Ljudevit

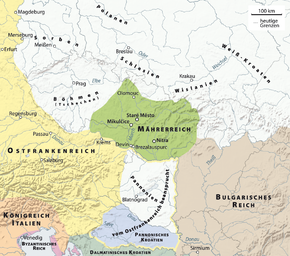

Ljudevit (pronounced [ʎûdeʋit]) or Liudewit (Latin: Liudewitus, often also Ljudevit Posavski), was the Duke of Pannonian Croatia[1] [b] from 810 to 823. The capital of his realm was in Sisak. As the ruler of the Pannonian Slavs,[2] he led a resistance to Frankish domination. Having lost the war against Franks, he fled to Ljudemisl, Borna's uncle, who treacherously killed him.[3]

| Ljudevit/Liudewit | |

|---|---|

| Duke of Pannonian Croatia[1][b] | |

| |

| Reign | c. 810 – c. 823 |

| Successor | Ratimir |

| Died | 823 Dalmatia |

Rebellions against the Franks

In 818 Ljudevit sent his emissaries to Emperor Louis in Heristal. They described the horrors conducted by Margrave Cadolah of Friuli (800-819) and his men in Pannonia, but the King of Franks refused to make peace. Ljudevit raised a rebellion against his Frankish rulers in 819 after he was seriously accused by the Frankish court.[4] The Emperor Louis the Pious (814-840) sent Cadolah to quell the rebellion. The Frankish Frontier forces led by Cadolah have raided the land and tortured the population, most notably the children. As the Pannonian Slavs were amassing forces, so did the Franks led by Cadolah return in 819. But the Frankish forces were soon defeated; and Cadolah himself had to retreat back to his home Friuli, where soon he died of disease.

In July 819 on the Council in Ingelheim Ljudevit's emissaries offered truce conditions, but Emperor Louis refused; demanding more concessions to him. Ljudevit started to gather allies for his plight. His original ally was Duke Borna (Dux Dalmatiae et Liburniae) - the leader of the Guduscani (Gačani), but the Frankish ruler had promised Borna that he would make him Prince of Pannonia if he helped the Franks to crush Ljudevit's rebellion; so Borna accepted. Ljudevit found assistance among the Carantanian and Carniolan Slavs who, as neighbours of the margravate of Friuli, were jeopardized the same as the Pannonians. The Timočani (living around the valley of Timok) also joined him, because they were jeopardized by the neighbouring Bulgars.

The Franks sent a large army led by the new Margrave of Friuli, duke Baldric of Friuli to meet Ljudevit in autumn, the same year while he was conscripting more Carantanian troops along the Drava river. The Frankish forces had numerical advantage, so they pushed Ljudevit and his men from Carniola across the Drava. Ljudevit had to fall back to central parts of his realm. Baldric didn't chase Ljudevit, since he had to pacify the Carantanians. Borna moved with Ljudevit's father-in-law Dragomuž and their forces from the south-west. At the heat of the Battle of Kupa, his own Guduscani abandoned Borna and crossed to Ljudevit's side; while Dragomuž was killed. Borna escaped from the battlefield with the help of his bodyguards.

Ljudevit seized the opportunity and breached into and raided Dalmatia in December. Borna was too weak, so the Dalmatians defended themselves through sneaky tactics and used attrition as their best ally to exhaust the Pannonian forces. Harsh winter came to the hill areas, forcing Ljudevit to retreat. According to Borna's reports to the Frankish Emperor, Ljudevit suffered heavy casualties: 3,000 soldiers, over 300 horses and lots of food.

War continues

In January of 820, Borna made an alliance with the Frankish Emperor in Aachen. The plan was to crush Ljudevit's realm with a joint-attack from three sides. As soon as the winter retreated, massive Frankish armies were being amassed in Italia, East Francia, Bavaria, Saxony and Alemannia that were going to simultaneously invade Ljudevit's lands in the spring. The northern Frankish group moved from Bavaria across Pannonia to make an invasion across the river of Drava. Ljudevit's forces successfully stopped this Army at the river. The southern group moved across the Noric Alps, using the road from Aquileia to Emona. Ljudevit was successful again, as he stopped them before crossing the Alps. The central group moved from Tyrol to Carniola. Ljudevit attempted to halt its advance three times, but every single time would the Franks win, using numerical advantage. When this Army reached the Drava, Ljudevit had to fall back to the heart of his realm.

The Franks have opened ways for the southern and northern Armies, so they launched a total invasion. Ljudevit concluded that all resistance would be futile, so he retreated to a stronghold that he built on top of hill that was heavily fortified; while his people took shelter in local forest and swamps. Ljudevit did not negotiate with the Franks. The Franks eventually retreated from his lands, with their ranks thinned by disease which the northern forces caught in the marshes of Drava. The Slavs from Carantania lost their internal independence and were forced to recognize the Friulian margrave Balderic as their ruler, while some remained loyal to Ljudevit. Prince Borna died in 821, and was succeeded by Ljudevit's nephew, Vladislav. Emperor Louis recognized as Prince of Dalmatia and Liburnia in February 821 at the Council of Aachen.

The Emperor discussed again about war plans against Ljudevit on that Council. The Franks decided to repeat the progress, and push towards Ljudevit from three sides again. Ljudevit saw that it was obvious that he couldn't fight the Franks on open field, so he began to construct massive fortifications. He was helped by the Venetian Patriarch Fortunat who sent him architects and masons from Italy.

During the last and final Frankish invasion of 822, the Patriarch from Grad, Fortunat, who was a supporter of Ljudevit, fled to Zadar into exile with the Byzantines.

Flight to Srb

According to Einhard, the writer of the Royal Frankish Annals, following the final Frankish attack, Ljudevit went from his seat in Sisak to Srb in 822 (Siscia civitate relicta, ad Sorabos, quae natio magnam Dalmatiae partem obtinere dicitur, fugiendo se contulit.).[5][6][5][6] Tadija Smičiklas did not attempt to define the area where Ljudevit fled, while Vjekoslav Klaić wrote it was beyond Sava and Bosna.[5] Ferdo Šišić put the ad Sorabos to the southeast of Sava and Vrbas, near the Dalmatian Croats. Vladimir Ćorović mentioned the flight to the Serbs, but didn't expound on it. The 1953 "History of the peoples of Yugoslavia" published by Školska knjiga added apparently fictitious details to the original story. Anto Babić discussed the original text and whether it was a reference to a single fort or a territory.[7] Svetislav M. Prvanović tried to connect Ljudevit and the Guduscani with the Roman city of Guduscum in eastern Serbia, but using only the interpretation of a single comma in Franjo Rački's text and conjecture. Sima Ćirković thought there was a consensus that the place was somewhere in Bosnia, but called the claims of exact locations speculation. Nada Klaić thought that the place Ljudevit fled to was actually the medieval county of Srb by the river Una.[8] Relja Novaković analyzed Einhard and concluded that the area could be somewhere near Kozara, Grmeč, Una and Kupa.[9] Ivo Goldstein acknowledged and accepted the theory that it was located in Srb, but advocated against misinterpreting the scarce historical records.[10] Radoslav Katičić argued against the theory, and Tibor Živković concurred with him.[11] Živković's 2011 interpretation of the Latin text says the second-hand accounts given to the Franks by their agents in Siscia and Croatia establish the existence of some sort of a Serbian claim over parts of (Roman) Dalmatia, similar to the analogous Frankish claim, but not necessarily settlement outside of places already known from other sources.[12]

Ljudevit soon sent an envoy to the Frankish court, claiming that he is ready to recognize the Frankish Emperor Louis the Pious as his supreme ruler. Then he fled to Ljudemisl, Borna's uncle, who treacherously killed him.[3]

Annotations

- ^ He was mentioned as "Liudewitus, dux Pannoniae inferioris" in the Frankish Annals.[13] This title is translated as "Duke of Lower Pannonia".[14] In older Croatian historiography, his title was claimed to have been "Duke of Pannonian Croatia", which is erraneous, as it is anachronistic. The Croat ethnonym was first mentioned in the late 9th century.[15]

References

- John Van Antwerp Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, 1991, p. 255

- Studia Slovenica. 3. Studia Slovenica. 1960. p. 21.

... in the unsuccessful rebellion of Ljudevit of Posavia (Ljudevit Posavski), leader of the Pannonic Slavs, against the Franks, the semi-independence of the land was definitely at an end. From 828 onward it was administered by Bavarian counts.

- Scholz 1970, p. 113.

- Škiljan, Filip (2008). Kulturno – historijski spomenici Banije s pregledom povijesti Banije od prapovijesti do 1881 [Cultural and historical monuments of Banija with an overview of history Banija from prehistory to 1881.] (in Serbian). Zagreb, Croatia: Serb National Council. ISBN 978-953-7442-04-0.

- Goldstein, 1985, p. 235.

- Curta 2006, pp. 136-137.

- Goldstein, 1985, p. 236.

- Goldstein, 1985, p. 237.

- Goldstein, 1985, p. 238.

- Goldstein, 1985, p. 243–244.

- Tibor Živković: On the Beginnings of Bosnia in the Middle Ages, 2010; in the Yearbook of the Center for Balkan Studies of the Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, p. 153, in Serbian,

- Živković 2011, pp. 392–396.

- Balcanoslavica. 5–7. 1977. p. 114.

The report refers to the uprising of Liudewitus, dux Pannoniae inferioris (Ljudevit Posavski), which was joined by the inhabitants of Carniola (Annales regni Francorum, ad a. 818 — 823).

- Oto Luthar (2008). The Land Between: A History of Slovenia. Peter Lang. pp. 109–. ISBN 978-3-631-57011-1.

- Gračanin, Hrvoje (June 2008). "Od Hrvata pak koji su stigli u Dalmaciju odvojio se jedan dio i zavladao Ilirikom i Panonijom: Razmatranja uz DAI c. 30, 75-78". History Teaching (in Croatian). Croatian Historical Society. VI (11 (1)). ISSN 1334-1375. Retrieved 2012-07-27.

Sources

- Royal Frankish Annales Annales Regni Francorum ed. G. H. Pertz. Monumenta Germanicae Historica, Scriptores rerum Germanicarum 6, (Hannover 1895) for the years 819-822.

- Scholz, Bernhard Walter, ed. (1970). Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories. University of Michigan Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Life of the Emperor Louis (Vita Hludowici), ed. E. Tremp. Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores rerum Germanicarum 64 (Hannover 1995) chapters 31-35.

- Moravcsik, Gyula, ed. (1967) [1949]. Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (2nd revised ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldstein, Ivo (May 1985). "Ponovno o Srbima u Hrvatskoj u 9. stoljeću" (PDF). Historijski zbornik (in Croatian). Savez povijesnih društava Hrvatske, Faculty of Philosophy, Zagreb. XXXVII (1). Retrieved 2012-07-27.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Živković, Tibor (2011). "The Origin of the Royal Frankish Annalist's Information about the Serbs in Dalmatia". Homage to Academician Sima Ćirković. Belgrade: The Institute for History. pp. 381–398.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)