Malpas, Cheshire

Malpas is a small ancient market town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire West and Chester and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. The parish lies on the borders with Shropshire and Wales, and had a population of 1,673 at the 2011 Census. The name derives from Old French and means "bad passage".

| Malpas | |

|---|---|

St Oswald's Church, Malpas from the southwest | |

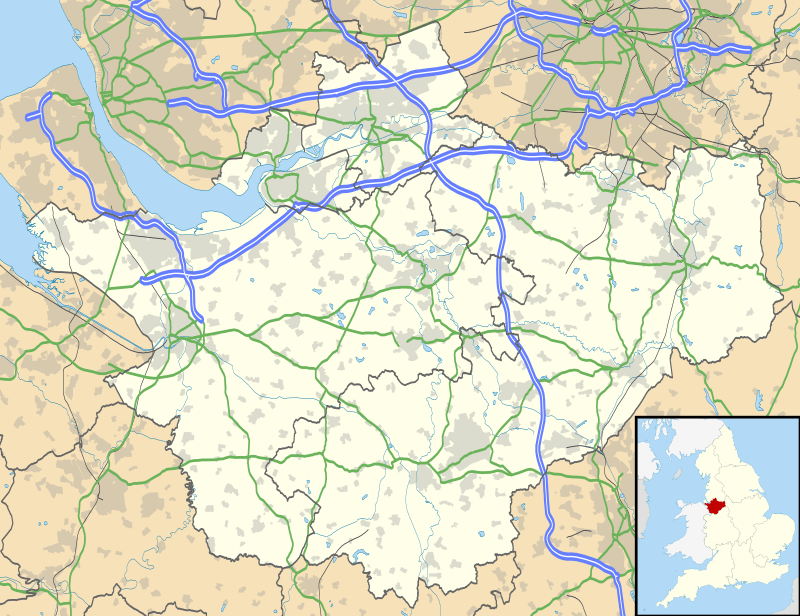

Malpas Location within Cheshire | |

| Population | 1,673 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SJ487472 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MALPAS |

| Postcode district | SY14 |

| Dialling code | 01948 |

| Police | Cheshire |

| Fire | Cheshire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

History

Roman

There is no evidence for Roman settlement in Malpas, but it is known that the Roman Road from Bovium (Tilston) and Mediolanum (Whitchurch) passes through the village.

Mercian

Dedications to St Oswald are thought to be associated with Æthelræd II (879–911), also known as Earl Aethelred of Mercia and Æthelflæd of Mercia (911–918); they are known to have encouraged the growth of this cult along the Welsh border in places such as Hereford and Shrewsbury. This may indicate that Malpas was not a Norman 'New Town', but an Anglo-Saxon burh.

Medieval (Norman 1066–1154)

After the Norman conquest of 1066 Malpas is recorded as being called Depenbech and is mentioned in the Domesday book of 1086 as belonging to Robert FitzHugh, Baron of Malpas. Malpas and other holdings were given to his family for defensive services along the Welsh border. The Cholmondeley family who still live locally at Cholmondeley Castle descended from Robert FitzHugh: Richard de Malpas, son of John de Malpas (originator of the Cholmondeley family who lived at Depenbach), married Letitia FitzHugh, daughter of Robert FitzHugh.[3]

A concentrated line of castles protected Cheshire's western border from the Welsh; these included motte-and-bailey castles at Shotwick, Dodleston, Aldford, Pulford, Shocklach, Oldcastle and Malpas. The earthworks of Malpas Castle are still to be found to the north of St. Oswald's Church.

Medieval (Plantagenet 1154–1485)

Malpas became more important when the western hundreds of Cheshire were detached to become part of Wales. By the late 13th century, Malpas became the most important settlement in the southern part of Broxton hundred. Develops significantly around the motte and church and becomes a market town – Malpas was granted a Market Charter for a weekly market and annual fair in 1281. The present church was built in the second half of the 14th century on the site of an earlier one, of which nothing remains. However, there is a list of earlier rectors. Extensive alterations were made in the late 15th century. The roof was removed, the side walls reduced in height and rebuilt with the current windows while the nave arcade was raised to its current height.

The town retains its general layout established in the medieval period. A possible reason for Malpas not undergoing intensive development is that Whitchurch, a major market town, was just 7 km (4.3 mi) away.[4]

Tudor – Elizabethan (1485–1603)

The seventh son of Sir Randolph Brereton of Shocklach and Malpas, Sir William Brereton, became chamberlain of Chester, and groom of the chamber to Henry VIII. He was beheaded on 17 May 1536 for a suspected romantic affair with Anne Boleyn. These accusations may have been politically motivated.

Civil War and the Stuarts (1603–1714)

Cheshire was strategically very important during the civil war as it controlled the North-South movement of troops from the west of the Pennines to the east of the Clwydian range – Chester, as the main port to Ireland was supremely important as Charles I had an army there. Another Sir William Brereton of Malpas and Shocklach was one of two Parliamentarian Generals responsible for the defeat of the Royalist Irish reinforcements at the Battle of Nantwich in January 1644 and later the siege of Chester, capturing it in February 1646.

Second World War

In 1940 during the Second World War, the Czechoslovak Army in exile was encamped in Cholmondeley Park.

Transport

The village was once served by the Whitchurch and Tattenhall Railway or Chester-Whitchurch Branch Line. The station was closed along with the entire line under the Beeching Axe in the 1960s.

Demography

According to the United Kingdom Census 2001 :

Governance

An electoral ward in the same name exists. This ward stretches north to Edge and south to Wigland. The total population of this ward taken at the 2011 Census was 3,975.[7]

Listed buildings

Religion

- Church of England, see: St Oswald's Church, Malpas

- Roman Catholic Church, St Joseph's Church.

- United Reformed Church, High Street Church.

- Malpas Elim Community Church, www.malpaselimcc.com

Notable people

- Ralph Churton, Anglican churchman and biographer

- Anthony Harvey, filmmaker, has been resident since 1968

- Bishop Reginald Heber (1783–1826), Bishop of Calcutta and poet

- Matthew Henry (1662–1714), Presbyterian minister and biblical commentator[8]

- Chris Stockton, former jockey, owner of rare cattle, BTCC racing driver

- Mark Rylands, Anglican Bishop of Shrewsbury 2009-18, Malpas resident 1961–1988

Education

- Primary School − Malpas Alport Endowed Primary School

- Secondary School − Bishop Heber High School, named after Bishop Reginald Heber

References

- "Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "Malpas Parish Council". Malpas Online. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- Burke's Peerage and Gentry, online http://www.burkes-peerage.net

- Shaw, Mike; Clark, Jo, Cheshire Towns Survey: Malpas – Archaeological Assessment, Cheshire County Council, p. 1, archived from the original on 16 July 2011, retrieved 23 December 2010

- "2001 UK Census Headcount for Malpas".

- "2001 UK Census People Statistics".

- "Ward population 2011". Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- British Listed Buildings: Cenotaph to Matthew Henry on Grosvenor Street Roundabout, Chester Castle, Matthew Henry's Birthplace

Further reading

- Churton, Ralph (1793) "A memoir of Thomas Townson, D.D., archdeacon of Richmond, and rector of Malpas, Cheshire", prefixed to A Discourse on the Evangelical History from the Interment to the Ascension published after Dr. Townson's death by Dr. John Loveday, Oxford, 1793.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malpas, Cheshire. |

- Malpas Community Website which includes sections on history, art, events, sports and social groups and businesses.

- Visions of Britain – Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales (1870–72)

- Visions of Britain, John Bartholomew, Gazetteer of the British Isles (1887)

- P. Carrington: Roman Cheshire

- K. Matthews: Saxon Cheshire

- The Malpas Legacy by Sam Llewellyn (Novel)