Avar–Byzantine wars

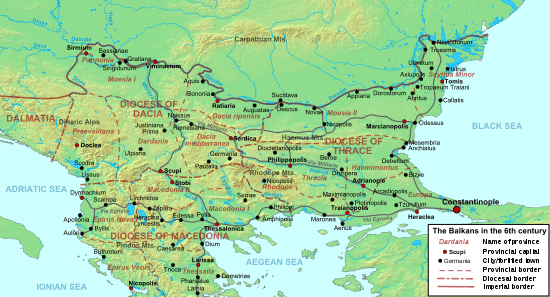

The Avar–Byzantine wars were a series of conflicts between the Byzantine Empire and the Avar Khaganate. The conflicts were initiated in 568, after the Avars arrived in Pannonia, and claimed all the former land of the Gepids and Lombards as their own. This led to them attempting to seize the city of Sirmium from Byzantium, which had previously retaken it from the Gepids, without success. Most of their future conflicts came as a result of raids by the Avars, or their subject Slavs, into the Balkan provinces of the Byzantine Empire.

The Avars usually raided the Balkans when the Byzantine Empire was distracted elsewhere, typically in its frequent wars with the Sassanid Empire in the East. As a result, they often raided without resistance for long periods of time, before Byzantine troops could be freed from other fronts to be sent on punitive expeditions. This happened during the 580s and 590s, where Byzantium was initially distracted in the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 572–591, but then followed up by a series of successful campaigns that pushed the Avars back.

Background

The Avars arrived in the Carpathian Basin in 568, fleeing from the First Turkic Khaganate. They quickly entered into an alliance with the Lombards to seize the land of the Gepids. However, during this process, the Lombards retreated to Italy, allowing the Avars to take both the lands of the Gepids and the former lands of the Lombards for themselves, creating the Avar Khaganate. The Avars then claimed all former territory of both as their own territory. This included Sirmium, which had been recently reconquered by the Byzantines from the Gepids, and would serve as the first cause of conflict between the Avars and the Byzantines.[1]

The Avars were heavily dependent upon the skills and labor of their subject peoples for both siege warfare and logistics. Subject peoples, such as the early Slavs and the Huns, had long traditions of engineering and craftsmanship, such as the building of boats and bridges, and the use of rams, tortoise formations, and artillery in sieges. In every documented use of siege engines by the Avars, the Avars depended upon subject peoples who had knowledge of them, usually the Sabirs, Kutrigurs, or Slavs. Avar military tactics also relied upon speed and shock.[2]

Avar attacks on Sirmium (568–582)

The Avars almost immediately launched an attack on Sirmium in 568, but were repulsed. The Avars withdrew their troops back to their own territory, but allegedly sent 10,000 Kotrigur Huns,[1] a people who like the Avars had been forced into the Carpathians by the Turkic Khaganate,[3] to invade the Byzantine province of Dalmatia. They then began a period of consolidation, during which the Byzantines paid them 80,000 gold solidi a year.[4] Except for a raid on Sirmium in 574,[1] they did not threaten Byzantine territory until 579, after Tiberius II stopped the payments.[4] The Avars retaliated with another siege of Sirmium.[5] The city fell in c. 581, or possibly 582. After the capture of Sirmium, the Avars demanded 100,000 solidi a year.[6] Refused, they began pillaging the northern and eastern Balkans, which only ended after the Avars were pushed back by the Byzantines from 597 to 602.[7]

Avar offensive in the Balkans (582–591)

After capturing Sirmium, the Avars began to rapidly encroach into the Balkans.[8] Their rapid spread was facilitated by the ongoing Byzantine–Sasanian War of 572–591, which left the Byzantine garrisons on the Danube frontier under-manned and underpaid. Because of this, the Avars and Slavs were able to raid without resistance, with the Byzantines only being able to harass raiding columns and set small ambushes, rather than forcing a decisive victory or launching a counteroffensive.[9] The Avars took the cities of Augustae, Singidunum, and Viminacium in 583, and a further eight of the nine cities by siege in 586. Many of these sieges relied upon the Avars utilizing both surprise and speed, advantages which they lost after they moved further inland in 587. Nevertheless they destroyed many cities in Moesia in 587 including Marcianopolis and Kabile though they failed in the sieges of Diocletianopolis, Philippopolis, and Beroe. In 588, they abandoned the siege of Singidunum after only seven days, in exchange for a meagre ransom. After this they succeeded at the siege of Anchialos, with the support of a fleet manned by Slavic auxiliaries, they then started and quickly abandoned the sieges of Drizipera and Tzurullon.[8] The Avars and Slavs continued to raid with little resistance until 591, when Emperor Maurice made a ceasefire treaty with the Sassanids in a fairly favorable terms, and shifted his focus to the Balkans.[9]

Roman counteroffensive (591–595)

After the peace treaty with the Persians and subsequent Roman refocusing on the Balkans as mentioned above, Maurice deployed veteran troops to the Balkans, allowing the Byzantines to shift from a reactive strategy to a pre-emptive one.[9] The general Priscus was tasked with stopping the Slavs from crossing the Danube in spring 593. He routed several raiding parties, before he crossed the Danube and fought the Slavs in what is now Wallachia until autumn. Maurice ordered him to make camp on the northern bank of the Danube, however Priscus instead retired to Odessos. Priscus' retreat allowed for a new Slav incursion in late 593/594 in Moesia and Macedonia, with the towns of Aquis, Scupi and Zaldapa being destroyed.[10]

In 594 Maurice replaced Priscus with his own brother, Peter. Due to his inexperience, Peter suffered initial failures, but eventually managed to repulse the tide of Slav and Avar incursions. He set up base at Marcianopolis, and patrolled the Danube between Novae and the Black Sea. In late August of 594, he crossed the Danube near Securisca and fought his way to the Helibacia river, preventing the Slavs and Avars from preparing new pillaging campaigns.[11] Priscus, who had been given command of another army, prevented the Avars from besieging Singidunum in 595, in combination with the Byzantine Danube fleet. After this, the Avars shifted their focus to Dalmatia, where they sacked several fortresses, and avoided confronting Priscus directly. Priscus was not particularly concerned about the Avar incursion, as Dalmatia was a remote and poor province; he sent only a small force to check their invasion, keeping the main body of his forces near the Danube. The small force was able to hamper the Avar advance, and even recovered a part of the loot taken by the Avars, better than expected.[12]

First interlude (595–597)

After their invasion of Dalmatia had been blocked, the Avars were discouraged by their lack of success against the Byzantines, and thus began to make their raids against the Franks, who they saw as being easier to attack, launching major raids against them in 596. Due to the shift in focus, there was little activity in the Balkans from 595 to 597.[13]

Avar invasion (597–602)

Emboldened by the plunder from the Franks, the Avars resumed their raids across the Danube in autumn of 597, catching the Byzantines by surprise. The Avars even caught Priscus' army while it was still in its camp in Tomis, and laid siege to it. However, they lifted the siege on 30 March 598, at the approach of an Byzantine army led by Comentiolus, which had just crossed Mount Haemus and was marching along the Danube up to Zikidiba, only 30 kilometres (19 mi) from Tomis.[14] For unknown reasons, Priscus did not join Comentiolus when he pursued the Avars. Comentiolus made camp at Iatrus, however he was routed by the Avars, and his troops had to fight their way back over the Haemus. The Avars took advantage of this victory and advanced to Drizipera, near Constantinople. At Drizipera the Avar forces were struck by a plague, leading to the death of a large portion of their army, and seven sons of Bayan, the Avar Khagan.[15]

Due to the threat posed by the Avar forces at Drizipera, Comentiolus was replaced with Philippicus, and recalled to Constantinople.[16] Maurice assembled a force made up of the Circus Factions and his bodyguards to defend the Anastasian Wall.[17] Maurice then paid off the Avars for a temporary truce,[14] spending the rest of 598 in reorganizing his forces and analyzing how to improve the Byzantines' strategy.[17] In the same year, the Byzantines concluded a peace treaty with the Avars, which allowed the Byzantines to send expeditions into Wallachia.[18]

Ignoring the peace treaty, the Byzantines made preparations to invade the Avars' land. Priscus set up expeditionary camp near Singidunum and wintered there in 598/599. In 599 Priscus and Comentiolus led their troops downstream to Viminacium, and crossed the Danube. Once on the north bank, they defeated the Avars in the Battles of Viminacium. This battle was significant, as it was the first time the Avars suffered a major defeat in their home territory, and also led to the deaths of several more of Bayan's sons. After the battle, Priscus led his forces north into the Pannonian plain, engaging and defeating the Avars deep within their heartland. Comentiolus meanwhile remained near the Danube, to guard it.[19] Priscus devastated the lands east of the Tisza, inflicting heavy casualties on the Avars and Gepids,[20][21] and defeating them in two further battles on the banks of the Tisza.[22] In autumn 599, Comentiolus reopened the Gates of Trajan, which had not been used by the Byzantines for decades. In 601 Peter led troops to the banks of the Tisza, to defend the Danube cataracts, which were vital to the Byzantine Danube fleet's access to the cities of Sirmium and Singidunum.[21] The next year, in 602, the Antes began to invade the Avars' land, who were already on the brink of collapse due to the uprisings of several Avar tribes,[23] one of whom even defected to the Byzantines.[22]

Second interlude (602–612)

After being beaten back by the Byzantines under Maurice, the Avars shifted their focus to Italy, establishing diplomatic contact in 603, and attempting an invasion of North Italy in 610.[7] The Balkan frontier was largely pacified, for the first time since the reign of Anastasius I (r. 491–518). Maurice planned to repopulate the devastated lands which the Byzantines had recovered by settling Armenian peasants, whose homeland was the eastern part opposite to the Western Balkan part in the Empire -It was a deliberately enforced imperial strategy in order to prevent ethnic/tribal consolidation as the independent rebellious forces-, as well as Romanizing the Slavic settlers already in the area. Maurice also planned to lead further campaigns against the Avar Khaganate, so as to either destroy them or force them into submission. However, Maurice was overthrown in 602 by Phocas, as his army rebelled against the endless Balkan campaigning.[24] Phocas promptly scrapped those plans.[25]

Phocas maintained the security of the Balkans during his reign from 602 to 610, although he did withdraw some forces from the Balkans in 605, in order to use them in the ongoing Byzantine-Sassanid War of 602–628. There is no archaeological evidence of Slavic or Avar incursions during this time.[26][27] While the lack of Byzantine action or presence may have encouraged the Avars,[26] they did not attack Byzantine territory until c. 615, when Emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641) withdrew his troops stationed in the Balkans in order to fend off the Persian advance in the East.[7]

Renewed Avar attacks (612–626)

The Avars, who were likely encouraged by their successful campaigns against the Lombards in 610 and the Franks in 611, resumed their incursions some time after 612. By 614, with the Persian capture of Jerusalem, it became clear to the Avars and their Slav subjects that retaliation from the Byzantines was extremely unlikely. Chronicles of the 610s record wholesale pillaging, with cities such as Justiniana Prima and Salona fallen.[26] The cities of Naissus and Serdica were captured in 615, and the cities of Novae and Justiniana Prima were destroyed in 613 and 615, respectively. The Slavs also raided in the Aegean, as far as Crete, in 623. During this time period, there were three separate sieges of Thessalonica: in 604, 615, and 617.[28] In 623 the Byzantine emperor Heraclius journeyed into Thrace in an attempt to agree peace with the Avar Khagan face to face. Instead the Byzantines were ambushed, with Heraclius narrowly escaping and most of his bodyguard and retainers being killed or captured.[29] The Avar raids continued, culminating in the Siege of Constantinople in 626, where the Avars were finally defeated.[27][28]

Siege of Constantinople (626)

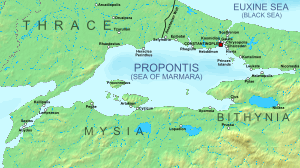

The Persian king Khosrau II, after suffering reverses through Heraclius' campaigns in the Persian rear, resolved to launch a decisive strike.[30] While general Shahin Vahmanzadegan was sent to stop Heraclius with 50,000 men, Shahrbaraz was given command of a smaller army and ordered to slip by Heraclius' flank, and march for Chalcedon, a Persian base across the Bosporus from Constantinople. Khosrau II also made contact with the Khagan of the Avars to allow for a coordinated attack on Constantinople, the Persians on the Asiatic side, and the Avars from the European side.[31]

The Avar army approached Constantinople from Thrace and destroyed the Aqueduct of Valens.[32] Because the Byzantine navy controlled the Bosporus strait, the Persians could not send troops to the European side to aid the Avars,[33] which cut off the Persian access to the Avars with the Persian expertise in siege warfare.[34] Byzantine naval superiority also made communication between the two forces difficult.[31][35] Constantinople's defenders were under the command of Patriarch Sergius and the patrician Bonus.[36]

On 29 June 626, the Avars and Persians began a coordinated assault upon the walls. The Byzantine defenders had 12,000 well-trained cavalry troops, who were likely dismounted, facing roughly 80,000 Avars and Sclaveni (Slavs whose land was controlled by the Avars).[30] Because the Persian base in Chalcedon had been established for many years, it was not immediately obvious that a siege would take place. It only became obvious to the Byzantines after the Avars began to move heavy siege equipment towards the Theodosian Walls. Although the walls had been continuously bombarded for a month, high morale had been maintained in the city; Patriarch Sergius bolstered morale by leading processions along the tops of the walls, carrying the Blachernitissa icon of the Virgin Mary.[37][38] The peasantry around Constantinople were rallied by this religious zeal, especially because both forces attacking Constantinople were non-Christians.[37]

On August 7, a fleet of Persian rafts ferrying troops across the Bosporus to the European side were surrounded and destroyed by the Byzantine fleet. The Sclaveni then attempted to attack the Sea Walls from across the Golden Horn, while the Avars attacked the land walls. However, the Sclaveni boats were rammed and destroyed by the galleys of Bonus, and the Avar land assaults on August 6 and 7 were repelled.[39] At around this point, the news that the Emperor's brother Theodore had decisively defeated Shahin arrived, leading the Avars to retreat to the Balkan hinterland within two days. They would never seriously threaten Constantinople again. Even though the Persian army of Shahrbaraz still remained at Chalcedon, the threat to Constantinople was over, as the Persians could not use artillery from their side of the Bosporus.[36][37] In thanks for the lifting of the siege and the supposed divine protection granted by the Virgin Mary, the celebrated Akathist Hymn was written by an unknown author, possibly Patriarch Sergius or George of Pisidia.[40][41]

Avar decline (626–822)

.png)

After failing to capture Constantinople, the Avars rapidly began to decline before disintegrating entirely,[42] due to both internal power struggles, and conflicts with the Bulgars and Sclaveni.[43] After their hegemony over various tribal peoples collapsed, their land was further reduced by the Bulgars around 680, leaving behind a rump state which remained until their conquest by Charlemagne, starting in 790 and ending in 803.[7]

References

Primary sources

- De Administrando Imperio, by the 10th-century emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos.[44]

- Strategikon, attributed to Emperor Maurice.[44]

- Miracula Sancti Demetrii, by John, Archbishop of Thessalonica.[45]

- Surviving fragments of Menander Protector.[7]

Citations

- Petersen 2013, p. 378.

- Petersen 2013, pp. 379–382.

- Golden 2011, p. 140.

- Mitchell 2007, p. 405.

- Petersen 2013, pp. 378–379.

- Mitchell 2007, p. 406.

- Petersen 2013, p. 379.

- Petersen 2013, p. 381.

- Crawford 2013, p. 25.

- Whitby 1998, p. 159f.

- Whitby 1998, p. 160f.

- Whitby 1998, p. 161.

- Whitby 1998, pp. 161–162.

- Whitby 1998, p. 162.

- Whitby 1998, pp. 162–163.

- Pohl 2002, p. 153.

- Whitby 1998, p. 163.

- Pohl 2002, p. 154.

- Pohl 2002, p. 156.

- Pohl 2002, p. 157.

- Whitby 1998, p. 164.

- Pohl 2002, p. 158.

- Whitby 1998, p. 165.

- Mitchell 2007, p. 408.

- Whitby 1998, p. 184f.

- Whitby 1998, p. 187.

- Curta 2001, p. 189.

- Maier 1973, p. 81.

- Mitchell 2007, p. 413.

- Norwich 1997, p. 92.

- Oman 1893, p. 210.

- Treadgold 1997, p. 297.

- Kaegi 2003, pp. 133, 140.

- Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 179–181.

- Kaegi 2003, p. 134.

- Oman 1893, p. 211.

- Norwich 1997, p. 93.

- Kaegi 2003, p. 136.

- Kaegi 2003, p. 137.

- Ekonomou 2008, p. 285.

- Gambero 1999, p. 338.

- Hupchick 2017, p. 48.

- Chaliand 2014, p. 81.

- Petersen 2013, p. 380.

- Petersen 2013, p. 383.

Bibliography

- Chaliand, Gérard (2014). A Global History of War: From Assyria to the Twenty-First Century. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520959439.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crawford, Peter (2013). The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 9781848846128.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c.500–700. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139428880.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dodgeon, Michael H.; Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars: AD 363-630: a Narrative Sourcebook. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415146876.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ekonomou, Andrew J. (2008). Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes: Eastern Influences on Rome and the Papacy from Gregory the Great to Zacharias, AD 590–752. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0739119778.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gambero, Luigi (1999). Mary and the Fathers of the Church: The Blessed Virgin Mary in Patristic Thought. Translated by Thomas Buffer. Ignatius. ISBN 978-0898706864.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Golden, Peter B. (2011). Studies on the Peoples and Cultures of the Eurasian Steppes. Editura Academiei Române; Editura Istros a Muzeului Brăilei. ISBN 9789732721520.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hupchick, Dennis P. (2017). The Bulgarian-Byzantine Wars for Early Medieval Balkan Hegemony: Silver-Lined Skulls and Blinded Armies. Springer. ISBN 9783319562063.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaegi, Walter Emil (2003). Heraclius: Emperor of Byzantium. CUP. ISBN 978-0521814591.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maier, Franz Georg (1973). Fischer World Histories Volume 13: Byzantium (in German). Fischer TB. ASIN B007E1L89K.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Stephen (2007). A History of the Later Roman Empire. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-0856-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. Knopf. ISBN 978-0679450887.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oman, Charles (1893) [2012]. "XII Heraclius and Mohammed 610–641". In Arthur Hassall (ed.). Europe, 476–918. Periods of European History. Period I. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1272944186.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petersen, Leif Inge Ree (2013). Siege Warfare and Military Organization in the Successor States (400-800 AD) Byzantium, the West and Islam. BRILL. ISBN 9789004254466.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pohl, Walter (2002). The Avars: a Steppe People in Central Europe, 567-822 AD (in German). Beck. ISBN 9783406489693.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whitby, Michael (1998). The Emperor Maurice and his Historian – Theophylact Simocatta on Persian and Balkan Warfare. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822945-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)