Mail coach

In Great Britain, Ireland, and Australia, a mail coach was a stagecoach built to a General Post Office-approved design operated by an independent contractor to carry long-distance mail for the Post Office. Mail was held in a box at the rear where the only Royal Mail employee, an armed guard, stood. Passengers were taken at a premium fare. There was seating for four passengers inside and more outside with the driver. The guard's seat could not be shared. This distribution system began in Britain in 1784. In Ireland the same service began in 1789, and in Australia it began in 1828.

A mail coach service ran to an exact and demanding schedule. Aside from quick changes of horses the coach only stopped for collection and delivery of mail and never for the comfort of the passengers. To avoid a steep fine turnpike gates had to be open by the time the mail coach with its right of free passage passed through. The gatekeeper was warned by the sound of the posthorn.

Mail coaches were slowly phased out during the 1840s and 1850s, their role eventually replaced by trains as the railway network expanded.

History in Britain

The postal delivery service in Britain had existed in the same form for about 150 years - from its introduction in 1635, mounted carriers had ridden between "posts" where the postmaster would remove the letters for the local area before handing the remaining letters and any additions to the next rider. The riders were frequent targets for robbers, and the system was inefficient.[1]

John Palmer, a theatre owner from Bath, believed that the coach service he had previously run for transporting actors and materials between theatres could be utilised for a countrywide mail delivery service, so in 1782, he suggested to the Post Office in London that they take up the idea. He met resistance from officials who believed that the existing system could not be improved, but eventually the Chancellor of the Exchequer, William Pitt, allowed him to carry out an experimental run between Bristol and London. Under the old system the journey had taken up to 38 hours. The coach, funded by Palmer, left Bristol at 4pm on 2 August 1784 and arrived in London just 16 hours later.[1]

Impressed by the trial run, Pitt authorised the creation of new routes. By the end of 1785 there were services from London to Norwich, Liverpool, Leeds, Dover, Portsmouth, Poole, Exeter, Gloucester, Worcester, Holyhead and Carlisle. A service to Edinburgh was added the next year and Palmer was rewarded by being made Surveyor and Comptroller General of the Post Office.[1]

Initially the coach, horses and driver were all supplied by contractors. There was strong competition for the contracts as they provided a fixed regular income on top of which the companies could charge fares for the passengers. By the beginning of the 19th century the Post Office had their own fleet of coaches with black and maroon livery.[2] The early coaches were poorly built, but in 1787 the Post Office adopted John Besant's improved and patented design, after which Besant, with his partner John Vidler, enjoyed a monopoly on the supply of coaches, and a virtual monopoly on their upkeep and servicing.[1]

The mail coaches continued unchallenged until the 1830s but the development of railways spelt the end for the service. The first rail delivery between Liverpool and Manchester took place on 11 November 1830. By the early 1840s other rail lines had been constructed and many London-based mail coaches were starting to be withdrawn from service; the final service from London (to Norwich) was shut down in 1846. Regional mail coaches continued into the 1850s, but these too were eventually replaced by rail services.[1]

Travel

The mail coaches were originally designed for a driver, seated outside, and up to four passengers inside. The guard (the only Post Office employee on the coach) travelled on the outside at the rear next to the mail box. Later a further passenger was allowed outside, sitting at the front next to the driver, and eventually a second row of seating was added behind him to allow two further passengers to sit outside. Travel could be uncomfortable as the coaches travelled on poor roads and passengers were obliged to dismount from the carriage when going up steep hills to spare the horses (as Charles Dickens describes at the beginning of A Tale of Two Cities). The coaches averaged 7 to 8 mph (11–13 km/h) in summer and about 5 mph (8 km/h) in winter but by the time of Queen Victoria the roads had improved enough to allow speeds of up to 10 mph (16 km/h). Fresh horses were supplied every 10 to 15 miles (16–24 km).[1] Stops to collect mail were short and sometimes there would be no stops at all with the guard throwing the mail off the coach and snatching the new deliveries from the postmaster.

The cost of travelling by mail coach was about 1d. a mile more expensive than by private stage coach, but the coach was faster and, in general, less crowded and cleaner. Crowding was a common problem with private stage coaches, which led to them overturning; the limits on numbers of passengers and luggage prevented this occurring on the mail coaches. Travel on the mail coach was nearly always at night; as the roads were less busy the coach could make better speed.[2]

The guard was heavily armed with a blunderbuss and two pistols and dressed in the Post Office livery of maroon and gold. The mail coaches were thus well defended against highwaymen, and accounts of robberies often confuse them with private stage coaches, though robberies did occur.[3] To prevent corruption and ensure good performance, the guards were paid handsomely and supplied with a generous pension. The mail was their sole charge, meaning that they had to deliver it on foot if a problem arose with the coach and, unlike the driver, they remained with the coach for the whole journey; occasionally guards froze to death from hypothermia in their exposed position outside the coach during the harsh winters (see River Thames frost fairs). The guard was supplied with a timepiece and a posthorn, the former to ensure the schedule was met, the latter to alert the post house to the imminent arrival of the coach and warn tollgate keepers to open the gate (mail coaches were exempt from stopping and paying tolls: a fine was payable if the coach was forced to stop). Since the coaches had right of way on the roads the horn was also used to advise other road users of their approach.[2]

History in Ireland

A twice-weekly stage coach service operated between Dublin and Drogheda to the north, Kilkenny to the south and Athlone to the west as early as 1737 and for a short period from 1740, a Dublin to Belfast stage coach existed. In winter, this last route took three days, with overnight stops at Drogheda and Newry; in summer, travel time was reduced to two days.[4]

In 1789, mail coaches began a scheduled service from Dublin to Belfast. They met the mail boats coming from Portpatrick in Scotland at Donaghadee, in County Down.[5]

By the mid-19th century, most of the mail coaches in Ireland were eventually out-competed by Charles Bianconi's country-wide network of open carriages, before this system in turn succumbed to the railways.[6]

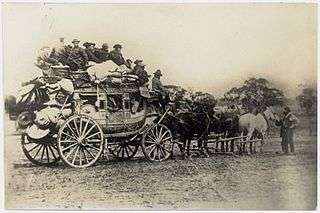

History in Australia

Australia's first mail coach was established in 1828 and was crucial in connecting the remote settlements being established to the larger centres. The first mail contracts were issued and mail was transported by coach or on horseback from Sydney to the first seven country post offices – Penrith, Parramatta, Liverpool, Windsor, Campbelltown, Newcastle and Bathurst. The Sydney to Melbourne overland packhorse mail service was commenced in 1837.[7] From 1855 the Sydney to Melbourne overland mail coach was supplanted by coastal steamer ship and rail. The rail network became the distributor of mail to larger regional centres there the mail coach met the trains and carried the mail to more remote towns and villages.[8]

In 1863 contracts were awarded to the coaching company Cobb & Co to transport Royal Mail services within New South Wales and Victoria. These contracts and later others in Queensland continued until 1924 when the last service operated in western Queensland. The lucrative mail contracts helped Cobb & Co grow and become an efficient and vast network of coach services in eastern Australia.

Royal Mail coach services reached their peak in the later decades of the 19th century, operating over thousands of miles of eastern Australia. In 1870s Cobb & Co's Royal Mail coaches were operating some 6000 horses per day, and traveling 28,000 miles weekly carrying mail, gold, and general parcels.

Some Concord stagecoaches were imported from the United States made in New Hampshire by the Abbot-Downing Company. This design was a 'thorough-brace' or 'jack' style coach characterized by an elegant curved lightweight body suspended on two large leather straps, which helped to isolate the passengers and driver from the jolts and bumps of the rough unmade country roads. Soon Australian coach builders using many of the Concord design features customized the design for Australian conditions.

Note

- England north of the river Humber

References

- "The Mail Coach Service" (PDF). The Royal Mail: Postal Heritage Trust. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2006.

- Paul Ailey (2004). "Mail Coaches". Bishops Stortford Tourist Information. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2006.

- "Broadside entitled "Robbery of the Mail Coach"". National Library of Scotland. 2004. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Connolly, Sean (2008). Divided Kingdom: Ireland 1630-1800. US: Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-19-954347-2.

- McCutcheon, William Alan; Dept. of the Environment (1984). The industrial archaeology of Northern Ireland. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 395. ISBN 978-0-8386-3125-6.

- Super, R.H. (1991). The Chronicler of Barsetshire: A Life of Anthony Trollope (reprint ed.). University of Michigan Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-472-08139-4.

- "INFANT SCHOOL". The Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston, Tas. : 1835 - 1880). Launceston, Tas.: National Library of Australia. 27 January 1838. p. 13. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- "Mail coach". Powerhouse Museum. 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mail coaches. |

- History of the Post Bath Postal Museum

- The Mail, by Anne Woodley

- Miscellaneous Essays - The English Mail Coach, by Thomas de Quincey. Authorama - Public Domain Books

- Mail Coaches British Postal Museum & Archive

- Mail Coach Routes - Direct from Dublin from Leigh's New Pocket Road-book of Ireland, 1835.