Lumad

The Lumad are a group of Austronesian indigenous people in the southern Philippines. It is a Cebuano term meaning "native" or "indigenous". The term is short for Katawhang Lumad (Literally: "indigenous people"), the autonym officially adopted by the delegates of the Lumad Mindanao Peoples Federation (LMPF) founding assembly on 26 June 1986 at the Guadalupe Formation Center, Balindog, Kidapawan, Cotabato, Philippines.[1] It is the self-ascription and collective identity of the indigenous peoples of Mindanao.

.jpg) Women in traditional Manobo attire during the Kaamulan Festival of Bukidnon | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Unknown | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

CARAGA Davao Region Northern Mindanao SOCCSKSARGEN Zamboanga Peninsula | |

| Languages | |

| Manobo languages, Chavacano (in Zamboanga region), Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Filipino, English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Roman Catholic, Protestant) and Animist | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Bajau people, Moro, Visayans, Filipinos, other Austronesian peoples |

| Demographics of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Filipinos |

.png)

History

The name Lumad grew out of the political awakening among tribes during the martial law regime of President Ferdinand Marcos. It was advocated and propagated by the members and affiliates of Lumad-Mindanao, a coalition of all-Lumad local and regional organizations which formalized themselves as such in June 1986 but started in 1983 as a multi-sectoral organization. Lumad-Mindanao’s main objective was to achieve self-determination for their member-tribes or, put more concretely, self-governance within their ancestral domain in accordance with their culture and customary laws. No other Lumad organization had the express goal in the past.[1]

Representatives from 15 tribes agreed in June 1986 to adopt the name; there were no delegates from the three major groups of the T'boli, the Teduray. The choice of a Cebuano word was a bit ironic but they deemed it appropriate as the Lumad tribes do not have any other common language except Cebuano. This marked the first time that these tribes had agreed to a common name for themselves, distinct from that of the Moros and different from the migrant majority and their descendants.

Ethnic groups

The Lumad are the un-Islamized and un-Christianized Austronesian peoples of Mindanao. They include groups like the Erumanen ne Menuvu', Matidsalug Manobo, Agusanon Manobo, Dulangan Manobo, Dabaw Manobo, Ata Manobo, B'laan, Kaulo, Banwaon, Bukidnon, Teduray, Lambangian, Higaunon, Dibabawon, Mangguwangan, Mansaka, Mandaya, K'lagan, Subanen, Tasaday, Tboli, Mamanuwa, Tagakaolo, Talaandig, Tagabawa, Ubu', Tinenanen, Kuwemanen, K'lata and Diyangan. Considered as "vulnerable groups", they live in hinterlands, forests, lowlands and coastal areas.[2]

The term lumad excludes the Butuanons and Surigaonons, even though these two groups are also native to Mindanao. This is due to their Visayan ethnicity and lack of close affinity with the Lumad. The Moros like the Maranao, Tausug, Sama-Bajau, Yakan, etc. are also excluded, despite being also native to Mindanao and despite some groups being closely related ethnolinguistically to the Lumad. This is because unlike the Lumad, the Moros converted to Islam during the 14th to 15th centuries. This can be confusing, since the word lumad literally means "native" in the Visayan languages.

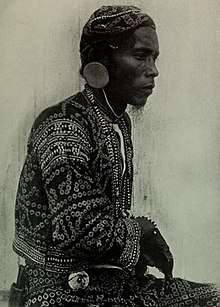

Bagobo

The Bagobo are one of the largest subgroups of the Manobo peoples. They comprise three subgroups: the Tagabawa, the Klata (or Guiangan), and the Ovu (also spelled Uvu or Ubo) peoples. The Bagobo were formerly nomadic and farmed through kaingin (slash-and-burn) methods. Their territory extends from the Davao Gulf to Mt. Apo. They are traditionally ruled by chieftains (matanum), a council of elders (magani), and female shamans (mabalian). The supreme spirit in their indigenous anito religions is Eugpamolak Manobo or Manama.[3][4][5]

Blaan

The Blaan is an indigenous group that is concentrated in Davao del Sur and South Cotabato. They practice indigenous rituals while adapting to the way of life of modern Filipinos.[6]

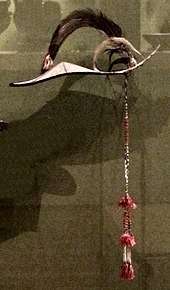

Bukidnon

.jpg)

The Bukidnon are one of the seven tribes in the Bukidnon plateau of Mindanao. Bukidnon means 'that of the mountains or highlands' (i.e., 'people of the mountains or highlands'), despite the fact that most Bukidnon tribes settle in the lowlands.

The name Bukidnon itself used to describe the entire province in a different context (it means 'mountainous lands' in this case) or could also be the collective name of the permanent residents in the province regardless of ethnicity.[7]

The Bukidnon people believe in one god, Magbabaya (Ruler of All), though there are several minor gods and goddesses that they worship as well. Religious rites are presided by a baylan whose ordination is voluntary and may come from any sex. The Bukidnons have rich musical and oral traditions[8] which are celebrated annually in Malaybalay city's Kaamulan Festival, with other tribes in Bukidnon (the Manobo tribes, the Higaonon, Matigsalug, Talaandig, Umayamnom, and the Tigwahanon).[9]

The Bukidnon Lumad is distinct from and should not be confused with the Visayan Suludnon people of Panay and a few indigenous peoples scattered in the Visayas area who are also alternatively referred to as "Bukidnon" (also meaning "highland people").

Higaonon

The Higaonon is located on the provinces of Bukidnon, Agusan del Sur, Misamis Oriental, Camiguin (used to be Kamiguing), Rogongon in Iligan City, and Lanao del Norte. The Higaonons have a rather traditional way of living. Farming is the most important economic activity.

The word Higaonon is derived from the word "Higad" in the Higaonon dialect which means coastal plains and "Gaon" meaning ascend to the mountains. Taken together, Higaonon, means the people of the coastal plains that ascended to the mountains. Higaonons were formerly coastal people of the provinces as mentioned who resisted the Spanish occupation. Driven to the hills and mountains these people continued to exist and fought for the preservation of the people, heritage and culture.

Kalagan

Also spelled "K'lagan" or (by the Spanish) "Caragan", is a subroup of the Mandaya-Mansaka people who speak the Kalagan language. They comprise three subgroups which are usually treated as different tribes: the Tagakaulo, the Kagan, and the Lao people. They are native to areas within Davao del Sur, Compostela Valley, Davao del Norte (including Samal Island), Davao Oriental, and North Cotabato; between the territories of the Blaan people and the coastline. The Caraga region is named after them. Their name means "spirited people" or "brave people", from kalag, ("spirit" or "soul"). They were historically composed of small warring groups. Their population, as of 1994, is 87,270.[10][11][12]

Kamigin

A subgroup of the Manobo people from the island of Camiguin. They speak the Kamigin language and are closely related to the Manobo groups from Surigao del Norte.[13]

Mamanwa

The Mamanwa is a Negrito tribe often grouped together with the Lumad. They come from Leyte, Agusan del Norte, and Surigao provinces in Mindanao; primarily in Kitcharao and Santiago, Agusan del Norte,[14] though they are lesser in number and more scattered and nomadic than the Manobos and Mandaya tribes who also inhabit the region. Like all Negritos, the Mamanwas are phenotypically distinct from the lowlanders and the upland living Manobos, exhibiting curly hair and much darker skin tones.

These peoples are traditionally hunter-gatherers[15] and consume a wide variety of wild plants, herbs, insects, and animals from tropical rainforest. The Mamanwa are categorized as having the "negrito" phenotype with dark skin, kinky hair, and short stature.[15][16] The origins of this phenotype (found in the Agta, Ati, and Aeta tribes in the Philippines) are a continued topic of debate, with recent evidence suggesting that the phenotype convergently evolved in several areas of southeast Asia.[17]

However, recent genomic evidence suggests that the Mamanwa were one of the first populations to leave Africa along with peoples in New Guinea and Australia, and that they diverged from a common origin about 36,000 years ago.[18]

Currently, Mamanwa populations live in sedentary settlements ("barangays") that are close to agricultural peoples and market centers. As a result, a substantial proportion of their diet includes starch-dense domesticated foods.[19] The extent to which agricultural products are bought or exchanged varies in each Mamanwa settlement with some individuals continuing to farm and produce their own domesticated foods while others rely on purchasing food from market centers. The Mamanwa have been exposed to many of the modernities mainstream agricultural populations possess and use such as cell phones, televisions, radio, processed foods, etc.[19]

The political system of the Mamanwa is informally democratic and age-structured. Elders are respected and are expected to maintain peace and order within the tribe. The chieftain, called a Tambayon, usually takes over the duties of counseling tribal members, speaking at gatherings, and arbitrating disagreements. The chieftain may be a man or a woman, which is characteristic of other gender-egalitarian hunter-gatherer societies.[20] They believe in a collection of spirits, which are governed by the supreme deity Magbabaya, although it appears that their contact with monotheist communities/populations has made a considerable impact on the Mamanwa's religious practices. The tribe produce excellent winnowing baskets, rattan hammocks, and other household containers.

Mamanwa (also spelled Mamanoa) means 'first forest dwellers', from the words man (first) and banwa (forest).[21] They speak the Mamanwa language (or Minamanwa).[22] They are genetically related to the Denisovans.[23]

Mandaya

"Mandaya" derives from "man" meaning "first," and "daya" meaning "upstream" or "upper portion of a river," and therefore means "the first people upstream". It refers to a number of groups found along the mountain ranges of Davao Oriental, as well as to their customs, language, and beliefs. The Mandaya are also found in Compostela and New Bataan in Compostela Valley (formerly a part of Davao del Norte Province).

Manobo

.jpg)

Manobo is the hispanicized spelling of the endonym Manuvu (also spelled Menuvu or Minuvu). Its etymology is unclear; in its current form it means 'person' or 'people'. It is believed that it is derived from the rootword tuvu which means "to grow"/"growth" (thus Man[t]uvu would be "[native]-grown" or "aboriginal").[24]

The Manobo are probably the most diverse ethnic groups of the Philippines in the relationships and names of the groups that belong to this family of languages. The total current Manobo population is not known, although they occupy core areas from Sarangani island into the Mindanao mainland in the regions of Agusan, Davao, Bukidnon, Surigao, Misamis, and Cotabato. A study by the journal NCCP-PACT put their population in 1988 at around 250,000. The groups occupy such a wide area of distribution that localized groups have assumed the character of distinctiveness as a separate ethnic grouping such as the Bagobo or the Higaonon, and the Atta. Depending on specific linguistic points of view, the membership of a dialect with a supergroup shifts.[25][26]

The Manobo possess Denisovan admixture, much like the Mamanwa.[23]

Mansaka

The term "Mansaka" derives from "man" with literal meaning "first" and "saka" meaning "to ascend," and means "the first people to ascend mountains/upstream." The term most likely describes the origin of these people who are found today in Davao del Norte and Davao del Sur. Specifically in the Batoto River, the Manat Valley, Caragan, Maragusan, the Hijo River Valley, and the seacoasts of Kingking, Maco, Kwambog, Hijo, Tagum, Libuganon, Tuganay, Ising, and Panabo.[27]

Matigsalug

Bukidnon groups who are found in the Tigwa-Salug Valley in San Fernando in Bukidnon province, Philippines. Their name means "people along the Salug River (now called the Davao River)". Although often classified under the Manobo ethnolinguistic group, the Matigsalug are a distinct sub-group.[28]

Sangil

The Sangil people (also called Sangir, Sangu, Marore, Sangirezen, or Talaoerezen) are originally from the Sangihe and Talaud Islands (now part of Indonesia) and parts of Davao Occidental (particularly in the Sarangani Islands), Davao del Norte, Davao del Sur, Sultan Kudarat, South Cotabato, and North Cotabato. Their populations (much like the Sama-Bajau) were separated when borders were drawn between the Philippines and Indonesia during the colonial era. The Sangil people are traditionally animistic, much like other Lumad peoples. During the colonial era, the Sangil (who usually call themselves "Sangir") in the Sangihe Islands mostly converted to Protestant Christianity due to proximity and contact with the Christian Minahasa people of Sulawesi. In the Philippines, most Sangil converted to Islam due to the influence of the neighboring Sultanate of Maguindanao. However, elements of animistic rituals still remain. The Indonesian and Filipino groups still maintain ties and both Manado Malay and Cebuano are spoken in both Indonesian Sangir and Filipino Sangil, in addition to the Sangirese language. The exact population of Sangil people in the Philippines is unknown, but is estimated to be around 10,000 people.[29][30][31][32]

Subanon

The Subanons are the first settlers of the Zamboanga peninsula. The family is patriarchal while the village is led by a chief called a Timuay. He acts as the village judge and is concerned with all communal matters.

History has better words to speak for Misamis Occidental. Its principal city was originally populated by the Subanon, a cultural group that once roamed the seas in great number; the province was an easy prey to the marauding sea pirates of Lanao whose habit was to stage lightning forays along the coastal areas in search of slaves. As the Subanon retreated deeper and deeper into the interior, the coastal areas became home to inhabitants from Bukidnon who were steadily followed by settlers from nearby Cebu and Bohol.

Tagabawa

Tagabawa is the language used by the Bagobo-Tagabawa. They are an indigenous tribe in Mindanao. They live in the surrounding areas of Mt. Apo.[33]

Tagakaulo

Tagakaulo is one of the tribes in Mindanao. Their traditional territories is in Davao Del Sur and the Sarangani Province particularly in the localities of Malalag, Lais, Talaguton Rivers, Sta. Maria, and Malita of Davao Occidental, and Malungon of the Sarangani Province. Tagakaulo means living in mountain. The Tagakaulo tribe originally came from the western shores of the gulf of Davao and south of Mt. Apo.[34] a long time ago.

Talaandig

Talaandig are originally from the foothills of Mount Kitanglad in Bukidnon, specifically in the municipalities of Talakag and Lantapan.[35]

Tasaday

The Tasaday is a group of about two dozen people living within the deep and mountainous rainforests of Mindanao, who attracted wide media attention in 1971 when they were first "discovered" by western scientists who reported that they were living at a "stone age" level of technology and had been completely isolated from the rest of Philippine society. They later attracted attention in the 1980s when it was reported that their discovery had in fact been an elaborate hoax, and doubt was raised both about their status as isolated from other societies and even about the reality of their existence as a separate ethnic group. The question of whether Tasaday studies published in the seventies are accurate is still being discussed.[36][37]

Teduray

The Teduray/Tiruray people live in the municipalities of Datu Blah T. Sinsuat, Upi, and South Upi in southwestern Maguindanao Province; and in Lebak municipality, northwestern Sultan Kudarat Province. They speak the Tiruray language, which is related to Bagobo, B'laan, and T'boli. Coastal Tirurays are mostly farmers, hunters, fishermen, and basket weavers; those living in the mountains engage in dry field agriculture, supplemented by hunting and the gathering of forest products. Tirurays are famous for their craftsmanship in weaving baskets with two-toned geometric designs. While many have adopted the cultures of neighboring Muslims and Christians people, a high percentage of their population still believe and practice their indigenous customs and rituals.[38]

Tboli

The Tboli are one of the indigenous peoples of South Mindanao. From the body of ethnographic and linguistic literature on Mindanao, they are variously known as Tboli, Teboli, Tau Bilil, Tau Bulul or Tagabilil. They term themselves Tboli. Their whereabouts and identity are to some extent confused in the literature; some publications present the Teboli and the Tagabilil as distinct peoples; some locate the Tbolis to the vicinity of the Buluan Lake in the Cotabato Basin or in Agusan del Norte. The Tbolis, then, reside on the mountain slopes on either side of the upper Alah Valley and the coastal area of Maitum, Maasim and Kiamba. In former times, the Tbolis also inhabited the upper Alah Valley floor.

Tigwahonon

The Tigwahonon are a subgroup of Manobo originally from the Tigwa River basin near San Fernando, Bukidnon.[39]

Umayamnon

The Umayamnon are originally from the Umayam River watershed and the headwaters of the Pulangi River. They are a subgroup of the Manobo.[40][41]

Languages

The Lumad peoples speak Philippine languages belonging to various branches. These include:

Musical heritage

Most of the Mindanao Lumad groups have a musical heritage consisting of various types of Agung ensembles – ensembles composed of large hanging, suspended or held, bossed/knobbed gongs which act as drone without any accompanying melodic instrument.[42]

Social issues

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Lumad controlled an area which now covers 17 of Mindanao’s 24 provinces, but by the 1980 census, they constituted less than 6% of the population of Mindanao and Sulu. Significant migration to Mindanao of Visayans, spurred by government-sponsored resettlement programmes, turned the Lumad into minorities. The Bukidnon province population grew from 63,470 in 1948 to 194,368 in 1960 and 414,762 in 1970, with the proportion of indigenous Bukidnons falling from 64% to 33% to 14%.

Lumad have a traditional concept of land ownership based on what their communities consider their ancestral territories. The historian B. R. Rodil notes that ‘a territory occupied by a community is a communal private property, and community members have the right of usufruct to any piece of unoccupied land within the communal territory.’ Ancestral lands include cultivated land as well as hunting grounds, rivers, forests, uncultivated land and the mineral resources below the land.

Unlike the Moros, the Lumad groups never formed a revolutionary group to unite them in armed struggle against the Philippine government. When the migrants came, many Lumad groups retreated into the mountains and forests. However, the Moro armed groups and the Communist-led New People’s Army (NPA) have recruited Lumad to their ranks, and the armed forces have also recruited them into paramilitary organisations to fight the Moros or the NPA.

For the Lumad, securing their rights to ancestral domain is as urgent as the Moros’ quest for self-determination. However, much of their land has already been registered in the name of multinational corporations, logging companies and other wealthy Filipinos, many of whom are, relatively speaking, recent settlers to Mindanao. Mai Tuan, a T'boli leader explains, "Now that there is a peace agreement for the MNLF, we are happy because we are given food assistance like rice … we also feel sad because we no longer have the pots to cook it with. We no longer have control over our ancestral lands."[43]

Lumad killings

The Lumad are people from various ethnic groups in Mindanao island. Residing in their ancestral lands,[44] they are often evicted and displaced because of the Moro people's claim on the same territory.[45] The Lumad have lost parts of their ancestral land because of a failure to understand the modern land tenure system.[46] Some NGOs have established schools in their communities, purportedly to supply essential knowledge for the tribe members that would protect their rights, property and culture.[47] However, the Lumad communities are located in mountains that are distant from urban areas. These areas are also the location sites of armed conflict between the New People's Army (NPA) and the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). Caught in the conflict, the Lumad people's education, property, and security are endangered because of the increasing amount of violent confrontations by the armed parties.[46] In Surigao del Sur, a barangay was evacuated to shelter sites in Tandag City because of increasing military and NPA activity.[48]

Manila-based activist groups claim that the Lumad territory were being militarized by the Armed Forces of the Philippines and that community leaders and teachers were being detained by the military on suspicion of being rebels.[49] They also say that alternative schools within the communities (aided by NGOs and universities) face concerns of closing down or demolition of their property, with some buildings converted by the military for their use.[50] They have staged demonstrations to gain the public's attention, calling for the halt of the alleged militarization of Lumad communities.[51] Groups like the Manilakbayan supported the movements through recruitment and the handing out of national situationers to students to spread awareness about the Lumad's dilemma.[52] The Philippines' Commission on Human Rights (CHR) has been investigating the incidents in regard to the 2015 murder of Lumad leaders and a school official by a paramilitary group called Magahat/Bagani[53] (in line with the idea of CAFGU) created by the AFP to hunt for NPA members. The AFP denies the allegation and attributes the killings to tribal conflict.[54] However, the AFP has admitted that CAFGU has Lumad recruits within its ranks while asserting that the NPA has also recruited Lumad for the group.[55][56] There is also delay of a decision on the CHR investigation because of the noncooperation of the Lumad group after the interruption of the investigation by the spokesman of Kalumaran Mindanao, Kerlan Fanagel. Fanagel insists that the group need not have another 'false' dialogue with the CHR since CHR has yet to present the results/findings of the investigations from the past months when Lumad leaders were killed. Because of the lack of data, CHR decided to postpone the presentation of their initial report to the second week of December 2015.[57]

In December 8, the Karapatan group asked the United Nations to probe the killings, after eight T'boli and Dulangan Manobo farmers were allegedly killed by members of the Philippine Army.[58][59]

However, these accusations were rebutted by some Lumad leaders who instead claim that it is the NPA who are responsible for the killings and that none of the alleged "militarization" is actually happening. Datu Malapandaw Nestor Apas of the Langilan Manobo people in Davao del Norte said, "There are no armed government forces in the community. The NPA rebels are the ones occupying our area to control indigenous peoples and seize ancestral lands."[60][61] They also accuse protesters in Manila of pretending to be Lumad by wearing Lumad clothing, denying that the Lumad participating in rallies in Manila were members of Lumad tribes.[62] They have also held anti-NPA rallies in Mindanao.[63] There have also been several assassinations on Lumad leaders sympathetic to the government blamed on NPA members.[64] Some of which are acknowledged by NPA members.[65][66]

In 2018, Duterte threatened to shut down or destroy NGO-funded community schools because of suspicions that they radicalize Lumad students into joining the NPA communist rebels.[67][68] This was supported by some Lumad leaders, who also felt that they were being infiltrated by the NPA and their children being exploited.[69][70][71]

In August 9, Lumad evacuees in Surigao del Sur formally returned to their homes after days to months in evacuation camps.[72]

See also

- Ethnic groups in the Philippines

- Indigenous peoples of the Philippines

- Manobo languages

- Filipino people

- Davaoeño people

- Moro people

- Sama-Bajau peoples

- Tagalog people

- Kapampangan people

- Ilocano people

- Ivatan people

- Igorot people

- Pangasinan people

- Bicolano people

- Negrito

- Visayan people

- Moro people

References

- Rodil, Rudy B. "The Tri-People Relationship and the Peace Process in Mindanao". Archived from the original on 5 August 2004. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- 31 October 2006, Kidapawan City, Philippines. Contributed by Pependayan, LMPF Secretary General from 1988–1999

- Mangune, Sonia D. "Bagobo". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- de Jong, Ronald (4 March 2010). "The last tribes of Mindanao, the Bagobo, the New People". ThingsAsian. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Carillo, Carmencita A. (13 October 2016). "Beauty queens from Bagobo tribe promote culture with coffee enterprise". BusinessWorld. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- B’laan women record dreams in woven mats – INQUIRER.net, Philippine News for Filipinos Archived 4 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Bukidnon". Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- Bukidnon heritage kept alive, Dr. Antonio Montalvan II Archived 25 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine", inq7.net (accessed through seasite.niu.edu on 3 February 2010)

- Kaamulan Festival Archived 10 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine", Bukidnon.gov (accessed 3 February 2010)

- "CARAGA Region History and Geography". National Nutrition Council. Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "It's Kagan, not Kalagan, new city ordinance says". SunStar Philippines. 20 January 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Peoples of the Philippines: Kalagan". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Amazing History about Camiguin Island". Bintana sa Paraiso. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Anthropology Museum: Mamanwa". California State University, East Bay. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Omoto K. 1989. Genetic studies of human populations in Asian-Pacific area with special reference to the origins of the Negritos. In: Hhba H, Hayami I, Michizuki K, orgs. Current Aspects of Biogeography in West Pacific and East Asian Regions. The University Museum, The University of Tokyo, Nature and Culture: 1.

- Barrows, David P. (1910). "The Negrito and allied types in the Philippines". American Anthropologist. 12 (3): 358–376. doi:10.1525/aa.1910.12.3.02a00020. JSTOR 659895.

- The HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium (2009). "Mapping Human Genetic Diversity in Asia". Science. 326 (5959): 1541–1545. doi:10.1126/science.1177074. PMID 20007900.

- Pugach, Irina; Delfin, Frederick; Gunnarsdóttir, Ellen; et al. (2013). "Genome-wide data substantiates Holocene gene ?ow from India to Australia". PNAS. 110 (5): 1803–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211927110. PMC 3562786. PMID 23319617.

- https://ucsc.academia.edu/EmeraldSnow/Papers/187939/Life-history_reproductive_maturity_and_the_evolution_of_small_body_size_The_Mamanwa_negritos_of_northern_Mindanao%5B%5D

- Cashdan, Elizabeth A. (1980). "Egalitarianism among Hunters and Gatherers". American Anthropologist. 82 (1): 116–120. doi:10.1525/aa.1980.82.1.02a00100.

- "Agusan-Surigao Historical Archive". Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- "Mamanwa". Ethnologue. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- Reich, David; Patterson, Nick; Kircher, Martin; et al. (2011). "Denisova admixture and the first modern human dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 89 (4): 516–528. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.005. PMC 3188841. PMID 21944045.

- Sevilla, Ester Orlida (1979). A Study of the Structure and Style of Two Manuvu Epic Songs in English Translation. University of San Carlos. p. 13.

- "Binantazan nga Banwa / Binantajan nu Bubungan, Philippines". ICCA Registry. UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Felix, Leny E. (2004). "Exploring the Indigenous Local Governance of Manobo Tribes in Mindanao" (PDF). Philippine Journal of Public Administration. 48XLVIII (1 & 2): 124–154.

- Fuentes, Vilma May A.; De La Cruz, Edito T. (1980). A Treasure of Mandaya and Mansaka Folk Literature. Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers. p. 2.

- "Matigsalug". Official Website of the Province of Bukidnon. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "Peoples of the Philippines: Sangil (Sangir/Marore)". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- "Population by Region and Religion - Kepulauan Sangihe Regency". sp2010.bps.go.id. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Hayase, Shinzō (2007). Mindanao Ethnohistory Beyond Nations: Maguindanao, Sangir, and Bagobo Societies in East Maritime Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-97-155-0511-6.

- Basa, Mick (9 March 2014). "The Indonesian Sangirs in Mindanao". Rappler. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- http://www.joshuaproject.net/people-profile.php?rop3=109689&rog3=RP Joshua Project – Bagobo, Tagabawa of Philippines Ethnic Profile

- "Tagakaolo". Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- "Talaandigs". Official Website of the Province of Bukidnon. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- Yengoyan, Aram A. (1991). "Shaping and Reshaping the Tasaday: A Question of Cultural Identity—A Review Article". The Journal of Asian Studies. 50 (3): 565–573. doi:10.2307/2057561.S\

- Hemley, Robin (2007). Invented Eden: The Elusive, Disputed History of the Tasaday. University of Nebraska Press.

- "Tiruray". Ethnic Groups of the Philippines.

- "Tigwahanon". Official Website of the Province of Bukidnon. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "Manobo, Umayamnon in Philippines". The Unknown. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "Umayamnon". Official Website of the Province of Bukidnon. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- Mercurio, Philip Dominguez (2006). "Traditional Music of the Southern Philippines". PnoyAndTheCity: A center for Kulintang – A home for Pasikings. Retrieved 25 February 2006.

- Mindanao, Land of Promise Archived 28 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Acosta, J. R. Nereus O. (1994). Loss, emergence, and retribalization: The politics of Lumad ethnicity in Northern Mindanao (Philippines) (Ph.D. thesis). University of Hawaii at Manoa. hdl:10125/15249.. Web. 5 November 2015.

- Paredes, Oona (2015). "Indigenous vs. native: negotiating the place of Lumads in the Bangsamoro homeland". Asian Ethnicity. 16 (2): 166–185. doi:10.1080/14631369.2015.1003690.

- FIANZA, MYRTHENA L. "Contesting Land and Identity In The Periphery: The Moro Indigenous People of Southern Philippines." https://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu. PSI-SDLAP, n.d. Web. 5 November 2015.

- Pangandoy: The Manobo Fight for Land, Education and Their Future. Dir. Hiyasmin Saturay. Perf. Manobo, Talaingod Manobo. Salugpongan Ta' Tanu Igkanogon, 2015. Documentary.

- Labrador, Kriztja Marae G. "Shelter Sites for Lumads Congested." Www.sunstar.com.ph. Sunstar Davao, 10 December 2014. Web. 6 November 2015.

- Cruz, Tonyo. "#StopLumadKillings: What You Need to Know." Tonyocruz.com. N.p., 4 September 2015. Web. 5 November 2015.

- Reyes, Rex R.B., Jr. "ON THE MILITARIZATON AND IMPENDING CLOSURE OF LUMAD SCHOOLS IN MINDANAO." NCCP. National Council of Churches in the Philippines, 5 June 2014. Web. 5 November 2015.

- PULUMBARIT, VERONICA. "Italian priest the third from PIME murdered in Mindanao? gmanetwork.com. GMA NEWS, 17 October 2011. Web. 05, November 2015

- Mateo, Janvic. "Lumads Demand End to Violence." Philstar.com. Philstar, 27 October 2015. Web. 5 November 2015.

- Templa, Mae Fe. "STATEMENT: Attacks on Mindanao Lumad Schools and Communities Intensify as Aquino's Military Goes Berserk for Oplan Bayanihan." MindaNews STATEMENT Attacks on Mindanao Lumad Schools and Communities Intensify as Aquinos Military Goes Berserk for Oplan Bayanihan Comments. Minda News, 5 September 2015. Web. 5 November 2015.

- "NPA Created the Conflict in Lumad Tribes - Office of The Army Chief." Philippine Information Agency. Republic of the Philippines, 28 September 2015. Web. 5 November 2015.

- Romero, Alexis. "AFP Denies Forced Recruitment, Extrajudicial Killings of Lumads." Philstar.com. Philstar, 4 November 2015. Web. 5 November 2015.

- BOLINGET, WINDEL. "'Lumad' Killings Not the Result of Tribal Conflict." Inquirer Opinion Lumad Killings Not the Result of Tribal Conflict Comments. Inquirer, 28 September 2015. Web. 5 November 2015.

- Ramirez, Robertzon. "Lumads Refuse Dialogue with CHR." Philstar.com. The Philippine Star, 29 October 2015. Web. 6 November 2015.

- "Karapatan asks UN to probe Lumad killings in Mindanao". Philstar.com. 8 December 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- Leonen, Julius N. "Militant group seeks UN probe on Lumad killings". Inquirer.net. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- Romero, Alexis (15 September 2015). "Lumad leaders blame NPA for Mindanao killings". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Uson, Mocha. "NPA killing Lumads?". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Caliwan, Christopher Lloyd (17 October 2018). "Lumad leaders meet with PNP chief; deny joining NPA". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Crismundo, Mike (11 December 2018). "Lumads, tribal leaders hold anti-NPA rally". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Manos, Merlyn (9 February 2018). "Lumad leader killed by NPA in Surigao del Norte — military". GMA News Online. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Nawal, Allan; Magbanua, Williamor (10 April 2018). "NPA rebels admit killing 'lumad' leader". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Basa, Mick (14 February 2018). "NPA congratulates fighters for killing Lumad father, son". Rappler. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "IPs on Lumad killings: the war isn't ours, but why are we the ones suffering". News5. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- "Duterte threatens to bomb Lumad schools". ABS-CBN News.

- Colina, Antonio L., IV (4 December 2018). "Lumad group condemns CPP-NPA and release of Talaingod 18". MindaNews. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Gagalac, Ron (6 December 2018). "Some Lumad leaders call for Red-tagged schools' shutdown". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Andrade, Jeanette I. (7 December 2018). "'Lumad' leaders want schools shut". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Lumad evacuees go back home". The Philippine Star.