Royal Liverpool University Hospital

The Royal Liverpool University Hospital (RLUH) is a major teaching and research hospital located in the city of Liverpool, England. It is the largest and busiest hospital in Merseyside and Cheshire, and has the largest emergency department of its kind in the UK.[1]

| Royal Liverpool University Hospital | |

|---|---|

| Liverpool University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | |

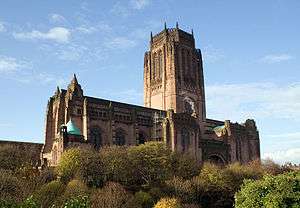

Main Entrance and Emergency Department at the existing Royal Liverpool University Hospital (completed in 1978) | |

| |

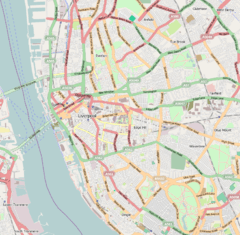

Location in Liverpool  Location in Merseyside | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Prescot Street, Liverpool, L7 8XP. |

| Coordinates | 53.40944°N 2.96412°W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | Public NHS |

| Type | Teaching |

| Affiliated university | University of Liverpool, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | Yes Accident & Emergency; Major Trauma Centre |

| Beds | 850 |

| Speciality | Organ Transplantation, Nephrology, Endocrinology, Ophthalmology, Vascular Surgery, Hepatology, Hepatobiliary Surgery, Orthopaedics, Oncology, Respiratory Medicine, Regional Tropical and Infectious Disease Unit. |

| History | |

| Opened | 1978 |

| Links | |

| Website | www |

A major redevelopment of the hospital began in 2013 and was scheduled for completion in 2017, but construction problems and the 2018 collapse of main contractor Carillion have pushed the estimated completion date back to 2022.

Alongside Broadgreen Hospital and Liverpool University Dental Hospital, the hospital is managed by the Liverpool University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and is associated with the University of Liverpool, Liverpool John Moores University and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

History

Current hospital

The current hospital, originally known simply as the Royal Liverpool Hospital, was designed to replace three other city centre acute hospitals that existed at the time – the Liverpool Royal Infirmary on Pembroke Place, the David Lewis Northern Hospital on Great Howard Street, and the Royal Southern Hospital on Caryl Street.[2] It had been agreed to amalgamate the separate facilities on a site in close proximity to the University of Liverpool for the purposes of medical education and research. The site on which the current hospital now stands (on Prescot Street) was identified as part of the post-war regeneration of Liverpool. However, building on the main hospital did not commence until 1963. The first phase of the hospital was designed by Holford Associates and built by Alfred McAlpine between 1963 and 1969.[3] The construction was plagued from the outset by problems of cost, time and quality, together with difficulties over fire certification due to changes in health and safety law whilst building work was ongoing. The second phase was completed and the hospital eventually opened in 1978.[4]

Redevelopment

In December 2013 the landmark £429 million redevelopment of the Royal Liverpool University Hospital, procured under a Private Finance Initiative contract, reached financial close; its collaborative links with the University of Liverpool, and institutes on the Liverpool BioCampus, have given the city of Liverpool recognition as one of the leading UK centres for health research and innovation.[5] The new Royal Liverpool University Hospital, which was designed by NBBJ and HKS[6] and was being built by Carillion, was expected to be the largest all single-patient room hospital in the UK upon its originally scheduled completion of March 2017.[7][8]

In March 2017, the project was running more than a year late due to problems caused by asbestos, cracking concrete and bad weather,[9] and further delays were announced in early January 2018.[10] Less than a fortnight later, on 15 January 2018, Carillion went into liquidation, partly due to its problems with the hospital contract, and delaying the project still further,[11][12] with the hospital unlikely to be finished in 2018.[13] On 26 March 2018, it was reported that the project had been costing £53.9m more than Carillion had officially reported.[14] In September, the NHS Trust revealed that the cost of rectifying serious faults, including replacing non-compliant cladding installed by Carillion, was holding up plans to restart and finish the £350m project; with the project further delayed, the Trust was considering invoking a break clause to terminate the PFI contract.[15] On 24 September 2018, it was reported that the government would step in to terminate the PFI deal, taking the hospital into full public ownership, meaning a £180m loss for private sector lenders Legal & General and the European Investment Bank.[16] This was confirmed on 26 September 2018, with completion of the hospital in 2020 likely to cost an additional £120m, due to unforeseen issues left behind by Carillion.[17]

Construction work was expected to resume in November 2018.[18] On 25 October 2018 Laing O'Rourke was confirmed as the contractor to complete the project,[19] but, a month later, with the contractor not prepared to take any risk, Mace was also appointed to help manage risks associated with the £350m scheme.[20] In April 2019, the project was reported to be facing further delays due to subcontractors' reluctance to work on the scheme,[21] while further defects were detected in May 2019, with rectification also likely to delay completion and increase costs.[22]

On 17 December 2019, hospital CEO Steve Warburton confirmed the project had been further delayed until at least 2022 and that patients and staff would be at the existing hospital for the next three winters.[23] In addition to £285m already spent, Warburton said completion would cost £300m, including costs to replace an aluminium composite cladding system, which, since the Grenfell Tower fire, was known to breach building regulations.[24] In March 2020, the hospital NHS Trust revealed it was drawing up claims against Carillion's insurers and a Carillion subcontractor Heyrod Construction.[25] In June 2020, the Portuguese manufacturer of the cladding was drafted in to remove it.[26]

A delayed National Audit Office report into the government's handling of the Royal Liverpool and Midland Metropolitan Hospitals was published in January 2020. The report warned of possible further significant cost increases, particularly to rectify the badly-built Liverpool project, and blamed Carillion for pricing the jobs too low to meet specifications. The two projects were expected to cost more than 40% more than their original budgets, and to be completed between three and five years late. However, due to effective risk transfer to the contractor, the total cost to the taxpayer would be very similar to the original plan.[27]

Part of the new hospital was opened early in May 2020 to provide additional critical care capacity during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom.[28]

Rating

In 2007, the Healthcare Commission rated Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust "Good" for 'Quality of Services' and Good for 'Use of Resources'.[29] In 2009, Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust was rated "Excellent" for the quality of its services and the quality of its financial management.[30]

Teaching and research

The Royal Liverpool University Hospital is a major teaching and research hospital for student doctors, nurses, dentists and allied health professionals. The hospital works with the University of Liverpool, Liverpool John Moores University and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.[31]

References

- "Royal Liverpool Hospitals". Rlbuht.nhs.uk. 23 May 2010. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- "Hospital Records". E. Chambré Hardman Archive. Archived from the original on 21 March 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- Gray, Tony (1987). The Road to Success: Alfred McAlpine 1935 - 1985. Rainbird Publishing. p. 107

- "Royal Liverpool Hospital". Hansard. 13 February 1980. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- Your Name Here. "About Us – Liverpool Health Campus". Liverpoolbiocampus.com. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- "NBBJ and HKS bag Royal Liverpool Hospital job". Architect's Journal. 2 May 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- "New £429m Royal Liverpool University Hospital given the green light – BBC News". BBC. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- "Royal Liverpool Hospital: New design unveiled – BBC News". BBC. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- Belger, Tom (31 March 2017). "Construction of new Royal hospital delayed again by a YEAR". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- Sembhy, Ravender; Houghton, Alistair (3 January 2018). "Here's why Royal Liverpool Hospital builder Carillion is in trouble - and why it matters". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- Matthews-King, Alex (16 January 2018). "Alarm in hospitals as NHS triggers emergency plans in 14 trusts after Carillion collapse". Independent. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Davies, Rob; Clark, Tim; Campbell, Denis (19 January 2018). "Carillion collapse further delays building at two major hospitals". Guardian. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- "Carillion collapse delays new £335m Liverpool hospital". BBC News. BBC. 6 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- Price, David (26 March 2018). "Carillion understated hospital costs by £70m". Construction News. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Morby, Aaron (12 September 2018). "Stalled Royal Liverpool Hospital fails cladding check". Construction Enquirer. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Kleinman, Mark (24 September 2018). "Ministers bail out £335m Liverpool hospital after Carillion collapse". Sky News. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- Brown, Faye (26 September 2018). "Royal Liverpool Hospital "to open in 2020" after PFI deal with Carillion ripped up". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- Prior, Grant (27 September 2018). "Construction to restart this year on Royal Liverpool Hospital". Construction Enquirer. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Garner-Purkis, Zak (26 October 2018). "Laing O'Rourke confirmed on Carillion's Royal Liverpool Hospital". Construction News. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Marshall, Jordan (26 November 2018). "Mace brought in to manage Carillion's Liverpool hospital as Laing O'Rourke restarts work". Building. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Marshall, Jordan (29 April 2019). "Wary subcontractors means timetable to restart stalled Carillion hospital slips". Building. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- Humphries, Jonathan (21 May 2019). "More 'defects' revealed in new Royal Hospital - prompting fears of further delays". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Royal Liverpool Hospital: Opening delayed again until at least 2022 - BBC News". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "Liverpool hospital completion delayed by two more years". The Construction Index. 19 December 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Weinfass, Ian (30 March 2020). "Liverpool hospital trust reveals subjects of potential legal action". Construction News. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Lowe, Tom (29 June 2020). "Faulty cladding on Carillion hospital to be removed by manufacturer". Building. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Morby, Aaron (17 January 2020). "NAO raises alarm over cost of finishing Carillion hospitals". Construction Enquirer. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Price, David (1 May 2020). "Royal Liverpool Hospital to partially open for COVID-19 care". Construction News. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- 2007 Rating

- 2009 Rating

- "Liverpool Health Campus". Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

External links