Manhattanville College

Manhattanville College is a private liberal arts college offering undergraduate and graduate degrees in Purchase, New York. Founded in 1841 at 412 Houston Street in lower Manhattan, it was known initially as "Academy of the Sacred Heart", then later as "Manhattanville College" after 1847. In 1917, the academy received a charter from the Regents of the State of New York to raise the school officially to a collegiate level granting degrees as the "College of the Sacred Heart". The school moved to its current location further north, in a suburb beyond New York City in Purchase, New York, in 1952. It is near the hamlet of Harrison in Westchester County.

| |

| Motto | In Exultatione Metens |

|---|---|

| Type | Private coeducational |

| Established | 1841[1] |

| Endowment | $31.2 million (2019)[2] |

| President | Michael E. Geisler |

| Provost | Louise H. Feroe |

Academic staff | 114 (full-time)[1] |

| Students | 2,492 |

| Undergraduates | 1,588[1] |

| Postgraduates | 904[1] |

| Location | , , United States |

| Campus | Suburban; 100 acres (0.40 km2)[1] |

| Athletics | 21 NCAA Division III sports teams |

| Colors | Crimson and White |

| Mascot | Valiant |

| Website | mville |

Approximately 1,600 undergraduate and 900 graduate students attend Manhattanville, with students coming from 45+ countries and 35+ American states.[1]

The architectural and administrative centerpiece of the Manhattanville campus is Reid Hall (1864) which was named after Whitelaw Reid, publisher and owner of the New-York Tribune, one of the leading newspapers in the nation for a century. On either side of Reid Hall stand academic buildings on one side and on the other residence halls around a central quad designed by the landscaping / architect Frederick Law Olmsted, also the designer of New York's landmark Central Park in the 1850s and 1860s. The Manhattanville community regards the central quad and buildings as representing the academic vision of the college's commitment to integrated learning and centered strengths. Other historic buildings include the Lady Chapel, the President's Cottage known as the Barbara Debs House, the old Stables, and Water Tower.

History

The Academy of the Sacred Heart (1841–1917)

Manhattanville traces its origins to an Academy of the Sacred Heart founded over 175 years ago on the Lower East Side of New York City. In August 1841 the Society of the Sacred Heart (RSCJ), a Catholic religious order dedicated to the education of young women, established an academy at 412 Houston Street in the tightly packed warren of narrow streets in the southeast corner of Manhattan Island facing the East River.[3] In September 1844 the boarding school moved to Ravenswood in the Astoria section of Queens. However, within two years the location proved too remote.[4] In 1847 the growing Academy relocated to the former estate of Jacob Lorillard in the village of Manhattanville on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. At that time the town was still eight miles north of New York Town / City, still clustered around the south end at the Battery of Manhattan Island[5] By the time of the American Civil War, (1861-1865), the Manhattanville Academy counted 280 girl pupils. The Academy was always diverse with a substantial proportion of the student body consisting of recent immigrants from Latin America and Europe.[6] In 1880, the Academy began offering a two-year post-high school program for its young women students, foreshadowing a future in higher education.

The College of the Sacred Heart (1917–1937)

In the early 20th century, higher education opportunities for women increased as many formerly academies, seminaries, institutions and lower schools transitioned to the status of colleges.[7] Shortly before the United States declared war on the German Empire and entered the First World War, on March 1, 1917 the Academy of the Sacred Heart in Manhattanville received a Provisional Charter from the Regents of the State of New York to offer undergraduate degrees as "The College of the Sacred Heart". The first baccalaureate degrees were granted in 1918. The Absolute Charter was signed May 29, 1919. As the college grew, the city of New York also expanded northward, toward the far north end of Manhattan Island towards the Harlem River transforming the surrounding area from a rural village to diverse residential/commercial communities of Manhattan bordered by the Harlem and Morningside Heights neighborhoods. In 1935, The College of the Sacred Heart was accredited by the prestigious Association of American Universities.[8] The name was officially changed to "Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart" in 1937.[9]

Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart (1937–1966)

In the 1930s, the Manhattanville student body consisted of approximately 200 female students. Though small, the college made headlines across the country for taking a strong position promoting racial equality decades before the Civil Rights Movement of the late 1950s, into the 1960s and 1970s. In May 1933, students created the "Manhattanville Resolutions" a document that pledged an active student commitment to racial justice.[10] This commitment was tested when the first Negro woman student was admitted to the college in 1938. Alumnae response to a racially integrated but all-female student body was mixed and somewhat controversial for a time.[11] While the vast majority of letters praised Manhattanville for its courageous action, College President Grace Dammann, RSCJ, viewed the negative responses as an opportunity to open hearts and minds. At the annual Class Day reunion on May 31, 1938, she delivered a passionate speech entitled "Principles Versus Prejudices." She stated that education is the key to rising above prejudices.

"The more we know of man’s doing and thinking throughout time and throughout the world’s extent, the more we understand that beauty and goodness and truth are not the monopoly of any age nor of any group nor of any race.[12]"

The speech went on to be published in several national publications and established Manhattanville as a leader in higher education and human rights.[13] When President Dammann died suddenly in 1945, The New York Times obituary summarized her life's work with the headline, "Mother Dammann, College President: Head of Manhattanville Since 1930 Dies--Champion of Racial Equality."[14] Manhattanville would continue its work in social action first through the National Federation of Catholic College Students and to this day with the Duchesne Center for Religion and Social Justice and the Connie Hogarth Center for Social Action. Mary Louise (Mamie) Jenkins, RSCJ was the first African American student to graduate from Manhattanville and June Mulvaney was the first African American student to major in Russian at Manhattanville.[15][16]

As was the case for many colleges following World War II, neighboring City College of New York (C.C.N.Y. - part of the City University of New York) struggled to accommodate the growing college student population o. its campus. In 1946, the Mayor of New York City formed a special commission to investigate the resource needs of the city's public education institutions. Their recommendations would have particularly extensive ramifications for the future of the neighboring Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart.

In February 1949 The New York Times reported that City College was campaigning to acquire the Manhattanville campus to expand their facilities.[17] The same month, C.C.N.Y. distributed a pamphlet entitled "No Other Place to Go: A City College Plea for Purchase of the Manhattanville Property." The New York City Board of Estimate agreed and deeded the campus to City College via the legal process of condemnation and eminent domain.[18] In September 1949, the Manhattanville Board of Trustees purchased the Whitelaw Reid Estate, north of the city in suburban Westchester County. The next two years saw condemnation proceedings work through the New York State Supreme Court system. Manhattanville was eventually given near $8.8 million ($8,808,620) for the Manhattan campus and buildings.[19] A groundbreaking ceremony was held at the new campus near Harrison, in Purchase, New York on May 3, 1951. The new campus with its buildings were renovated and other construction was completed in October 1952.[20]

Manhattanville College (1966–present)

With additional facilities and space to grow, the student population increased from 400 women students in 1950 to 700 students by 1960. Over the course of the next decade, the student population doubled once again, reaching 1,400 students by 1970. Manhattanville was a microhistory of the societal transformation in the Roman Catholic Church, higher education, and American society as a whole during the 1960s. In 1966 the college Board of Trustees voted to amend the school charter and remove the words "of the Sacred Heart" from the official college name. This marked an important moment in the secularization of the college. Between 1966 and 1970, the Manhattanville administration oversaw the gradual removal of Catholic symbols and traditions from the campus. Although the college had been operated by an independent Board of Trustees since its founding in 1841, it was strongly identified with the Roman Catholic Church, and these changes were difficult for the community. By 1969, the College Charter was expanded to include the admitting education of both women and men. The first coeducational freshman class entered Manhattanville in August 1971.

In 1973 the student academic experience evolved due to an important campus study funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Interviews with the Manhattanville community led to the development of the Portfolio System, a personalized and guided self-assessment charting the development of each student. Today the ATLAS program continues this tradition. In 1965 the college introduced its first graduate program, a Masters of Arts in Teaching. The fifty years since have seen a remarkable growth of graduate programs. Since 1993, the School of Graduate and Professional Studies, now the School of Business, has developed masters and certificate programs in a variety of professional and business fields. In 2012 Manhattanville's Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing Degree Program was formally approved. The first doctoral program was introduced in 2010 with the Ed.D. in Educational Leadership from the School of Education.[21]

Presidents

The university has had 13 presidents and one interim president:[22]

- Mary Moran, RSCJ (1917–1918)[23]

- Ruth Burnett, RSCJ (1918–1924)

- Charlotte Lewis, RSCJ (1924–1930)

- Grace Dammann, RSCJ (1930–1945)

- Eleanor O'Byrne, RSCJ (1945–1965)

- Elizabeth McCormack (1965–1974)

- Harold Delaney (1974–1975)

- Barbara Knowles Debs (1975–1985)[24]

- Jane C. Maggin (acting interim) (1981–1982)

- Marcia Savage (1985–1995)

- Richard Berman (1995–2009)

- Molly Easo Smith (2009–2011)[25]

- Jon Strauss (2011–2016)

- Michael E. Geisler (2016–present)

Campus

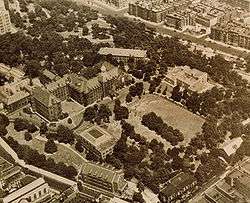

Convent Avenue Campus (1847–1952)

Manhattanville derives its name from its location between 1847 and 1952. The school, at the time still an Academy, purchased the Jacob Lorillard Estate in 1847 in a rural village called Manhattanville.[26] Over the next century New York City expanded, transforming the area from a farming village to a neighborhood in West Harlem.

The campus was located between 130th and 135th streets. The eastern border was Convent Avenue and its western border St. Nicholas Terrace. In 1949 proceedings began to incorporate the campus into the existing City College campus. Today it is known as the South Campus of City College. The final remaining buildings from the Manhattanville era are Park Hall (then known as Benziger) and Mott Hall (the Parish School during Manhattanville's time).[27]

Reid Estate (1860-1949)

Manhattanville purchased its current 100-acre campus in 1949. The first owner of the parcel of land was Ben Holladay who bought the estate in the 1860s and named its Ophir Farm after a silver mine in Nevada.[28] The Holladay family built a mansion called Ophir Hall, family chapel, and several outbuildings. However, after several family deaths and financial difficulties, Ben Holladay left the estate in 1873.[29]

In 1888 Whitelaw Reid and his wife Elisabeth Mills Reid purchased the property. Whitelaw was editor of The New York Tribune and served various political positions including ambassador to France and England. Elisabeth was the daughter of Darius Ogden Mills, founder of The Bank of California. The Reids remodeled the existing Ophir Hall and outfitted it with the latest home luxuries, including electricity. However, shortly before completion, faulty wiring sparked a fire that destroyed the home on July 14, 1888. The Reids rebuilt under the direction of the famed architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White. This home was designed in the style of a gothic castle and built onto the existing foundation. The Castle was completed in 1892.[30] A three-story addition including the East Library and West Room was completed in 1912.[31] Whitelaw Reid died while serving as the ambassador to England in 1912. Elizabeth Mills Reid died in 1931 and the contents of the house were auctioned in 1935. In 1947 the Reid family placed the estate for sale.

Reid Castle was dedicated to Elisabeth Mills Reid on September 19, 1969. In 1974 the U.S. Department of the Interior placed the building on the National Register of Historic Places in recognition of its historical and architectural significance.[32]

Purchase Campus (1952–present)

The new Manhattanville campus was completed in 1952 with six buildings: a renovated Reid Castle for use as an administration building, the library, the academic building, Brownson Hall; the music building Pius X Hall; Benziger Dining Hall, and Founders Dormitory.

The increasing student population led to the addition of the Spellman Hall dormitory in 1957. The Kennedy Gymnasium, also completed in 1957, was made possible through a grant from the Lieutenant Joseph Kennedy Jr. Foundation. The Kennedy family dedicated the gymnasium in honor of their daughter, Kathleen, Marchioness of Hartington. The dedication for both the Kennedy Gymnasium and Spellman Hall were held October 27, 1957, and was presided over by Francis Cardinal Spellman, Archbishop of New York. In attendance were Joseph P. Kennedy, Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy ‘11, Jean Kennedy Smith ‘49, and Ethel Skakel Kennedy ‘49. Edward M. Kennedy delivered the dedication speech.[33]

For the first decade in Purchase, the campus worship space was located in the West Room. The Chapel was completed in 1963 and named in honor of President Eleanor O’Byrne, RSCJ. O’Byrne is the longest serving president with an administration lasting from 1945 to 1966. Dammann and Tenney Halls were the final residence buildings completed in 1966. In 1991 forty-eight faculty and staff housing units added a new dimension to the Manhattanville campus community.[32]

On September 26, 2006 the Manhattanville community dedicated the Ohnell Environmental Center. The center includes a classroom housed within a LEED-compliant, non-invasive structure designed by Maya Lin, architect of the Vietnam War Memorial. The project also included a restoration of the Holladay Stone Chapel, which features new stonework and a glass roof providing a unique reflective space on campus. In 2008 the Berman Center was completed.[34] This building currently houses the Communication and Media Department, the Berger Art Gallery, the student-run radio station MVL; the school newspaper, Touchstone; a dance studio and a fitness center. The past several years have seen a variety of campus renovations including improvements to the library, dining facilities, gym, athletic fields, tennis courts and campus walkways. In 2012 the college welcomed Heritage Hall, a permanent exhibition of the college's history.

Academics

Manhattanville is a liberal arts institution, offering the four-year Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science, Bachelor of Fine Arts and Bachelor of Music degrees to undergraduate students and the M.A., M.S., Ph.D. and Ed. D. for graduate students. Undergraduates can choose from 45 majors and minors, while graduate students can explore 75 graduate degrees and advanced certificates. Students are also free to design special majors or engage in dual majors. The most popular majors for undergraduates are Business, Management, Psychology, Communications, English, Studio Art, and History.

Rankings

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[35] | 512 |

| THE/WSJ[36] | 501-600 |

| Regional | |

| U.S. News & World Report[37] | 73 |

| Master's University class | |

| Washington Monthly[38] | 180 |

The Castle Scholars Honors Program

The Castle Scholars Honors Program at Manhattanville College seeks to challenge high-achieving students and encourages them to explore new areas of interest beyond the usual intellectual parameters during their entire undergraduate career. This selective program limits admission to the top ten percent of each incoming class. Castle Scholars Honors Students benefit from rigorous, intellectually stimulating, interdisciplinary seminars, all of which are taught by full-time faculty. Castle Scholars can also apply for special funding to complete independent Honors research and creative projects, allowing them to design, implement, and achieve the ambitious goals they set for themselves. Castle Honors students also learn how to become effective leaders and give back to the Manhattanville community by organizing Human Rights Awareness Day each fall, and the Undergraduate Research and Creative Achievement Fair each spring.

Pius X School of Liturgical Music

The Pius X School of Liturgical Music was opened in 1916 as part of the college. It was founded by Justine Ward, who had developed teaching methods for Gregorian chant emulating the techniques of the monks in Solesmes, and by Mother Georgia Stevens, RSCJ, a musician and Roman Catholic nun.[39] Faculty over the years included Ward, Achille Bragers and André Mocquereau. Thousands of music teachers studied at the school, including Cecilia Clare Bocard and Thomas Mark Liotta. The school's namesake was Pope Pius X, a devotee of sacred music who initiated reform of the liturgy in the 20th century. The institute closed in 1969. In 2010 a Gregorian Chant, held in Pius X Hall, as part of Inauguration festivities for the previous President, saw a packed auditorium of alumni, students, and faculty.

Graduate programs

In addition to its 45 majors and minors of undergraduate study, Manhattanville College offers graduate master's degrees in ten areas of study and an Ed.D. in the School of Education. The School of Business offers Master's of Science degrees in Human Resource Management and Organizational Effectiveness, Business Leadership, Marketing Communication Management, International Management, Sport Business Management, and Finance. The college also offers accelerated BS degrees as part of the APPEAL (Accelerated Professional Programs for Evening Adult Learners),[40] and a range of dual degree programs. The School of Business' Institute for Managing Risk and the Women's Leadership Institute provide academic resources skills and events to serve the needs of individuals, organizations and businesses.[41]

Manhattanville's 36-credit Master of Fine Arts in creative writing program is open to graduates of accredited colleges and universities who demonstrate a strong potential in writing and critical thinking. Students are admitted to the program primarily on the strength of the writing they submit as part of the application process.

Nursing school

In fall 2020 the school is to establish a nursing program.[42] In 2019 the school began exploring this possibility as College of New Rochelle had permanently closed.[43]

Manhattanville Library Rare Book and Manuscripts Room

The Rare Book and Manuscripts Room preserves both manuscripts and printed materials from the Manhattanville College Library. The rare book collection consists of approximately 2,400 titles that span the history of the book in the United States and Europe. Subject fields represented include history, religion, literature, biography, and philosophy. The collection also includes other formats such as periodicals, Jewish pamphlets, government documents, maps, and manuscripts. Particularly noteworthy are five incunabula, and several bound manuscript volumes. The latter include individual collections of psalms and prayers intended as an aid to private devotion, known as the Books of Hours. The most notable of these is the Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis, Cum Calendario—also known as the Manhattanville Book of Hours.[44]

Student life

Athletics

| Manhattanville Valiants | |

|---|---|

| |

| University | Manhattanville College |

| Conference | Skyline UCHC (Hockey only) NECC (Field Hockey only) |

| NCAA | Division III |

| Athletic director | Julene Caulfield |

| Location | Purchase, New York |

| Varsity teams | 20 (9 Men & 11 Women) |

| Basketball arena | Kennedy Gymnasium |

| Soccer stadium | GoValiants.com Field |

| Mascot | Valiant |

| Nickname | Valiants |

| Colors | Crimson and White |

| Website | www |

Manhattanville is a member of NCAA Division III, competing primarily in the Skyline Conference, the United Collegiate Hockey Conference (men's & women's hockey)[45], and the NECC (Woman's Field Hockey)[46]. The department has added eight teams since 2007 and currently sponsors 20 varsity sports: men's and women's basketball, cross country, hockey, indoor track, lacrosse, outdoor track, and soccer; baseball, softball, men's and women's golf, field hockey, and women's volleyball. Men's and women's tennis[47] will begin in 2018–19.

In May 2018, Manhattanville announced that they would leave the MAC Freedom Conference and return to the Skyline Conference for the 2019–20 academic year. Manhattanville was a charter member of the Skyline before leaving to join the MAC in 2007.[48]

Publications

The Touchstone[49] is the oldest newspaper serving the Manhattanville community; the national literary magazine Graffiti is also published at Manhattanville.

Notable alumni

- Karen Akers – Singer, actress, Theatre World Award winner and Tony Award nominee (Nine, Grand Hotel, Heartburn, The Purple Rose of Cairo)

- Kathleen Sullivan Alioto – Educator, politician, Chairperson of the Boston School Committee

- Ann Bermingham – Professor emeritus of art history at the University of California, Santa Barbara

- Cecilia Clare Bocard, S.P. – Musician and composer of works for organ, piano, and chorus

- Sally Bott – Group Human Resources Director of Barclays

- Jamaal Bowman - Educator and presumptive Democratic candidate seeking to represent NY's 16th congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives

- Matt Braunger – Actor, writer and stand-up comedian (MADtv)

- Sarah Brownson – Writer, daughter of Orestes A. Brownson

- Meg Bussert – Broadway actress, singer, and academic (The Music Man, Brigadoon, Camelot)

- Sila Calderón – Politician, businesswoman, and former Governor of Puerto Rico

- Adele Chatfield-Taylor – President and CEO of the American Academy in Rome, 1988-2013

- Sook Nyul Choi – Children's author

- Christine Choy – Documentary film maker (Who Killed Vincent Chin?)

- Mary T. Clark, RSCJ – Academic, scholar of the history of philosophy and civil rights advocate

- Carlon Colker, M.D. – Physician and dietary supplement industry consultant

- James Badge Dale – Film and television actor (24, Rubicon)

- James de Givenchy – Jewelry designer and owner of the jewelry company, Taffin

- Rosario Ferré – Writer, poet, essayist, professor at the University of Puerto Rico

- Anita Figueredo – Surgeon and philanthropist

- Lindsay Barrett George – Award-winning illustrator and author of children's books

- Katharine Gibbs – Founder of Gibbs College, for-profit institution founded in 1911

- Mindy Grossman – CEO of HSN, Inc., ranked #22 in Fortune 's Top People in Business, 2014

- Mary Hamilton (activist) – Freedom Rider, Congress of Racial Equality field secretary, appelant in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, Hamilton v. Alabama (1964)[50]

- Jane Briggs Hart – aviator

- Marion S. Kellogg – First woman vice president of General Electric[51]

- Rose Kennedy – Mother of U.S. President John F. Kennedy

- Ethel Skakel Kennedy – Widow of U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy; founder of the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Center

- Joan Bennett Kennedy – Writer, musician, former wife of U.S. Senator Edward M. Kennedy

- Janice Lachance – CEO of the Special Libraries Association and former Director of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management

- Mickey Lang – professional ice hockey player for the Toronto Marlies

- Maria Elena Lagomasino – CEO of Asset Management Advisors, an affiliate of SunTrust Banks; director of The Coca-Cola Company; former Chairman and CEO of JP Morgan Private Bank; 2007 Hispanic Business Woman of the Year

- Sean Lavery – Composer; Director of Liturgical and Music Development at the Immaculate Conception Cathedral in Ozamiz in the Philippines; Director of Sacred Music at St Patrick's College, Maynooth, Ireland

- Hildreth Meiere – Architectural artist, muralist and mosaicist; first woman to win the Fine Arts Medal of the American Institute of Architects

- Daryl A. Mundis – Senior Trial Attorney at The Hague for the Slobodan Milošević trial

- Rosemary Murphy – Film, stage, and television actress (To Kill A Mockingbird, Walking Tall, Eleanor and Franklin)

- Josie Natori – President of The Natori Company

- Olga Nolla – Poet, journalist, resident writer at Universidad Metropolitana (UMET)

- Kitty Pilgrim – Emmy, Peabody, and Dupont award-winning CNN News anchor and correspondent

- Mary Perkins Ryan – a Catholic writer and educator.[52]

- Nancy Salisbury RSCJ – Educator and academic

- Dalmazio Santini – Composer

- Carol Sauvion – Executive Producer and Director, Craft in America, Peabody Award-winning, Emmy-nominated, PBS documentary series.

- Jane D. Schaberg – Feminist biblical scholar; Professor of Religious Studies and Women's Studies at the University of Detroit Mercy.

- Phyllis Shalant – Children's fiction and non-fiction author

- Eunice Kennedy Shriver – Founder and Honorary Chairman of the Special Olympics; Executive President of the Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. Foundation

- Maria Shriver – Former First Lady of California, noted journalist and activist.

- Barbara Boggs Sigmund – Former mayor of Princeton, New Jersey

- Tina Sloan – Film and television actress (Guiding Light)

- Jean Kennedy Smith – diplomat and former U.S. Ambassador to Ireland

- Nan A. Talese – Editor

- Brittany Underwood – Actress and Singer (One Life to Live and Hollywood Heights)

- Carmen Marc Valvo – Designer

- Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt – socialite, grandmother to Anderson Cooper

- Barbara Farrell Vucanovich – U.S. House of Representatives, Nevada 2nd District

- Patricia Nell Warren – Novelist (The Front Runner), essayist, lesbian and gay rights activist

- Kathleen Wilber – Professor of Gerontology, University of Southern California,[53]

References

- "Fast Facts". Manhattanville College. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- As of June 30, 2019. "U.S. and Canadian 2019 NTSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2019 Endowment Market Value, and Percentage Change in Market Value from FY18 to FY19 (Revised)". National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Garvey, RSCJ, Mary (1925). Mary Aloysia Hardey: Religious of the Sacred Heart 1809-1886. New York: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 78–84.

- Williams, Margaret (1942). Second sowing; the life of Mary Aloysia Hardey. New York: Sheed & Ward. p. 228.

- Williams, Margaret (1942). Second sowing; the life of Mary Aloysia Hardey. New York: Sheed & Ward. p. 240.

- Rebardy, Janet (1975). "A Brief Summary of the History and Contributions of the Society of the Sacred Heart in the Archdiocese of New York". Manhattanville College Special Collections.

- Byrne, Patricia (1995). "A Tradition of Educating Women: The Religious of the Sacred Heart and Higher Education". U.S. Catholic Historian. 13 (4): 52–59.

- Byrne, Patricia (1995). "A Tradition of Educating Women: The Religious of the Sacred Heart and Higher Education". U.S. Catholic Historian. 13 (4): 65.

- "Manhattanville Timeline". www.manhattanville.edu.

- "The Manhattanville Resolutions".

- "Letter of Protest, Anonymous Alumni Mailing". Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "Principles Versus Prejudices".

- "Manhattanville College of Sacred Heart Epitome of Liberal Interracial Educational Institution".

- "Mother Dammann College President". New York Times. 14 February 1945.

- "Catholic Digest, "Principles Conquers Prejudices," 1949 | Digital Culture". dcmny.org. Retrieved 2019-10-03.

- "Mary Louise (Mamie) Jenkins, RSCJ | RSCJ.org". asdf.rscj.org. Retrieved 2019-10-12.

- Fine, Benjamin (6 February 1949). "City College Seeking to Buy Near-by Manhattanville Plant". New York Times.

- "City Board Votes to Take Manhattanville College Site". New York Times. June 30, 1950.

- "City Buys College Paying $8,800,620: Manhattanville Campus". New York Times. June 14, 1952.

- "Manhattanville Timeline". Manhattanville College Library Special Collections.

- Wepner, Shelley B. (Fall 2010). "Greetings from the Dean" (PDF). Education is Life: School of Education Alumni Magazine.

- "Manhattanville College Presidents". Manhattanville College. Archived from the original on 2009-02-17. Retrieved 2014-08-16.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Residence Buildings". Manhattanville College. 2018-07-15. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- "An Acting President At Manhattanville Named by Trustees". New York Times. June 21, 1975. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

Dr. Barbara Knowles Debs, chairman of the art history department at Manhattanville College, was named acting president of the strife-torn institution today by the board of trustees.

- Joseph, George (May 7, 2010). "Molly Smith inaugurated as head of Manhattanville College". Rediff.com. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- Williams, Margaret (1942). Second Sowing: The Life of Mary Aloysia Hardey. New York: Sheed & Ward. p. 240.

- "The Lost World of CCNY: Architectural Gems of Our Past: South Campus". CCNY Libraries Exhibitions.

- Lucia, Ellis (1959). The Saga of Ben Holladay: Giant of the Old West. New York: Hastings House. pp. 189–192.

- Lucia, Ellis (1959). The Saga of Ben Holladay: Giant of the Old West. New York: Hastings House. pp. 320–321.

- Todd, Nancy E. (Spring 2004). "The Chapel at Reid Hall: History of Land of the Site Now Occupied by Manhattanville College, Purchase, N.Y.". The Westchester Historian. 80: 55–57.

- Duncan, Bingham (1974). Whitelaw Reid: Journalist, Politician, Diplomat. Athens: The University of Georgia Press. pp. 224–225.

- "The History of Reid Castle" (PDF). Manhattanville College. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- "Cardinal Spellman Presides at Dedication Ceremony". The Centurion. Manhattanville College Special Collections. 31 October 1957.

- "Campus Buildings - What's In A Name?". Manhattanville College Library Digital Collections and Exhibits.

- "America's Top Colleges 2019". Forbes. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- "U.S. College Rankings 2020". Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- "Best Colleges 2020: Regional Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- "2019 Rankings -- Masters Universities". Washington Monthly. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- Catherine A. Carroll, "Justine B. Ward and the Pius X School 1916-1931: Historical Outline", in Litjens/Steinschulte, Divini 121-124.

- steve.albanese (9 September 2015). "APPEAL- Adult Accelerated Degrees". Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- steve.albanese (8 February 2016). "Institutes". Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Lungariello, Mark (2020-01-24). "Manhattanville College nursing school to open in fall, months after closing of College of New Rochelle". The Journal News. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- Lungariello, Mark (2019-11-27). "Manhattanville looks to open nursing school in wake of College of New Rochelle's closing". The Journal News. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- "Media Services". mville.edu. Retrieved 2015-08-03.

- "Manhattanville Hockey to Join United Collegiate Hockey Conference in 2017-18". Manhattanvlle College. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- https://www.neccathletics.com/sports/fh/2018-19/releases/manhattanville

- "Manhattanville College". Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "Manhattanville to Join Skyline Conference in 2019-20 Academic Year". Skyline Conference. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "- TOUCHSTONE -". Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- "MARY HAMILTON WESLEY's Obituary on The Journal News". The Journal News. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "Marion S. Kellogg Obituary". The New York Times. September 8, 2004. Retrieved July 29, 2019 – via Legacy.com.

- "Mary Perkins Ryan". Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- "Faculty Profile". usc.edu. Retrieved 2015-08-03.