. hundsheimensis and the grazing diet hypothesised for S. hemitoechus. Despite their morphological differences, its preferences were not significantly different than S. hemitoechus, suggesting dietary convergence due to low habitat variability during the Pleistocene.[6] Analysis of plant material embedded within teeth from the Neumark-Nord locality in Germany found remains of Populus, Quercus, Crataegus, Pyracantha, Urtica and Nymphaea as well as indeterminate remains of Betulaceae, Rosaceae, and Poaceae.[17] Preserved plant remains found with the teeth on the arctic Chonon skull included twigs of willow, birch and abundant larch alongside fragments of heather; sedges were notably absent.[7]

Gallery

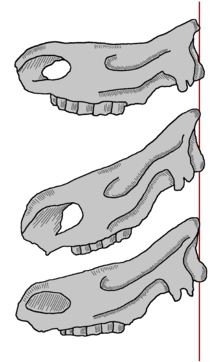

Partial skull in Stuttgart

Partial skull in Stuttgart- 300,000 year old dentary fragment from the United Kingdom in the NHM, London

Remains of Merck's rhinoceros from Germany

Remains of Merck's rhinoceros from Germany View of the top of the snout of a S. kirchbergensis skull, showing the rugose texture of the horn attachment area

View of the top of the snout of a S. kirchbergensis skull, showing the rugose texture of the horn attachment area

References

- Pushkina, Diana (July 2007). "The Pleistocene easternmost distribution in Eurasia of the species associated with the Eemian Palaeoloxodon antiquus assemblage". Mammal Review. 37 (3): 224–245. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2007.00109.x. ISSN 0305-1838.

- Georg Friedrich Jäger: Über die fossilen Säugetiere welche in Württemberg in verschiedenen Formationen aufgefunden worden sind, nebst geognostischen Bemerkungen über diese Formationen. C. Erhard Verlag, Stuttgart, 1835–39

- Johann Jakob Kaup: Akten der Urwelt oder Osteologie der urweltlichen Säugethiere und Amphibien. Darmstadt, Verlag des Herausgebers, 1841

- Tong, Hao-wen (November 2012). "Evolution of the non-Coelodonta dicerorhine lineage in China". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (8): 555–562. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2012.06.002.

- Antoine, Pierre-Olivier (March 2012). "Pleistocene and Holocene rhinocerotids (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Indochinese Peninsula". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (2–3): 159–168. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2011.03.002.

- van Asperen, Eline N.; Kahlke, Ralf-Dietrich (January 2015). "Dietary variation and overlap in Central and Northwest European Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis and S. hemitoechus (Rhinocerotidae, Mammalia) influenced by habitat diversity" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 107: 47–61. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.10.001.

- Kirillova, Irina V.; Chernova, Olga F.; van der Made, Jan; Kukarskih, Vladimir V.; Shapiro, Beth; van der Plicht, Johannes; Shidlovskiy, Fedor K.; Heintzman, Peter D.; van Kolfschoten, Thijs; Zanina, Oksana G. (November 2017). "Discovery of the skull of Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis (Jäger, 1839) above the Arctic Circle". Quaternary Research. 88 (3): 537–550. Bibcode:2017QuRes..88..537K. doi:10.1017/qua.2017.53. ISSN 0033-5894.

- Cappellini, Enrico; Welker, Frido; Pandolfi, Luca; Ramos-Madrigal, Jazmín; Samodova, Diana; Rüther, Patrick L.; Fotakis, Anna K.; Lyon, David; Moreno-Mayar, J. Víctor; Bukhsianidze, Maia; et al. (October 2019). "Early Pleistocene enamel proteome from Dmanisi resolves Stephanorhinus phylogeny". Nature. 574 (7776): 103–107. Bibcode:2019Natur.574..103C. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1555-y. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 6894936. PMID 31511700.

- Billa, E.M.E. 2011a. Occurrences of Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis (Jäger, 1839) (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae) in Eurasia - An account. Acta Palaeontologica Romaniae 7: 17-40

- Billia, E.M.E., Zervanová, J., 2015. New Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis(Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae) records in Eurasia. Addenda to a previous work. Gortania.Geologia, Paleontologia, Paletnologia36, 55–68.

- Shpansky, A. V.; Boeskorov, G. G. (July 2018). "Northernmost Record of the Merck's Rhinoceros Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis (Jäger) and Taxonomic Status of Coelodonta jacuticus Russanov (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae)". Paleontological Journal. 52 (4): 445–462. doi:10.1134/S003103011804010X. ISSN 0031-0301.

- Kosintsev, P. A.; Zykov, S. V.; Tiunov, M. P.; Shpansky, A. V.; Gasilin, V. V.; Gimranov, D. O.; Devjashin, M. M. (March 2020). "The First Find of Merck's Rhinoceros (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae, Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis Jäger, 1839) Remains in the Russian Far East". Doklady Biological Sciences. 491 (1): 47–49. doi:10.1134/S0012496620010032. ISSN 0012-4966.

- Hashemi, N; Ashouri, A; Aliabadian, M; M. Gharaie, M; Sánchez Marco, A; Louys, J (2016). "First report of Quaternary mammals from the Qalehjough area, Lut Desert, Eastern Iran". Palaeontologia Electronica. doi:10.26879/539. ISSN 1094-8074.

- Tong, HaoWen; Wu, XianZhu (April 2010). "Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis (Rhinocerotidae, Mammalia) from the Rhino Cave in Shennongjia, Hubei". Chinese Science Bulletin. 55 (12): 1157–1168. Bibcode:2010ChSBu..55.1157T. doi:10.1007/s11434-010-0050-5. ISSN 1001-6538.

- Lacombat, Frédéric (2006). "Pleistocene Rhinoceroses in Mediterranean Europe and in Massif Central (France)". CFS Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg.

- Pang, Libo; Chen, Shaokun; Huang, Wanbo; Wu, Yan; Wei, Guangbiao (April 2017). "Paleoenvironmental and chronological analysis of the mammalian fauna from Migong Cave in the Three Gorges Area, China". Quaternary International. 434: 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.11.039.

- Jan van der Made und René Grube: The rhinoceroses from Neumark-Nord and their nutrition. In: Harald Meller (Hrsg.): Elefantenreich – Eine Fossilwelt in Europa. Halle/Saale 2010, S. 382–394