Common linnet

The common linnet (Linaria cannabina) is a small passerine bird of the finch family, Fringillidae. It derives its scientific name from its fondness for hemp seeds and flax seeds—flax being the English name for the plant from which linen is made.

| Common linnet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male in breeding plumage in England | |

| |

| Female in Scotland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Fringillidae |

| Subfamily: | Carduelinae |

| Genus: | Linaria |

| Species: | L. cannabina |

| Binomial name | |

| Linaria cannabina | |

| |

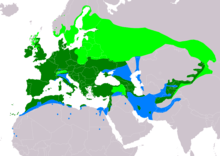

| Range of L. cannabina Breeding Resident Non-breeding | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

In 1758 the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus included the common linnet in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name, Acanthis cannabina.[2][3] The species was formerly placed in the genus Carduelis but based on the results of a phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences published in 2012, it was moved to the genus Linaria that had been introduced by the German naturalist Johann Matthäus Bechstein in 1802.[4][5][6]

The genus name linaria is the Latin for a linen-weaver, from linum, "flax". The species name cannabina comes from the Latin for hemp.[7] The English name has a similar root, being derived from Old French linette, from lin, "flax".[8]

There are seven recognised subspecies:[4]

- L. c. autochthona (Clancey, 1946) – Scotland

- L. c. cannabina (Linnaeus, 1758) – western, central and northern Europe, western and central Siberia. Non-breeding in north Africa and southwest Asia

- L. c. bella (Brehm, CL, 1845) – Middle East to Mongolia and northwestern China

- L. c. mediterranea (Tschusi, 1903) – Iberian Peninsula, Italy, Greece, northwest Africa and Mediterranean islands

- L. c. guentheri (Wolters, 1953) – Madeira

- L. c. meadewaldoi (Hartert, 1901) – western and central Canary Island (El Hierro and Gran Canaria)

- L. c. harterti (Bannerman, 1913) – eastern Canary Islands (Alegranza, Lanzarote and Fuerteventura)

_male.jpg) L. c. mediterranea, male

L. c. mediterranea, male_female.jpg) L. c. mediterranea, female

L. c. mediterranea, female_juvenile.jpg) L. c. mediterranea, juvenile

L. c. mediterranea, juvenile

Description

The common linnet is a slim bird with a long tail. The upper parts are brown, the throat is sullied white and the bill is grey. The summer male has a grey nape, red head-patch and red breast. Females and young birds lack the red and have white underparts, the breast streaked buff.

Distribution

The common linnet breeds in Europe, the western Palearctic and north Africa. It is partially resident, but many eastern and northern birds migrate farther south in the breeding range or move to the coasts. They are sometimes found several hundred miles off-shore.[9]

Behaviour

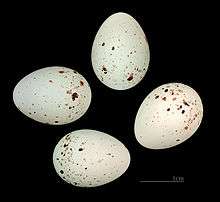

Open land with thick bushes is favoured for breeding, including heathland and garden. It builds its nest in a bush, laying four to seven eggs.

This species can form large flocks outside the breeding season, sometimes mixed with other finches, such as twite, on coasts and salt marshes.

The common linnet's pleasant song contains fast trills and twitters.

It feeds on the ground, and low down in bushes, its food mainly consisting of seeds, which it also feeds to its chicks. It likes small to medium-sized seeds from most arable weeds, knotgrass, dock), crucifers (including charlock, shepherd's purse), chickweeds, dandelions, thistle, sow-thistle, mayweed, common groundsel, common hawthorn and birch. They have a small component of Invertebrates in their diet.

Conservation

The common linnet is listed by the UK Biodiversity Action Plan as a priority species. It is protected in the UK by the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.

In Britain, populations are declining, attributed to increasing use of herbicides, aggressive scrub removal and excessive hedge trimming; its population fell by 56% between 1968 and 1991, probably due to a decrease in seed supply and the increasing use of herbicide. From 1980–2009, according to the Pan-European Common Bird Monitoring Scheme, the European population decreased by 62%[10]

Favourable management practices on agricultural land include:

- Set-aside

- Overwinter stubbles

- Uncultivated margins, ditches, field corners

- Conservation headlands

- Wild bird cover, using plants that produce small, oil-rich seeds, such as kale, quinoa, mustard plant and oil-seed rape Brassica napus

- Restoration of meadows: restoration and creation of hay-meadows

- Short, thick, thorny hedgerows and scrub for nesting habitat

Robert Burns's 1788 poem "A Mother's Lament for the Death of Her Son" also tells of a linnet bird bewailing her ravished young.

Cultural references

The bird was a popular pet in the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. Alfred, Lord Tennyson mentions "the linnet born within the cage" in Canto 27 of his 1849 poem "In Memoriam A.H.H.", the same section that contains the famous lines "'Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all." A "cock linnet" features in the classic British music hall song of that period My Old Man, and as a character in Oscar Wilde's children's story "The Devoted Friend"; Wilde also mentions how the call of the linnet awakens "The Selfish Giant" to the one tree where it is springtime in his garden. William Butler Yeats evokes the image of the common linnet in The Lake Isle of Innisfree (1890) in line 8: "And evening full of the linnet's wings." In the novel The Old Curiosity Shop by Charles Dickens, the heroine Nell keeps "only a poor linnet" in a cage, which she leaves for Kit as a sign of her gratefulness to him.

The English Baroque composer John Blow composed an ode on the occasion of the death of his colleague Henry Purcell, "An Ode on the Death of Mr. Purcell" set to the poem "Mark how the lark and linnet sing" by the poet John Dryden.

"The Linnets" has become the nickname of King's Lynn Football Club, Burscough Football Club and Runcorn Linnets Football Club (formerly known as 'Runcorn F.C.' and Runcorn F.C. Halton). Barry Town F.C., the South Wales-based football team, also used to be nicknamed 'The Linnets'.

William Blake invokes "the linnet's song" in one of the poems entitled "Song" in his Poetical Sketches.

Walter de la Mare's poem "The Linnet", published in 1918 in the collection Motley and Other Poems, has been set to music by a number of composers including Cecil Armstrong Gibbs, Kenneth Leighton[11] and Jack Gibbons.[12]

The Eurovision Song Contest 2014 entry for the Netherlands "The Common Linnets" is a direct reference to the bird.

William Wordsworth argued that the song of the common linnet provides more wisdom than books in the third verse of "The Tables Turned":

Books! 'tis a dull and endless strife:

Come, hear the woodland linnet,

How sweet his music! on my life,

There's more of wisdom in it.

But the fellow English poet Robert Bridges used the common linnet instead to express the limitations of poetry—concentrating on the difficulty in poetry of conveying the beauty of a bird's song. He wrote in the first verse:

I heard a linnet courting

His lady in the spring:

His mates were idly sporting,

Nor stayed to hear him sing

His song of love.—

I fear my speech distorting

His tender love.

The musical Sweeney Todd features the song "Green Finch and Linnet Bird", in which a young lady confined to her room wonders why caged birds sing:

Green finch and linnet bird,

Nightingale, blackbird,

How is it you sing?

How can you jubilate,

Sitting in cages,

Never taking wing?

In Emily Dickinson's poem "Morns like these—we parted—" the last line is: "And this linnet flew!"

Gallery

Young in nest

Young in nest

ID composite

ID composite

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Carduelis cannabina". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Paynter, Raymond A. Jnr., ed. (1968). Check-list of birds of the world, Volume 14. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 255–256.

- Linnaeus, C. (1766). Systema Naturæ per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis, Volume 1 (in Latin) (10th ed.). Holmiae:Laurentii Salvii. p. 182.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David (eds.). "Finches, euphonias". World Bird List Version 5.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Zuccon, Dario; Prŷs-Jones, Robert; Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Ericson, Per G.P. (2012). "The phylogenetic relationships and generic limits of finches (Fringillidae)" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 62 (2): 581–596. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.10.002. PMID 22023825.

- Bechstein, Johann Matthäus (1803). Ornithologisches Taschenbuch von und für Deutschland, oder, Kurze Beschreibung aller Vögel Deutschlands für Liebhaber dieses Theils der Naturgeschichte (in German). Leipzig: Carl Friedrich Enoch Richter. p. 121.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 89, 227. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- "Linnet". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- https://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/1/3/3/11330/11330-h/11330-h.htm

- http://www.birdlife.org/community/2011/08/farmland-birds-in-europe-fall-to-lowest-levels/

- "The LiederNet Archive". 2008-01-11. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- "Gibbons: 'The Linnet', Op.25". YouTube. 2010-12-06. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

Further reading

- Winspear, Richard; Davies, Gethin (2005). A Management Guide to Birds of Lowland Farmland. RSPB Management Guides. Sandy, Bedfordshire, UK: Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. ISBN 9781901930573. OCLC 954855935.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carduelis cannabina. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1921 Collier's Encyclopedia article Common linnet. |

- Common Linnet · Linaria cannabina · (Linnaeus, 1758)—Audio recordings from Xeno-canto

- Linnet (Carduelis cannabina) at Wildscreen's Arkive (videos, stills)

- BBC Wildlifefinder—Videos, sound files and information programmes featuring linnets

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 4.8 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze