Machine translation

Machine translation, sometimes referred to by the abbreviation MT[1] (not to be confused with computer-aided translation, machine-aided human translation or interactive translation), is a sub-field of computational linguistics that investigates the use of software to translate text or speech from one language to another.

| Part of a series on |

| Translation |

|---|

|

| Types |

| Theory |

| Technologies |

| Localization |

|

| Institutional |

|

| Related topics |

|

On a basic level, MT performs mechanical substitution of words in one language for words in another, but that alone rarely produces a good translation because recognition of whole phrases and their closest counterparts in the target language is needed. Not all words in one language have equivalent words in another language, and many words have more than one meaning.

Solving this problem with corpus statistical and neural techniques is a rapidly-growing field that is leading to better translations, handling differences in linguistic typology, translation of idioms, and the isolation of anomalies.[2]

Current machine translation software often allows for customization by domain or profession (such as weather reports), improving output by limiting the scope of allowable substitutions. This technique is particularly effective in domains where formal or formulaic language is used. It follows that machine translation of government and legal documents more readily produces usable output than conversation or less standardised text.

Improved output quality can also be achieved by human intervention: for example, some systems are able to translate more accurately if the user has unambiguously identified which words in the text are proper names. With the assistance of these techniques, MT has proven useful as a tool to assist human translators and, in a very limited number of cases, can even produce output that can be used as is (e.g., weather reports).

The progress and potential of machine translation have been much debated through its history. Since the 1950s, a number of scholars, first and most notably Yehoshua Bar-Hillel,[3] have questioned the possibility of achieving fully automatic machine translation of high quality.[4]

History

Origins

The origins of machine translation can be traced back to the work of Al-Kindi, a 9th-century Arabic cryptographer who developed techniques for systemic language translation, including cryptanalysis, frequency analysis, and probability and statistics, which are used in modern machine translation.[5] The idea of machine translation later appeared in the 17th century. In 1629, René Descartes proposed a universal language, with equivalent ideas in different tongues sharing one symbol.[6][7]

The idea of using digital computers for translation of natural languages was proposed as early as 1946 by England's A. D. Booth and Warren Weaver at Rockefeller Foundation at the same time. "The memorandum written by Warren Weaver in 1949 is perhaps the single most influential publication in the earliest days of machine translation."[8][9] Others followed. A demonstration was made in 1954 on the APEXC machine at Birkbeck College (University of London) of a rudimentary translation of English into French. Several papers on the topic were published at the time, and even articles in popular journals (for example an article by Cleave and Zacharov in the September 1955 issue of Wireless World). A similar application, also pioneered at Birkbeck College at the time, was reading and composing Braille texts by computer.

1950s

The first researcher in the field, Yehoshua Bar-Hillel, began his research at MIT (1951). A Georgetown University MT research team followed (1951) with a public demonstration of its Georgetown-IBM experiment system in 1954. MT research programs popped up in Japan[10][11] and Russia (1955), and the first MT conference was held in London (1956).[12][13]

David G. Hays "wrote about computer-assisted language processing as early as 1957" and "was project leader on computational linguistics at Rand from 1955 to 1968."[14]

1960-1975

Researchers continued to join the field as the Association for Machine Translation and Computational Linguistics was formed in the U.S. (1962) and the National Academy of Sciences formed the Automatic Language Processing Advisory Committee (ALPAC) to study MT (1964). Real progress was much slower, however, and after the ALPAC report (1966), which found that the ten-year-long research had failed to fulfill expectations, funding was greatly reduced.[15] According to a 1972 report by the Director of Defense Research and Engineering (DDR&E), the feasibility of large-scale MT was reestablished by the success of the Logos MT system in translating military manuals into Vietnamese during that conflict.

The French Textile Institute also used MT to translate abstracts from and into French, English, German and Spanish (1970); Brigham Young University started a project to translate Mormon texts by automated translation (1971).

1975 and beyond

SYSTRAN, which "pioneered the field under contracts from the U. S. government"[1] in the 1960s, was used by Xerox to translate technical manuals (1978). Beginning in the late 1980s, as computational power increased and became less expensive, more interest was shown in statistical models for machine translation. MT became more popular after the advent of computers.[16] SYSTRAN's first implementation system was implemented in 1988 by the online service of the French Postal Service called Minitel.[17] Various MT companies were also launched, including Trados (1984), which was the first to develop and market translation memory technology (1989). The first commercial MT system for Russian / English / German-Ukrainian was developed at Kharkov State University (1991).

By 1998, "for as little as $29.95" one could "buy a program for translating in one direction between English and a major European language of your choice" to run on a PC.[1]

MT on the web started with SYSTRAN offering free translation of small texts (1996) and then providing this via AltaVista Babelfish,[1] which racked up 500,000 requests a day (1997).[18] The second free translation service on the web was Lernout & Hauspie's GlobaLink.[1] Atlantic Magazine wrote in 1998 that "Systran's Babelfish and GlobaLink's Comprende" handled "Don't bank on it" with a "competent performance."[19]

Franz Josef Och (the future head of Translation Development AT Google) won DARPA's speed MT competition (2003).[20] More innovations during this time included MOSES, the open-source statistical MT engine (2007), a text/SMS translation service for mobiles in Japan (2008), and a mobile phone with built-in speech-to-speech translation functionality for English, Japanese and Chinese (2009). Recently, Google announced that Google Translate translates roughly enough text to fill 1 million books in one day (2012).

Translation process

The human translation process may be described as:

- Decoding the meaning of the source text; and

- Re-encoding this meaning in the target language.

Behind this ostensibly simple procedure lies a complex cognitive operation. To decode the meaning of the source text in its entirety, the translator must interpret and analyse all the features of the text, a process that requires in-depth knowledge of the grammar, semantics, syntax, idioms, etc., of the source language, as well as the culture of its speakers. The translator needs the same in-depth knowledge to re-encode the meaning in the target language.[21]

Therein lies the challenge in machine translation: how to program a computer that will "understand" a text as a person does, and that will "create" a new text in the target language that sounds as if it has been written by a person. Unless aided by a 'knowledge base' MT provides only a general, though imperfect, approximation of the original text, getting the "gist" of it (a process called "gisting"). This is sufficient for many purposes, including making best use of the finite and expensive time of a human translator, reserved for those cases in which total accuracy is indispensable.

Approaches

Machine translation can use a method based on linguistic rules, which means that words will be translated in a linguistic way – the most suitable (orally speaking) words of the target language will replace the ones in the source language.

It is often argued that the success of machine translation requires the problem of natural language understanding to be solved first.[22]

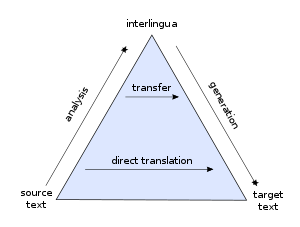

Generally, rule-based methods parse a text, usually creating an intermediary, symbolic representation, from which the text in the target language is generated. According to the nature of the intermediary representation, an approach is described as interlingual machine translation or transfer-based machine translation. These methods require extensive lexicons with morphological, syntactic, and semantic information, and large sets of rules.

Given enough data, machine translation programs often work well enough for a native speaker of one language to get the approximate meaning of what is written by the other native speaker. The difficulty is getting enough data of the right kind to support the particular method. For example, the large multilingual corpus of data needed for statistical methods to work is not necessary for the grammar-based methods. But then, the grammar methods need a skilled linguist to carefully design the grammar that they use.

To translate between closely related languages, the technique referred to as rule-based machine translation may be used.

Rule-based

The rule-based machine translation paradigm includes transfer-based machine translation, interlingual machine translation and dictionary-based machine translation paradigms. This type of translation is used mostly in the creation of dictionaries and grammar programs. Unlike other methods, RBMT involves more information about the linguistics of the source and target languages, using the morphological and syntactic rules and semantic analysis of both languages. The basic approach involves linking the structure of the input sentence with the structure of the output sentence using a parser and an analyzer for the source language, a generator for the target language, and a transfer lexicon for the actual translation. RBMT's biggest downfall is that everything must be made explicit: orthographical variation and erroneous input must be made part of the source language analyser in order to cope with it, and lexical selection rules must be written for all instances of ambiguity. Adapting to new domains in itself is not that hard, as the core grammar is the same across domains, and the domain-specific adjustment is limited to lexical selection adjustment.

Transfer-based machine translation

Transfer-based machine translation is similar to interlingual machine translation in that it creates a translation from an intermediate representation that simulates the meaning of the original sentence. Unlike interlingual MT, it depends partially on the language pair involved in the translation.

Interlingual

Interlingual machine translation is one instance of rule-based machine-translation approaches. In this approach, the source language, i.e. the text to be translated, is transformed into an interlingual language, i.e. a "language neutral" representation that is independent of any language. The target language is then generated out of the interlingua. One of the major advantages of this system is that the interlingua becomes more valuable as the number of target languages it can be turned into increases. However, the only interlingual machine translation system that has been made operational at the commercial level is the KANT system (Nyberg and Mitamura, 1992), which is designed to translate Caterpillar Technical English (CTE) into other languages.

Dictionary-based

Machine translation can use a method based on dictionary entries, which means that the words will be translated as they are by a dictionary.

Statistical

Statistical machine translation tries to generate translations using statistical methods based on bilingual text corpora, such as the Canadian Hansard corpus, the English-French record of the Canadian parliament and EUROPARL, the record of the European Parliament. Where such corpora are available, good results can be achieved translating similar texts, but such corpora are still rare for many language pairs. The first statistical machine translation software was CANDIDE from IBM. Google used SYSTRAN for several years, but switched to a statistical translation method in October 2007.[23] In 2005, Google improved its internal translation capabilities by using approximately 200 billion words from United Nations materials to train their system; translation accuracy improved.[24] Google Translate and similar statistical translation programs work by detecting patterns in hundreds of millions of documents that have previously been translated by humans and making intelligent guesses based on the findings. Generally, the more human-translated documents available in a given language, the more likely it is that the translation will be of good quality.[25] Newer approaches into Statistical Machine translation such as METIS II and PRESEMT use minimal corpus size and instead focus on derivation of syntactic structure through pattern recognition. With further development, this may allow statistical machine translation to operate off of a monolingual text corpus.[26] SMT's biggest downfall includes it being dependent upon huge amounts of parallel texts, its problems with morphology-rich languages (especially with translating into such languages), and its inability to correct singleton errors.

Example-based

Example-based machine translation (EBMT) approach was proposed by Makoto Nagao in 1984.[27][28] Example-based machine translation is based on the idea of analogy. In this approach, the corpus that is used is one that contains texts that have already been translated. Given a sentence that is to be translated, sentences from this corpus are selected that contain similar sub-sentential components.[29] The similar sentences are then used to translate the sub-sentential components of the original sentence into the target language, and these phrases are put together to form a complete translation.

Hybrid MT

Hybrid machine translation (HMT) leverages the strengths of statistical and rule-based translation methodologies.[30] Several MT organizations claim a hybrid approach that uses both rules and statistics. The approaches differ in a number of ways:

- Rules post-processed by statistics: Translations are performed using a rules based engine. Statistics are then used in an attempt to adjust/correct the output from the rules engine.

- Statistics guided by rules: Rules are used to pre-process data in an attempt to better guide the statistical engine. Rules are also used to post-process the statistical output to perform functions such as normalization. This approach has a lot more power, flexibility and control when translating. It also provides extensive control over the way in which the content is processed during both pre-translation (e.g. markup of content and non-translatable terms) and post-translation (e.g. post translation corrections and adjustments).

More recently, with the advent of Neural MT, a new version of hybrid machine translation is emerging that combines the benefits of rules, statistical and neural machine translation. The approach allows benefitting from pre- and post-processing in a rule guided workflow as well as benefitting from NMT and SMT. The downside is the inherent complexity which makes the approach suitable only for specific use cases. One of the proponents of this approach for complex use cases is Omniscien Technologies.

Neural MT

A deep learning based approach to MT, neural machine translation has made rapid progress in recent years, and Google has announced its translation services are now using this technology in preference to its previous statistical methods.[31] Microsoft team reached human parity on WMT-2017 in 2018 and this was a historical milestone.[32]

Major issues

Disambiguation

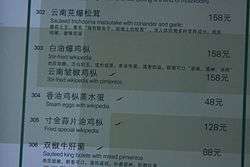

Word-sense disambiguation concerns finding a suitable translation when a word can have more than one meaning. The problem was first raised in the 1950s by Yehoshua Bar-Hillel.[33] He pointed out that without a "universal encyclopedia", a machine would never be able to distinguish between the two meanings of a word.[34] Today there are numerous approaches designed to overcome this problem. They can be approximately divided into "shallow" approaches and "deep" approaches.

Shallow approaches assume no knowledge of the text. They simply apply statistical methods to the words surrounding the ambiguous word. Deep approaches presume a comprehensive knowledge of the word. So far, shallow approaches have been more successful.[35]

Claude Piron, a long-time translator for the United Nations and the World Health Organization, wrote that machine translation, at its best, automates the easier part of a translator's job; the harder and more time-consuming part usually involves doing extensive research to resolve ambiguities in the source text, which the grammatical and lexical exigencies of the target language require to be resolved:

- Why does a translator need a whole workday to translate five pages, and not an hour or two? ..... About 90% of an average text corresponds to these simple conditions. But unfortunately, there's the other 10%. It's that part that requires six [more] hours of work. There are ambiguities one has to resolve. For instance, the author of the source text, an Australian physician, cited the example of an epidemic which was declared during World War II in a "Japanese prisoner of war camp". Was he talking about an American camp with Japanese prisoners or a Japanese camp with American prisoners? The English has two senses. It's necessary therefore to do research, maybe to the extent of a phone call to Australia.[36]

The ideal deep approach would require the translation software to do all the research necessary for this kind of disambiguation on its own; but this would require a higher degree of AI than has yet been attained. A shallow approach which simply guessed at the sense of the ambiguous English phrase that Piron mentions (based, perhaps, on which kind of prisoner-of-war camp is more often mentioned in a given corpus) would have a reasonable chance of guessing wrong fairly often. A shallow approach that involves "ask the user about each ambiguity" would, by Piron's estimate, only automate about 25% of a professional translator's job, leaving the harder 75% still to be done by a human.

Non-standard speech

One of the major pitfalls of MT is its inability to translate non-standard language with the same accuracy as standard language. Heuristic or statistical based MT takes input from various sources in standard form of a language. Rule-based translation, by nature, does not include common non-standard usages. This causes errors in translation from a vernacular source or into colloquial language. Limitations on translation from casual speech present issues in the use of machine translation in mobile devices.

Named entities

In information extraction, named entities, in a narrow sense, refer to concrete or abstract entities in the real world such as people, organizations, companies, and places that have a proper name: George Washington, Chicago, Microsoft. It also refers to expressions of time, space and quantity such as 1 July 2011, $500.

In the sentence "Smith is the president of Fabrionix" both Smith and Fabrionix are named entities, and can be further qualified via first name or other information; "president" is not, since Smith could have earlier held another position at Fabrionix, e.g. Vice President. The term rigid designator is what defines these usages for analysis in statistical machine translation.

Named entities must first be identified in the text; if not, they may be erroneously translated as common nouns, which would most likely not affect the BLEU rating of the translation but would change the text's human readability.[37] They may be omitted from the output translation, which would also have implications for the text's readability and message.

Transliteration includes finding the letters in the target language that most closely correspond to the name in the source language. This, however, has been cited as sometimes worsening the quality of translation.[38] For "Southern California" the first word should be translated directly, while the second word should be transliterated. Machines often transliterate both because they treated them as one entity. Words like these are hard for machine translators, even those with a transliteration component, to process.

Use of a "do-not-translate" list, which has the same end goal – transliteration as opposed to translation.[39] still relies on correct identification of named entities.

A third approach is a class-based model. Named entities are replaced with a token to represent their "class;" "Ted" and "Erica" would both be replaced with "person" class token. Then the statistical distribution and use of person names in general can be analyzed instead of looking at the distributions of "Ted" and "Erica" individually, so that the probability of a given name in a specific language will not affect the assigned probability of a translation. A study by Stanford on improving this area of translation gives the examples that different probabilities will be assigned to "David is going for a walk" and "Ankit is going for a walk" for English as a target language due to the different number of occurrences for each name in the training data. A frustrating outcome of the same study by Stanford (and other attempts to improve named recognition translation) is that many times, a decrease in the BLEU scores for translation will result from the inclusion of methods for named entity translation.[39]

Somewhat related are the phrases "drinking tea with milk" vs. "drinking tea with Molly."

Translation from multiparallel sources

Some work has been done in the utilization of multiparallel corpora, that is a body of text that has been translated into 3 or more languages. Using these methods, a text that has been translated into 2 or more languages may be utilized in combination to provide a more accurate translation into a third language compared with if just one of those source languages were used alone.[40][41][42]

Ontologies in MT

An ontology is a formal representation of knowledge which includes the concepts (such as objects, processes etc.) in a domain and some relations between them. If the stored information is of linguistic nature, one can speak of a lexicon.[43] In NLP, ontologies can be used as a source of knowledge for machine translation systems. With access to a large knowledge base, systems can be enabled to resolve many (especially lexical) ambiguities on their own. In the following classic examples, as humans, we are able to interpret the prepositional phrase according to the context because we use our world knowledge, stored in our lexicons:

"I saw a man/star/molecule with a microscope/telescope/binoculars."[43]

A machine translation system initially would not be able to differentiate between the meanings because syntax does not change. With a large enough ontology as a source of knowledge however, the possible interpretations of ambiguous words in a specific context can be reduced. Other areas of usage for ontologies within NLP include information retrieval, information extraction and text summarization.[43]

Building ontologies

The ontology generated for the PANGLOSS knowledge-based machine translation system in 1993 may serve as an example of how an ontology for NLP purposes can be compiled:[44]

- A large-scale ontology is necessary to help parsing in the active modules of the machine translation system.

- In the PANGLOSS example, about 50,000 nodes were intended to be subsumed under the smaller, manually-built upper (abstract) region of the ontology. Because of its size, it had to be created automatically.

- The goal was to merge the two resources LDOCE online and WordNet to combine the benefits of both: concise definitions from Longman, and semantic relations allowing for semi-automatic taxonomization to the ontology from WordNet.

- A definition match algorithm was created to automatically merge the correct meanings of ambiguous words between the two online resources, based on the words that the definitions of those meanings have in common in LDOCE and WordNet. Using a similarity matrix, the algorithm delivered matches between meanings including a confidence factor. This algorithm alone, however, did not match all meanings correctly on its own.

- A second hierarchy match algorithm was therefore created which uses the taxonomic hierarchies found in WordNet (deep hierarchies) and partially in LDOCE (flat hierarchies). This works by first matching unambiguous meanings, then limiting the search space to only the respective ancestors and descendants of those matched meanings. Thus, the algorithm matched locally unambiguous meanings (for instance, while the word seal as such is ambiguous, there is only one meaning of "seal" in the animal subhierarchy).

- Both algorithms complemented each other and helped constructing a large-scale ontology for the machine translation system. The WordNet hierarchies, coupled with the matching definitions of LDOCE, were subordinated to the ontology's upper region. As a result, the PANGLOSS MT system was able to make use of this knowledge base, mainly in its generation element.

Applications

While no system provides the holy grail of fully automatic high-quality machine translation of unrestricted text, many fully automated systems produce reasonable output.[45][46][47] The quality of machine translation is substantially improved if the domain is restricted and controlled.[48]

Despite their inherent limitations, MT programs are used around the world. Probably the largest institutional user is the European Commission. The MOLTO project, for example, coordinated by the University of Gothenburg, received more than 2.375 million euros project support from the EU to create a reliable translation tool that covers a majority of the EU languages.[49] The further development of MT systems comes at a time when budget cuts in human translation may increase the EU's dependency on reliable MT programs.[50] The European Commission contributed 3.072 million euros (via its ISA programme) for the creation of MT@EC, a statistical machine translation program tailored to the administrative needs of the EU, to replace a previous rule-based machine translation system.[51]

In 2005, Google claimed that promising results were obtained using a proprietary statistical machine translation engine.[52] The statistical translation engine used in the Google language tools for Arabic <-> English and Chinese <-> English had an overall score of 0.4281 over the runner-up IBM's BLEU-4 score of 0.3954 (Summer 2006) in tests conducted by the National Institute for Standards and Technology.[53][54][55]

With the recent focus on terrorism, the military sources in the United States have been investing significant amounts of money in natural language engineering. In-Q-Tel[56] (a venture capital fund, largely funded by the US Intelligence Community, to stimulate new technologies through private sector entrepreneurs) brought up companies like Language Weaver. Currently the military community is interested in translation and processing of languages like Arabic, Pashto, and Dari. Within these languages, the focus is on key phrases and quick communication between military members and civilians through the use of mobile phone apps.[57] The Information Processing Technology Office in DARPA hosts programs like TIDES and Babylon translator. US Air Force has awarded a $1 million contract to develop a language translation technology.[58]

The notable rise of social networking on the web in recent years has created yet another niche for the application of machine translation software – in utilities such as Facebook, or instant messaging clients such as Skype, GoogleTalk, MSN Messenger, etc. – allowing users speaking different languages to communicate with each other. Machine translation applications have also been released for most mobile devices, including mobile telephones, pocket PCs, PDAs, etc. Due to their portability, such instruments have come to be designated as mobile translation tools enabling mobile business networking between partners speaking different languages, or facilitating both foreign language learning and unaccompanied traveling to foreign countries without the need of the intermediation of a human translator.

Despite being labelled as an unworthy competitor to human translation in 1966 by the Automated Language Processing Advisory Committee put together by the United States government,[59] the quality of machine translation has now been improved to such levels that its application in online collaboration and in the medical field are being investigated. The application of this technology in medical settings where human translators are absent is another topic of research, but difficulties arise due to the importance of accurate translations in medical diagnoses.[60]

Evaluation

There are many factors that affect how machine translation systems are evaluated. These factors include the intended use of the translation, the nature of the machine translation software, and the nature of the translation process.

Different programs may work well for different purposes. For example, statistical machine translation (SMT) typically outperforms example-based machine translation (EBMT), but researchers found that when evaluating English to French translation, EBMT performs better.[61] The same concept applies for technical documents, which can be more easily translated by SMT because of their formal language.

In certain applications, however, e.g., product descriptions written in a controlled language, a dictionary-based machine-translation system has produced satisfactory translations that require no human intervention save for quality inspection.[62]

There are various means for evaluating the output quality of machine translation systems. The oldest is the use of human judges[63] to assess a translation's quality. Even though human evaluation is time-consuming, it is still the most reliable method to compare different systems such as rule-based and statistical systems.[64] Automated means of evaluation include BLEU, NIST, METEOR, and LEPOR.[65]

Relying exclusively on unedited machine translation ignores the fact that communication in human language is context-embedded and that it takes a person to comprehend the context of the original text with a reasonable degree of probability. It is certainly true that even purely human-generated translations are prone to error. Therefore, to ensure that a machine-generated translation will be useful to a human being and that publishable-quality translation is achieved, such translations must be reviewed and edited by a human.[66] The late Claude Piron wrote that machine translation, at its best, automates the easier part of a translator's job; the harder and more time-consuming part usually involves doing extensive research to resolve ambiguities in the source text, which the grammatical and lexical exigencies of the target language require to be resolved. Such research is a necessary prelude to the pre-editing necessary in order to provide input for machine-translation software such that the output will not be meaningless.[67]

In addition to disambiguation problems, decreased accuracy can occur due to varying levels of training data for machine translating programs. Both example-based and statistical machine translation rely on a vast array of real example sentences as a base for translation, and when too many or too few sentences are analyzed accuracy is jeopardized. Researchers found that when a program is trained on 203,529 sentence pairings, accuracy actually decreases.[61] The optimal level of training data seems to be just over 100,000 sentences, possibly because as training data increases, the number of possible sentences increases, making it harder to find an exact translation match.

Using machine translation as a teaching tool

Although there have been concerns about machine translation's accuracy, Dr. Ana Nino of the University of Manchester has researched some of the advantages in utilizing machine translation in the classroom. One such pedagogical method is called using "MT as a Bad Model."[68] MT as a Bad Model forces the language learner to identify inconsistencies or incorrect aspects of a translation; in turn, the individual will (hopefully) possess a better grasp of the language. Dr. Nino cites that this teaching tool was implemented in the late 1980s. At the end of various semesters, Dr. Nino was able to obtain survey results from students who had used MT as a Bad Model (as well as other models.) Overwhelmingly, students felt that they had observed improved comprehension, lexical retrieval, and increased confidence in their target language.[68]

Machine translation and signed languages

In the early 2000s, options for machine translation between spoken and signed languages were severely limited. It was a common belief that deaf individuals could use traditional translators. However, stress, intonation, pitch, and timing are conveyed much differently in spoken languages compared to signed languages. Therefore, a deaf individual may misinterpret or become confused about the meaning of written text that is based on a spoken language.[69]

Researchers Zhao, et al. (2000), developed a prototype called TEAM (translation from English to ASL by machine) that completed English to American Sign Language (ASL) translations. The program would first analyze the syntactic, grammatical, and morphological aspects of the English text. Following this step, the program accessed a sign synthesizer, which acted as a dictionary for ASL. This synthesizer housed the process one must follow to complete ASL signs, as well as the meanings of these signs. Once the entire text is analyzed and the signs necessary to complete the translation are located in the synthesizer, a computer generated human appeared and would use ASL to sign the English text to the user.[69]

Copyright

Only works that are original are subject to copyright protection, so some scholars claim that machine translation results are not entitled to copyright protection because MT does not involve creativity.[70] The copyright at issue is for a derivative work; the author of the original work in the original language does not lose his rights when a work is translated: a translator must have permission to publish a translation.

See also

- AI-complete

- Cache language model

- Comparison of machine translation applications

- Comparison of different machine translation approaches

- Computational linguistics

- Computer-assisted translation and Translation memory

- Controlled language in machine translation

- Controlled natural language

- Foreign language writing aid

- Fuzzy matching

- History of machine translation

- Human language technology

- Humour in translation ("howlers")

- Language and Communication Technologies

- Language barrier

- List of emerging technologies

- List of research laboratories for machine translation

- Mobile translation

- Neural machine translation

- OpenLogos

- Phraselator

- Postediting

- Pseudo-translation

- Round-trip translation

- Statistical machine translation

- Translation

- Translation memory

- ULTRA (machine translation system)

- Universal Networking Language

- Universal translator

Notes

- Stephen Budiansky (December 1998). "Lost in Translation". Atlantic Magazine. pp. 81–84.

- Albat, Thomas Fritz. "Systems and Methods for Automatically Estimating a Translation Time." US Patent 0185235, 19 July 2012.

- Yehoshua Bar-Hillel (1964). Language and Information: Selected Essays on Their Theory and Application. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. pp. 174–179.

- Madsen, Mathias Winther (2009). The Limits of Machine Translation. M.A. thesis, University of Copenhagen. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- DuPont, Quinn (January 2018). "The Cryptological Origins of Machine Translation: From al-Kindi to Weaver". Amodern (8).

- James Knowlson (1975). Universal language schemes in England and France, 1600-1800. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-5296-4.

- [https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Machine_translation&diff=971626168&oldid=971623219 Japanese 1993 translation]

- J. Hutchins. "Warren Weaver and the launching of MT" (PDF). Semantic Scholar.

- "Warren Weaver, American mathematician". 13 July 2020.

- 上野, 俊夫 (13 August 1986). パーソナルコンピュータによる機械翻訳プログラムの制作 (in Japanese). Tokyo: (株)ラッセル社. p. 16. ISBN 494762700X.

わが国では1956年、当時の電気試験所が英和翻訳専用機「ヤマト」を実験している。この機械は1962年頃には中学1年の教科書で90点以上の能力に達したと報告されている。(translation (assisted by Google translate): In 1959 Japan, the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology(AIST) tested the proper English-Japanese translation machine Yamato, which reported in 1964 as that reached the power level over the score of 90-point on the textbook of 1st grade of junior hi-school.)

- "機械翻訳専用機「やまと」-コンピュータ博物館".

- Nye, Mary Jo (2016). "Speaking in Tongues: Science's centuries-long hunt for a common language". Distillations. 2 (1): 40–43. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- Gordin, Michael D. (2015). Scientific Babel: How Science Was Done Before and After Global English. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226000299.

- Wolfgang Saxon (28 July 1995). "David G. Hays, 66, a Developer Of Language Study by Computer". The New York Times.

wrote about computer-assisted language processing as early as 1957.. was project leader on computational linguistics at Rand from 1955 to 1968.

- 上野, 俊夫 (13 August 1986). パーソナルコンピュータによる機械翻訳プログラムの制作 (in Japanese). Tokyo: (株)ラッセル社. p. 16. ISBN 494762700X.

- Schank, Roger C. (2014). Conceptual Information Processing. New York: Elsevier. p. 5. ISBN 9781483258799.

- Farwell, David; Gerber, Laurie; Hovy, Eduard (29 June 2003). Machine Translation and the Information Soup: Third Conference of the Association for Machine Translation in the Americas, AMTA'98, Langhorne, PA, USA, October 28–31, 1998 Proceedings. Berlin: Springer. p. 276. ISBN 3540652590.

- Barron, Brenda (18 November 2019). "Babel Fish: What Happened To The Original Translation Application?: We Investigate". Digital.com. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- and gave other examples too

- Chan, Sin-Wai (2015). Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Technology. Oxon: Routledge. p. 385. ISBN 9780415524841.

- Bai Liping, "Similarity and difference in Translation." Taken from Similarity and Difference in Translation: Proceedings of the International Conference on Similarity and Translation, pg. 339. Eds. Stefano Arduini and Robert Hodgson. 2nd ed. Rome: Edizioni di storia e letteratura, 2007. ISBN 9788884983749

- John Lehrberger (1988). Machine Translation: Linguistic Characteristics of MT Systems and General Methodology of Evaluation. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 90-272-3124-9.

- Chitu, Alex (22 October 2007). "Google Switches to Its Own Translation System". Googlesystem.blogspot.com. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "Google Translator: The Universal Language". Blog.outer-court.com. 25 January 2007. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "Inside Google Translate – Google Translate".

- http://www.mt-archive.info/10/HyTra-2013-Tambouratzis.pdf

- Nagao, M. 1981. A Framework of a Mechanical Translation between Japanese and English by Analogy Principle, in Artificial and Human Intelligence, A. Elithorn and R. Banerji (eds.) North- Holland, pp. 173–180, 1984.

- "the Association for Computational Linguistics – 2003 ACL Lifetime Achievement Award". Association for Computational Linguistics. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- "Kitt.cl.uzh.ch [CL Wiki]" (PDF).

- Adam Boretz (2 March 2009). "Boretz, Adam, "AppTek Launches Hybrid Machine Translation Software" SpeechTechMag.com (posted 2 MAR 2009)". Speechtechmag.com. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "Google's neural network learns to translate languages it hasn't been trained on".

- https://blogs.microsoft.com/ai/chinese-to-english-translator-milestone/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Milestones in machine translation – No.6: Bar-Hillel and the nonfeasibility of FAHQT Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine by John Hutchins

- Bar-Hillel (1960), "Automatic Translation of Languages". Available online at http://www.mt-archive.info/Bar-Hillel-1960.pdf

- Hybrid approaches to machine translation. Costa-jussà, Marta R.,, Rapp, Reinhard,, Lambert, Patrik,, Eberle, Kurt,, Banchs, Rafael E.,, Babych, Bogdan. Switzerland. ISBN 9783319213101. OCLC 953581497.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Claude Piron, Le défi des langues (The Language Challenge), Paris, L'Harmattan, 1994.

- http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~ar283/eacl03/workshops03/W03-w1_eacl03babych.local.pdf

- Hermajakob, U., Knight, K., & Hal, D. (2008). Name Translation in Statistical Machine Translation Learning When to Transliterate. Association for Computational Linguistics. 389–397.

- http://nlp.stanford.edu/courses/cs224n/2010/reports/singla-nirajuec.pdf

- https://dowobeha.github.io/papers/amta08.pdf

- http://homepages.inf.ed.ac.uk/mlap/Papers/acl07.pdf

- https://www.jair.org/media/3540/live-3540-6293-jair.pdf

- Vossen, Piek: Ontologies. In: Mitkov, Ruslan (ed.) (2003): Handbook of Computational Linguistics, Chapter 25. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Knight, Kevin (1994). "Building a large ontology for machine translation (1993)". arXiv:cmp-lg/9407029. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Melby, Alan. The Possibility of Language (Amsterdam:Benjamins, 1995, 27–41). Benjamins.com. 1995. ISBN 9789027216144. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- Adam (14 February 2006). "Wooten, Adam. "A Simple Model Outlining Translation Technology" T&I Business (February 14, 2006)". Tandibusiness.blogspot.com. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "Appendix III of 'The present status of automatic translation of languages', Advances in Computers, vol.1 (1960), p.158-163. Reprinted in Y.Bar-Hillel: Language and information (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1964), p.174-179" (PDF). Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "Human quality machine translation solution by Ta with you" (in Spanish). Tauyou.com. 15 April 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "molto-project.eu". molto-project.eu. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg, Germany (13 September 2013). "Google Translate Has Ambitious Goals for Machine Translation". SPIEGEL ONLINE.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Machine Translation Service". 5 August 2011.

- Google Blog: The machines do the translating (by Franz Och)

- "Geer, David, "Statistical Translation Gains Respect", pp. 18 – 21, IEEE Computer, October 2005". Ieeexplore.ieee.org. 27 September 2011. doi:10.1109/MC.2005.353. S2CID 7088166. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ratliff, Evan (4 January 2009). "Ratcliff, Evan "Me Translate Pretty One Day", Wired December 2006". Wired. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ""NIST 2006 Machine Translation Evaluation Official Results", November 1, 2006". Itl.nist.gov. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "In-Q-Tel". In-Q-Tel. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- Gallafent, Alex (26 April 2011). "Machine Translation for the Military". PRI's the World. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- Jackson, William (9 September 2003). "GCN – Air force wants to build a universal translator". Gcn.com. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- http://www.nap.edu/html/alpac_lm/ARC000005.pdf

- "Using machine translation in clinical practice".

- Way, Andy; Nano Gough (20 September 2005). "Comparing Example-Based and Statistical Machine Translation". Natural Language Engineering. 11 (3): 295–309. doi:10.1017/S1351324905003888.

- Muegge (2006), "Fully Automatic High Quality Machine Translation of Restricted Text: A Case Study," in Translating and the computer 28. Proceedings of the twenty-eighth international conference on translating and the computer, 16–17 November 2006, London, London: Aslib. ISBN 978-0-85142-483-5.

- "Comparison of MT systems by human evaluation, May 2008". Morphologic.hu. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- Anderson, D.D. (1995). Machine translation as a tool in second language learning. CALICO Journal. 13(1). 68–96.

- Han et al. (2012), "LEPOR: A Robust Evaluation Metric for Machine Translation with Augmented Factors," in Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING 2012): Posters, pages 441–450, Mumbai, India.

- J.M. Cohen observes (p.14): "Scientific translation is the aim of an age that would reduce all activities to techniques. It is impossible however to imagine a literary-translation machine less complex than the human brain itself, with all its knowledge, reading, and discrimination."

- See the annually performed NIST tests since 2001 and Bilingual Evaluation Understudy

- Nino, Ana. "Machine Translation in Foreign Language Learning: Language Learners' and Tutors' Perceptions of Its Advantages and Disadvantages" ReCALL: the Journal of EUROCALL 21.2 (May 2009) 241–258.

- Zhao, L., Kipper, K., Schuler, W., Vogler, C., & Palmer, M. (2000). A Machine Translation System from English to American Sign Language. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 1934: 54–67.

- "Machine Translation: No Copyright On The Result?". SEO Translator, citing Zimbabwe Independent. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

Further reading

- Cohen, J. M. (1986), "Translation", Encyclopedia Americana, 27, pp. 12–15

- Hutchins, W. John; Somers, Harold L. (1992). An Introduction to Machine Translation. London: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-362830-X.

- Lewis-Kraus, Gideon, "Tower of Babble", New York Times Magazine, 7 June 2015, pp. 48–52.

External links

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Topic:Computational linguistics |

- The Advantages and Disadvantages of Machine Translation

- Why Google will never replace a translation agency

- International Association for Machine Translation (IAMT)

- Machine Translation Archive by John Hutchins. An electronic repository (and bibliography) of articles, books and papers in the field of machine translation and computer-based translation technology

- Machine translation (computer-based translation) – Publications by John Hutchins (includes PDFs of several books on machine translation)

- Machine Translation and Minority Languages

- John Hutchins 1999