Moesia

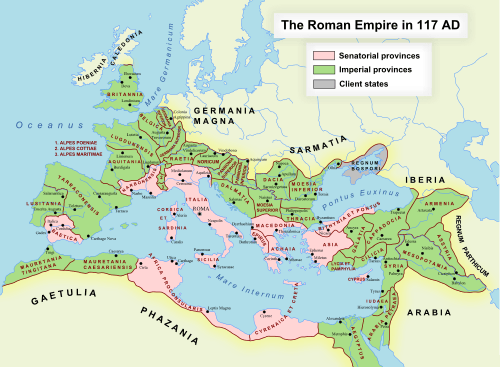

Moesia (/ˈmiːʃə, -siə, -ʒə/;[1][2] Latin: Moesia, Greek: Μοισία, romanized: Moisía)[3] was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River. It included most of the territory of modern-day Central Serbia, Kosovo and the northern parts of the modern North Macedonia (Moesia Superior), Northern Bulgaria, Romanian Dobrudja and Southern Ukraine (Moesia Inferior).

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Geography

In ancient geographical sources, Moesia was bounded to the south by the Haemus (Balkans) and Scardus (Šar) mountains, to the west by the Drinus (Drina) river, on the north by the Donaris (Danube) and on the east by the Euxine (Black Sea).[4]

History

The region was inhabited chiefly by Thracians, Dacians (Thraco-Dacians), Illyrian and Thraco-Illyrian peoples. The name of the region comes from Moesi, Thraco-Dacian peoples who lived there before the Roman conquest.

Parts of Moesia belonged to the polity of Burebista, a Getae king who established his rule over a large part of the northern Balkans between 82 BC and 44 BC. He led plunder and conquest raids across Central and Southeastern Europe, subjugating most of the neighbouring tribes. After his assassination in an inside plot, the empire was divided into several smaller states.

In 75 BC, C. Scribonius Curio, proconsul of Macedonia, took an army as far as the Danube and gained a victory over the inhabitants, who were finally subdued by M. Licinius Crassus, grandson of the triumvir and later also proconsul of Macedonia during the reign of Augustus c. 29 BC.[4] The region, however, was not organized as a province until the last years of Augustus' reign; in 6 AD, mention is made of its governor, Caecina Severus.[5] As a province, Moesia was under an imperial consular legate (who probably also had control of Achaea and Macedonia).[4]

In 86 AD the Dacian king Duras ordered his troops to attack Roman Moesia. After this attack, the Roman emperor Domitian personally arrived in Moesia and reorganized it in 87 AD into two provinces, divided by the river Cebrus (Ciabrus):[4] to the west Moesia Superior - Upper Moesia, (meaning up river) and to the east Moesia Inferior - Lower Moesia (also called Ripa Thracia), (from the Danube river's mouth and then upstream). Each was governed by an imperial consular legate and a procurator.[4]

The chief towns of Upper Moesia in the Principate were: Singidunum (Belgrade), Viminacium (sometimes called municipium Aelium; modern Kostolac), Remesiana (Bela Palanka), Bononia (Vidin), Ratiaria (Archar) and Skupi (modern Skopje); of Lower Moesia: Oescus (colonia Ulpia, Gigen), Novae (near Svishtov, the chief seat of Theodoric the Great), Nicopolis ad Istrum (Nikup; really near the river Yantra), Marcianopolis (Devnya), Tyras (Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi), Olvia, Odessus (Varna) and Tomis (Constanţa; to which the poet Ovid was banished). The last two were Greek towns which formed a pentapolis with Istros, Mesembria (Nessebar) and Apollonia (Sozopol).[4]

From Moesia, Domitian began planning future campaigns into Dacia and by 87 he started a strong offensive against Dacia, ordering General Cornelius Fuscus to attack. Therefore, in the summer of 87, Fuscus led five or six legions across the Danube. The campaign against the Dacians ended without a decisive outcome, and Decebalus, the Dacian King, had brazenly flouted the terms of the peace (89 AD) which had been agreed on at the war's end.

Emperor Trajan later arrived in Moesia, and he launched his first military campaign into the Dacian Kingdom[6] c. March–May 101, crossing to the northern bank of the Danube River and defeating the Dacian army near Tapae, a mountain pass in the Carpathians (see Second Battle of Tapae). Trajan's troops were mauled in the encounter, however, and he put off further campaigning for the year to heal troops, reinforce, and regroup.[7] During the following winter, King Decebalus launched a counter-attack across the Danube further downstream, but this was repulsed. Trajan's army advanced further into Dacian territory and forced King Decebalus to submit to him a year later.

Trajan returned to Rome in triumph and was granted the title Dacicus. The victory was celebrated by the Tropaeum Traiani. However, Decebalus in 105 undertook an invasion against Roman territory by attempting to stir up some of the tribes north of the river against the empire.[8] Trajan took to the field again and after building with the design of Apollodorus of Damascus his massive bridge over the Danube, he conquered part of Dacia in 106 (see also Second Dacian War).

Sometime around 272, at the Moesian city of Naissus or Nissa (modern Niš in Serbia), future emperor Constantine I was born.

After the abandonment of Roman Dacia to the Goths by Aurelian (270–275) and the transfer of the Roman citizens from the former province to the south of the Danube, the central portion of Moesia took the name of Dacia Aureliana (later divided into Dacia Ripensis[4] and Dacia Mediterranea).

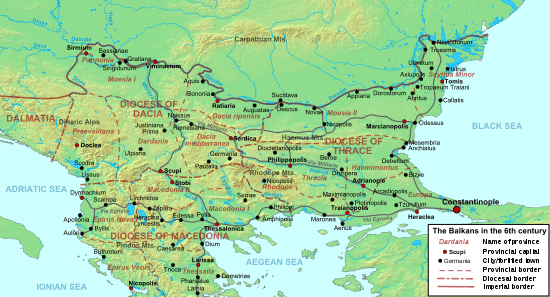

During administrative reforms of Emperor Diocletian (284–305), both of the Moesian provinces were reorganized. Moesia Superior was divided in two, northern part forming the province of Moesia Prima including cities Viminacium and Singidunum, while the southern part was organised as the new province of Dardania with cities Scupi and Ulpiana. At the same time, Moesia Inferior was divided into Moesia Secunda and Scythia Minor. Moesia Secunda's main cities included Marcianopolis (Devnya), Odessus (Varna), Nicopolis (Nikopol), Abrittus (Razgrad), Durostorum (Silistra), Transmarisca (Tutrakan), Sexaginta Prista (Ruse) and Novae (Svishtov), all in Bulgaria today.

As a frontier province, Moesia was strengthened by stations and fortresses erected along the southern bank of the Danube, and a wall was built from Axiopolis to Tomi as a protection against the Scythians and Sarmatians.[4] The garrison of Moesia Secunda included Legio I Italica and Legio XI Claudia, as well as independent infantry units, cavalry units, and river flotillas. The Notitia Dignitatum lists its units and their bases as of the 390s CE. Units in Scythia Minor included Legio I Iovia and Legio II Herculia.

After 238 AD, Moesia was frequently invaded or raided by the Dacian Carpi, and the East Germanic tribe of the Goths, who invaded Moesia in 250. Hard-pressed by the Huns, the Goths again crossed the Danube during the reign of Valens (376) and with his permission settled in Moesia.[4] After they settled, quarrels soon took place, and the Goths under Fritigern defeated Valens in a great battle near Adrianople. These Goths are known as Moeso-Goths, for whom Ulfilas made the Gothic translation of the Bible.[4]

The Slavs allied with the Avars invaded and destroyed much of Moesia in 583–587 in the Avar–Byzantine wars. Moesia was settled by Slavs during the 7th century. Bulgars, arriving from Old Great Bulgaria, conquered Lower Moesia by the end of the 7th century. During the 8th century the Byzantine Empire lost also Upper Moesian territory to the First Bulgarian Empire.

See also

- Diocese of Moesia

- Dacia Aureliana

- List of ancient cities in Thrace and Dacia

- List of Roman governors of Lower Moesia

- List of Roman governors of Upper Moesia

- Inscriptions of Upper Moesia

- Moesogoths

- Margus (city)

References

- Lena Olausson; Catherine Sangster, eds. (2006). Oxford BBC Guide to Pronunciation. Oxford University Press.

- Daniel Jones (2006). Peter Roach; James Hartman; Jane Setter (eds.). Cambridge Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge University Press.

- "C. Suetonius Tranquillus, Vitellius Maximilian Ihm, Ed". perseus.tufts.eud.

- Freese, John Henry (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 643–644.

- Cassius Dio, lv.29

- "Assorted Imperial Battle Descriptions: Battle of Sarmizegetusa (Sarmizegetuza), A.D. 105". De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors.

Because the Dacians represented an obstacle against Roman expansion in the east, in the year 101 the emperor Trajan decided to begin a new campaign against them. The first war began on 25 March 101 and the Roman troops, consisting of four principal legions (X Gemina, XI Claudia, II Traiana Fortis, and XXX Ulpia Victrix), defeated the Dacians.

- "Assorted Imperial Battle Descriptions: Battle of Sarmizegetusa (Sarmizegetuza), A.D. 105". De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors.

Although the Dacians had been defeated, the emperor postponed the final siege for the conquering of Sarmizegetuza because his armies needed reorganization. Trajan imposed on the Dacians very hard peace conditions: Decebalus had to renounce claim to some regions of his kingdom, including Banat, Tara Hategului, Oltenia, and Muntenia in the area southwest of Transylvania. He had also to surrender all the Roman deserters and all his war machines. At Rome, Trajan was received as a winner and he took the name of Dacicus, a title that appears on his coinage of this period. At the beginning of the year 103 A.D., there were minted coins with the inscription: IMP NERVA TRAIANVS AVG GER DACICVS.

- "Assorted Imperial Battle Descriptions: Battle of Sarmizegetusa (Sarmizegetuza), A.D. 105". De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors.

However, during the years 103–105, Decebalus did not respect the peace conditions imposed by Trajan and the emperor then decided to destroy completely the Dacian kingdom and to conquer Sarmizegetuza.

Further reading

- András Mócsy, Pannonia and Upper Moesia: A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire, Routledge Revivals Series, 2014. ISBN 9781317754251

- Conor Whately, Exercitus Moesiae: The Roman Army in Moesia from Augustus to Severus Alexander. BAR international series, S2825. Oxford: 2016. ISBN 9781407314754