McVickar House

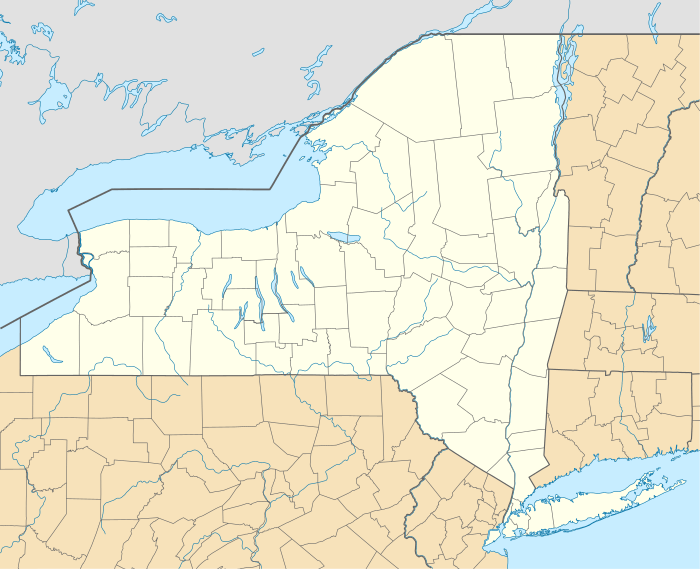

The McVickar House is located at 131 Main Street in Irvington, New York, United States. It is a wooden frame house built in the middle of the 19th century in the Greek Revival architectural style with some Picturesque decorative touches added later. In 2004 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[2]

McVickar House | |

South elevation and east profile, 2009 | |

| |

| Location | Irvington, NY |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | White Plains |

| Coordinates | 41°2′20″N 73°51′55″W |

| Built | 1853[1] |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 03001398 |

| Added to NRHP | January 14, 2004[2] |

It was built by John McVickar, an Episcopalian minister who moved to the area to be close to his friend Washington Irving and establish a school, which later became the nearby Church of St. Barnabas. His son, the church's first pastor, lived in the house. It is the second oldest house on the village's Main Street.[1]

Eventually it became the property of Consolidated Edison, the regional electric utility, which still runs a small facility in the backyard. It was rented out until the 1990s. Today, after extensive restoration, it is home to the Irvington Historical Society. It operates the house both as its offices and a museum whose exhibits include a section of the first transatlantic telegraph cable.

Building

The house is located on the north side of Main Street between North Broadway (U.S. Route 9) and Dearman Street. Surrounding buildings are generally commercial buildings of a similar scale from the 20th century. To the north is the Church of St. Barnabas, also listed on the Register. Further down Main Street, which slopes west toward the Hudson River, are two other properties listed on the Register. The trailway over the Old Croton Aqueduct, a National Historic Landmark, intersects Main two blocks to the west. On the next block, at the corner of Main and North Ferris Street, is Irvington Town Hall, still the village's municipal building. Main and portions of its adjoining streets have been proposed for a future historic district.[1]

The lot on which the house stands is 59 by 100 feet (18 by 30 m) in size. At its rear is an electrical substation that is not included in the Register listing. A small garden, set off from the sidewalk by a metal railing, is located at the street, next to the front steps on the west side.[1]

The house itself is a two-and-a-half-story three-by-two-bay wood frame structure on a raised fieldstone foundation, allowing for an English basement at the front. It is sided in the original clapboard and topped with a side-gabled metal roof. A single brick chimney pierces it at the east end.[1]

Wooden steps with decorative wooden railings of solid wood panels pierced by saw-cut quatrefoils climb to the hip-roofed porch which runs the length of the first story on the south (front) facade. Immediately east of them another set of steps leads down to the English basement, currently occupied by a small clothing store. The porch roof is supported by square pillars with knee braces at the top and a molded cornice. At the deck, a baluster similar to those on the steps up to the porch connects the pillars.[1]

All windows are six-over-six double-hung sash. Those on the front are flanked by louvered shutters. On the northwest corner is an enclosed smaller porch supported by square columns with simple pedestals and capitals. The overhanging eaves of the rooflines are decorated with saw-cut vergeboards.[1]

A paneled wooden door inside an entry with architrave, transom and sidelights in the westernmost bay leads to an entrance hall. The interior has been remodeled but retains some original features, most notably the staircase in that entrance hall. It has a turned mahogany newel post, round railing, and turned balusters.[1]

In the front parlor the fireplace has its original wooden mantelpiece and chimney breast. The rear has been reconfigured, with some doors and walls removed. Upstairs is another original newel post, and some of the original lath and plaster on the walls. The basement has also been modified, but may have contained the original kitchen and dining room.[1]

History

After a lengthy career in the Episcopal Church as a military chaplain and two-time acting president of Columbia University, where he taught the first course on political economy (the discipline now known as economics) in the U.S., The Rev. John McVickar retired to what was then known as Dearman in 1852 and built the house. His goal was to establish a chapel school he had long envisioned, with help from his friends Washington Irving, who lived at the nearby Sunnyside estate, and John Jay. It was established on a 30-acre (12 ha) parcel just north of where the house is now.[1]

McVickar persuaded his son William to come to Dearman to preside over the school. It did not last long, eventually moving north up the Hudson Valley and becoming the root of what is today Bard College. McVickar stayed as the rector of what was now the Church of St. Barnabas. He lived in the Greek Revival house his father had built until the current rectory at St. Barnabas was built.[1]

At some point around William McVickar's death in 1868 the Picturesque detail was added to the original design. This was in keeping with trends of the time, particularly in the Hudson Valley, where the influence of Andrew Jackson Downing remained strong even after his death around the time John McVickar had taken up residence. As a result of the combination of Greek Revival form and plan with the Picturesque decoration, the house has a unique and distinct Victorian quality to it.[1]

William McVickar's daughters inherited the house from him. They sold it to their brother John a few months later, and he in turn sold it to a local grocer in 1870. It passed through a few other owners until 1957, when Consolidated Edison, the electric utility that serves Westchester County as well as New York City, bought the house in order to build the substation in the rear. They subdivided the house's interior and rented it out to various tenants through 1992.[1]

After that time the house grew neglected. It had had asbestos composite shingles placed over its clapboard siding and asphalt shingles on its roof. In the early 2000s its historic potential was recognized and it was restored in order to serve as home to the Irvington Historical Society.[1] Con Ed sold the house to the village. The work cost a half million dollars, and included a new roof, siding, windows, heating and plumbing.[3]

The Society moved in in 2005 when the work was done. The basement became a children's center and the first story the main exhibit hall. Upstairs the rooms are used for office space, storage and work.[4]

Among the items in the permanent collection are a section of the first transatlantic telegraph cable, donated by the family of its builder, Cyrus West Field, who died in Irvington.[4] Past exhibits have been devoted to household chores[5] and collectibles.[6] The museum is open two afternoons a week.[7]

References

- Shaver, Peter (February 6, 2003). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, McVickar House". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on September 5, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- Campbell, Francis D.; Ryan, Pat (Fall 2009). "Pete Oley – A Retrospective". The Roost. 10 (2): 5.

- Steiner, Henry (July 28, 2006). "Tradition and Passion — Irvington's Peter Oley". River Journal. Tarrytown, NY. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- "Choring Around the House". Irvington Historical Society. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- Jones, Colleen Michele (March 18, 2011). "'Things, Etc.,' the sequel, a potluck of local passions". The Rivertowns Enterprise. Dobbs Ferry, NY. Archived from the original on May 1, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- "The Irvington Historical Society". Irvington Historical Society. November 10, 2011. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to McVickar House. |

- McVickar House, at Irvington Historical Society