Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898

The Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 (61 & 62 Vict. c. 37) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that established a system of local government in Ireland similar to that already created for England, Wales and Scotland by legislation in 1888 and 1889. The Act effectively ended landlord control of local government in Ireland.[1][2][3]

.svg.png) | |

| Long title | An Act for amending the Law relating to Local Government in Ireland, and for other purposes connected therewith. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 61 & 62 Vict. c. 37 |

| Introduced by | Gerald Balfour |

| Territorial extent | Ireland |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 12 August 1898 |

Status: Repealed | |

Background

From the 1880s the issue of local government reform in Ireland was a major political issue, involving both Irish politicians and the major British political parties. Questions of constitutional reform, land ownership and nationalism all combined to complicate matters, as did splits in both the Liberal Party in 1886 and the Irish Parliamentary Party in 1891. Eventually, the Conservative government of Lord Salisbury found it politically expedient to introduce the measures in 1898.

The legislation was seen by the government as solving a number of problems: it softened demands for Home Rule from Nationalists, it eased the burden of agricultural rates on Unionist landlords, it created a more efficient poor law administration and it strengthened the Union by bringing English forms of local government to Ireland.[2][3]

The existing system and earlier attempts at reform

Counties and baronies

Each county and county corporate of Ireland was administered before the 1898 Act by a grand jury. These bodies were made up of major landowners appointed by the assizes judge of the county. As well as their original judicial functions the grand juries had taken on the maintenance of roads, bridges and asylums and the supervision of other public works. The grand jury made proposals for expenditure known as "presentments" which required the approval of the assizes judge. The money to pay for the presentments was raised by a "county cess" levied on landowners and occupiers in the county, a form of rate tax.[4] A second tier of administrative division below the county was the barony. A similar system operated at this level, with the justices of the area empowered to meet in baronial presentment sessions to raise a cess to fund minor works.[4]

By 1880 the members of the grand juries and baronial sessions were still overwhelmingly Unionist and Protestant, and therefore totally unrepresentative of the majority of the population of the areas they governed.[3] This was because they had represented and were chosen from the actual taxpayers since the Middle Ages, and retiring members were normally replaced by similar taxpayers from the same social class. The understanding was that larger taxpayers had a greater motive to see that the tax money was spent properly. The Representation of the People Act 1884 created a much larger electorate that had very different needs and inevitably wanted to elect local representatives from outside a narrow social élite. By now public works such as roads and bridges were being funded increasingly by central government via the Office of Public Works.

Poor law unions and sanitary districts

In 1838 Ireland was divided into poor law unions (PLUs), each consisting of a geographical area based on a workhouse. The union boundaries did not correspond to those of any existing unit, and so many rurals lay in two or more counties. The unions were administered by Boards of Guardians. The boards were in part directly elected, with one guardian elected for each electoral division.

With the growth of population a need to create authorities to administer public health and provide or regulate such services as sewerage, paving and water supply arose. The Public Health (Ireland) Act 1878 created sanitary districts, based on the system already existing in England and Wales. Larger towns (municipal boroughs and towns with commissioners under private acts or with a population of 6,000 or more) were created urban sanitary districts: the existing local council became the urban sanitary authority. The remainder of the country was divided into rural sanitary districts. These were identical in area to poor law unions (less any part in an urban sanitary district), and the rural sanitary authority consisted of the poor law guardians for the area.

Proposed changes 1888–1892

The first proposals for elected County Councils in Ireland were made by the Radical-Liberal Minister Joseph Chamberlain to Prime Minister Gladstone in 1885.[5] The electorate had been enlarged by the recent Representation of the People Act 1884. However, Gladstone and Parnell preferred to legislate for Irish Home Rule first but failed to enact the 1886 Home Rule Bill. Chamberlain, briefly the President of the Local Government Board in 1886, then left the Liberals to form the Liberal Unionist Party and brought the proposal to his new Conservative allies, who won the 1886 United Kingdom general election shortly afterwards.

In 1888 Chamberlain again called for democratically-elected county councils in Ireland, as a part of a crash programme of state-funded public works, in his book "A Unionist Policy for Ireland".

Directly elected county councils were introduced to England and Wales by the Local Government Act 1888 and to Scotland by the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889. Attempts to bring about similar reforms in Ireland were delayed because of the civil unrest caused by the Plan of Campaign. The government argued that before they could bring in administrative reforms, law and order should be restored. Accordingly, the Chief Secretary, Arthur Balfour, introduced coercion acts to end the "agrarian outrages". Unionists, increasingly losing seats to members of the Irish National League at elections of guardians, also sought to delay implementation.[3][6]

Balfour finally announced on 10 August 1891 that local government legislation would be introduced in the next parliamentary session. The announcement was met with protests from Unionists and landlords who predicted that the new authorities would be disloyal and would monopolise their power to drive them out of the country. Balfour, despite the opposition, made it clear that he intended to proceed. With the Irish Parliamentary Party split into "Parnellite" and "anti-Parnellite" factions, he was encouraged to believe that the bill could be used to destroy the demand for Home Rule and further splinter the Nationalist movement.[3]

When the bill was introduced to parliament early in 1892, it was clear that the Unionists had successfully watered down many of its provisions by securing safeguards on their hold on local government. The provisions of the proposed legislation were:

- County and district councils, elected on the parliamentary franchise

- Transfer of powers of grand juries over roads and sanitation to the new councils

- Administration of local revenues and setting of county cess to be decided by the majority of ratepayers

The "safeguards" to protect the Unionist minority were:

- Electors to have "cumulative votes" with those paying more cess having more votes

- Any ratepayer could challenge the council presentment before a judge and jury

- County and district councils could be dismissed for "disobedience to the law, corruption or consistent malversion and oppression"

- A joint committee of councillors and grand jurors was to approve all capital expenditure and appointment of officers.[3]

The bill was rejected by almost all Irish parliamentarians, with the support of only a handful of Ulster Liberal Unionists. While Balfour hoped to make the legislation acceptable by tabling amendments, this was rejected by Nationalists who hoped to see a change to a pro-Home Rule Liberal administration at the imminent general election. The bill was accordingly abandoned.[3]

Gerald Balfour as Chief Secretary and the crisis of 1897

Following three years of Liberal government, a Conservative–Liberal Unionist government was returned to power at the 1895 general election. Gerald Balfour, brother of Arthur, and nephew of the new Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, was appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland on 4 July 1895. He soon made his mark when he clumsily summarised the Irish policy of the new government as "killing home rule with kindness".[2] The British Government passed three major pieces of Irish legislation in four years: apart from the Local Government Act, these were the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1896 and the Agriculture and Technical Instruction (Ireland) Act 1899.

The local government legislation was not originally part of the government's programme announced in the Queen's Speech of January 1897. It was also exceptional in that there was almost no popular demand for the reforms. It thus came as a complete surprise when Chief Secretary Balfour announced in May that he was preparing legislation. While he claimed that the extension to Ireland of the local government reforms already carried out in Great Britain had always been intended, the sudden conversion to the "alternative policy" was in fact a way of solving a political crisis at Westminster. Obstruction by Irish members of parliament and a number of English MPs was causing a legislative backlog. Landlords, already angered by the 1896 land act, were enraged by the refusal of the Treasury to extend the agricultural rating grant to Ireland. In fact, the failure to introduce the grant was largely due to there being no effective local government system to administer it. Instead, an equivalent sum had been given to the administration in Dublin Castle, who had decided to use the money to fund poor law reform and a new Agricultural Board. On 18 May the Irish Unionist MPs wrote to the government informing them that they would withdraw their support unless the rating grant was introduced.[2]

The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Cadogan, held talks with the Treasury and hit upon the idea of introducing the local government reforms as a way to "break up a combination of unionists with nationalists in Ireland" which he felt was "becoming too strong for even for a ministry with a majority of 150!" The introduction of democratic county councils along with a substantial rates subsidy was felt to be sure to placate all Irish members of the house.[2] The government moved quickly, sending a copy of the English Local Government Act of 1888 to Sir Henry Robinson, vice-president of the Local Government Board for Ireland. Robinson, who was on holiday, was instructed to decide how much of the existing legislation could be speedily adapted for Irish use. Within a week came the announcement that a bill was to be prepared.[2] There would not be enough time in a single parliamentary session to debate all planned measures, so an omnibus power was granted to Lord Lieutenant to pass Orders in Council adapting previous acts to Ireland, including parts of the (English) Municipal Corporations Acts 1882 and 1893 and Local Government Acts 1888 and 1894, and the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889.[7] This use of secondary legislation rather than primary legislation was controversial, but Irish nationalists accepted it as the price of getting the bill passed.[8]

The reforms

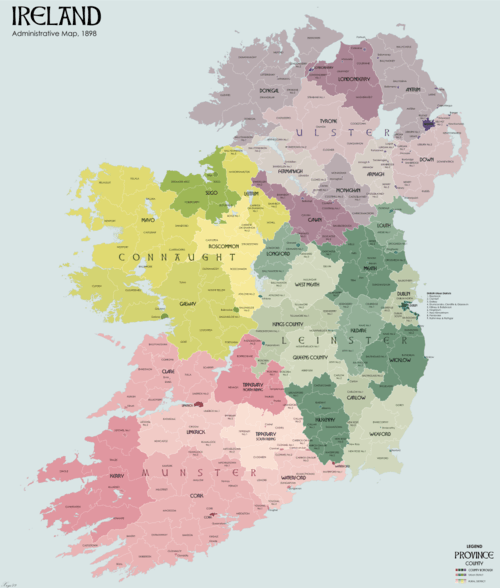

The 1898 Act brought in a mixed system of government, with County Boroughs independent of county administration, and elsewhere a two-tier system with county councils, along with Borough, Urban District and Rural District Councils. Urban districts were created from the larger of the town commissioners towns, while the smaller towns retained their town commissioners, but remained in the rural districts for sanitary planning purposes.

The creation of the new councils had a significant effect on Ireland as it allowed a much larger number of local people to take decisions affecting themselves. The county and the sub-county District Councils created a political platform for proponents of Irish Home Rule, displacing Unionist influence in many areas. The enfranchisement of local electors allowed the development of a new political class, creating a significant body of experienced politicians who would enter national politics in Ireland in the 1920s, and increase the stability of the transitions to the parliaments of the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland.

County and county borough boundaries

The Act caused a number of county boundaries to be modified. This was for several reasons:[9]

- Each county district had to be in a single county, unlike the sanitary districts on which they were based

- Where an urban sanitary district lay in more than one county, the new urban district would be placed entirely within that in which the majority of the population lay.

- Where a poor law union (PLU) lay in more than one county, generally a rural district was created for the fraction each county (for example, Ballyshannon PLU was split into Ballyshannon No.1, No.2, and No.3 rural districts in counties Donegal, Fermanagh, and Leitrim respectively). Boundaries were adjusted if one fraction was too small or otherwise impractical.

- The eight old counties corporate did not correspond to the six new county boroughs.

- The cities of Belfast and Derry were separated from the counties in which they lay and constituted as separate county boroughs.

- Four counties corporate were merged into their parent counties.

The extents of the new administrative counties and county boroughs, which came into effect on 18 April 1899, were defined by orders of the Local Government Board for Ireland.[10] There were no changes to the boundaries of the counties of Cavan, Cork, Donegal, Fermanagh, Kerry, Kildare, King's (Offaly), Leitrim, Limerick, Longford, Meath, Monaghan, and Tyrone; nor to those of the county boroughs (previously counties corporate) of Cork, Dublin, Limerick, and Waterford.[10] Changes elsewhere were as follows:[10]

| Pre-1898 judicial county | Post-1898 administrative county | Area transferred | Type of transfer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antrim | Belfast county borough | Belfast city (part) | New county borough |

| Carrickfergus (county of the town) | Antrim | All | Abolished corporate county |

| Down | Antrim | Lisburn town (part) | urban |

| Down | Armagh | Newry town (part) | urban |

| Down | Belfast county borough | Belfast city (part) | New county borough |

| Drogheda (county of the town) | Louth | All | Abolished corporate county |

| Dublin | Wicklow | Bray township (part) | urban |

| Galway | Clare | Drummaan, Inishcaltra North and Mountshannon EDs[t 1] | rural |

| Galway | Mayo | Ballinchalla, Owenbrin EDs[t 2] | rural |

| Galway | Roscommon | Rosmoylan ED | rural |

| Galway (county of the town) | Galway | All | Abolished corporate county |

| Kilkenny | Wexford | New Ross town (part) | urban |

| Kilkenny (county of the city) | Kilkenny | All | Abolished corporate county |

| Queen's (Laois) | Carlow | Carlow town (part) | urban |

| Londonderry | Londonderry (Derry)[t 3] county borough | Londonderry (Derry) city | New county borough |

| Mayo | Roscommon | Ballaghaderreen, Edmondstown EDs | rural |

| Roscommon | Galway | Ballinasloe town (part) | urban |

| Roscommon | Westmeath | Athlone town (part) | urban |

| Sligo | Mayo | Ardnaree North, Ardnaree South Rural, Ardnaree South Urban EDs[t 4] | rural |

| Tipperary, North Riding | Tipperary, South Riding | Cappagh, Curraheen, Glengar EDs | rural |

| Tipperary, South Riding | Waterford | Carrick-on-Suir town (part) Clonmel borough (part) | urban |

| Waterford | Kilkenny | Kilculliheen ED | rural |

- Notes

- This area is on the north-western shore of Lough Derg.

- These areas lay on the western shore of Lough Mask, and were remote from the rest of Galway.

- See Derry/Londonderry name dispute

- These areas were adjacent to the Mayo town of Ballina.

Main changes and repeals

Boundaries of Irish county constituencies at Westminster were not adjusted by the 1898 act to align with the new administrative boundaries. Some were aligned by the Representation of the People Act 1918, where the county divisions were being altered for other reasons; for example Kilculliheen was transferred from Waterford City to South Kilkenny, but Ardnaree remained in North Sligo rather than East Mayo.[11]

In 1919 the electoral system was changed to single transferable vote (STV) by the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1919. This was first used in the election to Sligo Corporation in 1919,[12] and then for the 1920 Irish local elections.[13] After the partition of Ireland in 1920–22, the situation evolved differently in the Irish Free State (Ireland from 1937) and Northern Ireland.

In the Free State, rural district councils were abolished by the Local Government Act 1925[14] (the Local Government (Dublin) Act 1930 for County Dublin[15]). Urban districts were renamed "towns" by the Local Government Act 2001, and abolished by the Local Government Reform Act 2014, which established municipal districts covering rural and urban areas of most counties. The 2001 act also renamed "county borough corporations" as "city councils". The introduction of a council–manager system in 1929–40 significantly changed the operation of county and city councils.

In Northern Ireland, STV was abolished in 1922.[16] The two-tier county–district system was retained until the Local Government Act (Northern Ireland) 1972 replaced it with a system of 26 unitary districts from 1973. Some elected councils had been dissolved in the 1960s as tensions grew in the buildup to the Troubles.

See also

Sources

References

Sources

- Primary

- Local Government Board for Ireland (1900). Twenty-seventh report. Command papers. C.9480. Dublin: Alex. Thom for HMSO. §§1–7 and Appendices A. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Irish Statute Book:

- "Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898". 2nd revised edition of the statutes. 1909.

- "British Public Statutes Affected: 1898". Pre-1922 Acts amendments. 19 January 2017. Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- "Local Government (Application of Enactments) Order, 1898". Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- "Local Government (Adaptation of Irish Enactments) Order, 1899". Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Secondary

- Clancy, John Joseph (1899). A handbook of local government in Ireland; containing an explanatory introduction to the Local Government (Ireland) Act, 1898 : together with the text of the act, the orders in Council, and the rules made thereunder relating to county council, rural district council, and guardian's elections : with an index. Dublin: Sealy, Bryers and Walker. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Gailey, Andrew (May 1984). "Unionist Rhetoric and Irish Local Government Reform, 1895–9". Irish Historic Studies. 24 (93): 52–68. JSTOR 30008026.

- Robinson, Henry Augustus (1923). "Local Government Reform (1898)". Memories: wise and otherwise. London. pp. 124–136. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

Citations

- Beckett, J C (1966). The Making of Modern Ireland 1603 – 1923. London: Faber & Faber. p. 406. ISBN 0-571-09267-5.

- Gailey 1984

- Shannon, Catherine B (March 1973). "The Ulster Liberal Unionists and Local Government Reform, 1885–98". Irish Historic Studies. 18 (71): 407–423. JSTOR 30005423.

- Roche, Desmond (1982). Local Government in Ireland. Dublin: Institute of Public Administration.

- Howard CHD Joseph Chamberlain, Parnell and the Irish "Central Board"; Irish Historical Studies, vol. 8, pp 32–61.

- Dunbabin, J P D (October 1977). "British Local Government Reform: The Nineteenth Century and after". The English Historical Review. 92 (365): 777–805. doi:10.1093/ehr/xcii.ccclxv.777. JSTOR 567654.

- Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, s.104 and Fourth Schedule; Local Government (Application of Enactments) Order 1898

- Robinson 1923 p.126

- "Proposed Alterations in Counties". The Irish Times. 19 July 1898. p. 7.

- "Orders declaring the boundaries of administrative counties and defining county electoral divisions". 27th Report of the Local Government Board for Ireland (Cmd.9480). Dublin: HMSO. 1900. pp. 235–330.

- Boundary Commission (Ireland); Lowther, 1st Viscount Ullswater, James William; Robinson, H. A.; Jerred, Walter T. (1917). Representation of the People Bill 1917 : Redistribution of seats: Report. Command papers. Cd.8830. HMSO. 6 "Procedure" and Schedule 6, Map. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ""P.R." At Sligo. A Municipal Experiment". The Times. 18 January 1919. p. 10.

- "Irish Election Results. "P.R." Working Smoothly". The Times. 17 January 1920. p. 12.

- "Local Government Act, 1925, Section 3". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- "Local Government (Dublin) Act, 1930, Section 82". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- Lynn, Brendan. "Introduction to the Electoral System in Northern Ireland". Politics: Elections. Conflict Archive on the Internet. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

The occasion also marked the re-introduction of PR-STV, which had been abolished for local government elections by the Northern Ireland government in 1922

External links

- Local Government (Ireland) Bill index to Hansard debates