Alan Lomax

Alan Lomax (/ˈloʊmæks/; January 31, 1915 – July 19, 2002) was an American ethnomusicologist, best known for his numerous field recordings of folk music of the 20th century. He was also a musician himself, as well as a folklorist, archivist, writer, scholar, political activist, oral historian, and film-maker. Lomax produced recordings, concerts, and radio shows in the US and in England, which played an important role in preserving folk music traditions in both countries, and helped start both the American and British folk revivals of the 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s. He collected material first with his father, folklorist and collector John A. Lomax, and later alone and with others, Lomax recorded thousands of songs and interviews for the Archive of American Folk Song, of which he was the director, at the Library of Congress on aluminum and acetate discs.

Alan Lomax | |

|---|---|

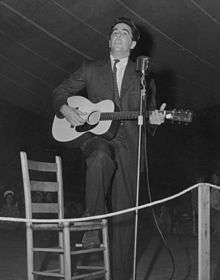

Lomax playing guitar on stage at the Mountain Music Festival, Asheville, North Carolina, in the early 1940s. | |

| Background information | |

| Born | January 31, 1915 Austin, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | July 19, 2002 (aged 87) Safety Harbor, Florida, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Folklorist, ethnomusicologist, musician |

| Part of a series on the |

| Anthropology of art, media, music, dance and film |

|---|

|

Basic concepts |

| Social and cultural anthropology |

After 1942, when Congress cut off the Library of Congress's funding for folk song collecting, Lomax continued to collect independently in Britain, Ireland, the Caribbean, Italy, and Spain, as well as the United States, using the latest recording technology, assembling an enormous collection of American and international culture. In March 2004 the material captured and produced without Library of Congress funding was acquired by the Library, which "brings the entire seventy years of Alan Lomax's work together under one roof at the Library of Congress, where it has found a permanent home."[1] With the start of the Cold War, Lomax continued to speak out for a public role for folklore,[2] even as academic folklorists turned inward. He devoted much of the latter part of his life to advocating what he called Cultural Equity, which he sought to put on a solid theoretical foundation through to his Cantometrics research (which included a prototype Cantometrics-based educational program, the Global Jukebox). In the 1970s and 1980s Lomax advised the Smithsonian Institution's Folklife Festival and produced a series of films about folk music, American Patchwork, which aired on PBS in 1991. In his late seventies, Lomax completed a long-deferred memoir, The Land Where the Blues Began (1995), linking the birth of the blues to debt peonage, segregation, and forced labor in the American South.

Lomax's greatest legacy is in preserving and publishing recordings of musicians in many folk and blues traditions around the US and Europe. Among the artists Lomax is credited with discovering and bringing to a wider audience include blues guitarist Robert Johnson, protest singer Woody Guthrie, folk artist Pete Seeger, country musician Burl Ives, and country blues singer Lead Belly, among many others. "Alan scraped by the whole time, and left with no money," said Don Fleming, director of Lomax's Association for Culture Equity. "He did it out of the passion he had for it, and found ways to fund projects that were closest to his heart." [3]

Biography

Early life

Lomax was born in Austin, Texas, in 1915,[4][5] the third of four children born to Bess Brown and pioneering folklorist and author John A. Lomax.

The elder Lomax, a former professor of English at Texas A&M and a celebrated authority on Texas folklore and cowboy songs, had worked as an administrator, and later Secretary of the Alumni Society, of the University of Texas.

Due to childhood asthma, chronic ear infections, and generally frail health, Lomax had mostly been home schooled in elementary school. In Dallas, he entered the Terrill School for Boys (a tiny prep school that later became St. Mark's School of Texas). Lomax excelled at Terrill and then transferred to the Choate School (now Choate Rosemary Hall) in Connecticut for a year, graduating eighth in his class at age 15 in 1930.[6]

Owing to his mother's declining health, however, rather than going to Harvard as his father had wished, Lomax matriculated at the University of Texas at Austin. A roommate, future anthropologist Walter Goldschmidt, recalled Lomax as "frighteningly smart, probably classifiable as a genius", though Goldschmidt remembers Lomax exploding one night while studying: "Damn it! The hardest thing I've had to learn is that I'm not a genius."[7] At the University of Texas Lomax read Nietzsche and developed an interest in philosophy. He joined and wrote a few columns for the school paper, The Daily Texan but resigned when it refused to publish an editorial he had written on birth control.[7]

At this time he also he began collecting "race" records and taking his dates to black-owned night clubs, at the risk of expulsion. During the spring term his mother died, and his youngest sister Bess, age 10, was sent to live with an aunt. Although the Great Depression was rapidly causing his family's resources to plummet, Harvard came up with enough financial aid for the 16-year-old Lomax to spend his second year there. He enrolled in philosophy and physics and also pursued a long-distance informal reading course in Plato and the Pre-Socratics with University of Texas professor Albert P. Brogan.[8] He also became involved in radical politics and came down with pneumonia. His grades suffered, diminishing his financial aid prospects.[9]

Lomax, now 17, therefore took a break from studying to join his father's folk song collecting field trips for the Library of Congress, co-authoring American Ballads and Folk Songs (1934) and Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly (1936). His first field collecting without his father was done with Zora Neale Hurston and Mary Elizabeth Barnicle in the summer of 1935. He returned to the University of Texas that fall and was awarded a BA in Philosophy, summa cum laude, and membership in Phi Beta Kappa in May 1936.[10] Lack of money prevented him from immediately attending graduate school at the University of Chicago, as he desired, but he would later correspond with and pursue graduate studies with Melville J. Herskovits at Columbia University and with Ray Birdwhistell at the University of Pennsylvania.

Alan Lomax married Elizabeth Harold Goodman, then a student at the University of Texas, in February 1937.[11] They were married for 12 years and had a daughter, Anne (later known as Anna). Elizabeth assisted him in recording in Haiti, Alabama, Appalachia, and Mississippi. Elizabeth also wrote radio scripts of folk operas featuring American music that were broadcast over the BBC Home Service as part of the war effort.

During the 1950s, after she and Lomax divorced, she conducted lengthy interviews for Lomax with folk music personalities, including Vera Ward Hall and the Reverend Gary Davis. Lomax also did important field work with Elizabeth Barnicle and Zora Neale Hurston in Florida and the Bahamas (1935); with John Wesley Work III and Lewis Jones in Mississippi (1941 and 42); with folksingers Robin Roberts[12] and Jean Ritchie in Ireland (1950); with his second wife Antoinette Marchand in the Caribbean (1961); with Shirley Collins in Great Britain and the Southeastern US (1959); with Joan Halifax in Morocco; and with his daughter. All those who assisted and worked with him were accurately credited on the resultant Library of Congress and other recordings, as well as in his many books, films, and publications.

Assistant in Charge and Commercial Records and Radio Broadcasts

From 1937 to 1942, Lomax was Assistant in Charge of the Archive of Folk Song of the Library of Congress to which he and his father and numerous collaborators contributed more than ten thousand field recordings. A pioneering oral historian, Lomax recorded substantial interviews with many folk and jazz musicians, including Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Jelly Roll Morton and other jazz pioneers, and Big Bill Broonzy. On one of his trips in 1941, he went to Clarksdale, Mississippi, hoping to record the music of Robert Johnson. When he arrived, we was told by locals that Johnson had died but that another local man - Muddy Waters - might be willing to record his music for Lomax. Using recording equipment that filled the trunk of his car, Lomax recorded Waters' music; it is said that hearing Lomax's recording was the motivation that Waters needed to leave his farm job in Mississippi to pursue a career as a blues musician, first in Memphis and later in Chicago.[13]

As part of this work, Lomax traveled through Michigan and Wisconsin in 1938 to record and document the traditional music of that region. Over four hundred recordings from this collection are now available at the Library of Congress. "He traveled in a 1935 Plymouth sedan, toting a Presto instantaneous disc recorder and a movie camera. And when he returned nearly three months later, having driven thousands of miles on barely paved roads, it was with a cache of 250 discs and 8 reels of film, documents of the incredible range of ethnic diversity, expressive traditions, and occupational folklife in Michigan."[14]

In late 1939, Lomax hosted two series on CBS's nationally broadcast American School of the Air, called American Folk Song and Wellsprings of Music, both music appreciation courses that aired daily in the schools and were supposed to highlight links between American folk and classical orchestral music. As host, Lomax sang and presented other performers, including Burl Ives, Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Pete Seeger, Josh White, and the Golden Gate Quartet. The individual programs reached ten million students in 200,000 U.S. classrooms and were also broadcast in Canada, Hawaii, and Alaska, but both Lomax and his father felt that the concept of the shows, which portrayed folk music as mere raw material for orchestral music, was deeply flawed and failed to do justice to vernacular culture.

In 1940 under Lomax's supervision, RCA made two groundbreaking suites of commercial folk music recordings: Woody Guthrie's Dust Bowl Ballads and Lead Belly's Midnight Special and Other Southern Prison Songs.[15] Though they did not sell especially well when released, Lomax's biographer, John Szwed calls these "some of the first concept albums."[16]

In 1940, Lomax and his close friend Nicholas Ray went on to write and produce a fifteen-minute program, Back Where I Came From, which aired three nights a week on CBS and featured folk tales, proverbs, prose, and sermons, as well as songs, organized thematically. Its racially integrated cast included Burl Ives, Lead Belly, Josh White, Sonny Terry, and Brownie McGhee. In February 1941, Lomax spoke and gave a demonstration of his program along with talks by Nelson A. Rockefeller from the Pan American Union, and the president of the American Museum of Natural History, at a global conference in Mexico of a thousand broadcasters CBS had sponsored to launch its worldwide programming initiative. Mrs. Roosevelt invited Lomax to Hyde Park.[17]

Despite its success and high visibility, Back Where I Come From never picked up a commercial sponsor. The show ran for only twenty-one weeks before it was suddenly canceled in February 1941.[18] On hearing the news Woody Guthrie wrote Lomax from California, "Too honest again, I suppose? Maybe not purty enough. O well, this country's a getting to where it can't hear its own voice. Someday the deal will change."[19] Lomax himself wrote that in all his work he had tried to capture "the seemingly incoherent diversity of American folk song as an expression of its democratic, inter-racial, international character, as a function of its inchoate and turbulent many-sided development." [20]

On December 8, 1941, as "Assistant in Charge at the Library of Congress", he sent telegrams to fieldworkers in ten different localities across the United States, asking them to collect reactions of ordinary Americans to the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent declaration of war by the United States. A second series of interviews, called "Dear Mr. President", was recorded in January and February 1942.[21]

While serving in the Army in World War II Lomax produced and hosted numerous radio programs in connection with the war effort. The 1944 "ballad opera", The Martins and the Coys, broadcast in Britain (but not the USA) by the BBC, featuring Burl Ives, Woody Guthrie, Will Geer, Sonny Terry, Pete Seeger, and Fiddlin' Arthur Smith, among others, was released on Rounder Records in 2000.[22]

In the late 1940s, Lomax produced a series of commercial folk music albums for Decca Records and organized a series of concerts at New York's Town Hall and Carnegie Hall, featuring blues, calypso, and flamenco music. He also hosted a radio show, Your Ballad Man, in 1949 that was broadcast nationwide on the Mutual Radio Network and featured a highly eclectic program, from gamelan music, to Django Reinhardt, to Klezmer music, to Sidney Bechet and Wild Bill Davison, to jazzy pop songs by Maxine Sullivan and Jo Stafford, to readings of the poetry of Carl Sandburg, to hillbilly music with electric guitars, to Finnish brass bands – to name a few.[23] He also was a key participant in the V. D. Radio Project in 1949, creating a number of "ballad dramas" featuring country and gospel superstars, including Roy Acuff, Woody Guthrie, Hank Williams, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe (among others), that aimed to convince men and women suffering from syphilis to seek treatment.[24]

Move to Europe and later life

In December 1949 a newspaper printed a story, "Red Convictions Scare 'Travelers'", that mentioned a dinner given by the Civil Rights Association to honor five lawyers who had defended people accused of being Communists. The article mentioned Alan Lomax as one of the sponsors of the dinner, along with C. B. Baldwin, campaign manager for Henry A. Wallace in 1948; music critic Olin Downes of The New York Times; and W. E. B. Du Bois, all of whom it accused of being members of Communist front groups.[25] The following June, Red Channels, a pamphlet edited by former F.B.I. agents which became the basis for the entertainment industry blacklist of the 1950s, listed Lomax as an artist or broadcast journalist sympathetic to Communism. (Others listed included Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, Yip Harburg, Lena Horne, Langston Hughes, Burl Ives, Dorothy Parker, Pete Seeger, and Josh White.) That summer, Congress was debating the McCarran Act, which would require the registration and fingerprinting of all "subversives" in the United States, restrictions of their right to travel, and detention in case of "emergencies,"[26] while the House Un-American Activities Committee was broadening its hearings. Feeling sure that the Act would pass and realizing that his career in broadcasting was in jeopardy, Lomax, who was newly divorced and already had an agreement with Goddard Lieberson of Columbia Records to record in Europe,[27] hastened to renew his passport, cancel his speaking engagements, and plan for his departure, telling his agent he hoped to return in January "if things cleared up." He set sail on September 24, 1950, on board the steamer RMS Mauretania. Sure enough, in October, FBI agents were interviewing Lomax's friends and acquaintances. Lomax never told his family exactly why he went to Europe, only that he was developing a library of world folk music for Columbia. Nor would he ever allow anyone to say he was forced to leave. In a letter to the editor of a British newspaper, Lomax took a writer to task for describing him as a "victim of witch-hunting," insisting that he was in the UK only to work on his Columbia Project.[28]

Lomax spent the 1950s based in London, from where he edited the 18-volume Columbia World Library of Folk and Primitive Music, an anthology issued on newly invented LP records. He spent seven months in Spain, where, in addition to recording three thousand items from most of the regions of Spain, he made copious notes and took hundreds of photos of "not only singers and musicians but anything that interested him – empty streets, old buildings, and country roads", bringing to these photos, "a concern for form and composition that went beyond the ethnographic to the artistic".[29] He drew a parallel between photography and field recording:

Recording folk songs works like a candid cameraman. I hold the mike, use my hand for shading volume. It's a big problem in Spain because there is so much emotional excitement, noise all around. Empathy is most important in field work. It's necessary to put your hand on the artist while he sings. They have to react to you. Even if they're mad at you, it's better than nothing.[29]

When Columbia Records producer George Avakian gave jazz arranger Gil Evans a copy of the Spanish World Library LP, Miles Davis and Evans were "struck by the beauty of pieces such as the 'Saeta', recorded in Seville, and a panpiper's tune ('Alborada de Vigo') from Galicia, and worked them into the 1960 album, Sketches of Spain."[30]

For the Scottish, English, and Irish volumes, he worked with the BBC and folklorists Peter Douglas Kennedy, Scots poet Hamish Henderson, and with the Irish folklorist Séamus Ennis,[31] recording among others, Margaret Barry and the songs in Irish of Elizabeth Cronin; Scots ballad singer Jeannie Robertson; and Harry Cox of Norfolk, England, and interviewing some of these performers at length about their lives. In 1953 a young David Attenborough commissioned Lomax to host six 20-minute episodes of a BBC TV series, The Song Hunter, which featured performances by a wide range of traditional musicians from all over Britain and Ireland, as well as Lomax himself.[32] In 1957 Lomax hosted a folk music show on BBC's Home Service called 'A Ballad Hunter' and organized a skiffle group, Alan Lomax and the Ramblers (who included Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger, and Shirley Collins, among others), which appeared on British television. His ballad opera, Big Rock Candy Mountain, premiered December 1955 at Joan Littlewood's Theater Workshop and featured Ramblin' Jack Elliot. In Scotland, Lomax is credited with being an inspiration for the School of Scottish Studies, founded in 1951, the year of his first visit there.[33][34]

Lomax and Diego Carpitella's survey of Italian folk music for the Columbia World Library, conducted in 1953 and 1954, with the cooperation of the BBC and the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome, helped capture a snapshot of a multitude of important traditional folk styles shortly before they disappeared. The pair amassed one of the most representative folk song collections of any culture. From Lomax's Spanish and Italian recordings emerged one of the first theories explaining the types of folk singing that predominate in particular areas, a theory that incorporates work style, the environment, and the degrees of social and sexual freedom.

Return to the United States

Upon his return to New York in 1959, Lomax produced a concert, Folksong '59, in Carnegie Hall, featuring Arkansas singer Jimmy Driftwood; the Selah Jubilee Singers and Drexel Singers (gospel groups); Muddy Waters and Memphis Slim (blues); Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys (bluegrass); Pete Seeger, Mike Seeger (urban folk revival); and The Cadillacs (a rock and roll group). The occasion marked the first time rock and roll and bluegrass were performed on the Carnegie Hall Stage. "The time has come for Americans not to be ashamed of what we go for, musically, from primitive ballads to rock 'n' roll songs", Lomax told the audience. According to Izzy Young, the audience booed when he told them to lay down their prejudices and listen to rock 'n' roll. In Young's opinion, "Lomax put on what is probably the turning point in American folk music . . . . At that concert, the point he was trying to make was that Negro and white music were mixing, and rock and roll was that thing."[35]

Alan Lomax had met 20-year-old English folk singer Shirley Collins while living in London. The two were romantically involved and lived together for some years. When Lomax obtained a contract from Atlantic Records to re-record some of the American musicians first recorded in the 1940s, using improved equipment, Collins accompanied him. Their folk song collecting trip to the Southern states, known colloquially as the Southern Journey, lasted from July to November 1959 and resulted in many hours of recordings, featuring performers such as Almeda Riddle, Hobart Smith, Wade Ward, Charlie Higgins and Bessie Jones and culminated in the discovery of Fred McDowell. Recordings from this trip were issued under the title Sounds of the South and some were also featured in the Coen brothers' 2000 film O Brother, Where Art Thou?. Lomax wished to marry Collins but when the recording trip was over, she returned to England and married Austin John Marshall. In an interview in The Guardian newspaper, Collins expressed irritation that Alan Lomax's 1993 account of the journey, The Land Where The Blues Began, barely mentioned her. "All it said was, 'Shirley Collins was along for the trip'. It made me hopping mad. I wasn't just 'along for the trip'. I was part of the recording process, I made notes, I drafted contracts, I was involved in every part".[36] Collins addressed the perceived omission in her memoir, America Over the Water, published in 2004.[37][38]

Lomax married Antoinette Marchand on August 26, 1961. They separated the following year and were divorced in 1967.[39]

In 1962, Lomax and singer and Civil Rights Activist Guy Carawan, music director at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, produced the album, Freedom in the Air: Albany Georgia, 1961–62, on Vanguard Records for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Lomax was a consultant to Carl Sagan for the Voyager Golden Record sent into space on the 1977 Voyager Spacecraft to represent the music of the earth. Music he helped choose included the blues, jazz, and rock 'n' roll of Blind Willie Johnson, Louis Armstrong, and Chuck Berry; Andean panpipes and Navajo chants; Azerbaijani mugham performed by two balaban players,[40] a Sicilian sulfur miner's lament; polyphonic vocal music from the Mbuti Pygmies of Zaire, and the Georgians of the Caucasus; and a shepherdess song from Bulgaria by Valya Balkanska;[41] in addition to Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, and more. Sagan later wrote that it was Lomax "who was a persistent and vigorous advocate for including ethnic music even at the expense of Western classical music. He brought pieces so compelling and beautiful that we gave in to his suggestions more often than I would have thought possible. There was, for example, no room for Debussy among our selections, because Azerbaijanis play bagpipe-sounding instruments [balaban] and Peruvians play panpipes and such exquisite pieces had been recorded by ethnomusicologists known to Lomax."[42]

Alan Lomax died in Safety Harbor, Florida on July 19, 2002 at the age of 87.[43]

Cultural equity

The dimension of cultural equity needs to be added to the humane continuum of liberty, freedom of speech and religion, and social justice.[44]

Folklore can show us that this dream is age-old and common to all mankind. It asks that we recognize the cultural rights of weaker peoples in sharing this dream. And it can make their adjustment to a world society an easier and more creative process. The stuff of folklore—the orally transmitted wisdom, art and music of the people can provide ten thousand bridges across which men of all nations may stride to say, "You are my brother."[45]

As a member of the Popular Front and People's Songs in the 1940s, Alan Lomax promoted what was then known as "One World" and today is called multiculturalism.[46] In the late forties he produced a series of concerts at Town Hall and Carnegie Hall that presented flamenco guitar and calypso, along with country blues, Appalachian music, Andean music, and jazz. His radio shows of the 1940s and 1950s explored musics of all the world's peoples.

Lomax recognized that folklore (like all forms of creativity) occurs at the local and not the national level and flourishes not in isolation but in fruitful interplay with other cultures. He was dismayed that mass communications appeared to be crushing local cultural expressions and languages. In 1950 he echoed anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski (1884–1942), who believed the role of the ethnologist should be that of advocate for primitive man (as indigenous people were then called), when he urged folklorists to similarly advocate for the folk. Some, such as Richard Dorson, objected that scholars shouldn't act as cultural arbiters, but Lomax believed it would be unethical to stand idly by as the magnificent variety of the world's cultures and languages was "grayed out" by centralized commercial entertainment and educational systems. Although he acknowledged potential problems with intervention, he urged that folklorists with their special training actively assist communities in safeguarding and revitalizing their own local traditions.

Similar ideas had been put into practice by Benjamin Botkin, Harold W. Thompson, and Louis C. Jones, who believed that folklore studied by folklorists should be returned to its home communities to enable it to thrive anew. They have been realized in the annual (since 1967) Smithsonian Folk Festival on the Mall in Washington, D.C. (for which Lomax served as a consultant), in national and regional initiatives by public folklorists and local activists in helping communities gain recognition for their oral traditions and lifeways both in their home communities and in the world at large; and in the National Heritage Awards, concerts, and fellowships given by the NEA and various State governments to master folk and traditional artists.[47]

In 1983, Lomax founded The Association for Cultural Equity (ACE). It is housed at the Fine Arts Campus of Hunter College in New York City and is the custodian of the Alan Lomax Archive. The Association's mission is to "facilitate cultural equity" and practice "cultural feedback" and "preserve, publish, repatriate and freely disseminate" its collections.[48] Though Alan Lomax's appeals to anthropology conferences and repeated letters to UNESCO fell on deaf ears, the modern world seems to have caught up to his vision. In an article first published in the 2009 Louisiana Folklore Miscellany, Barry Jean Ancelet, folklorist and chair of the Modern Languages Department at University of Louisiana at Lafayette, wrote:

Every time [Lomax] called me over a span of about ten years, he never failed to ask if we were teaching Cajun French in the schools yet. His notions about the importance of cultural and linguistic diversity have been affirmed by many contemporary scholars, including Nobel Prize-winning physicist Murray Gell-Mann who concluded his recent book, The Quark and the Jaguar, with a discussion of these very same issues, insisting on the importance of "cultural DNA" (1994: 338–343). His cautions about "universal popular culture" (1994: 342) sound remarkably like Alan's warning in his "Appeal for Cultural Equity" that the "cultural grey-out" must be checked or there would soon be "no place worth visiting and no place worth staying" (1972). Compare Gell-Mann:

Just as it is crazy to squander in a few decades much of the rich biological diversity that has evolved over billions of years, so is it equally crazy to permit the disappearance of much of human cultural diversity, which has evolved in a somewhat analogous way over many tens of thousands of years… The erosion of local cultural patterns around the world is not, however, entirely or even principally the result of contact with the universalizing effect of scientific enlightenment. Popular culture is in most cases far more effective at erasing distinctions between one place or society and another. Blue jeans, fast food, rock music, and American television serials have been sweeping the world for years. (1994: 338–343)and Lomax:

carcasses of dead or dying cultures on the human landscape, that we have learned to dismiss this pollution of the human environment as inevitable, and even sensible, since it is wrongly assumed that the weak and unfit among musics and cultures are eliminated in this way… Not only is such a doctrine anti-human; it is very bad science. It is false Darwinism applied to culture – especially to its expressive systems, such as music language, and art. Scientific study of cultures, notably of their languages and their musics, shows that all are equally expressive and equally communicative, even though they may symbolize technologies of different levels… With the disappearance of each of these systems, the human species not only loses a way of viewing, thinking, and feeling but also a way of adjusting to some zone on the planet which fits it and makes it livable; not only that, but we throw away a system of interaction, of fantasy and symbolizing which, in the future, the human race may sorely need. The only way to halt this degradation of man's culture is to commit ourselves to the principles of political, social, and economic justice. (2003 [1972]: 286)[49]

In 2001, in the wake of the attacks in New York and Washington of September 11, UNESCO's Universal Declaration of Cultural Diversity declared the safeguarding of languages and intangible culture on a par with protection of individual human rights and as essential for human survival as biodiversity is for nature,[50] ideas remarkably similar to those forcefully articulated by Alan Lomax many years before.

FBI investigations

From 1942 to 1979 Lomax was repeatedly investigated and interviewed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), although nothing incriminating was ever discovered and the investigation was eventually abandoned. Scholar and jazz pianist Ted Gioia uncovered and published extracts from Alan Lomax's 800-page FBI files.[51] The investigation appears to have started when an anonymous informant reported overhearing Lomax's father telling guests in 1941 about what he considered his son's communist sympathies. Looking for leads, the FBI seized on the fact that, at the age of 17 in 1932 while attending Harvard for a year, Lomax had been arrested in Boston, Massachusetts, in connection with a political demonstration. In 1942 the FBI sent agents to interview students at Harvard's freshman dormitory about Lomax's participation in a demonstration that had occurred at Harvard ten years earlier in support of the immigration rights of one Edith Berkman, a Jewish woman, dubbed the "red flame" for her labor organizing activities among the textile workers of Lawrence, Massachusetts, and threatened with deportation as an alleged "Communist agitator".[52] Lomax had been charged with disturbing the peace and fined $25. Berkman, however, had been cleared of all accusations against her and was not deported. Nor had Lomax's Harvard academic record been affected in any way by his activities in her defense. Nevertheless, the bureau continued trying vainly to show that in 1932 Lomax had either distributed Communist literature or made public speeches in support of the Communist Party.

According to Ted Gioia:

Lomax must have felt it necessary to address the suspicions. He gave a sworn statement to an FBI agent on April 3, 1942, denying both of these charges. He also explained his arrest while at Harvard as the result of police overreaction. He was, he claimed, 15 at the time – he was actually 17 and a college student – and he said he had intended to participate in a peaceful demonstration. Lomax said he and his colleagues agreed to stop their protest when police asked them to, but that he was grabbed by a couple of policemen as he was walking away. "That is pretty much the story there, except that it distressed my father very, very much", Lomax told the FBI. "I had to defend my righteous position, and he couldn't understand me and I couldn't understand him. It has made a lot of unhappiness for the two of us because he loved Harvard and wanted me to be a great success there." Lomax transferred to the University of Texas the following year.[51]

Lomax left Harvard, after having spent his sophomore year there, to join John A. Lomax and John Lomax, Jr. in collecting folk songs for the Library of Congress and to assist his father in writing his books. In withdrawing him (in addition to not being able to afford the tuition), the elder Lomax had probably wanted to separate his son from new political associates that he considered undesirable. But Alan had also not been happy there and probably also wanted to be nearer his bereaved father and young sister, Bess, and to return to the close friends he had made during his first year at the University of Texas.

In June 1942 the FBI approached the Librarian of Congress, Archibald McLeish, in an attempt to have Lomax fired as Assistant in Charge of the Library's Archive of American Folk Song. At the time, Lomax was preparing for a field trip to the Mississippi Delta on behalf of the Library, where he would make landmark recordings of Muddy Waters, Son House, and David "Honeyboy" Edwards, among others. McLeish wrote to Hoover, defending Lomax: "I have studied the findings of these reports very carefully. I do not find positive evidence that Mr. Lomax has been engaged in subversive activities and I am therefore taking no disciplinary action toward him." Nevertheless, according to Gioia:

Yet what the probe failed to find in terms of prosecutable evidence, it made up for in speculation about his character. An FBI report dated July 23, 1943, describes Lomax as possessing "an erratic, artistic temperament" and a "bohemian attitude." It says: "He has a tendency to neglect his work over a period of time and then just before a deadline he produces excellent results." The file quotes one informant who said that "Lomax was a very peculiar individual, that he seemed to be very absent-minded and that he paid practically no attention to his personal appearance." This same source adds that he suspected Lomax's peculiarity and poor grooming habits came from associating with the "hillbillies who provided him with folk tunes.

Lomax, who was a founding member of People's Songs, was in charge of campaign music for Henry A. Wallace's 1948 Presidential run on the Progressive Party ticket on a platform opposing the arms race and supporting civil rights for Jews and African Americans. Subsequently, Lomax was one of the performers listed in the publication Red Channels as a possible Communist sympathizer and was consequently blacklisted from working in US entertainment industries.

A 2007 BBC news article revealed that in the early 1950s, the British MI5 placed Alan Lomax under surveillance as a suspected Communist. Its report concluded that although Lomax undoubtedly held "left wing" views, there was no evidence he was a Communist. Released September 4, 2007 (File ref KV 2/2701), a summary of his MI5 file reads as follows:

Noted American folk music archivist and collector Alan Lomax first attracted the attention of the Security Service when it was noted that he had made contact with the Romanian press attaché in London while he was working on a series of folk music broadcasts for the BBC in 1952. Correspondence ensued with the American authorities as to Lomax' suspected membership of the Communist Party, though no positive proof is found on this file. The Service took the view that Lomax' work compiling his collections of world folk music gave him a legitimate reason to contact the attaché, and that while his views (as demonstrated by his choice of songs and singers) were undoubtedly left wing, there was no need for any specific action against him.

The file contains a partial record of Lomax' movements, contacts and activities while in Britain, and includes for example a police report of the "Songs of the Iron Road" concert at St Pancras in December 1953. His association with [blacklisted American] film director Joseph Losey is also mentioned (serial 30a).[53]

The FBI again investigated Lomax in 1956 and sent a 68-page report to the CIA and the Attorney General's office. However, William Tompkins, assistant attorney general, wrote to Hoover that the investigation had failed to disclose sufficient evidence to warrant prosecution or the suspension of Lomax's passport.

Then, as late as 1979, an FBI report suggested that Lomax had recently impersonated an FBI agent. The report appears to have been based on mistaken identity. The person who reported the incident to the FBI said that the man in question was around 43, about 5 feet 9 inches and 190 pounds. The FBI file notes that Lomax stood 6 feet (1.8 m) tall, weighed 240 pounds and was 64 at the time:

Lomax resisted the FBI's attempts to interview him about the impersonation charges, but he finally met with agents at his home in November 1979. He denied that he'd been involved in the matter but did note that he'd been in New Hampshire in July 1979, visiting a film editor about a documentary. The FBI's report concluded that "Lomax made no secret of the fact that he disliked the FBI and disliked being interviewed by the FBI. Lomax was extremely nervous throughout the interview.[51]

The FBI investigation was concluded the following year, shortly after Lomax's 65th birthday.

Awards

Alan Lomax received the National Medal of Arts from President Ronald Reagan in 1986; a Library of Congress Living Legend Award[54] in 2000; and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Philosophy from Tulane University in 2001. He won the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award in 1993 for his book The Land Where the Blues Began, connecting the story of the origins of blues music with the prevalence of forced labor in the pre-World War II South (especially on the Mississippi levees). Lomax also received a posthumous Grammy Trustees Award for his lifetime achievements in 2003. Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax (Rounder Records, 8 CDs boxed set) won in two categories at the 48th annual Grammy Awards ceremony held on February 8, 2006[55] Alan Lomax in Haiti: Recordings For The Library Of Congress, 1936–1937, issued by Harte Records and made with the support and major funding from Kimberley Green and the Green foundation, and featuring 10 CDs of recorded music and film footage (shot by Elizabeth Lomax, then nineteen), a bound book of Lomax's selected letters and field journals, and notes by musicologist Gage Averill, was nominated for two Grammy Awards in 2011.[56]

World music and digital legacy

Brian Eno wrote of Lomax's later recording career in his notes to accompany an anthology of Lomax's world recordings:

[He later] turned his intelligent attentions to music from many other parts of the world, securing for them a dignity and status they had not previously been accorded. The "World Music" phenomenon arose partly from those efforts, as did his great book, Folk Song Style and Culture. I believe this is one of the most important books ever written about music, in my all time top ten. It is one of the very rare attempts to put cultural criticism onto a serious, comprehensible, and rational footing by someone who had the experience and breadth of vision to be able to do it.[57]

In January 2012, the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, with the Association for Cultural Equity, announced that they would release Lomax's vast archive in digital form. Lomax spent the last 20 years of his life working on an interactive multimedia educational computer project he called the Global Jukebox, which included 5,000 hours of sound recordings, 400,000 feet of film, 3,000 videotapes, and 5,000 photographs.[58] By February 2012, 17,000 music tracks from his archived collection were expected to be made available for free streaming, and later some of that music may be for sale as CDs or digital downloads.[59]

As of March 2012 this has been accomplished. Approximately 17,400 of Lomax's recordings from 1946 and later have been made available free online.[60][61] This is material from Alan Lomax's independent archive, begun in 1946, which has been digitized and offered by the Association for Cultural Equity. This is "distinct from the thousands of earlier recordings on acetate and aluminum discs he made from 1933 to 1942 under the auspices of the Library of Congress. This earlier collection – which includes the famous Jelly Roll Morton, Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, and Muddy Waters sessions, as well as Lomax's prodigious collections made in Haiti and Eastern Kentucky (1937) – is the provenance of the American Folklife Center"[60] at the library of Congress.

On August 24, 1997, at a concert at Wolf Trap, Vienna, Virginia, Bob Dylan had this to say about Lomax, who had helped introduce him to folk music and whom he had known as a young man in Greenwich Village:

There is a distinguished gentlemen here who came … I want to introduce him – named Alan Lomax. I don't know if many of you have heard of him [Audience applause.] Yes, he's here, he's made a trip out to see me. I used to know him years ago. I learned a lot there and Alan … Alan was one of those who unlocked the secrets of this kind of music. So if we've got anybody to thank, it's Alan. Thanks, Alan.[62]

In 1999 electronica musician Moby released his fifth album Play. It extensively used samples from field recordings collected by Lomax on the 1993 box set Sounds of the South: A Musical Journey from the Georgia Sea Islands to the Mississippi Delta.[63] The album went on to be certified platinum in more than 20 countries.[64]

Bibliography

A partial list of books by Alan Lomax includes:

- L'Anno piu' felice della mia vita (The Happiest Year of My Life), a book of ethnographic photos by Alan Lomax from his 1954–55 fieldwork in Italy, edited by Goffredo Plastino, preface by Martin Scorsese. Milano: Il Saggiatore, M2008.

- Alan Lomax: Mirades Miradas Glances. Photos by Alan Lomax, ed. by Antoni Pizà (Barcelona: Lunwerg / Fundacio Sa Nostra, 2006) ISBN 84-9785-271-0

- Alan Lomax: Selected Writings 1934–1997. Ronald D. Cohen, Editor (includes a chapter defining all the categories of cantometrics). New York: Routledge: 2003.

- Brown Girl in the Ring: An Anthology of Song Games from the Eastern Caribbean Compiler, with J. D. Elder and Bess Lomax Hawes. New York: Pantheon Books, 1997 (Cloth, ISBN 0-679-40453-8); New York: Random House, 1998 (Cloth).

- The Land Where The Blues Began. New York: Pantheon, 1993.

- Cantometrics: An Approach to the Anthropology of Music: Audiocassettes and a Handbook. Berkeley: University of California Media Extension Center, 1976.

- Folk Song Style and Culture. With contributions by Conrad Arensberg, Edwin E. Erickson, Victor Grauer, Norman Berkowitz, Irmgard Bartenieff, Forrestine Paulay, Joan Halifax, Barbara Ayres, Norman N. Markel, Roswell Rudd, Monika Vizedom, Fred Peng, Roger Wescott, David Brown. Washington, D.C.: Colonial Press Inc, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Publication no. 88, 1968.

- Penguin Book of American Folk Songs (1968)

- 3000 Years of Black Poetry. Alan Lomax and Raoul Abdul, Editors. New York: Dodd Mead Company, 1969. Paperback edition, Fawcett Publications, 1971.

- The Leadbelly Songbook. Moses Asch and Alan Lomax, Editors. Musical transcriptions by Jerry Silverman. Foreword by Moses Asch. New York: Oak Publications, 1962.

- Folk Songs of North America. Melodies and guitar chords transcribed by Peggy Seeger. New York: Doubleday, 1960.

- The Rainbow Sign. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1959.

- Leadbelly: A Collection of World Famous Songs by Huddie Ledbetter. Edited with John A. Lomax. Hally Wood, Music Editor. Special note on Lead Belly's 12-string guitar by Pete Seeger. New York: Folkways Music Publishers Company, 1959.

- Harriet and Her Harmonium: An American adventure with thirteen folk songs from the Lomax collection. Illustrated by Pearl Binder. Music arranged by Robert Gill. London: Faber and Faber, 1955.

- Mister Jelly Roll: The Fortunes of Jelly Roll Morton, New Orleans Creole and "Inventor of Jazz". Drawings by David Stone Martin. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1950.

- Folk Song: USA. With John A. Lomax. Piano accompaniment by Charles and Ruth Crawford Seeger. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, c.1947. Republished as Best Loved American Folk Songs, New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1947 (Cloth).

- Freedom Songs of the United Nations. With Svatava Jakobson. Washington, D.C.: Office of War Information, 1943.

- Our Singing Country: Folk Songs and Ballads. With John A. Lomax and Ruth Crawford Seeger. New York: MacMillan, 1941.

- Check-list of Recorded Songs in the English Language in the Archive of American Folk Song in July 1940. Washington, D.C.: Music Division, Library of Congress, 1942. Three volumes.

- American Folksong and Folklore: A Regional Bibliography. With Sidney Robertson Cowell. New York, Progressive Education Association, 1942. Reprint, Temecula, California: Reprint Services Corp., 1988 (62 pp. ISBN 0-7812-0767-3).

- Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly. With John A. Lomax. New York: Macmillan, 1936.

- American ballads and folk songs. With John Avery Lomax. Macmillan, 1934.

DVDs

- Lomax the Songhunter, documentary directed by Rogier Kappers, 2004 (issued on DVD 2007).

- American Patchwork television series, 1990 (five DVDs).

- Oss Oss Wee Oss 1951 (on a DVD with other films related to the Padstow May Day).

- Rhythms of Earth. Four films (Dance & Human History, Step Style, Palm Play, and The Longest Trail) made by Lomax (1974–1984) about his Choreometric cross-cultural analysis of dance and movement style. Two-and-a-half hours, plus one-and-a-half hours of interviews and 177 pages of text.

- The Land Where The Blues Began, expanded, thirtieth-anniversary edition of the 1979 documentary by Alan Lomax, filmmaker John Melville Bishop, and ethnomusicologist and civil rights activist Worth Long, with 3.5 hours of additional music and video.

- Ballads, Blues and Bluegrass, an Alan Lomax documentary released in 2012. His assistant Carla Rotolo was seen in the film.

See also

- Notable alumni of St. Mark's School of Texas

- Ian Brennan (music producer)

- Cantometrics

- The Singing Street

Footnotes

- "Alan Lomax Collection (The American Folklife Center, Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. May 15, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- During the New Deal called "applied folklore" or "functionalism" by Benjamin Botkin, see John Alexander Williams, "The Professionalization of Folklore Studies: a Comparative Perspective", Journal of the Folklore Institute 11: 3 (March 1975); 211–34.

- "Where the Songs Live". The Attic. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- "The American Folklife Center Celebrates Lomax Centennial". Loc.gov. January 15, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- "Alan Lomax Biography". Biography.com. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- John Szwed, Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World (New York: Viking, 2010), p. 20.

- Szwed (2010), p. 21.

- Szwed (2010), p. 22.

- Szwed (2010), p. 24.

- Szwed (2010), p. 92.

- Szwed (2010), p. 91.

- "Music Reviews". PopMatters. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- Gordon, Robert (2013). Can't be Satisfied: the life and times of Muddy Waters. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 9780857868695.

- Library of Congress. "Episode 4 Title: "Michigan‐I‐O"" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- Colin Scott and David Evans, liner Notes to Poor Man's Heaven (2003) CD in RCA Bluebird series When the Sun Goes Down, The Secret History of Rock and Roll, ASIN: B000092Q48. Midnight Special and Other Prison Songs was reissued complete on Bluebird in 2003.

- Szwed (2010), p. 163.

- Szwed (2010), p. 167.

- Alan put the blame on CBS president William Paley, who he claimed 'hated all that hillbilly music on his network'" (Szwed [2010], p. 167).

- Quoted in Ronald D. Cohen, The Rainbow Quest (University of Massachusetts Press, 2002), p. 25.

- Alan Lomax "Songs of the American Folk", Modern Music 18 (Jan.-Feb. 1941), quoted in Cohen (2002), p. 25.

- "After the Day of Infamy: 'Man-on-the-Street' Interviews Following the Attack on Pearl Harbor". Memory.loc.gov. December 8, 1941. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- Kaufman, Will (2017). Woody Guthrie's Modern World Blues. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-8061-5761-0.

- See Matthew Barton and Andrew L. Kaye, in Ronald D. Cohen (ed), Alan Lomax Selected Writings, (New York: Routledge, 2003), pp. 98–99.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved July 5, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Szwed, (2010), pp. 250–51.

- Congress passed the Act in Sept. 1950 over the veto of President Truman, who called the it "the greatest danger to freedom of speech, press, and assembly since the Alien and Sedition Laws of 1798," a "mockery of the Bill of Rights", and a "long step toward totalitarianism." See Harry S. Truman, "Veto of the Internal Security Bill" Archived March 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Harry S. Truman Library website

- Szwed (2010), p. 248.

- Szwed (2010) p. 251.

- Szwed (2010), p. 274.

- Szwed (2010), p. 275.

- "BBC Radio 4 – The First LP in Ireland". Bbc.co.uk. May 10, 2014. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- Gareth Huw Davies (April 7, 2013). "David Attenborough talks about his early years – making a music series". Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- "Alan Lomax & The Gaels". The Croft. February 6, 2010. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- McKean, Tom (November 2002). "The Gatherer of Songs". Leopard. Aberdeen, Scotland. Archived from the original on June 29, 2009. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- Quoted in Ronald D. Cohen's Rainbow Quest, University of Massachusetts Press, 2002, p. 140

- Rogers, Jude (March 21, 2008). "You want no sheen, just the song". The Guardian. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- Collins, Shirley, America Over The Water, SAF Publishing, 2004, pp.154–160

- Collins described her arrival in America 1959 in an interview with Johan Kugelberg:

Kugelberg: Lomax met you? Collins: He was on the dockside with Anne, his daughter. . . .. I think I arrived in April and I don't think we went south until August. It took quite a long time to get the money together; it kept falling through. I think Columbia was going to pay for it at one point, but they insisted he have a union engineer with him and someone extra like that—in situations we were going to be in would have been hopeless. So he refused, and they withdrew their funding. It was very last minute that the Ertegun brothers at Atlantic gave us the cash and we were gone within days of getting that money. Alan had wanted to do it earlier, but there was just no money to do it with. He had no money, ever. He was always living hand to mouth. Kugelberg: That's the nature of somebody who is making the path as he's going along. Also as a sidebar, considering who the Ertegun brothers were at that point in time, it's surprising to me that they greenlighted that project at that point in time. I love that series, I think it's one of the great series of albums ever. It's surprising that Atlantic Records made that leap of faith because the series is sort of outside of their paradigm. So, those months were spent in New York? Collins: We went to another place actually, we went to California, to the California Folk festival in Berkeley, this was sometime in the summer. And we stopped off in Chicago and stayed with Studs Terkel who was a hospitable man and his wonderful hospitable wife. Caught the train out to San Francisco from Chicago, which was an incredible experience. Sang at the Berkeley festival and met Jimmy Driftwood there for the first time. We all hit it off wonderfully. Kugelberg: Your friends in England were dying of envy. Collins: No, they didn't know.

(Kugelberg, Johan. "Shirley Collins interview, part 2 of 5". furious.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2011.) - Szwed (2010), p. 344.

- Carl Sagan, Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record (New York: Random House, 1978), pp. 204–205.

- Bulgarian singer Valya Balkanska, "Shepherdess Song" on YouTube

- Carl Sagan, Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record (New York: Random House, 1978), p. 16.

- Jon Pareles (July 20, 2002). "Alan Lomax, Who Raised Voice of Folk Music in U.S., Dies at 87". The New York Times. Retrieved February 28, 2008.

- "About Cultural Equity". culturalequity.org. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- [America Sings the Saga of America" (1947)]

- Ironically, perhaps, the phrase originated in an article Archived September 13, 2012, at Archive.today, later a best-selling 1943 book by Republican candidate Wendell Willkie.

- "National Endowment for the Arts, National Heritage Fellowships 2008". www.nea.gov. 2008. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- "About The Association for Cultural Equity | Association for Cultural Equity". The Association for Cultural Equity.

- "Lomax in Louisiana: Trials and Triumph". Louisianafolklife.org. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- On the vital connection between biological diversity and cultural diversity, see Maywa Montenegro and Terry Glavin, "Scientists Offer New Insight into What to Protect of the World's Rapidly Vanishing Languages, Cultures, and Species" in In Defense of Difference: Seed Magazine (Oct. 2008): "Last October, when United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) released its Global Outlook 4 report, reiterating the scientific consensus that, ultimately, humans are to blame for current global extinctions, UNEP for the first time made an explicit connection between the ongoing collapse of biological diversity and the rapid, global-scale withering of cultural and linguistic diversity: 'Global social and economic change is driving the loss of biodiversity and disrupting local ways of life by promoting cultural assimilation and homogenization,' the report noted. 'Cultural change, such as loss of cultural and spiritual values, languages, and traditional knowledge and practices, is a driver that can cause increasing pressures on biodiversity...In turn, these pressures impact human well-being'".

- Ted Gioia,"The Red-rumor blues", Los Angeles Times, April 23, 2006.

- See the Ann Burlak papers at the Archives of Smith College. Miss Berkman was defended by a lawyer from the International Labor Defense, the same organization that later defended the Scottsboro Boys. See "Edith Berkman Will Fight Deportation", Lewiston Daily Sun clip for July 29, 1931.

- Archived February 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "About the Library | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on July 8, 2008.

- Barton, Matt. "Jelly Roll Wins at Grammys (March 2006) – Library of Congress Information Bulletin". Loc.gov. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- "The Culture of Haiti Comes To Life". GRAMMY.com. January 25, 2010. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- Brian Eno, in liner notes to the Alan Lomax Collection Sampler (Rounder Records, 1997)

- "The Premiere of the Global Jukebox". Archived February 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Radio interview with Don Fleming by John Hockenberry on PRI's The Takeaway.

- Rohter, Larry (January 30, 2012). "Folklorist's Global Jukebox Goes Digital". The New York Times. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- "Research Center". Research.culturalequity.org. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- "Alan Lomax's Massive Archive Goes Online : The Record". NPR. March 28, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- Bob Dylan, quoted in Jeffrey Greenberg, liner notes to Alan Lomax: Popular Songbook, Rounder 82161-1863-2T, on website Album Liner Notes.com

- Weingarten, Christopher R. (July 2, 2009). ""Play" 10 Years Later: Moby's Track by Track Guide to 1999's Global Smash". Rolling Stone. New York. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 372. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

Further reading

- John Szwed. Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World . New York: Viking Press, 2010 (438 pp.: ISBN 978-0-670-02199-4) / London: William Heinemann, 2010 (438 pp.;ISBN 978-0-434-01232-9). Comprehensive biography.

- Barton, Matthew. "The Lomaxes", pp. 151–169, in Spenser, Scott B. The Ballad Collectors of North America: How Gathering Folksongs Transformed Academic Thought and American Identity (American Folk Music and Musicians Series). Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press. 2011. The American song collecting of John A. and Alan Lomax in historical perspective.

External links

- Nathan Salsburg, curator of the Alan Lomax Archive, on Lomax's "List of American Folk Songs On Commercial Recordings" (1940), Root Hog or Die, Sept 24, 2012. First methodological research into the pre-war commercial record companies' documentation of rural vernacular music. Nathan Salsburg writes: "Although compilers [Alan Lomax, Pete Seeger, and Bess Lomax Hawes] had little ... access to titles from the Gennett or OKeh catalogs ... it proved to be a highly influential road-map for at least two of the earliest and most influential collectors of this music: Harry Smith and James McKune."

- two-hour NPR streaming radio podcast, "The Sonic Journey of Alan Lomax: Recording America and the World", American Routes (March 13, 2013). Nick Spitzer, host. Follows the journey of Lomax in documenting the diversity of traditional music of America in the face of what he felt was the increased threat of the "monoculture" and as recordist, cultural theorist, radio host, and shaper of 20th-century pop culture through his discoveries. Features interviews with Lomax biographer John Szwed, daughter Anna Lomax Wood, nephew John Lomax III, folksinger Pete Seeger, and some past interviews of Alan Lomax himself.

- Alan Lomax Collection, The American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

- Association for Cultural Equity (ACE) – Alan Lomax pages

- "Remembrances of Alan Lomax, 2002" by Guy Carawan

- "Alan Lomax: Citizen Activist", by Ronald D. Cohen

- "Remembering Alan Lomax" by Bruce Jackson at the Wayback Machine (archived December 27, 2007)

- Interview of Shirley Collins reminiscing about Alan Lomax on Perfect Sound Forever.

- Alan Lomax films for viewing online – Appalachian Journey, Cajun Country, Dreams and Songs of the Noble Old, Jazz Parades: Feet Don't Fail Me Now, The Land Where the Blues Began.

- Lomax: the Songhunter from P.O.V. August 22, 2006. Discussion guide, streaming radio sampler, discussion board.

- Scene on YouTube taken from Lomax the songhunter, a musical documentary that travels the world to meet people whom Lomax recorded, and portrays his life through interviews with relatives.

- To Hear Your Banjo Play (1947), documentary film written by Alan Lomax, narrated by Pete Seeger, with Texas Gladden, Woody Guthrie, Baldwin Hawes, Cisco Houston, Brownie McGhee, Sonny Terry, and the Margot Mayo Square Dancers (The American Square Dance Group) on Google video

- Oss Oss Wee Oss by Alan Lomax and Peter Kennedy, a filmed documentary of the Padstow May Day Ceremony (1951) at Documentary Educational Resources.

- Adam Fisher, "Blues Travelers", T Magazine, The New York Times, May 17, 2012. Article about families of Otha Turner, exponent of African- influenced Colonial-style fife-and-drum playing, whom Alan Lomax recorded in 1942, 1959, and 1978, in Gravel Springs, northern Mississippi, and regarded as one of his greatest discoveries. Turner made his first CD at the age of 90, see Bill Ellis, "Fife Master, Rural Blues Legend Otha Turner dies; Was 94", Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), February 27, 2003. Turner's music was featured in Martin Scorsese's film Gangs of New York.

- Books by John A. and Alan Lomax

- Articles by Alan Lomax

- Alan Lomax discography

- Alan Lomax filmography

- Alan Lomax radio programs

- The V.D. Radio Project at The WNYC Archives

- Lomax and Lead Belly together Link