Manjampatti Valley

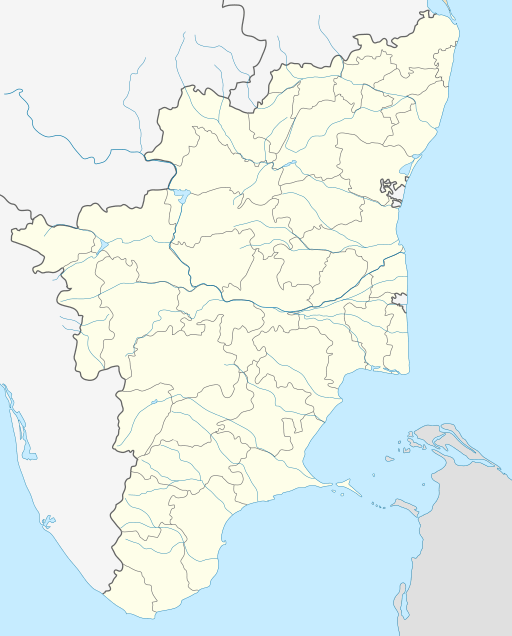

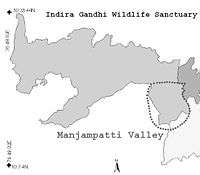

Manjampatti Valley is a 110.9 km2 (42.8 sq mi) protected area in the eastern end of Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary and National Park (IGWS&NP) in Tirupur District, Tamil Nadu, South India. It is a pristine drainage basin of shola and montane rain forest with high biodiversity recently threatened by illegal land clearing and cultivation.[1][2]

| Manjampatti Valley | |

|---|---|

| Core zone of Indira Gandhi National Park | |

Talinji Village & Vellari Malai Peak | |

Manjampatti Valley | |

| Floor elevation | 2,219 m (7,280 ft) |

| Area | 110.905 square kilometres (42.821 sq mi) |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 10°18′45″N 77°15′2″E |

National Park

Manjampatti Valley is the eastern core zone of the Indira Gandhi National Park (IGWS&NP)[3] It is managed as an Ib-Wilderness Area:

a large area of unmodified or slightly modified land, retaining its natural character and influence, without permanent or significant habitation, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural condition.[4]

The Tamil Nadu Forest Department has divided the valley into 3 administrative areas: Thalinji beat 4290 ha, Manjampatti beat 3741.75 ha and Keelanavayal beat 3058.75 ha. Total = 11,090.5 ha = 110.905 km2 (42.821 sq mi)

To the east it adjoins the western ends of the Kodaikanal and Dindigul Forest Districts. These Forests will make up part of the new Kodaikanal Wildlife Sanctuary and the proposed Palani Hills National Park. To the south and west it adjoins Munnar forest Division and Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary in Idukki District, Kerala. To the north it adjoins the north slope of the Amaravathy River basin in the 172.5050 km2 (66.6046 sq mi) Amaravathy Range of IGWS&NP.[1] p. 2.

Some areas of the drainage basin are not included within the political boundaries of the national park, including the Kodaikanal Taluk villages of Kumbur, Mannavanur and Kilanavayal; Upper Palani Reserve Forest (Kilanavayal) and a 2 km wide strip of the east end of Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary.[1] p. 180,[5]

The IGWS&NP and the Kodaikanal and Dindigul Forest Districts are designated the Anaimalai Conservation Area,[6] a two-year collaborative project of the Wildlife Institute of India and the U.S.D.A. Forest Service.[7] Manjampatti Valley is under the protection of the Coimbatore Forest Office; Wildlife Warden-Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary[8] A license is required for entry.

History

Manjampatti derived its name from two Tamil words, manjal meaning yellow and patti meaning "cattle fold" or small village; there is a local opinion that it was so named because of endemic wild mango trees here.

Iron Age (1200-200 BC) Dolmens, consisting of a stone floor slab 3 to 5 feet long, 3 stone walls about 2 feet high, and a “roof” stone slab, found on at least 2 stony hilltops on the edges of the valley.. and..the existence of unexpectedly large temple ruins in the isolated village of Thalinji, and the later (1559 - 1736) assignment of land by Madurai Nayak Dynasty kings to cultivators in the upper Palanis, indicate that there has been continuous interaction from prehistoric times to the present between plains people and the ethnic groups in these hills. Some groups relying on hunting and gathering partially retained their pre-civilizational lifestyle up to the last century. [9]

The earliest known residents of the area are the Palaiyar (meaning "old ones", incorrectly translated as Paliyan), a Tamil-speaking tribal people, who have been seen in the past 35 years living in small caves in the valley. Historically close extended Palaiyar family groups foraged and hunted at least 128 forest species for subsistence. In the past century they increasingly depended on shifting cultivation and collection and trading of non timber forest products of over 60 species for: food (14), incense & toiletries (11) medicines (13), construction materials & precious woods (9) and miscellaneous (13) honey, tubers, fruits, herbs, flowers, bark, seeds, fibers, gum, leaves, logs and oils.

Since establishment of the IGWS&NP in 1976, Palaiyar trading was gradually but severely restricted. They are now allowed to collect only tamarind from one small area outside Manjampatti Valley. Their strong cultural ties to the area and traditional avoidance of outsiders keeps them attached to their forest habitat. They must now depend on intermittent plantation labor, primitive low yield cultivation in restricted areas, liaisons with forest product smugglers and poachers, government programs and charity.[10]

Communities

In 2002 there were 401 tribal persons living in three settlements within IGWS&NP boundaries in the valley. This is an average population density of 3.65 persons/km2, 40% higher than the 2.6 persons/km2 living in all 36 tribal settlements in the entire 1769 km2 IGWS&NP.[11] Their peaceful ancient culture in this area is increasingly fragmented as they assimilate modern Tamil customs and values.,.[12][13] The villages have no link roads, no electricity (some solar lamps have been installed recently), no running water, no government school, no medical facilities and no shops.[14]

In addition there are three villages within the valley watershed but outside the National Park boundaries: Mannavanur pop. 5,927,[15] Kumbur pop. 500,[16] and Kilanavayal 124 families.[17]

Thalinji

Thalinji village at 533 metres (1,749 ft), near the bottom of the valley above the banks of the Ten Ar River, has about 150 houses (pop: m-168, f-155). Most of the people are Pulaiyar caste, early cultivators, but there are some Malaimarasar tribal people, who do agriculture and coolie work.

This place had some importance in medieval times, as there are mounds with 15th century ruins of a Vijayanagar Dynasty [1] p. 267 Kondaiaman temple [5] with a substantial temple tank, and numerous scattered stone carvings and broken statues of goddesses such as Kondaiamman and Mariamman and gods Ganesha, and Krishna, with some text inscriptions. The villagers say they know no history of the temple.

The village is a ward under the Manupatti Panchayat near the Amaraavathi dam, but the people have decided to not elect a representative. They do rely on the Forest Department for many kinds of assistance and advice. When the British created the Amaravathi Reserved Forest they allocated 200 acres (81 ha) to the village for cultivation. This was divided up among families by stone boundary markers, which still exist, but land titles were not given.

Thalinji people cultivate rice (monsoon crop) and butter beans and no other vegetables or crops. They keep a few cows, buffaloes, goats, and chickens. They are allowed to collect minor forest products for their own use, but not to sell. There is a one-room Anti-Poaching Camp used intermittently by forestry staff on their rounds. There is a school with a teacher posted, and a doctor is supposed to come every week but actually comes less than once a month. Men sometimes go out to work in sugarcane fields on the plains, and women go to work in the Manjampatti fields. Thalinji has no store or tea shop. The people do not integrate well in the modern society and economy, though they have accepted Photovoltaic powered home lighting devices from the District collector.

Manjampatti

Manjampatti village at 730 metres (2,400 ft), near the middle of the valley has 59 households with 191 persons (95 males and 96 females) [18] dispersed among its many agricultural fields located inside a bend of the Ten Ar just below its junction with the Kumbar and Manalaar streams.

It is ethnically more diverse than Talinji. Pulaiyar were the majority inhabitants of Manjampatti when the British gave land to the village for cultivation. About 15 families of Muthuvar, another "tribal" group, live in Manjampatti village where they do cultivation and labor work. Some Theivar people, a widespread plains agricultural jaathi (caste), came to live in Manjampatti long ago and engage in agriculture on the village lands. There are also a few houses of other plains jaathis such as Chakkliyar (originally leather-workers). Because of these jaathis, Manjampatti village has some features of plains Tamil villages such as eating of newer types of vegetables and having tea shops.

Manjampatti comes under the Mannavanur Panchayat and sends its Ward Member up to the monthly meetings. The people receive no benefit from the Panchayat, and prefer to rely on the Forest Department. Manjampatti falls under Kodaikanal Taluk office, and the people must travel far to Kodaikanal for official services such as getting a ration card. The ration items (rice, sugar, kerosene) are sent to an agent on the Amaravaathi-Munnar Road (SH 17) where the people go to collect them. The village has a small part-time general store selling cooking items and two part-time tea shops. There is a basic primary school of a type designed for tribal people, which is able to provide Transfer Certificates (TC) to students.

There is a Forest Department Anti-Poaching Camp with four full-time staff. There is a polling station at the Hydro Matric Survey Building in Manjampatti for all voters from Manjampatti, Muthuvankudi and Mungilpallam (Mannavanur (r.v) Ward-5).[19]

The village has a Moopan (headman), assisted by a group of elder men, who organizes activities such as maintaining irrigation channels and resolving disputes, but this position is not recognized in the Panchayat system. The Moopan can be of any caste, and serves as long as he has the confidence of the people. If someone commits a serious crime, the Moopan will turn the suspect over to the Forest Department, which will arrange for him to be detained by police on the plains.

Manjampatti was given land for cultivation when the Reserved Forest was created and the families have kept their respective fields marked with the original stone boundaries. Villagers earlier practiced shifting cultivation, growing millets such as raagi, thinai and kambu. Later the Forest Department forbade shifting cultivation and restricted cultivation to the allotted lands. The crops now are rice in rainy season and butter beans otherwise, though with a more diverse population a few vegetables such as eggplant and tomatoes are grown. Farmers here have to protect their crops from wild elephants, gaur, wild boar, deer and sometimes peacocks. A complex and well maintained system of small canals distributes water from the Manalar to irrigate the fields.

Muduvankudi is a neighboring village inhabited by Muduvar (Muthuvar), and is a 15-minute trek from Manjampatti.

Mungilpallam

Mungilpallam (Moongilpallam) village at 1,080 metres (3,540 ft), at the headwaters of the TenAr, the third village going up the valley, is a hamlet of just 20 houses of Pulaiyar people (pop: m-22, f-18), on the north side and above the Kumbaar stream. They practice some shifting cultivation on their south facing slope. There is a steep cliff trail from here which leads east to Kumboor village at the end of the road from Kodaikanal.[9]

There are 24 Muduvan and Paliyan families living there. They were said to have migrated from Manjampatti 200 years ago because of their fear of herds of wild elephants. They originally lived in caves. They eat wild roots, maize, fruits from wild plants, honey and bamboo rice. Their limited income comes from selling bamboo products and lemon grass oil, which they spend to buy rice from other villages. These people are nature worshippers. They do not worship regularly or have a particular place of worship but have a sacred area in their village. They visit this area to celebrate the harvest festival Pongal and the rain (Mari) festival, during which they sacrifice a goat.

They believe that diseases are manifestations of punishment inflicted by God. Till recently they only took native medicines. A witch doctor from the community was summoned for assessment and further treatment of serious illness. If the witch doctor's said the patient would die, food and medicines were withdrawn and the patient kept in a small hut away other until he or she died. In 2005, more than 50% of the children here suffered from severe chronic malnutrition.[20]

Since 1995, a registered Christian charity "Tribal Education and Medicare Vision" (Team Vision) has assisted the villagers to get identity cards and ration cards from the Revenue Department and Civil Supplies Department. Also, corrugated steel sheets were provided for home roofing. 18 new huts were erected in a new location in 1999. The Forest Department helped the villagers lay stones on the tortuous way to the village. They also erected two solar lamps. A kindergarten school was started and 20 children were enrolled in 1998. In 2005, 9 children from Mungilpallam were attending elementary and secondary school in Kodaikanal.[21]

Maangapaarai is another remote settlement and highly inaccessible because of bison attacks.

Geography

This Valley forms the southeast part of Anaimalai Reserve Forest, in Udumalaipettai Block, Coimbatore District,[22] about 13 km south of Amaravathi Reservoir and Dam on SH 17 and 30 km West of Kodaikanal at the western border of Dindigul District in the Palni Hills of the Western Ghats mountain range. Central location is . Elevation ranges from

- 2,327 metres (7,635 ft) at Vellari Malai peak towering over the valley

- 1,725 metres (5,659 ft) at Kumbur village on eastern ridge (outside IGWSNP)

- 1,640 metres (5,380 ft) at Mannavanur village sitting to the south east on a small plateau overlooking the valley (outside IGWSNP)

- 675 metres (2,215 ft) at Alanthoni Falls, 20 metres (66 ft) tall, on Ten Ar River west of Manjampatti Village

- 473 metres (1,552 ft) lowest point in the valley at the Amaravathi River

Peaks

The valley is surrounded by a ridgeline connecting several prominent peaks listed in order clockwise from the northwest corner. Starting at the Amaravathy River the ridge climbs to

- Tavatti Malai 943 metres (3,094 ft)

- Unnamed 1,700 metres (5,600 ft)

- Chinna Mudi Malai 1,836 metres (6,024 ft)

- Mudian Malai 1,836 metres (6,024 ft),

- Unnamed 1,793 metres (5,883 ft)

- Pappalamman Malai 2,201 metres (7,221 ft)

- Vellari Malai 2,219 metres (7,280 ft)

- Unnamed at Kilanavayal 2,350 metres (7,710 ft)

- Paratumba 2,260 metres (7,410 ft)

- Kalabhaathur Malai 2,066 metres (6,778 ft)

- Kadavaari 2,112 metres (6,929 ft)

- Vellingiri Malai 1,769 metres (5,804 ft)

- Jambu Malai 1,395 metres (4,577 ft)

- Palappatti 1,357 metres (4,452 ft) .

From here the ridge drops to the Amaravathi River.[5]

The western ridge of Manjampatti Valley extends 2 km into the easternmost area of Idukki District, Kerala and adjoins the 90 km2 Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary.[23]

Rivers

The Manjampatti Valley catchment basin drains into the Chinnar River from the Athioda Stream and to the Amaravathi River from the Kajadaikatti Odai Ar and Ten Ar Rivers 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) to the east.

Athioda is the north to south political and physical boundary for 1.584 miles (2.549 km) between Tamil Nadu and Kerala between the end of the Pambar River and the top of Jambumalai peak at the trijunction of Coimbatore and Dindugul Districts and Kerala State. (This peak is locally known as Chinna Chambu Malai).[23] The top of the ridge to the west above Athioda is the western limit of the catchment. Thus, the western edge of Manjampatti valley extends up to 2 km into Kerala. Athioda stream joins the Pambar River at the point they both join the Chinnar River at the north west corner of the Valley. West of this point, the Chinnar River forms the boundary between the Indira Gandhi National Park in Tamil Nadu and the Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary in Kerala. East of this point, the Chinnar river becomes the Amaravati River in Tamil Nadu.

The Ten Ar River is fed from most of the valley by the Kumbar stream, the Manalaar River ("sand river"), the Kalyanivalasu Odai and other smaller tributaries from the higher forests and sholas to the east. At the northwest end of the valley, the Ten Ar is joined by the Varavandi Odai stream flowing from a smaller adjacent valley to the east and soon joins the Amaravati River .8 km (0.50 mi) down stream to the west. The Amaravati River then flows north to the Amaravathi Reservoir and Dam and then to the Cauvery River.[5]

The Kudiraiyar River basin, including Kukkal village, is just over the northeast ridge of the valley behind Vellari Malai.

Wildlife

Manjampatti Valley currently supports stable breeding populations of several large mammal species including apex predators critical to healthy populations of smaller animals.

In colonial times Indian tigers (Tamil: puli or புலி ) were common in this area and as recently as the 1950s the Raja of Puthukkottai would go out from his house in Kodaikanal and hunt them. At least one tiger has been shot here within the past fifty five years.[24] Two tigers, a male and a female, were sighted and recorded in the 2007 wildlife census. Tiger populations in the adjoining areas of IGWS&NP and the nearby Kalakkad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve could expand back into this area if they and their prey species were better protected.

The census estimated 10 to 20 panthers (Tamil: sirutthai) living in the Manjampatti Valley. Wild Indian elephants roam over the whole valley. Sloth bears (Tamil: karadi) are sighted every year in the upper forests of Manjampatti valley. Nilgiri tahr (Tamil: varaiaadu) live especially on the spectacular high rocky peaks around the valley, as Mudimalai, Jambumalai, and Attumalai, though they may also be seen in the valley forests. There are several herds of gaur (popularly called bison) (Tamil: kaattu erumai, "forest buffalo") in the valley. Earlier the area was well known for Manjampatti white bison. This possible sub-species has recently been seen and photographed here by Forest Department staff.

Wild boar (Tamil: kaattu panri) live all over the Palani Hills (Tamil: பழனி) and in Manjampatti Valley, where one can frequently see holes in the ground where they have dug for edible roots. The valley has the large mountain squirrel (Tamil: malai-anil) and the ash-colored squirrel (Tamil: saambalnira anil).

There are wild peacocks, jungle fowl, and many other bird species enumerated in the Wildlife Census.[9]

There are no known studies of the many reptiles, amphibians, insects, invertebrates or plants living in the valley.

Visitor information

Manjampatti valley is a core zone of the Indira Gandhi National Park. Tourism, hiking, camping and non-resident visitation of the villages is prohibited. A permit is required for serious researchers to work inside the valley.

There is a well laid-out park nearby at the Amaravathi Dam where one may climb steep steps on the dam to have a picturesque view north of the plains below and south to the Anaimalai Hills, Manjampatti Valley and Palni Hills above. This place is being developed as a District Excursion Centre for tourism.[25] The park and adjacent crocodile farm are open every day from 9.00 A.M. to 6.00 P.M. Entry fees are 0.50 paise per adult and 0.25 paise per child (below 12 years).

Travel by road From Coimbatore – via Pollachi and Udumalpet to Amaravathynagar is 96 km (60 mi).

Accommodation is available for four persons, with advance reservation, at a forest rest house near the crocodile farm. Rent is Rs.150 per day for two persons per suite.

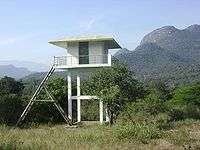

The Sarakupatti Watchtower is a small bare concrete room on an 8 m tower where one can go and wait to see animals. It has a fine view of the whole valley. It is located 1/2 km east of SH-17, 1/2 km north of Chinnar River checkpoint.[9] It is available for overnight lodging. Advance booking is required.

Contact:

- Forest Range Officer, Amaravathy Range, Amaravathy nagar, Ph. No. 94434 96413

- Wildlife Warden, Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary and National Park, 365/1 Meenkarai Road, Pollachi-1, Ph. No. 04259 225356, Email: IGWLSNPPOY@rediffmail.com

Gallery

- Talinji temple ruins

- Talinji temple ruins

- Sacred place at Talinji

- 3 deities at Talinji temple ruins

- Pieces of broken deities at Talinji

- View of Jambu Malai (1395 m) from Manjampatti APC showing fields of butter beans

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manjampatti Valley. |

- Ganeshan, IFS, Thiru V. (20 December 2006). "Management Plan for Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary and National Park, Pollachi, for the period 2007-2008 to 2011-2012". Dharmapuri, Tamil Nadu: Tamil Nadu Forest Department: 1–267. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - The Hindu, Forest personnel conduct raid, seize ganja; 3 July 2004 Forest personnel conduct raid, seize ganja

- Tamil Nadu Forest department, Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary Archived 3 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- World Commission on Protected Areas

- Department of Science and Technology, Survey of India, Topographical map, Amaravathi Range, scale 1:50,000

- Mathur, Dr. P.K. & Tripathi, Dr. Anshuman, Management of Forests in India for Biological Diversity and Forest Productivity–A New Perspective: Phase-II, #26. 01.09.2004 To 31.03.2007, p.34 fig.3.2., (warning: large 2MB file)Management of Forests in India

- U.S.D.A. Forest Service/Asia/archives/India, Sustainable Forestry Practices - Management of Forests in India for Biological Diversity and Forest Productivity Sustainable Forestry Practices

- Conservator of Forests, Coimbatore Circle, Trichy Road, Coimbatore. Wildlife Warden Archived 27 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Maloney Clarence ed, Contributions by R G Sekar, Forester; T K Subramaniam, Forest Guard; B Nagarajan, Forest Watcher; V Ganesan, Forest Watcher; S Rajan, Headman of Thalinji village; Gopal, Headman of Manjampatti village; Appunan, a Muthuvan (2 February 2008). Written at Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu, India. text (ed.). "Manjampatti Valley in the Palani Hills of South India: Its People and Environment". KodaiTalkEase. Yahoo Groups (published 8 February 2008). 2008 (#14189): 1–12.

|contribution=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) - "Tribal Development in India: A Case Study", Soundarapandian M., Anmol Publications PVT. LTD., ISBN 81-261-0723-5, 2001, pp. 135-147.partial text Tribal Development in India

- Sajeev T.K. et al., Management of Forests in India for Biological Diversity and Forest Productivity- A New Perspective WII-USDA Forest Service Collaborative Project Grant No. FG-In-780 (In-FS-120), Volume III Anaimalai Conservation Area (ACA) pp 169 - 190.Anaimalai Conservation Area Archived 16 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Gardner, Dr. Peter, Bicultural Versatility as a Frontier Adaptation among Paliyan Foragers of South India, 2000 Paliyan Foragers of South India

- Gardner, 2000, Excerpts Excerpts

- Aparna Narayanan & Bhaskar Venkateswaran, Trichirapalli Rural and Urban Welfare Development Educational Society (TRUWDES), Site visit to school for tribal children in Manjampatti village in Kodai Hills run by TRUWDES, 2007-6-26

- OurVillageIndia.org, Mannavanur Village 2007

- Medhaug

- Directorate of Rural Development, Government of TamilNadu Group of the Household

- "Census India: Tamil Nadu villages, Mannavanur". Census of India 2001. Government of India. 27 May 2002. p. 1. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- R.Vasuki, I.A.S., District Election Officer & District Collector, 16/07/2008, Dindigul, List of Polling Stations for 127 Palani Assembly Segment within the 22 DINDIGUL Parliamentary Constituency, Polling station No. 205 Archived 9 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Medhaug Endre, Faculty of Medicine, Trompso, Norway, Malnutrition in the Children around Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu, India June 2005, p. 35

- Lawrence Dr. Bevin G., orphanage.org Team Vision Children's Home 2005-7-29

- GIS DIVISION - National Informatics Centre-Tamil Nadu, Map: Coimbatore District, Udumalaipettai Block, Anaimalai Reserve Forest Map, Anaimalai Reserve Forest Archived 14 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary, Management Plan (2002-2011)". Department of Forests and Wildlife, Government of Kerala. 2007. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- Sherman Marcus Manjampatti Valley Notes Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, (2007)

- coimbatore.com, Around Pollachi- Anamalai Wildlife Sanctuary